The Campaign of 1814: Chapter 16, Part VI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906

Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906 Volker Sellin European Monarchies from 1814 to 1906 A Century of Restorations Originally published as Das Jahrhundert der Restaurationen, 1814 bis 1906, Munich: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2014. Translated by Volker Sellin An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-052177-1 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-052453-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-052209-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover Image: Louis-Philippe Crépin (1772–1851): Allégorie du retour des Bourbons le 24 avril 1814: Louis XVIII relevant la France de ses ruines. Musée national du Château de Versailles. bpk / RMN - Grand Palais / Christophe Fouin. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Contents Introduction 1 France1814 8 Poland 1815 26 Germany 1818 –1848 44 Spain 1834 63 Italy 1848 83 Russia 1906 102 Conclusion 122 Bibliography 126 Index 139 Introduction In 1989,the world commemorated the outbreak of the French Revolution two hundred years earlier.The event was celebratedasthe breakthrough of popular sovereignty and modernconstitutionalism. -

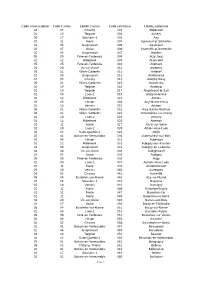

Classement Général 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 6 6 7 7 8 8 9 9 10 10 11

N° Classement Général Nom Prénom C.postal Ville Temps Dosssard Team chimay Cresson Julien 2500 Aubenton 01:36:45 28/04/2019 1 7 Team chimay Cauet Thibault 2140 Landouzy la ville 01:36:45 28/04/2019 1 LES RESISTANTS SINET Yannick 80132 NEUILLY L'HOPITAL 01:38:41 28/04/2019 2 5 LES RESISTANTS FLEURY Fabien 2840 ATHIES-SOUS-LAON 01:38:41 28/04/2019 2 Les Colombes COLOMBE SEBASTIEN 2350 BUCY LES PIERREPONT 01:40:25 28/04/2019 3 1 Les Colombes COLOMBE MATHILDE 2350 BUCY LES PIERREPONT 01:40:25 28/04/2019 3 La Vauxaillonnaise Culpin Sacha 2320 Vauxaillon 01:41:53 28/04/2019 4 8 La Vauxaillonnaise Serrisier Claire 2320 Vauxaillon 01:41:53 28/04/2019 4 Les pongistes delorme marc 2350 Missy les Pierrepont 01:54:28 28/04/2019 5 19 Les pongistes lebris benjamin 2350 Missy les Pierrepont 01:54:28 28/04/2019 5 Amicale pompiers duhant ludovic 2140 ROUGERIES 01:54:54 28/04/2019 6 2 Amicale pompiers Marecat Clémence 2390 Origny sainte benoite 01:54:54 28/04/2019 6 Les Petites Setup MARECHAL Antoine 2320 PINON 01:54:57 28/04/2019 7 13 Les Petites Setup ARRIGONI Nathan 2000 LAON 01:54:57 28/04/2019 7 Girly team CLEMENT CHRISTELLE 2000 Chambry 01:55:10 28/04/2019 8 25 Girly team DELACROIX NATACHA 2000 CLACY 01:55:10 28/04/2019 8 LES BRAS CASSES PIOT DAMIEN 2350 BUCY LES PIERREPONT 01:55:17 28/04/2019 9 10 LES BRAS CASSES FLEURY THIBAULT 2340 SOIZE 01:55:17 28/04/2019 9 FLG A Fond Les Grognons Delloux Jennifer 2860 Bouconville Vauclair 01:57:48 28/04/2019 10 4 FLG A Fond Les Grognons Nogas Frederic 2190 Neufchatel Sur Aisne 01:57:48 28/04/2019 10 Leguay -

