Shouldered Hawk and Aplomado Falcon from Quaternary Asphalt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ECOLOGICAL REQUIREMENTS of the NEW ZEALAND FALCON (Falco Novaeseelandiae) in PLANTATION FORESTRY

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. THE ECOLOGICAL REQUIREMENTS OF THE NEW ZEALAND FALCON (Falco novaeseelandiae) IN PLANTATION FORESTRY A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Richard Seaton 2007 Adult female New Zealand falcon. D. Stewart 2003. “The hawks, eagles and falcons have been an inspiration to people of all races and creeds since the dawn of civilisation. We cannot afford to lose any species of the birds of prey without an effort commensurate with the inspiration of courage, integrity and nobility that they have given humanity…If we fail on this point, we fail in the basic philosophy of feeling a part of our universe and all that goes with it.” Morley Nelson, 2002. iii iv ABSTRACT Commercial pine plantations made up of exotic tree species are increasingly recognised as habitats that can contribute significantly to the conservation of indigenous biodiversity in New Zealand. Encouraging this biodiversity by employing sympathetic forestry management techniques not only offers benefits for indigenous flora and fauna but can also be economically advantageous for the forestry industry. The New Zealand falcon (Falco novaeseelandiae) or Karearea, is a threatened species, endemic to the islands of New Zealand, that has recently been discovered breeding in pine plantations. This research determines the ecological requirements of New Zealand falcons in this habitat, enabling recommendations for sympathetic forestry management to be made. -

Survival, Movements and Habitat Use of Aplomado Falcons Released in Southern Texas

THE JOURNAL OF RAPTOR RESEARCH A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE RAPTOR RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 30 DECEMBEg 1996 NO. 4 j. RaptorRes. 30(4):175-182 ¸ 1996 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. SURVIVAL, MOVEMENTS AND HABITAT USE OF APLOMADO FALCONS RELEASED IN SOUTHERN TEXAS CHRISTOPHERJ. PEREZ 1 New MexicoCooperative Fish and WildlifeResearch Unit, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. PHILLIPJ. ZWANK U.S. NationalBiological Service, New MexicoCooperative Fish and WildlifeResearch Unit, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. DAVID W. SMITH Departmentof ExperimentalStatistics, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. A•sTv,ACT.--Aplomado falcons (Falcofemoralis)formerly bred in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. Nest- ing in the U.S. waslast documentedin 1952. In 1986, aplomadofalcons were listed as endangeredand efforts to reestablishthem in their former range were begun by releasingcaptive-reared individuals in southern Texas. From 1993-94, 38 hatch-yearfalcons were released on Laguna AtascosaNational Wild- life Refuge.Two to 3 wk after release,28 falconswere recapturedfor attachmentof tail-mountedradio- transmitters.We report on survival,movements, and habitat use of these birds. In 1993 and 1994, four and five mortalities occurred within 2 and 4 wk of release, respectively.From 2-6 mo post-release,11 male and three female radio-taggedaplomado falcons used a home range of about 739 km• (range = 36-281 km2). Most movementsdid not extend beyond10 km from the refuge boundary,but a moni- tored male dispersed136 km north when 70 d old. Averagelinear distanceof daily movementswas 34 _+5 (SD) km. After falconshad been released75 d, they consistentlyused specific areas to forageand roost. -

