Project J-11/Task 15 IMPACTS of CUTS and REDUCTIONS in PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION FUNDING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiscal Monitor Report 1 Gary Public Transportation Corporation

Gary Public Transportation Corporation Report of the Fiscal Monitor Decembeer 29, 2009 Public Financial Management Two Logan Square 18th & Arch Streets, Suite 1600 Philadelphia, PA 19103 215 567 6100 www.pfm.com Gary Public Transportation Corporation Introduction In 2008 the State of Indiana enacted Public Law 146, establishing “circuit breaker tax credits” that cap local property taxes at a percentage of assessed value. Property taxes have recently been the source of 40 to 45 percent of the operating fund revenue for the Gary Public Transportation Corporation (GPTC). Based on analysis prepared for the State, the full implementation of the caps was projected to reduce the GPTC’s property tax revenues by approximately 31 percent from $3.89 million to $2.68 million in 2009 and then to $2.40 million in 2010.1 Because of the large gap between recent historical revenues and the amounts permitted by the cap, the City of Gary and several of its related units – the Gary-Chicago International Airport, the Gary Sanitary District, the Gary Storm Water Management District, and GPTC – petitioned the State of Indiana for relief from the caps for fiscal year 2009. The state body assigned to review such petitions, the Distressed Unit Appeals Board (DUAB), granted partial relief for all but the Sanitary District and directed the City and its related agencies to retain a fiscal monitor to “assist the petitioning units in rehabilitating their financial affairs in the near-term with the ultimate objective of alleviating the petitioning units of their distressed status.” Public Financial Management (PFM) was selected in a competitive process to serve as the fiscal monitor. -

'02 INDOT Part 1

2001 ANNUAL REPORT INDIANA PUBLIC TRANSIT STATE OF INDIANA Frank O’Bannon, Governor J. Bryan Nicol, Commissioner, Indiana Department of Transportation August 2001 Indiana Department of Transportation Public Transit Section 100 North Senate, Room N901 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 (317) 232-1483 This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of Indiana Department of Transportation, Public Transit Section. The preparation of this publication has been financed in part through grants from the United States Department of Transportation, under the provisions of Sections 5303 and 5311 of the Federal Transit Act, contract numbers IN-80-9007 and IN-18-6018. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Manufacturers names appear herein because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................ 1 Ridership Distribution by System........................................................................... 2 Total Vehicle Miles by System ................................................................................ 3 Transit System Operating Expenditures by Category/System................................ 4 Transit System Operating -

Northwest Indiana Regional Development Authority Return on Investment Analysis

Northwest Indiana Regional Development Authority Return on Investment Analysis November, 2012 RDA Return on Investment Analysis Table of Contents Introduction and Overview ...................................................................... 3 Methodology Description .......................................................................... 4 Project Leveraging ....................................................................................... 5 Shoreline Development .............................................................................. 6 Gary Chicago International Airport .................................................... 12 Surface Transportation ........................................................................... 17 Fiscal Impact ............................................................................................... 21 Total Economic Impact and ROI .......................................................... 22 2 RDA Return on Investment Analysis Overview and Summary The RDA was created in 2005 by the Indiana General Assembly to invest in the infrastructure and assets of Northwest Indiana [IC 36-7.5], and in so do- ing transform the economy and raise the quality of life for the region. The enabling statute listed four areas: 1) Assist in the development of the Gary Chicago International Airport. 2) Assist in the development of the Lake Michigan Shoreline. 3) Assist in the development of an integrated region-wide surface trans- portation system – encompassing both commuter rail and bus. 4) Assist in the development -

Of 65 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 6/11/13 CART & Transcription

Page 1 of 65 1 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 2 PURDUE CALUMET LIBRARY 3 HAMMOND, IN 4 JUNE 11, 2013 5 1-4 p.m. 6 7 8 CART SERVICES AND VERBATIM TRANSCRIPTION SERVICES 9 PROVIDED BY: 10 VOICE TO PRINT CAPTIONING, LLC 11 9800 Connecticut Drive 12 Crown Point, IN 46307 13 219-644-3220 14 www.voicetoprint.com 15 [email protected] 16 NIRPC ADA PUBLIC HEARING 6/11/13 CART & Transcription by Voice to Print Captioning Page 2 of 65 17 >> GAIL BARKER: Hello. My name is Gail Barker, the 18 Disability Coordinator at Purdue North Central. I will be 19 serving as the facilitator of this year's public hearing for the 20 Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission. I would like 21 to welcome those who are here at Purdue University Calumet for 22 our 2013 public hearing. I would also like to welcome those 23 that are watching on the Internet and those that are watching 24 from the site at LaPorte, Indiana also on the Internet. 25 NIRPC, as the agency is called, is a Metropolitan Planning 26 Organization that is responsible for regional transportation 27 planning in Lake, Porter and LaPorte Counties. 28 This hearing is being held as a result of a Class Action 29 ADA transportation lawsuit which was filed in 1997. ADA stands 30 for the Americans with Disabilities Act, which was enacted into 31 law in 1990. The lawsuit settlement, which was reached in 2006, 32 requires NIRPC to have an independent ADA review each year of 33 all its subgrantees; that is, all the public transit providers 34 for whom NIRPC provides monitoring and oversight. -