RESULTATS MICROBES MONTCORNET 540 M NOM

RESULTATS MICROBES MONTCORNET 540 m NOM PRENOM CLUB TEMPS mn s 1 BEAUDON Benoit URCEL 2 35 2 BRANDELET Servane SISSONNE 2 36 3 BOCQUET Enguerrand MARC 2 51 4 VERCAUTEREN Clémence MARC 2 57 5 JACQUELET Bryan MARC 3 0 6 CLEMENCEAU Mathieu SISSONNE 3 1 7 GAUDERIN Tom CHAILLEVOIS 3 9 ENVOI RESULTATS MONTCORNET.xls 26/11/2007 RESULTATS DES COURSES mini poussins et mini poussines 500540 m Arrivée Nom_Premom clubinscrit_ce_jourDossart Temps 1 CLEMENCEAU Morgane SISSONNE O 1 2 mn 34 s 2 LORAIN Eugénie SISSONNE O 7 2 mn 40 s 3 BONTEMPS Apolline SISSONNE O 4 2 mn 42 s 4 TEIRLYNCK Thibault MONTCORNET O 17 2 mn 51 s 5 RAGI Océane CHAILLEVOIS O 20 2 mn 54 s 6 JACQUELET Dylan CUIRIEUX O 18 2 mn 56 s 7 GOEBEERT Anaïs SISSONNE O 3 2 mn 58 s 8 LESSAUX Morgane IND O 19 3 mn 3 s 9 BOCQUET Maeva CUIRIEUX O 16 3 mn 8 s 10 JACQUOT Lucy SISSONNE O 2 3 mn 10 s poussins et poussines 1260 m Arrivée Nom_Premom clubinscrit_ce_jourDossart Temps 1 VERCAUTEREN Antoine CUIRIEUX O 119 5 mn 4 s 2 WERY Valentin CHAILLEVOIS O 124 5 mn 17 s 3 LESAUX Thibault ind O 122 5 mn 34 s 4 GROSSOT Romain IND O 123 5 mn 50 s 5 BRANDELET Marie SISSONNE O 101 5 mn 55 s 6 ANCELLE Sébastien SISSONNE O 102 6 mn 10 s 7 PONS Florie SISSONNE O 103 6 mn 45 s 8 RENARD Julie CUIRIEUX O 121 7 mn 10 s 9 BISSEUX Léa SISSONNE O 104 7 mn 18 s 10 RAVAUX Marion IND O 125 7 mn 26 s benjamins 2230 m Arrivée Nom_Premom clubinscrit_ce_jourDossart Temps 1 CARLIER David IND O 213 9 mn 58 s 2 DEROISIER Maxence IND O 211 11 mn 2 s 3 VERCAUTEREN Thomas CUIRIEUX O 209 11 mn 27 s 4 CUVILLIER Mathieu CHAILLEVOIS -

CC 11/03/2020 Délibération 24

Copie pour impression Réception au contrôle de légalité le 11/03/2020 à 10h56 Réference de l'AR : 002-200071769-20200310-2020_024-DE Affiché le 11/03/2020 -EXTRAIT Certifié exécutoire DU REGISTRE le 11/03/2020 DES DELIBERATIONS De la Communauté de Communes Picardie des Châteaux L’an deux mille vingt, le mardi 10 mars à 18 heures 30, le conseil communautaire s’est réuni à Lizy, conformément à l’article 2122-17 du Code général des Collectivités Territoriales sur la convocation de Monsieur Vincent MORLET, Président, adressée aux délégués des communes le vendredi 6 mars 2020. Monsieur le Président ouvre la séance à 18 heures 30 minutes. Les délégués présents en séance ont signé la liste d’émargement. Présents : Anizy-le Grand Anizy-le-Grand Monsieur Ambroise CENTONZE-SANDRAS; Madame Patricia ARTUS, Barisis-aux-Bois Madame AZEVEDO Alcinda ; Monsieur Philippe LECLERE ; Monsieur Philippe Bassoles-Aulers Besmé CARLIER ; Monsieur Jean Pierre PASQUIER ; Blérancourt Barisis aux Bois Monsieur Emmanuel FONTAINE ; Bourguignon-sous-Coucy Bassoles-Aulers Madame Isabelle HERBULOT ; Bourguignon-sous-Montbavin Bourguignon-sous-Montbavin Monsieur Gérard FEUTRY; Brancourt-en-Laonnois Camelin Monsieur Francis BORGNE ; Camelin Chaillevois Monsieur Alain GELEE ; Chaillevois Coucy-le-Château Monsieur Jack DUMINIL; Champs Crécy-au-Mont Monsieur Vincent MORLET ; Coucy-la-Ville Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique Folembray Monsieur Pascal FORET ; Madame Monique ALEXANDRE ; Madame Crécy-au-Mont Franciane PETIT; Folembray Fresnes sous Coucy Monsieur Quentin GUILMONT ; Fresnes -

