An Observation of a Pair of Aplomado Falcons Falco Femoralis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ECOLOGICAL REQUIREMENTS of the NEW ZEALAND FALCON (Falco Novaeseelandiae) in PLANTATION FORESTRY

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. THE ECOLOGICAL REQUIREMENTS OF THE NEW ZEALAND FALCON (Falco novaeseelandiae) IN PLANTATION FORESTRY A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Richard Seaton 2007 Adult female New Zealand falcon. D. Stewart 2003. “The hawks, eagles and falcons have been an inspiration to people of all races and creeds since the dawn of civilisation. We cannot afford to lose any species of the birds of prey without an effort commensurate with the inspiration of courage, integrity and nobility that they have given humanity…If we fail on this point, we fail in the basic philosophy of feeling a part of our universe and all that goes with it.” Morley Nelson, 2002. iii iv ABSTRACT Commercial pine plantations made up of exotic tree species are increasingly recognised as habitats that can contribute significantly to the conservation of indigenous biodiversity in New Zealand. Encouraging this biodiversity by employing sympathetic forestry management techniques not only offers benefits for indigenous flora and fauna but can also be economically advantageous for the forestry industry. The New Zealand falcon (Falco novaeseelandiae) or Karearea, is a threatened species, endemic to the islands of New Zealand, that has recently been discovered breeding in pine plantations. This research determines the ecological requirements of New Zealand falcons in this habitat, enabling recommendations for sympathetic forestry management to be made. -

Life History Account for Peregrine Falcon

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group PEREGRINE FALCON Falco peregrinus Family: FALCONIDAE Order: FALCONIFORMES Class: AVES B129 Written by: C. Polite, J. Pratt Reviewed by: L. Kiff Edited by: L. Kiff DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY Very uncommon breeding resident, and uncommon as a migrant. Active nesting sites are known along the coast north of Santa Barbara, in the Sierra Nevada, and in other mountains of northern California. In winter, found inland throughout the Central Valley, and occasionally on the Channel Islands. Migrants occur along the coast, and in the western Sierra Nevada in spring and fall. Breeds mostly in woodland, forest, and coastal habitats. Riparian areas and coastal and inland wetlands are important habitats yearlong, especially in nonbreeding seasons. Population has declined drastically in recent years (Thelander 1975,1976); 39 breeding pairs were known in California in 1981 (Monk 1981). Decline associated mostly with DDE contamination. Coastal population apparently reproducing poorly, perhaps because of heavier DDE load received from migrant prey. The State has established 2 ecological reserves to protect nesting sites. A captive rearing program has been established to augment the wild population, and numbers are increasing (Monk 1981). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: Swoops from flight onto flying prey, chases in flight, rarely hunts from a perch. Takes a variety of birds up to ducks in size; occasionally takes mammals, insects, and fish. In Utah, Porter and White (1973) reported that 19 nests averaged 5.3 km (3.3 mi) from the nearest foraging marsh, and 12.2 km (7.6 mi) from the nearest marsh over 130 ha (320 ac) in area. -

Shouldered Hawk and Aplomado Falcon from Quaternary Asphalt

MARCH 2003 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 71 J. RaptorRes. 37(1):71-75 ¸ 2003 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. RED-SHOULDEREDHAWK AND APLOMADO FALCON FROM QUATERNARY ASPHALT DEPOSITS IN CUBA WILLIAM SU•REZ MuseoNacional de Historia Natural, Obispo61, Plaza deArmas; La Habana CP 10100 Cuba STORRS L. OLSON • NationalMuseum of Natural History,Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 U.S.A. KEYWORDS: AplomadoFalcon; Falco femoralis;Red-shoul- MATERIAL EXAMINED deredHawk; Buteo lineatus;Antilles; Cuba; extinctions; Jbssil Fossils are from the collections of the Museo Nacional birds;Quaternary; West Indies. de Historia Natural, La Habana, Cuba (MNHNCu). Mod- ern comparativeskeletons included specimensof all of The fossil avifauna of Cuba is remarkable for its diver- the speciesof Buteoand Falcoin the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, sity of raptors,some of very large size, both diurnal and DC (USNM). The following specimenswere used tbr the nocturnal (Arredondo 1976, 1984, Su'•rez and Arredon- tables of measurements: Buteo lineatus 16633-16634, do 1997). This diversitycontinues to increase(e.g., Su'•- 17952-17953, 18798, 18846, 18848, 18965, 19108, 19929, rez and Olson 2001a, b, 2003a) and many additionalspe- 290343, 291174-291175, 291197-291200, 291216, cies are known that await description. Not all of the 291860-291861, 291883, 291886, 296343, 321580, raptors that have disappearedfrom Cuba in the Quater- 343441, 499423, 499626, 499646, 500999-501000, nary are extinct species,however. We report here the first 610743-610744, 614338; Falcofemoralis 30896, 291300, 319446, 622320-622321. recordsfor Cuba of two widespreadliving speciesthat are not known in the Antilles today. Family Accipitridae Thesefossils were obtainedduring recentpaleontolog- Genus ButeoLacepede ical exploration of an asphalt deposit, Las Breasde San Red-shouldered Hawk Buteolineatus (Gmelin) Felipe, which is so far the only "tar pit" site known in (Fig. -

