Scf.70414 Broderick, G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manx Traditional Dance Revival 1929 to 1960

‘…while the others did some capers’: the Manx Traditional Dance revival 1929 to 1960 By kind permission of Manx National Heritage Cinzia Curtis 2006 This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Arts in Manx Studies, Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool. September 2006. The following would not have been possible without the help and support of all of the staff at the Centre for Manx Studies. Special thanks must be extended to the staff at the Manx National Library and Archive for their patience and help with accessing the relevant resources and particularly for permission to use many of the images included in this dissertation. Thanks also go to Claire Corkill, Sue Jaques and David Collister for tolerating my constant verbalised thought processes! ‘…while the others did some capers’: The Manx Traditional Dance Revival 1929 to 1960 Preliminary Information 0.1 List of Abbreviations 0.2 A Note on referencing 0.3 Names of dances 0.4 List of Illustrations Chapter 1: Introduction 1.1 Methodology 1 1.2 Dancing on the Isle of Man in the 19th Century 5 Chapter 2: The Collection 2.1 Mona Douglas 11 2.2 Philip Leighton Stowell 15 2.3 The Collection of Manx Dances 17 Chapter 3: The Demonstration 3.1 1929 EFDS Vacation School 26 3.2 Five Manx Folk Dances 29 3.3 Consolidating the Canon 34 Chapter 4: The Development 4.1 Douglas and Stowell 37 4.2 Seven Manx Folk Dances 41 4.3 The Manx Folk Dance Society 42 Chapter 5: The Final Figure 5.1 The Manx Revival of the 1970s 50 5.2 Manx Dance Today 56 5.3 Conclusions -

Manx Gaelic and Physics, a Personal Journey, by Brian Stowell

keynote address Editors’ note: This is the text of a keynote address delivered at the 2011 NAACLT conference held in Douglas on The Isle of Man. Manx Gaelic and physics, a personal journey Brian Stowell. Doolish, Mee Boaldyn 2011 At the age of sixteen at the beginning of 1953, I became very much aware of the Manx language, Manx Gaelic, and the desperate situation it was in then. I was born of Manx parents and brought up in Douglas in the Isle of Man, but, like most other Manx people then, I was only dimly aware that we had our own language. All that changed when, on New Year’s Day 1953, I picked up a Manx newspaper that was in the house and read an article about Douglas Fargher. He was expressing a passionate view that the Manx language had to be saved – he couldn’t understand how Manx people were so dismissive of their own language and ignorant about it. This article had a dra- matic effect on me – I can say it changed my life. I knew straight off somehow that I had to learn Manx. In 1953, I was a pupil at Douglas High School for Boys, with just over two years to go before I possibly left school and went to England to go to uni- versity. There was no university in the Isle of Man - there still isn’t, although things are progressing in that direction now. Amazingly, up until 1992, there 111 JCLL 2010/2011 Stowell was no formal, official teaching of Manx in schools in the Isle of Man. -

Report of the Select Committee on the Registration of Land (Petition for Redress)

PP 2016/0078 REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE REGISTRATION OF LAND (PETITION FOR REDRESS) 2015-16 REPORT OF THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE REGISTRATION OF LAND (PETITION FOR REDRESS) On Wednesday 21st October 2015 it was resolved – That a committee of three Members be appointed with powers to take written and oral evidence pursuant to sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, as amended, to consider and to report to Tynwald by June 2016 on the Petition for Redress of John Ffynlo Craine and Annie Andrée Jeannine Hommet presented at St John’s on 6th July 2015 in relation to the registration of property. The powers, privileges and immunities relating to the work of a committee of Tynwald are those conferred by sections 3 and 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1876, sections 1 to 4 of the Privileges of Tynwald (Publications) Act 1973 and sections 2 to 4 of the Tynwald Proceedings Act 1984. Committee Membership Mr M R Coleman MLC (Chair) Mr G G Boot MHK (Glenfaba) Mr A L Cannan MHK (Michael) Copies of this Report may be obtained from the Tynwald Library, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IM1 3PW (Tel 01624 685520, Fax 01624 685522) or may be consulted at www.tynwald.org.im All correspondence with regard to this Report should be addressed to the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas IM1 3PW. Table of Contents I. THE COMMITTEE AND THE INVESTIGATION ................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND: THE REGISTRATION OF LAND IN THE ISLE OF MAN ................. 2 III. THE PETITION AND THE PETITIONERS’ PROPOSALS FOR REFORM .................. -