Volume 1 Number 1 2014

Volume 1 ♦ Number 1 ♦ 2014 The Undergraduate Historical Journal At University of California, Merced The Editorial Board (Spring Issue, 2014) Rocco Bowman, Chief Editor Peter Racco, Editor Sarah Spoljaric, Editor Aaron Lan, Editor Havilliah J. Malsbury, Editor Andrew O'Connor, Editor The Undergraduate Historical Journal is edited and managed by undergraduate history majors attending UC Merced. Publishing bi-annually, it is organized by The Historical Society at UC Merced and authorized by the School of Social Sciences, Humanities, and Arts. All correspondence should be directed to the editorial board: Email: [email protected] Cover design by Rocco Bowman Cover image: Illustration by Hermann Thiersch (1874 – 1939). [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lighthouse_- _Thiersch.gif] Published by California Digital Library All authors reserve rights to their respective articles published herein. Table of Contents Letter from the Editors 1 Letter from the Advisor 2 Dr. Ruth Mostern, Associate Professor of History Articles Implications of Mystic Intoxication in Chinese and Iranian Poetry 5 Rebecca Weston Barricades in Berlin: Social Unrest, Constitutionalism, and Revolt in 1848 11 Josh Teixeira The Rise of Kings and Emperors: Sundiata and World Leaders of the 13th 31 Century Havilliah J. Malsbury The Disguised Mask of Race, Gender, and Class 35 Genesis Diaz The Hardships of Slaves and Millworkers 41 Stephanie Gamboa Extraction of the American Native: How Westward Expansion Destroyed and 45 Created Societies Juan Pirir Japanese Internment: Struggle Within the Newspapers 49 Chul Wan Solomon Park From Spirit to Machine: American Expansion and the Dispossession of the 55 Native Americans Alan Kyle Chinatown: The Semi-Permeable Construction of Space and Time 59 Mario Pulido The Forgotten Soldiers: Mexican-American Soldiers of WWII and the Creation 65 of the G.I. -

9781469658254 WEB.Pdf

Literary Paternity, Literary Friendship From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Literary Paternity, Literary Friendship Essays in Honor of Stanley Corngold edited by gerhard richter UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 125 Copyright © 2002 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Richter, Gerhard. Literary Paternity, Liter- ary Friendship: Essays in Honor of Stanley Corngold. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9780807861417_Richter Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Richter, Gerhard, editor. Title: Literary paternity, literary friendship : essays in honor of Stanley Corngold / edited by Gerhard Richter. Other titles: University of North Carolina studies in the Germanic languages and literatures ; no. 125. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2002] Series: University of North Carolina studies in the Germanic languages and literatures | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 2001057825 | isbn 978-1-4696-5824-7 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5825-4 (ebook) Subjects: German literature — History and criticism. -

Recueil Des Actes Administratifs 2013 AVRIL 3 Intégral.Odt 1

Recueil des actes administratifs 2013_AVRIL_3_Intégral.odt 1 PREFECTURE DE L’AISNE RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS Édition partie 3 du mois d’AVRIL 2014 209 ème année 2014 Mensuel - Abonnement annuel : 31 euros Recueil des actes administratifs 2013_AVRIL_3_Intégral.odt 899 PREFECTURE CABINET Bureau de la sécurité intérieure Arrêté préfectoral en date du 30 avril 2014 relatif à la police des débits de boissons dans le Page 901 département de l’Aisne DIRECTION DES LIBERTÉS PUBLIQUES Bureau de la réglementation générale et des élections Arrêté de cessibilité en date du 24 avril 2014 relatif au projet de requalification du quartier du Page 908 faubourg d’Isle à SAINT-QUENTIN au titre du Programme National de Requalification des Quartiers Anciens Dégradés (PNRQAD) et son annexe. DIRECTION DÉPARTEMENTALE DES TERRITOIRES Service Habitat, Rénovation Urbaine, Construction Programme d'actions 2014 signé le 24 avril 2014 par Michel Gasser, Page 910 délégué adjoint de l'Agence nationale de l'habitat (Anah) dans le département Service Environnement – Unité Gestion de l’eau Arrêté préfectoral en date du 22 avril 2014 autorisant la pêche de la carpe à toute heure dans Page 956 l'étang communal dit de « Cavessy » à Blérancourt la nuit du samedi au dimanche au cours des mois de juin, juillet et août 2014 Arrêté préfectoral en date du 22 avril 2014 autorisant temporairement la pêche de la carpe à Page 956 toute heure dans l'étang communal de Fontaine-les-Vervins Arrêté préfectoral en date du 22 avril 2014 autorisant la pêche de la carpe à toute heure -