2008 Public Transportation Fact Book Part 3: Transit Agency and Urbanized Area Operating Statistics

2008 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION FACT BOOK PART 3: TRANSIT AGENCY AND URBANIZED AREA OPERATING STATISTICS June 2008 American Public Transportation Association 1666 K Street, N.W., Suite 1100 Washington, DC 20006 TELEPHONE: (202) 496-4800 EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.apta.com APTA's Vision Statement Be the leading force in advancing public transportation. APTA's Mission Statement To strengthen and improve public transportation, APTA serves and leads its diverse membership through advocacy, innovation, and information sharing. APTA's Policy on Diversity APTA recognizes the importance of diversity for conference topics and speakers and is committed to increasing the awareness of its membership on diversity issues. APTA welcomes ideas and suggestions on how to strengthen its efforts to meet these important diversity objectives. Prepared by John Neff, Senior Policy Researcher (202) 496-4812 [email protected] 2008 Public Transportation Fact Book Part 3: Transit Agency and Urbanized Area Operating Statistics American Public Transportation Association Washington, DC June 2008 Material from 2008 Public Transportation Fact Book, Part 3: Transit Agency and Urbanized Area Operating Statistics, may be quoted or reproduced, without obtaining the permission of the American Public Transportation Association. Suggested Identification: American Public Transportation Association: 2008 Public Transportation Fact Book, Part 3: Transit Agency and Urbanized Area Operating Statistics, Washington, DC, June, 2008. Data presented in this publication are based on data published in the National Transit Database. Washington: Federal Transit Administration, 2008, at http://www.ntdprogram.gov/ntdprogram/ About the Fact Book The American Public Transportation Association is a nonprofit international association of over 1,500 public and private member organizations including transit systems and commuter rail operators; planning, design, construction and finance firms; product and service providers; academic institutions, transit associations and state departments of transportation. -

2003 Indiana Public Transit Annual Report

2003 ANNUAL REPORT INDIANA PUBLIC TRANSIT STATE OF INDIANA Frank O’Bannon, Governor J. Bryan Nicol, Commissioner, Indiana Department of Transportation August 2003 Indiana Department of Transportation Public Transit Section 100 North Senate, Room N901 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 (317) 232-1482 This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the Indiana Department of Transportation, Public Transit Section. The preparation of this publication has been financed in part through grants from the United States Department of Transportation, under the provisions of the Federal Transit Act. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Manufacturers’ names appear herein because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. 2003 PUBLIC TRANSIT SYSTEMS IN INDIANA TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................ 1 Ridership Distribution by System........................................................................... 2 Total Vehicle Miles by System ................................................................................ 3 Transit System Operating Expenditures by Category/System................................ 4 Transit System Operating Revenues by Category/System..................................... -

Missed Opportunity: Transit and Jobs in Metropolitan America

METROPOLITAN INFRASTRUCTURE INITIATIVE SERIES and Metropolitan Opportunity Series Missed Opportunity: Transit and Jobs in Metropolitan America Adie Tomer, Elizabeth Kneebone, Robert Puentes, and Alan Berube Findings An analysis of data from 371 transit providers in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas reveals that: n Nearly 70 percent of large metropolitan residents live in neighborhoods with access to transit service of some kind. Transit coverage is highest in Western metro areas such as “ As states and Honolulu and Los Angeles, and lowest in Southern metro areas such as Chattanooga and Greenville. Regardless of region, residents of cities and lower-income neighborhoods have regions strive to better access to transit than residents of suburbs and middle/higher-income neighborhoods. n In neighborhoods covered by transit, morning rush hour service occurs about once every put Americans 10 minutes for the typical metropolitan commuter. In less than one quarter of large metro areas (23), however, is this typical service frequency, or “headway,” under 10 minutes. These back to work, include very large metro areas such as New york, Los Angeles, Houston, and Washington. Transit services city residents on average almost twice as frequently as suburban residents. poli cymakers n The typical metropolitan resident can reach about 30 percent of jobs in their metropoli- tan area via transit in 90 minutes. Job access differs considerably across metro areas, from should be careful 60 percent in Honolulu to just 7 percent in Palm Bay, reflecting variable transit coverage levels and service frequencies, and variable levels of employment and population decentralization. not to sever the Among very large metro areas, the share of jobs accessible via transit ranges from 37 percent in Washington and New york to 16 percent in Miami. -