Falco Peregrinus Tunstall Peregrineperegrine Falcon,Falcon Page 1

Falco peregrinus Tunstall peregrineperegrine falcon,falcon Page 1 State Distribution Best Survey Period Copyright: Rick Baetsen Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Status: State Endangered Dakota, Florida, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, and Nevada. In Mexico, Global and state rank: G4/S1 peregrine falcon is present on the Baja Peninsula, islands of the Gulf of California, and northwestern Family: Falconidae – Falcons states of the mainland. Breeding also confirmed for eastern Cuba and the Dominican Republic (White et al. Total range: While having one of the most extensive 2002). global distributions, peregrine falcons were never abundant anywhere, due to its specific habitat State distribution: Barrows (1912) noted that the requirements and position in the food web as a top peregrine falcon was “nowhere common” and Wood predator (Hess 1991). The species was formerly (1951) called the species a rare local summer resident extirpated throughout much of its original range due to in northern counties along the Great Lakes. Isaacs exposure to organic chemicals such as DDT, and (1976) described ten historical nesting sites in Michigan: reoccupancy and restoration is still incomplete (White et Goose Lake escarpments, Huron Islands, Huron al. 2002). Three subspecies occur in North America, Mountains, and Lake Michigamme in Marquette with F. p. anatum being the subspecies that breeds in County; Grand Island and Pictured Rocks in Alger Michigan. Payne (1983) noted that F. p. tundrius is an County; Garden Peninsula of Delta County; Isle Royale occasional transient in the State. See White et al. in Keweenaw County; Mackinac Island in Mackinac (2002) and citations therein for a detailed description of County; and South Fox Island in Leelanau County. -

Syringeal Morphology and the Phylogeny of the Falconidae’

The Condor 96:127-140 Q The Cooper Ornithological Society 1994 SYRINGEAL MORPHOLOGY AND THE PHYLOGENY OF THE FALCONIDAE’ CAROLES.GRIFFITHS Departmentof Ornithology,American Museum of NaturalHistory and Departmentef Biology, City Collegeof City Universityof New York, Central Park West at 79th St., New York, NY 10024 Abstract. Variation in syringealmorphology was studied to resolve the relationshipsof representativesof all of the recognized genera of falcons, falconets, pygmy falcons, and caracarasin the family Falconidae. The phylogenyderived from thesedata establishesthree major cladeswithin the family: (1) the Polyborinae, containingDaptrius, Polyborus, Milvago and Phalcoboenus,the four genera of caracaras;(2) the Falconinae, consistingof the genus Falco, Polihierax (pygmy falcons),Spiziapteryx and Microhierax (falconets)and Herpetothe- res (Laughing Falcon); and (3) the genus Micrastur(forest falcons) comprising the third, basal clade. Two genera, Daptriusand Polihierax,are found to be polyphyletic. The phy- logeny inferred from these syringealdata do not support the current division of the family into two subfamilies. Key words: Falconidae;phylogeny; systematics; syrinx; falcons; caracaras. INTRODUCTION 1. The Polyborinae. This includes seven gen- Phylogenetic relationships form the basis for re- era: Daptrius, Milvago, Polyborus and Phalco- searchin comparative and evolutionary biology boenus(the caracaras),Micrastur (forest falcons), (Page1 and Harvey 1988, Gittleman and Luh Herpetotheres(Laughing Falcon) and Spiziapter- 1992). Patterns drawn from cladogramsprovide yx (Spot-winged Falconet). the blueprints for understanding biodiversity, 2. The Falconinae. This includes three genera: biogeography,behavior, and parasite-hostcospe- Falco, Polihierax (pygmy falcons) and Micro- ciation (Vane-Wright et al. 199 1, Mayden 1988, hierax (falconets). Page 1988, Coddington 1988) and are one of the Inclusion of the caracarasin the Polyborinae key ingredients for planning conservation strat- is not questioned (Sharpe 1874, Swann 1922, egies(Erwin 199 1, May 1990). -