Code Circonscription Code Canton Libellé Canton Code Commune

Code circonscription Code Canton Libellé Canton Code commune Libellé_commune 04 03 Chauny 001 Abbécourt 01 18 Tergnier 002 Achery 05 17 Soissons-2 003 Acy 03 11 Marle 004 Agnicourt-et-Séchelles 01 06 Guignicourt 005 Aguilcourt 03 07 Guise 006 Aisonville-et-Bernoville 01 06 Guignicourt 007 Aizelles 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 008 Aizy-Jouy 02 12 Ribemont 009 Alaincourt 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 010 Allemant 04 20 Vic-sur-Aisne 011 Ambleny 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 012 Ambrief 01 06 Guignicourt 013 Amifontaine 04 03 Chauny 014 Amigny-Rouy 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 015 Ancienville 01 18 Tergnier 016 Andelain 01 18 Tergnier 017 Anguilcourt-le-Sart 01 09 Laon-1 018 Anizy-le-Grand 02 12 Ribemont 019 Annois 03 08 Hirson 020 Any-Martin-Rieux 01 19 Vervins 021 Archon 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 022 Arcy-Sainte-Restitue 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 023 Armentières-sur-Ourcq 01 10 Laon-2 024 Arrancy 02 12 Ribemont 025 Artemps 01 11 Marle 027 Assis-sur-Serre 01 10 Laon-2 028 Athies-sous-Laon 02 13 Saint-Quentin-1 029 Attilly 02 01 Bohain-en-Vermandois 030 Aubencheul-aux-Bois 03 08 Hirson 031 Aubenton 02 12 Ribemont 032 Aubigny-aux-Kaisnes 01 06 Guignicourt 033 Aubigny-en-Laonnois 04 20 Vic-sur-Aisne 034 Audignicourt 03 07 Guise 035 Audigny 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 036 Augy 01 09 Laon-1 037 Aulnois-sous-Laon 03 11 Marle 039 Autremencourt 03 19 Vervins 040 Autreppes 04 03 Chauny 041 Autreville 05 04 Essômes-sur-Marne 042 Azy-sur-Marne 04 16 Soissons-1 043 Bagneux 03 19 Vervins 044 Bancigny 01 11 Marle 046 Barenton-Bugny 01 11 Marle 047 Barenton-Cel 01 11 Marle 048 Barenton-sur-Serre -

Les Arts Et Les Lettres

Laonnois Balade à pied Durée : 4 h 00 LesLes arartsts etet lesles lettrlettreses Longueur : 13,5 km MERLIEUX-ET-FOUQUEROLLES – LIZY – BOURGUIGNON-SOUS-MONTBAVIN – MONTBAVIN – ROYAUCOURT- ▼ 87 m - ▲ 188 m ET-CHAILVET – CHAILLEVOIS – MERLIEUX-ET-FOUQUEROLLES. Balisage : jaune et bleu De Bourguignon à Merlieux, cette balade bucolique résume Niveau : difficile admirablement le patrimoine laonnois : les vendangeoirs et la maison natale des frères Le Nain, le château de Chailvet paré d’une façade Points forts : • Paysages des collines à l’italienne et les lavoirs qui enjolivent le circuit. du Laonnois. • Beaux villages Du petit parking au- Marcheurs à Royaucourt. remarquablement préservés. D dessus de la salle -S. Lefebvre- polyvalente de Merlieux. Revenir dans la rue princi- bois, partir à droite et chemin faisant : pale que l’on prend à faire de même 250 m droite. Face au n° 34, plus loin. 6 À l’intersec- • Vendangeoirs, lavoirs et fontaines monter à gauche le che- tion, descendre vers remarquables sur tout le parcours. min goudronné. Tourner Bourguignon par le che- • Site St-Fiacre (abreuvoirs, lavoirs et fontaines en cascade) à Montbavin. à gauche. Longer un pré min des Molières. 7 À • Village remarquable (site classé) et reprendre un sentier Bourguignon, prendre de Bourguignon-sous-Montbavin : au-dessus d’une haie. en face la rue des Ven- À découvrir hôtel de ville, château, anciens Virer et plonger à dangeoirs (fontaines, vendangeoirs des XVII-XVIIIe s. (dont celui des frères Le Nain, privé). gauche. 1 À Valavergny, vendangeoirs, château • Pignons à « pas de moineaux » suivre la rue de Lizy. À la privé, maison natale des à Bourguignon. -