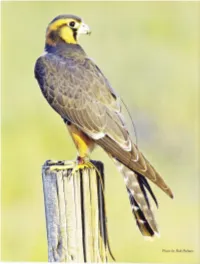

Hunting with the Aplomado Falcon in the U.S

!\ \ Pltrtto bt, Rob Palmer nalDd qoa q opqd flN ouolFurrrueg 'O'IA[ ururtul senruf 's'n, oql u gWoppurold wffipn Ig 'S'n aql ut uoJIeJ opeuoldy aqt qll^{ Surlung 32 Hunting with the Aplomado falcon in the U.S prey such as bobrvhites. Aplomado Falcons are social to the extent that mated pairs hunt together and catr be found together throughout the year and they hunt cooperativeli' r,vhen chasing avian prey. Siblings remain together for some time after becoming independent and hunt together. In Hector's study, birds account for an estirnated 97% of the prey biomass. Most birds are sized witl-r the smallest .J dove to robin being a hummingbird. The most ,-.€' commonly taken birds rvere lvhitc- '* winged doves, great tailed grackles. *.. * groove billed anis and yellorv billed cuckoos. Y had heard and read about I aolomado falcons bul ner er' I to have the op- portunity"lp".,"d to fly one. When I sarl that.|im Nelson, a falconer in Ken- newick, Washington, was breeding them, I thought long and hard about obtaining one. I currentl)' fly a f'emale peregrinc on ducks, pheasants and prairie chickens in Nebraska and I recentll' lost mv I'emale barbary'x merlin to a mptor. I love the stoop but I realll,missed thc pursuit flights at snrall avian quarry/. The advantage o1'{l,ving a "; pursuit falcon is that slips :rt small at,iau quar r)1 are plentifirl through- : r :E:= out the year and it is fiil-r to rvatch. I -.:13'.:::# knerv that purchasine an aplomado rvas going to be expensivc and thel' ilttthor ancl Sgt. -

Seasonal Diet of the Aplomado Falcon &Lpar;<I>Falco Femoralis</I>&Rpar

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS j RaptorRes. 39(1):55-60 ¸ 2005 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. SEASONALDIET OF THE APLOMADOFALCON (FALCOFEMORALIS) IN AN AGRtCULTURALARE• OF ARAUCAN•, SOUTHERN CHILE POCARDOA. FIGUEROAROJAS 1 AND EMA SOR•YACOMES STAPPUNG Estudiospara la Conservaci6ny Manejo de la Vida SilvestreConsultores, Blanco Encalada 350, Chilltin, Chile KEYWORDS: AplomadoFalcon; Falco femoralis; diet;agri- cania region, southern Chile. The landscape is com- cultural areas;,Chile. prised mainly of wheat and oat crops,scattered pasture and sedge-rush(Carex-Juncus spp.) marshes,small plan- The Aplomado Falcon (Falcofemoralis) is distributed tations of nonnativePinus spp. and Eucalyptusspp., and from southwesternUnited Statesto Tierra del Fuego Isla remnants of the native southern beech (Nothofagusspp.) forest. The climate is moist-temperatewith a Mediterra- Grande in southern Argentina and Chile. Aplomados in- nean influence (di Castriand Hajek 1976). Mean annual habit open areas such as savannas,desert grasslands,An- rainfall and temperatureare 1400 mm and 12øC,respec- dean and Patagonian steppes,and tree-lined pastures, tively. from coastalplains up to 4000 m in the Andes (Brown From August (austral winter) to December (austral and Areadon 1968, de la Pefia and Rumboll 1998). In spring-summer) 1997, we collected 65 pellets under the United States,the Aplomado Falcon is listed as en- trees and fence postsused as pluck sitesby at least one dangered (Shull 1986) due to the historical modification pair of AplomadoFalcons. We collected40 pelletsduring of its habitats and cumulative effects of DDT (Kiff et al. winter and 25 during spring-summer.A few prey remains 1980, Hector 1987). In contrast,the Chilean population were also collected beneath pluck sites during the may be increasing.Forest conversion to agricultural lands spring-summer period. -

Aplomado Falcon Abundance and Distribution in the Northern Chihuahuan Desert of Mexico