Peregrine Falcon Falco Peregrinus Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata the Peregrine Falcon Is Also Known As the Duck Class: Aves Hawk

peregrine falcon Falco peregrinus Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The peregrine falcon is also known as the duck Class: Aves hawk. It averages 15 to 20 inches in length (tail tip to Order: Falconiformes bill tip in preserved specimen). Like all falcons, it has pointed wings, a thin tail and a quick, flapping Family: Falconidae motion in flight. The peregrine’s dark “sideburns” ILLINOIS STATUS are distinctive. The adult has a blue-gray back, while the chest and belly are white to orange with darker common, native spots and bars. The immature falcon has the same head and facial patterns as the adult but is brown on the upper side. The lower side of the immature bird is cream-colored with brown streaks. BEHAVIORS The peregrine falcon is a migrant, winter resident and summer resident in Illinois. It was extirpated from the state, reintroduced and populations have recovered. The peregrine falcon lives in open areas, like prairies, along Lake Michigan and around other rivers and lakes, especially if large flocks of shorebirds and waterfowl are present. It has also been introduced to cities. Spring migrants begin arriving in March. These birds previously nested in adult Illinois on cliffs and in hollow trees but now may nest on ledges or roofs of tall buildings or bridge © Chris Young, Wildlife CPR structures in urban areas. Three or four, white eggs with dark markings are deposited by the female, and she incubates them for the entire 33- to 35-day, incubation period. Fall migrants begin arriving in Illinois in August. This bird winters as far south as the southern tip of South America. -

Survival, Movements and Habitat Use of Aplomado Falcons Released in Southern Texas

THE JOURNAL OF RAPTOR RESEARCH A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE RAPTOR RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 30 DECEMBEg 1996 NO. 4 j. RaptorRes. 30(4):175-182 ¸ 1996 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. SURVIVAL, MOVEMENTS AND HABITAT USE OF APLOMADO FALCONS RELEASED IN SOUTHERN TEXAS CHRISTOPHERJ. PEREZ 1 New MexicoCooperative Fish and WildlifeResearch Unit, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. PHILLIPJ. ZWANK U.S. NationalBiological Service, New MexicoCooperative Fish and WildlifeResearch Unit, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. DAVID W. SMITH Departmentof ExperimentalStatistics, New MexicoState University, Las Cruces,NM 88003 U.S.A. A•sTv,ACT.--Aplomado falcons (Falcofemoralis)formerly bred in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. Nest- ing in the U.S. waslast documentedin 1952. In 1986, aplomadofalcons were listed as endangeredand efforts to reestablishthem in their former range were begun by releasingcaptive-reared individuals in southern Texas. From 1993-94, 38 hatch-yearfalcons were released on Laguna AtascosaNational Wild- life Refuge.Two to 3 wk after release,28 falconswere recapturedfor attachmentof tail-mountedradio- transmitters.We report on survival,movements, and habitat use of these birds. In 1993 and 1994, four and five mortalities occurred within 2 and 4 wk of release, respectively.From 2-6 mo post-release,11 male and three female radio-taggedaplomado falcons used a home range of about 739 km• (range = 36-281 km2). Most movementsdid not extend beyond10 km from the refuge boundary,but a moni- tored male dispersed136 km north when 70 d old. Averagelinear distanceof daily movementswas 34 _+5 (SD) km. After falconshad been released75 d, they consistentlyused specific areas to forageand roost. -