Title VI Program Recertification Document

Title VI Program Recertification Document Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Section 601 Specific to Federal Transit Administration Programs March 16, 2017 Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission 6100 Southport Road Portage, Indiana 46368 Phone (219) 763.6060 Fax (219) 762.1653 e-mail: [email protected] 2017 Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission Title VI Program Certification Document Table of Contents NIRPC’S RESOLUTION ADOPTING TITLE VI PLAN IDENTIFICATION OF DESIGNATED RECIPIENT, DIRECT GRANTEE, AND SUBRECIPIENTS ............................................................................................................ 1 PART I. NIRPC GENERAL REPORTING REQUIREMENTS ................................ 3 1. REQUIREMENT TO PROVIDE AN ANNUAL TITLE VI CERTIFICATION AND ASSURANCES ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. REQUIREMENT TO DEVELOP TITLE VI COMPLAINT PROCEDURES .......................... 3 3. REQUIREMENT TO RECORD TITLE VI INVESTIGATIONS, COMPLAINTS, & LAWSUITS ........................................................................................................................... 3 4. REQUIREMENT TO PROVIDE MEANINGFUL ACCESS TO LIMITED ENGLISH PROFICIENCY (LEP) PERSONS........................................................................................... 3 5. REQUIREMENT TO NOTIFY BENEFICIARIES OF PROTECTION UNDER TITLE VI ....... 3 6. SUMMARY OF PUBLIC OUTREACH AND INVOLVEMENT ACTIVITIES ........................ -

Diagnostic-Feasibility Study of Wolf Lake, Cook County, Illinois, and Lake County, Indiana

Contract Report 604 Diagnostic-Feasibility Study of Wolf Lake, Cook County, Illinois, and Lake County, Indiana by Shun Dar Lin, Raman K. Raman, William C. Bogner, James A. Slowikowski, George S. Roadcap, and David L. Hullinger Prepared for the City of Hammond, Indiana Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, and Indiana Department of Environmental Management October 1996 Illinois State Water Survey Chemistry and Hydrology Divisions Champaign, Illinois A Division of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources Diagnostic-Feasibility Study of Wolf Lake, Cook County, Illinois, and Lake County, Indiana Shun Dar Lin, Raman K. Raman, William C. Bogner, James A. Slowikowski, George S. Roadcap, and David L. Hullinger Prepared for the City of Hammond, Indiana Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, and Indiana Department of Environmental Management October 1996 Funded under USEPA Grant # S995201-01-0. S995202 IDEM Contract # ARN92-5A. ARN92-4 IEPA Contract # SWC-2024 Illinois State Water Survey Chemistry and Hydrology Divisions Champaign, Illinois A Division of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources This report may be obtained from: The City of Hammond, Parks and Recreation Department, Hammond, IN; Indiana Department of Environmental Management, Nonpoint Source Section, Box 6015, Indianapolis, IN; Illinois Environmental Protection, Lake and Watershed Unit, Box 19276, Springfield, IL. The data collected during October 1992 through October 1993 may be obtained from IEPA, address as shown above. USEPA Region V Review of Wolf Lake Clean Lakes Diagnostic-Feasibility Study MACROPHYTE (LAKE WEED) CONTROL Most of those addressing this issue objected to the use of the compound 2-4D as a lake weed control measure because of feared side effects on other parts of the lake ecosystem. -