THE JOURNAL OF RAPTOR RESEARCH A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE RAPTOR RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 38 JUNF,2004 NO. 2 j Raptorlies. 38(2):107-117 ¸ 2004 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. APLOMADO FALCON ABUNDANCE AND DISTRIBUTION IN THE NORTHERN CHIHUAHUAN DESERT OF MEXICO KENDAL E. YOUNG 1 AND BRUCE C. THOMPSON 2 NewMexico Cooperative Fish and WildliJbResearch Unit and Fisheryand Wildli? SciencesDepartment, Box 30003, MSC 4901, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. ALBERTO LAF(SN TERRAZAS Facultad de Zootecnia, UniversidadAut6noma de Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico ANGEL B. MONTOYA ThePeregrine Fund, Boise,11) 83709 U.S.A. RAUL VALDEZ Fisheryand WildliJkSdences Department, Box 30003, MSC 4901, NewMexico State University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. AnSTRACT.--Thenorthern Aplomado Falcon (Falcofemoralis septentrionalis) historically occupied coastal prairies, savannas,and desert grasslandsfrom southern Mexico north to southern and southwestern Texas,southern New Mexico, and southeasternArizona. Current residentAplomado Falconpopulations are primarily in Mexico, with isolatedpopulations in southernTexas and from northern Chihuahuato southern New Mexico. We conductedsurveys in semidesertgrasslands/savannas and associatedhabitats in northern Chihuahua to locate Aplomado Falconsand to better delineate their distribution and abundancein the northern Chihuahuan Desert during 1998-99. Data were collectedby surveyinglarge tracts,transects in nonrandomlyselected grasslands, and from a falcon monitoring study.Based on all surveyeffort, the minimum knownpopulation of adult Aplomado Falconsin the studyarea in northern Chihuahua was79 individuals.Aplomado Falconswere primarily associatedwith grasslandcommunities. Most falcon nests (88%) were found in grasslandcommunities with soaptreeyucca (Yuccaelata) or Torrey yucca (Y. torreyi).Aplomado Falconswere found fairly clusteredin the north-centralto north- eastern part of the study area. -

Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 Migratory Bird Program Table of Contents

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 Migratory Bird Program Table Of Contents Executive Summary 4 Acknowledgments 5 Introduction 6 Methods 7 Geographic Scope 7 Birds Considered 7 Assessing Conservation Status 7 Identifying Birds of Conservation Concern 10 Results and Discussion 11 Literature Cited 13 Figures 15 Figure 1. Map of terrestrial Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs) Marine Bird Conservation Regions (MBCRs) of North America (Bird Studies Canada and NABCI 2014). See Table 2 for BCR and MBCR names. 15 Tables 16 Table 1. Island states, commonwealths, territories and other affiliations of the United States (USA), including the USA territorial sea, contiguous zone and exclusive economic zone considered in the development of the Birds of Conservation Concern 2021. 16 Table 2. Terrestrial Bird Conservation Regions (BCR) and Marine Bird Conservation Regions (MBCR) either wholly or partially within the jurisdiction of the Continental USA, including Alaska, used in the Birds of Conservation Concern 2021. 17 Table 3. Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 in the Continental USA (CON), continental Bird Conservation Regions (BCR), Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands (PRVI), and Hawaii and Pacific Islands (HAPI). Refer to Appendix 1 for scientific names of species, subspecies and populations Breeding (X) and nonbreeding (nb) status are indicated for each geography. Parenthesized names indicate conservation concern only exists for a specific subspecies or population. 18 Table 4. Numbers of taxa of Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 represented on the Continental USA (CON), continental Bird Conservation Region (BCR), Puerto Rico and VirginIslands (PRVI), Hawaii and Pacific Islands (HAPI) lists by general taxonomic groups. Also presented are the unique taxa represented on all lists. -

CHAMBERS, S. 2009. Birds of New Zealand - Locality Guide

CHAMBERS, S. 2009. Birds of New Zealand - Locality Guide. 3rd edn. Arun Books, Orewa, New Zealand. New Zealand falcon: pp 121-123. NEW ZEALAND FALCON. Family Falconidae Species Falco novaeseelandiae Common names New Zealand Falcon, Bush Falcon, Sparrowhawk Status Endemic Size 430 mm (cf sparrow 145 mm, Harrier 550mm) Habitat The Bush Falcon and Southern Falcon are confined to forested areas while the Eastern Falcon is widely spread over pastureland and rough and open high country. In recent years there has been some artificial breeding of falcons in the Nelson area as a means to reducing pest birds in vineyards. New Zealand range In the North Island widespread south of a line from Kawhia Harbour to the central Bay of Plenty. In the South Island it is widespread throughout but nowhere common. Also on Stewart Island and Auckland Island. Discussion The Bush Falcon is an endemic species which is not grouped with any of the five species of Australian falcons. Instead it is grouped with three species known from the southern American states of Texas and New Mexico and from Central America and northern South America (Cade T J 1982). These species are the Orange-breasted Falcon (F. deiroleucus), the Bat Falcon (F. rufigularis) and the Aplomado Falcon (F. femoralis). Its relationship with these Birds Locality - PDFs.indd 213 10/15/2011 8:13:44 PM three species is to do with similarities of bill shape, tail colouring, sunbathing habits, the excretory habits of nestlings and with their carnivorous eating habits and hunting techniques. The ancestor of the New Zealand Falcon is considered to have been an early arrival to New Zealand, it adapting to the New Zealand environment and even progressing towards tameness as did other endemic and ancient species. -