Hunting with the Aplomado Falcon in the U.S

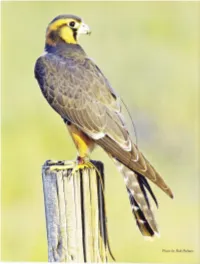

!\ \ Pltrtto bt, Rob Palmer nalDd qoa q opqd flN ouolFurrrueg 'O'IA[ ururtul senruf 's'n, oql u gWoppurold wffipn Ig 'S'n aql ut uoJIeJ opeuoldy aqt qll^{ Surlung 32 Hunting with the Aplomado falcon in the U.S prey such as bobrvhites. Aplomado Falcons are social to the extent that mated pairs hunt together and catr be found together throughout the year and they hunt cooperativeli' r,vhen chasing avian prey. Siblings remain together for some time after becoming independent and hunt together. In Hector's study, birds account for an estirnated 97% of the prey biomass. Most birds are sized witl-r the smallest .J dove to robin being a hummingbird. The most ,-.€' commonly taken birds rvere lvhitc- '* winged doves, great tailed grackles. *.. * groove billed anis and yellorv billed cuckoos. Y had heard and read about I aolomado falcons bul ner er' I to have the op- portunity"lp".,"d to fly one. When I sarl that.|im Nelson, a falconer in Ken- newick, Washington, was breeding them, I thought long and hard about obtaining one. I currentl)' fly a f'emale peregrinc on ducks, pheasants and prairie chickens in Nebraska and I recentll' lost mv I'emale barbary'x merlin to a mptor. I love the stoop but I realll,missed thc pursuit flights at snrall avian quarry/. The advantage o1'{l,ving a "; pursuit falcon is that slips :rt small at,iau quar r)1 are plentifirl through- : r :E:= out the year and it is fiil-r to rvatch. I -.:13'.:::# knerv that purchasine an aplomado rvas going to be expensivc and thel' ilttthor ancl Sgt. -

Falco Columbarius Linnaeus Merlin,Merlin Page 1

Falco columbarius Linnaeus Merlin,merlin Page 1 State Distribution Best Survey Period Photo by: Charles W. Cook Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Status: State threatened Schoolcraft) and two northern lower Peninsula counties (Alpena, Antrim). The highest density of nesting merlins Global and state ranks: G5/S1S2 occurs on Isle Royale. Pairs are also sighted annually in the Porcupine Mountains State Park, Ontonagon County, Family: Falconidae (falcons) and in the Huron Mountains, Marquette County. During migration, merlins can be spotted throughout the state. Total Range: Found throughout the northern hemi- sphere, Falco columbarius, in North America occurs in Recognition: The merlin is a medium-sized falcon, the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada south to the about the size of a blue jay, characterized by long, extreme northern portions of the United States, from the pointed wings and rapid wing-beats; a long, heavily Rockies to Maine (Johnsgard 1990). The paler subspe- barred tail; vertically streaked underparts; and faint cies, F. c. richardsoni, breeds in the prairie parklands of “sideburns.” In flight, merlins appear similar to Ameri- central Canada and the darker subspecies F. c. can kestrels (F. sparverius) but lack any brown tones suckleyi, breeds in the Pacific coastal regions. The above or extensive buffy to white underparts (Johnsgard more widespread F. c. columbarius, occupies the 1990). The dark tail with 2-5 highly contrasting remaining range. The merlin winters from the Gulf of narrow light bands helps distinguish the merlin from Mexico to northern South America. the larger peregrine falcon (F. peregrinus) (Sodhi et al. -

1/9/2015 1 G Phylum Chordata Characteristics – May Be With

1/9/2015 Vertebrate Evolution Z Phylum Chordata characteristics – may be with organism its entire life or only during a certain developmental stage 1. Dorsal, hollow nerve cord 2. Flexible supportive rod (notochord) running along dorsum just ventral to nerve cord 3. Pharyngeal slits or pouches 4. A tail at some point in development Z Phylum Chordata has 3 subphyla W Urochordata – tunicates Z Adults are sessile marine animals with gill slits Z Larvae are free-swimming and possess notochord and nerve cord in muscular tail Z Tail is reabsorbed when larvae transforms into an adult 1 1 1/9/2015 W Cephalochordata –lancelets Z Small marine animals that live in sand in shallow water Z Retains gill slits, notochord, and nerve cord thru life W Vertebrata – chordates with a “backbone” Z Persistent notochord, or vertebral column of bone or cartilage Z All possess a cranium Z All embryos pass thru a stage when pharyngeal pouches are present Lamprey ammocoete 2 2 1/9/2015 Jawless Fish Hagfish Lamprey Vertebrate Evolution 1. Tunicate larvae 2. Lancelet 3. Larval lamprey (ammocoete) and jawless fishes 4. Jaw development from anterior pharyngeal arches – capture and ingestion of more food sources 5. Paired fin evolution A. Eventually leads to tetrapod limbs B. Fin spine theory – spiny sharks (acanthodians) had up to 7 pairs of spines along trunk and these may have led to front and rear paired fins 3 3 1/9/2015 Z Emergence onto land W Extinct lobe-finned fishes called rhipidistians seem to be the most likely tetrapod ancestor Z Similar to modern lungfish -