Culture Which Is As Evident Today As It Was 1,000’S of Years Ago

C U LT U R E The Isle of Man has a unique and varied culture which is as evident today as it was 1,000’s of years ago. Uncover the amazing history and heritage of the Island by following the ‘Story of Mann’ trail, whilst taking in some of the Island’s unique arts, folklore and cuisine along the way. THE STORY OF MANN Manx National Heritage reveals 10,000 years of Isle of Man history through the award-winning Story of Mann - a themed trail of presentations and attractions which takes you all over the Island. Start off by visiting the award-winning Manx Museum in Douglas for an overview and introduction to the trail before choosing your preferred destinations. Attractions on the trail include: Castle Rushen, Castletown. One of Europe’s best-preserved medieval castles, dating from the 12th Century. Detailed displays authentically recreate castle life as it was for the Kings and Lords of Mann. Cregneash Folk Village, near Port St Mary. Life as it was for 19th century crofters is authentically reproduced in this living museum of thatched whitewashed cottages and working farm. Great Laxey Wheel and Mines Trail, Laxey. The ‘Lady Isabella’ water wheel is the largest water wheel still operating in the world today. Built in 1854 to pump water from the mines, it is an important part of the Island’s once-thriving mining heritage. The old mines railway has now been restored. House of Mannanan, Peel. An interactive, state of the art heritage centre showing how the early Manx Celts and Viking settlers shaped the Island’s history. -

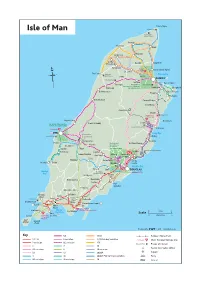

Isle of Man Bus Map.Ai

Point of Ayre Isle of Man Lighthouse Point of Ayre Visitor Centre Smeale The Lhen Bride Andreas Jurby East Jurby Regaby Dog Mills Threshold Sandygate Grove Grand Island Hotel St. Judes Museum The Cronk Ballaugh Ramsey Bay Old Church Garey Sulby RAMSEY Wildlife Park Lezayre Port e Vullen Curraghs For details of Albert Tower bus services in Ramsey, Ballaugh see separate map Lewaigue Maughold Bishopscourt Dreemskerry Hibernia Ballajora Kirk Michael Corony Bridge Glen Mona SNAEFELL Dhoon Laxey Wheel Dhoon Glen & Mines Trail Knocksharry Ballaragh Laxey For details of bus services Cronk-y-Voddy in Peel, see separate map Laxey Woollen Mills Old Laxey Peel Castle PEEL Laxey Bay Tynwald Mills Corrins Folly Tynwald Hill Ballabeg Ballacraine Baldrine Patrick For details of Halfway House Greeba bus services St. John’s in Douglas, Gordon Hope see separate map Groudle Glen and Railway Glenmaye Crosby Onchan Lower Foxdale Strang Governors Glen Vine Bridge Eairy Foxdale Union Mills Derby Niarbyl Dalby Braddan Castle NSC Douglas Bay Braaid Cooil DOUGLAS Niarbyl Rest Home Bay for Old Horses St. Mark’s Quines Hill Ballamodha Newtown Santon Port Soderick Orrisdale Silverdale Glen Bradda Ballabeg West Colby Level Cross Milners Tower Four Ballasalla Bradda Head Ways Ronaldsway Airport Port Erin Shore Hotel Castle Rushen Cregneash Bay ny The Old Grammar School Carrickey Castletown 03miles Port Scale Sound Cregneash St. Mary 05kilometres Village Folk Museum Calf Spanish of Man Head Produced by 1.9.10 www.fwt.co.uk Key 5/6 17/18 Railway / Horse Tram 1,11,12 6 variation 17/18 Sunday variation Peel Castle Manx National Heritage Site 2 variation 6C variation 17B Tynwald Mills Places of interest 3 7 19 Tourist Information Office 3A variation 8 19 variation X3 13 20/20A Airport 4 16 20/20A Point of Ayre variation Ferry 4A variation 16 variation 29 Seacat. -