Learn About Texas Birds Activity Book

Learn about . A Learning and Activity Book Color your own guide to the birds that wing their way across the plains, hills, forests, deserts and mountains of Texas. Text Mark W. Lockwood Conservation Biologist, Natural Resource Program Editorial Direction Georg Zappler Art Director Elena T. Ivy Educational Consultants Juliann Pool Beverly Morrell © 1997 Texas Parks and Wildlife 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 PWD BK P4000-038 10/97 All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems – without written permission of the publisher. Another "Learn about Texas" publication from TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE PRESS ISBN- 1-885696-17-5 Key to the Cover 4 8 1 2 5 9 3 6 7 14 16 10 13 20 19 15 11 12 17 18 19 21 24 23 20 22 26 28 31 25 29 27 30 ©TPWPress 1997 1 Great Kiskadee 16 Blue Jay 2 Carolina Wren 17 Pyrrhuloxia 3 Carolina Chickadee 18 Pyrrhuloxia 4 Altamira Oriole 19 Northern Cardinal 5 Black-capped Vireo 20 Ovenbird 6 Black-capped Vireo 21 Brown Thrasher 7Tufted Titmouse 22 Belted Kingfisher 8 Painted Bunting 23 Belted Kingfisher 9 Indigo Bunting 24 Scissor-tailed Flycatcher 10 Green Jay 25 Wood Thrush 11 Green Kingfisher 26 Ruddy Turnstone 12 Green Kingfisher 27 Long-billed Thrasher 13 Vermillion Flycatcher 28 Killdeer 14 Vermillion Flycatcher 29 Olive Sparrow 15 Blue Jay 30 Olive Sparrow 31 Great Horned Owl =female =male Texas Birds More kinds of birds have been found in Texas than any other state in the United States: just over 600 species. -

Cooperative Hunting and Its Relationship to Foraging Success and Prey Size in an Avian Predator

Ethology 73, 247-257 (1986) © 1986 Paul Parey Scientific Publishers, Berlin and Hamburg ISSN 0179-1613 1 ,- Department of Biology, University of California, Los Angeles Cooperative Hunting and its Relationship to Foraging Success and Prey Size in an Avian Predator DEAN p. HECTOR With 2 figures Received: December 31, 1985 Accepted: Apri/16, 1986 Abstract Aplomado falcons (Falco femora/is) often hunt in pairs when chasing birds; 29 % of 349 hunts observed in eastern Mexico involved mated pairs of falcons simultaneously chasing the same prey animal; and 66 % of 100 hunts of birds were tandem pursuits. Although true cooperative hunting is uncommon in birds of prey, hunts by pairs of Aplomado falcons consistently showed signs of cooperative behavior such as use of a simple coordinative signal, and some division of labor between participating individuals. Pairs were more than twice as successful as solo falcons hunting birds (44 % vs. 19 % ), however, there was no evidence that cooperative hunting increased the range of feasible prey sizes. The frequent use of cooperative foraging in this and similar species may relate to necessities of efficient nest defense, and food and nest procurement in savannas inhabited by a diversity of nest site predators. J Introduction Despite their reputation as solitary hunters, birds of prey often engage in various types of social foraging behavior. Most commonly, individuals hunt in flocks with little or no coordination among members. This occurs in the western red-legged falcon (Falco vespertinus; CRAMP & SIMMONS 1980), Swainson's hawk (Buteo swainsoni; BENT 1937), snail kite (Rhostramus sociabilis; BROWN & AMA DON 1968), and tawny eagle (Aquila rapax; CRAMP & SIMMONS 1980), species which feed on invertebrates and small terrestrial vertebrates. -