Iii - Patrimoine Et Biodiversité 38

E tat I nitial de l’ E nvironnement – SCoT de la Communauté d'Agglomération du Pays de Laon 2 N o v e m b r e 2014 SOMMAIRE I – ENVIRONNEMENT PHYSIQUE 7 1.1 L’ENVIRONNEMENT GÉOLOGIQUE 7 1.2 L’ENVIRONNEMENT TOPOGRAPHIQUE 12 1.3 L’ENVIRONNEMENT HYDROGRAPHIQUE 14 1.3.1 Bassin versant de l’Ailette 14 1.3.2 Bassin versant de la Serre 15 1.3.3 Lac de l’Ailette 15 1.4 L’ENVIRONNEMENT CLIMATIQUE 17 1.4.1 Les températures 18 1.4.2 Les précipitations 18 1.4.3 L’ensoleillement 19 1.4.4 Les vents 19 II – PAYSAGES ET CADRE DE VIE 21 2.1 LES MODES D’OCCUPATION DES SOLS (MOS) 21 2.1.1 Répartition des MOS 21 2.1.2 Les caractéristiques de l’occupation des sols 24 2.2 LES UNITÉS PAYSAGÈRES 29 2.2.1 La plaine du Laonnois 30 2.2.2 Les Collines du Laonnois 32 2.2.3 Le Massif de Saint-Gobain 34 E tat I nitial de l’ E nvironnement – SCoT de la Communauté d'Agglomération du Pays de Laon 3 N o v e m b r e 2014 2.3 LES ENJEUX PAYSAGERS 37 III - PATRIMOINE ET BIODIVERSITÉ 38 3.1 LE PATRIMOINE NATUREL REMARQUABLE 38 3.1.1 Les espaces recensés – ZNIEFF et ZICO 38 3.1.1.1 ZNIEFF de type II ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 38 3.1.1.2 ZNIEFF de type I ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 41 3.1.1.3 Zone importante pour la conservation des oiseaux - ZICO ________________________________________________________________________ 42 3.1.2. -

Laon Et Son Pays

LAON ET SON PAYS ARTS DU CIRQUE avec les compagnies Isis et La Folle Allure Les artistes circassiens vous donnent rendez-vous dans plusieurs sites au fil d’un parcours autour de la cathédrale et du quartier canonial, pour des moments de poésie en résonance avec les vieilles © DR pierres. LA ROUE (Isis) - Parvis de la cathédrale samedi, 14h30 MUR DE PIERRE (La Folle Allure) - Cloître de la cathédrale samedi, 14h45 et 17h15 LES TRÉTEAUX (Isis) - Cloître de la cathédrale samedi, 15h et 17h CORDE LISSE (La Folle Allure) - Jardin du musée samedi, 15h30 et 16h30 FUNAMBULISME SUR CORDE (Isis) - Jardin du musée samedi, 15h45 et 16h15 CORDE LESTÉE (La Folle Allure) - Jardin du musée samedi, 16h Tissu aérien avec la Compagnie Isis Cloître de l’abbaye Saint-Martin (bibliothèque Suzanne-Martinet) samedi, 15h10, 16h10 et 17h10 Musée d’art et d’archéologie du Pays de Laon (jardin) dimanche, 15h, 16h et 17h Démonstrations circassiennes avec la Compagnie Isis Cloître de l’abbaye Saint-Martin (bibliothèque Suzanne-Martinet) dimanche, 14h45 et 16h45 ORPHÉE ET EURYDICE Spectacle et atelier par la Compagnie Le Théâtre des Ombres Mêlant avec poésie, ombres chinoises et chants, ce spectacle plonge le public au cœur de la mythologie grecque dans l’incroyable histoire d’Orphée où apparaissent la belle Eurydice, les animaux sauvages ou encore de terrifiantes créatures. © DR SPECTACLES & CONCERTS À LAON Maison des Associations (9 rue du bourg), salle du rez-de-chaussée et salle de la mosaïque samedi, représentations à 14h, 14h30, 15h, 16h30 et 17h30 - atelier à 15h30 dimanche, représentations à 11h, 14h30, 15h, 16h30 et à 17h - ateliers à 11h30 et 15h30. -

DIG Renaturation De L'ardon

1 Identification du demandeur 2 Présentation du maître d’ouvrage 3 Localisation de la zone de travaux 4 Description des travaux prévus 5 Contexte réglementaire et rubriques concernées 6 Description du milieu physique 7 Description environnementale 8 Document d’incidences 9 Délibération du maître d’ouvrage 10 Lexique 11 Annexes 1 1. Identification du demandeur .................................................................... 7 Maitre d’ouvrage ..................................................................................................... 7 Assistance à maîtrise d’Ouvrage .............................................................................. 7 2. Présentation du maître d’ouvrage ............................................................ 9 Le bassin versant de l’Ardon et de l’Ailette ............................................................. 9 Création du syndicat ................................................................................................ 9 Compétences ......................................................................................................... 10 Zone géographique d’intervention ........................................................................ 10 Travaux entrepris à ce jour .................................................................................... 11 L’équipe de techniciens ......................................................................................... 12 3. Localisation de la zone de travaux ........................................................... 14 4.