Celtic Canons Craft and Craftsmen İn

Cinzia Yates British Forum for Ethnomusicology Conference 2008 Celtic Canons: Craft and craftsmen in Manx traditional music This paper will explore the relevance of craft as a canon forming force in the traditional music of the Isle of Man. In particular, it will invoke William Weber’s conception of canon in the western art tradition (2001), a conception that places craft as one of the central elements in canon formation and that relates craft to the craftsmanship of highly accomplished but usually professional composers. However, in Manx traditional music ‐ where authorship is usually unknown ‐ it would appear that Weber’s connection of craft to composer is not directly applicable. However, this paper will explore diachronically the relationship between craft and craftsmanship in the collection rather than in the composition of a relevant canon. In this respect, it will document the principal collectors and it will discuss the main arrangers of Manx traditional music. It will also look at the final stage of canon formation by focusing upon the folk revival where craftsmen were involved in the re‐ dissemination of earlier collected work. Further, the paper will consider the significance of craft and craftsmen for the modern Manx canon, paying especial attention to the role of connoisseurs in this matter. In sum, the paper will, once again, place craft at the centre of canon formation. In contrast to Weber, however, it will highlight the perception of craft and evaluate its meaning for a canonizing body. Canon Any discussion of canon is wrought with difficulties as a single definition of canon has not yet been agreed upon. -

Fíanaigecht in Manx Tradition FÍANAIGECHT in MANX TRADITION 1

Fíanaigecht in Manx Tradition FÍANAIGECHT IN MANX TRADITION 1 GEORGE BRODERICK University of Mannheim Introduction: The Finn Cycle In order to set the Manx examples of Fíanaigecht in context I cite here Bernhard Maier's short sketch of the Finn Cycle as it appears in Maier (1998: 118). Finn Cycle or Ossianic Cycle. The prose naratives and ballads centred upon the legendary hero Finn mac Cumaill and his retinue, the Fianna. They are set in the time of the king Cormac mac Airt at the beginning of the 3rdC AD. The heroes, apart from Finn, the leader of the Fianna, are his son Oisín, his grandson Oscar, and the warriors Caílte mac Rónáin, Goll mac Morna and Lugaid Lága. Most of the stories concerning F[inn] are about hunting adventures, love-affairs [...] and military disputes [...]. The most substantial work of this kind, combin- ing various episodes within a narrative framework, is Acallam na Senórach . The ballads concerning F[inn] gained in popularity from the later Middle Ages onwards and were the most important source of James Mac- pherson's "Works of Ossian" (Maier 1998: 118). The individual texts of the poems and ballads concerned with the Finn Cycle seemingly date over a period from the learned scribal tradition of the eleventh 2 to the later popular oral tradition of the early seventeenth century. Sixty-nine poems from this corpus survive in a single manuscript dating from 1626-27 known as Duanaire Finn ('Finn's poem book') (cf. Mac Neill 1908, Murphy 1933, 1953, Carey 2003). According to Ruairí Ó hUiginn (2003: 79), Duanaire Finn forms part of a long manuscript that was compiled in Ostend in 1626-7. -

P R O C E E D I N G S

T Y N W A L D C O U R T O F F I C I A L R E P O R T R E C O R T Y S O I K O I L Q U A I Y L T I N V A A L P R O C E E D I N G S D A A L T Y N HANSARD Douglas, Tuesday, 17th September 2019 All published Official Reports can be found on the Tynwald website: www.tynwald.org.im/business/hansard Supplementary material provided subsequent to a sitting is also published to the website as a Hansard Appendix. Reports, maps and other documents referred to in the course of debates may be consulted on application to the Tynwald Library or the Clerk of Tynwald’s Office. Volume 136, No. 19 ISSN 1742-2256 Published by the Office of the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 3PW. © High Court of Tynwald, 2019 TYNWALD COURT, TUESDAY, 17th SEPTEMBER 2019 PAGE LEFT DELIBERATELY BLANK ________________________________________________________________________ 2092 T136 TYNWALD COURT, TUESDAY, 17th SEPTEMBER 2019 Business transacted Questions for Written Answer .......................................................................................... 2097 1. Zero Hours Contract Committee recommendations – CoMin approval; progress; laying update report ........................................................................................................... 2097 2. GDPR breaches – Complaints and appeals made and upheld ........................................ 2098 3. No-deal Brexit – Updating guide for residents before 31st October 2019 ..................... 2098 4. No-deal Brexit – Food supply contingency plans; publishing CoMin paper.................... 2098 5. Tax returns – Number submitted April, May and June 2018; details of refunds ............ 2099 6. Common Purse Agreement – Consideration of abrogation ........................................... -