Appendix 6. Transit Systems Included in Database

Appendix 6. Transit Systems Included in Database Primary Metropolitan Area Transit System Akron, OH Metro Regional Transit Authority Akron, OH Portage Area Regional Transportation Authority Akron, OH Stark Area Regional Transit Authority Albany-Schenectady-Troy, NY Capital District Transportation Authority Albany-Schenectady-Troy, NY City of Mechanicville Transit Albany-Schenectady-Troy, NY Schoharie County Public Transportation Albuquerque, NM ABQ Ride Albuquerque, NM City of Belen Transit Albuquerque, NM Pueblo of Santa Ana Transit Albuquerque, NM Rail Runner (NMDOT) Albuquerque, NM Sandoval County Transit Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton, PA-NJ County of Carbon Transit Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton, PA-NJ Lehigh and Northampton Transportation Authority Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA Buckhead Community Improvement District Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA City of Canton Transit Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA Cobb Community Transit Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA Georgia Regional Transportation Authority Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA Gwinnett County Board of Commissioners Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority Augusta-Richmond County, GA-SC Augusta Richmond County Transit Department Augusta-Richmond County, GA-SC Best Friends Express (Lower Savannah COG) Austin-Round Rock, TX Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority Austin-Round Rock, TX Capitol Area Rural Transportation System Bakersfield, CA City of Arvin Transit Bakersfield, CA City of Delano Transit Bakersfield, CA Golden Empire -

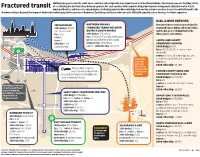

Fractured Transit at Coordinating Bus and Train Times Between Agencies, but Each Operates with a Separate Budget and Separate Management

Multiple bus agencies and the South Shore commuter railroad provide mass transit services in Northwest Indiana. There have been some fledgling efforts Fractured transit at coordinating bus and train times between agencies, but each operates with a separate budget and separate management. Many bus routes stop at municipal borders, and there is no system in place for buying transfers when switching from one bus system to another. A report recently delivered to the Northwest Indiana Regional Development Authority found merging the bus systems of Hammond, East Chicago and Gary could save up to $500,000 annually and set the stage for future expansion. DIAL-A-RIDE SERVICES CHICAGO DASH NORTHERN INDIANA Demand-response services operate just like 2009 budget: $111,193 COMMUTER TRANSPORTATION you would expect. Riders call ahead of time, (Oct. ’08 to current) DISTRICT (SOUTH SHORE) and the bus goes to them instead of the fare: $7.50 2008 budget: $38.2 million rider going to a bus station. routes: 1 fare: $3.80 to $7.45 one-way (Hammond to buses: 3 Millennium/South Bend to Millennium) SOUTH LAKE COUNTY ridership: 8,364 trains per day: 43 (weekday) COMMUNITY SERVICES (January to July) cars: 82 2008 ridership: 4.2 million 2008 budget: N.A. fare: $5.25 ($3.25 for seniors and * disabled) routes: Covers all townships in Lake V-Line service County except North and Calumet to the Dune buses: 8 Park South 2008 ridership: 13,500 Shore Station UPS pays PACE to operate operates solely seven daily nonstop buses from on Fridays and PORTER COUNTY AGING AND Gary and East Chicago to the Hodgkins UPS weekends. -

2000 Indiana Public Transit Annual Report

2000 ANNUAL REPORT INDIANA PUBLIC TRANSIT STATE OF INDIANA Frank O’Bannon, Governor J. Bryan Nicol, Commissioner, Indiana Department of Transportation August 2000 Indiana Department of Transportation Public Transit Section 100 North Senate, Room N901 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 (317) 232-1482 This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of Indiana Department of Transportation, Public Transit Section. The preparation of this publication has been financed in part through grants from the United States Department of Transportation, under the provisions of Sections 5303 and 5311 of the Federal Transit Act, contract numbers IN-80-9007 and IN-18-6018. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Manufacturers names appear herein because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. 2000 PUBLIC TRANSIT SYSTEMS IN INDIANA NICTD Michigan City East Chicago Elkhart Gary South Bend Hammond LaPorte LaPorte Goshen Porter Co. Lake Co. Co. Plymouth Starke Kosciusko Co. Co. Fort Wayne Jasper Pulaski Co. Newton Co. Co. Wabash White Cass Co. Co. Co. Brookston Boswell Lafayette/ Marion Kokomo West Lafayette Rossville Clarks Hill Muncie Madison Hillsboro Co. Anderson Waveland New Castle Richmond Indianapolis Union Terre Co. Haute Johnson Co. Franklin Co. Owen Co. Columbus Monroe Co. Dearborn Ripley Co. Bloomington Co. Seymour Ohio Bedford Co. Swittzerland Lawrence Co. Jefferson Co. Mitchell Co. Knox Washington Co. Orange Co. Clarksville Huntingburg Jeffersonville New Albany Harrison Co.