Seasonal Diet of the Aplomado Falcon &Lpar;<I>Falco Femoralis</I>&Rpar

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS j RaptorRes. 39(1):55-60 ¸ 2005 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. SEASONALDIET OF THE APLOMADOFALCON (FALCOFEMORALIS) IN AN AGRtCULTURALARE• OF ARAUCAN•, SOUTHERN CHILE POCARDOA. FIGUEROAROJAS 1 AND EMA SOR•YACOMES STAPPUNG Estudiospara la Conservaci6ny Manejo de la Vida SilvestreConsultores, Blanco Encalada 350, Chilltin, Chile KEYWORDS: AplomadoFalcon; Falco femoralis; diet;agri- cania region, southern Chile. The landscape is com- cultural areas;,Chile. prised mainly of wheat and oat crops,scattered pasture and sedge-rush(Carex-Juncus spp.) marshes,small plan- The Aplomado Falcon (Falcofemoralis) is distributed tations of nonnativePinus spp. and Eucalyptusspp., and from southwesternUnited Statesto Tierra del Fuego Isla remnants of the native southern beech (Nothofagusspp.) forest. The climate is moist-temperatewith a Mediterra- Grande in southern Argentina and Chile. Aplomados in- nean influence (di Castriand Hajek 1976). Mean annual habit open areas such as savannas,desert grasslands,An- rainfall and temperatureare 1400 mm and 12øC,respec- dean and Patagonian steppes,and tree-lined pastures, tively. from coastalplains up to 4000 m in the Andes (Brown From August (austral winter) to December (austral and Areadon 1968, de la Pefia and Rumboll 1998). In spring-summer) 1997, we collected 65 pellets under the United States,the Aplomado Falcon is listed as en- trees and fence postsused as pluck sitesby at least one dangered (Shull 1986) due to the historical modification pair of AplomadoFalcons. We collected40 pelletsduring of its habitats and cumulative effects of DDT (Kiff et al. winter and 25 during spring-summer.A few prey remains 1980, Hector 1987). In contrast,the Chilean population were also collected beneath pluck sites during the may be increasing.Forest conversion to agricultural lands spring-summer period. -

Chronic Salpingitis in Collared Forest-Falcon (Micrastur Semitorquatus - Vieillot, 1817)

ISSN 2447-0716 Alm. Med. Vet. Zoo. 12 CHRONIC SALPINGITIS IN COLLARED FOREST-FALCON (MICRASTUR SEMITORQUATUS - VIEILLOT, 1817) SALPINGITE CRÔNICA EM GAVIÃO-RELÓGIO (MICRASTUR SEMITORQUATUS - VIEILLOT, 1817) Guilherme Augusto Marietto-Gonçalves* Ewerton Luiz de Lima†, Alexandre Alberto Tonin‡ RESUMO O presente artigo notifica a ocorrência de salpingite crônica em um exemplar de Micrastur semitorquatus cativo, com sete anos de idade, ocorrido no período de seis meses após a submissão de um procedimento emergencial de ovocentese. Devido a apresentação constante de apatia e dificuldade respiratória e de um aumento de volume abdominal a ave seria analisada para a realização de uma laparotomia exploratória. No início de um procedimento anestésico, durante a indução anestésica a ave veio a óbito e no exame necroscópico encontrou-se o oviduto com aumento de tamanho e com deformação anatômica e ao analisar órgão viu-se que estava repleto de conteúdo caseoso e com duas massas ovais de aspecto pútrido. O exame histopatológico revelou um quadro de metrite no terço proximal do oviduto. Apesar de não ter sido realizado uma avaliação microbiológico o quadro observado é compatível com salpingite por colibacilose ascendente. A realização de procedimentos de ovocentese deve ser restrita devido ao risco de lesões iatrogênicas que expõem o trato reprodutivo de aves fêmeas a infecções ascendentes que ofereçam risco de vida para os animais. Palavras chave: distúrbios reprodutivos, rapinantes, Micrastur, patologia aviária ABSTRACT This scientific report notifies the occurrence of chronic salpingitis in a captive Micrastur semitorquatus, ten years old. Salpingitis occured six months after an emergency procedure (ovocentesis). Due to the persistent apathy, difficulty breathing and an increase in abdominal volume, the bird was clinically evaluated in order to perform an exploratory laparotomy.