Publicindex Latest-19221.Pdf

ALPHABETICAL INDEX OF CHARITIES Registered in the Isle of Man under the Charities Registration and Regulation Act 2019 No. Charity Objects Correspondence address Email address Website Date Registered To advance the protection of the environment by encouraging innovation as to methods of safe disposal of plastics and as to 29-31 Athol Street, Douglas, Isle 1269 A LIFE LESS PLASTIC reduction in their use; by raising public awareness of the [email protected] www.alifelessplastic.org 08 Jan 2019 of Man, IM1 1LB environmental impact of plastics; and by doing anything ancillary to or similar to the above. To raise money to provide financial assistance for parents/guardians resident on the Isle of Man whose finances determine they are unable to pay costs themselves. The financial assistance given will be to provide full/part payment towards travel and accommodation costs to and from UK hospitals, purchase of items to help with physical/mental wellbeing and care in the home, Belmont, Maine Road, Port Erin, 1114 A LITTLE PIECE OF HOPE headstones, plaques and funeral costs for children and gestational [email protected] 29 Oct 2012 Isle of Man, IM9 6LQ aged to 16 years. For young adults aged 16-21 years who are supported by their parents with no necessary health/life insurance in place, financial assistance will also be looked at under the same rules. To provide a free service to parents/guardians resident on the Isle of Man helping with funeral arrangements of deceased children To help physically or mentally handicapped children or young Department of Education, 560 A W CLAGUE DECD persons whose needs are made known to the Isle of Man Hamilton House, Peel Road, 1992 Department of Education Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 5EZ Particularly for the purpose of abandoned and orphaned children of Romania. -

3. Celtic Languages

Freie Universität Berlin Fachbereich Philosophie und Geisteswissenschaften Appropriating New Technology for Minority Language Revitalization: The Welsh Case DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Vorgestellt von Mourad Ben Slimane Appropriating New Technology for Minority Language Revitalization Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. Gerhard Leitner 2. Prof. Dr. Carol W. Pfaff Disputation: Berlin, den 27.06.2008 2 Appropriating New Technology for Minority Language Revitalization Acknowledgments This dissertation would not have been written without the continuous support as well as great help of my dear Professor Gerhard Leitner. His expertise, understanding, and patience added considerably to my research experience. I would like to express my deep gratitude for him because it was his persistence and direction that encouraged me to complete my Ph.D. My special thanks goes out to Professor Carol W. Pfaff for giving me the opportunity to do a seminar on endangered languages at the John F. Kennedy Institute, which has been very useful for my thesis and professional experience. Thanks to Professor Peter Kunsmann, PD Dr.Volker Gast, and Dr. Florian Haas for kindly accepting to serve on my defense committee. I would also like to thank the Freie University of Berlin for the financial support that it provided me with to finish my research. The Welsh Language Board has also been very supportive in offering me recent literature on the development of Information Technology during my visit to Wales. Thanks to Grahame Davies from BBC Wales who provided me with many insights at different points in time with regard to Welsh new media and related matters. -

A Comparative Reading of Manx Cultural Revivals Breesha Maddrell Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 2 Cultural Survival Article 4 5-8-2006 Of Demolition and Reconstruction: a Comparative Reading of Manx Cultural Revivals Breesha Maddrell Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Part of the Celtic Studies Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Folklore Commons, History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Linguistics Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Maddrell, Breesha (2006) "Of Demolition and Reconstruction: a Comparative Reading of Manx Cultural Revivals," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol2/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Of Demolition and Reconstruction: a Comparative Reading of Manx Cultural Revivals Breesha Maddrell, Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool Abstract This paper accesses Manx cultural survival by examining the work of one of the most controversial of Manx cultural figures, Mona Douglas, alongside one of the most well loved, T.E. Brown. It uses the literature in the Isle of Man over the period 1880-1980 as a means of identifying attitudes toward two successive waves of cultural survival and revival. Through a reading of Brown's Prologue to the first series of Fo'c's'le Yarns, 'Spes Altera', "another hope", 1896, and Douglas' 'The Tholtan' – which formed part of her last collection of poetry, Island Magic, published in 1956 – the differing nationalist and revivalist roles of the two authors are revealed. -

Lewin2020.Pdf (4.103Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Aspects of the historical phonology of Manx Christopher Lewin Tràchdas airson ceum Dotair Feallsanachd Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2019 ii Declaration Tha mi a’ dearbhadh gur mise a-mhàin ùghdar an tràchdais seo, agus nach deach an obair a tha na bhroinn fhoillseachadh roimhe no a chur a-steach airson ceum eile. I confirm that this thesis has been composed solely by myself, and that the work contained within it has neither previously been published nor submitted for another degree. Christopher Lewin iii iv Geàrr-chunntas ’S e a tha fa-near don tràchdas seo soilleireachadh a thoirt seachad air grunn chuspairean ann an cinneachadh eachdraidheil fòn-eòlas Gàidhlig Mhanainn nach robhas a’ tuigsinn gu math roimhe seo.