Corales Stappung, ES. "Comparación De La Dieta Estival Del Halco

Comparación de la dieta estival del halconcito colorado (Falco sparverius ) y el halcón plomizo (Falco femoralis) en un área agrícola de la araucaría, Sur de Chile Figueroa Rojas, R. A.; Corales Stappung, E. S. 2004 Cita: Figueroa Rojas, R. A.; Corales Stappung, E. S. (2004) Comparación de la dieta estival del halconcito colorado (Falco sparverius ) y el halcón plomizo (Falco femoralis) en un área agrícola de la araucaría, Sur de Chile. Hornero 019 (02) : 053-060 www.digital.bl.fcen.uba.ar Puesto en linea por la Biblioteca Digital de la Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales Universidad de Buenos Aires 2004Hornero 19(2):53–60, 2004DIET OF THE AMERICAN KESTREL AND APLOMADO FALCON 53 SUMMER DIET COMPARISON BETWEEN THE AMERICAN KESTREL (FALCO SPARVERIUS) AND APLOMADO FALCON (FALCO FEMORALIS) IN AN AGRICULTURAL AREA OF ARAUCANÍA, SOUTHERN CHILE RICARDO A. FIGUEROA ROJAS 1,2 AND E. SORAYA CORALES STAPPUNG 1 1 Estudios para la Conservación y Manejo de la Vida Silvestre Consultores. Blanco Encalada 350, Chillán, Chile. 2 [email protected] ABSTRACT.— The diet of the American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) and Aplomado Falcon (Falco femoralis) was quantified by analysis of their pellets during the summer 1997-1998 in an agricul- tural area of Araucanía, southern Chile. By number, the most important prey of the American Kestrel were insects (61% of all individual prey) followed by birds (23%), rodents (13.7%) and reptiles (2.6%). Avian prey accounted for the highest biomass contribution (79.6%), followed by rodents (18%). Biomass contribution of insects and reptiles was negligible. Birds were the staple prey of the Aplomado Falcon both by number (89%) and biomass (99%). -

Species Risk Assessment

Ecological Sustainability Analysis of the Kaibab National Forest: Species Diversity Report Ver. 1.2 Prepared by: Mikele Painter and Valerie Stein Foster Kaibab National Forest For: Kaibab National Forest Plan Revision Analysis 22 December 2008 SpeciesDiversity-Report-ver-1.2.doc 22 December 2008 Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................................. i Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 PART I: Species Diversity.............................................................................................................. 1 Species List ................................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria .................................................................................................................................... 2 Assessment Sources................................................................................................................ 3 Screening Results.................................................................................................................... 4 Habitat Associations and Initial Species Groups........................................................................ 8 Species associated with ecosystem diversity characteristics of terrestrial vegetation or aquatic systems ...................................................................................................................... -

6666 Federal Register / Vol. 51, No. 37 / Tuesday, February 25, 1986 / Rujes and Regulations

6666 Federal Register / Vol. 51, No. 37 / Tuesday, February 25, 1986 / RuJes and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INiERlOR kestrels (FaIco sparverius) and implicate habitat degradation due to peregrine falcon! (Fake peregrinus). brush encroachment as the main factor Fish and Wildllfe Service , The northern aplomado falcon does not responsible for the disappearance of the seem to be migratory, since most subspecies from the United States. 50 CFR Part 17 collected adults were taken in winter Secondarily, overcollecting of the Endangered and Threatened Wildlife months in the United States (Hector falcons and their eggs may have and Plants; Determination of the 1981). Hector (1960,1981,1982,1983) temporarily reduced their numbers in Nodhem Aplomado Falcon lo Be an summarized the literature dealing with some parts of the United States. Endangered Species the northern aplomado falcon and However, collecting pressure, by itself, reported on the historic and recent could not account for the continued AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, distributions of the species, and on its absence of the aplomado falcon north of Interior. habitat, diet, and behavior. Kiff et al, Mexico. Currently, the most serious ACTION: Final rule. (1978) documented eggshell thinning and threat to this falcon is the continued uee pesticide contamination in the of DDT and other persistent pesticides SUMMARY: The Service determines the subspecies. within the ranges of the falcon and some northern aplomado falcon, Fake Egg laying has been recorded betwien of its prey species. femoralis septentrionuh, to be an the months of January and September FaIco femomiis septentrionalis ws endangered species under provisions of eggs are usually laid in April or May, first considered by the Service in 1973 as the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as Aplomado falcons feed on birds, insects, a possible candidate for endangered amended.