Platial Phenomenology and Environmental Composition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legacy of Futurism's Obsession with Speed in 1960S

Deus (ex) macchina: The Legacy of Futurism’s Obsession with Speed in 1960s Italy Adriana M. Baranello University of California, Los Angeles Il Futurismo si fonda sul completo rinnovamento della sensibilità umana avvenuto per effetto delle grandi scoperte scientifiche.1 In “Distruzione di sintassi; Imaginazione senza fili; Parole in lib- ertà” Marinetti echoes his call to arms that formally began with the “Fondazione e Manifesto del Futurismo” in 1909. Marinetti’s loud, attention grabbing, and at times violent agenda were to have a lasting impact on Italy. Not only does Marinetti’s ideology reecho throughout Futurism’s thirty-year lifespan, it reechoes throughout twentieth-century Italy. It is this lasting legacy, the marks that Marinetti left on Italy’s cultural subconscious, that I will examine in this paper. The cultural moment is the early Sixties, the height of Italy’s boom economico and a time of tremendous social shifts in Italy. This paper will look at two specific examples in which Marinetti’s social and aesthetic agenda, par- ticularly the nuova religione-morale della velocità, speed and the car as vital reinvigorating life forces.2 These obsessions were reflected and refocused half a century later, in sometimes subtly and sometimes surprisingly blatant ways. I will address, principally, Dino Risi’s 1962 film Il sorpasso, and Emilio Isgrò’s 1964 Poesia Volkswagen, two works from the height of the Boom. While the dash towards modernity began with the Futurists, the articulation of many of their ideas and projects would come to frui- tion in the Boom years. Leslie Paul Thiele writes that, “[b]reaking the chains of tradition, the Futurists assumed, would progressively liberate humankind, allowing it to claim its birthright as master of its world.”3 Futurism would not last to see this ideal realized, but parts of their agenda return continually, and especially in the post-war period. -

The Train and the Cosmos: Visionary Modernity

The Train and the Cosmos: Visionary Modernity Matilde Marcolli 2015 • Mythopoesis: the capacity of the human mind to spontaneously generate symbols, myths, metaphors, ::: • Psychology (especially C.G. Jung) showed that the human mind (especially the uncon- scious) continuously generates a complex lan- guage of symbols and mythology (archetypes) • Religion: any form of belief that involves the supernatural • Mythopoesis does not require Religion: it can be symbolic, metaphoric, lyrical, visionary, without any reference to anything supernatural • Visionary Modernity has its roots in the Anarcho-Socialist mythology of Progress (late 19th early 20th century) and is the best known example of non-religious mythopoesis 1 Part 1: Futurist Trains 2 Trains as powerful symbol of Modernity: • the world suddenly becomes connected at a global scale, like never before • trains collectively drive humankind into the new modern epoch • connected to another powerful symbol: electricity • importance of the train symbolism in the anarcho-socialist philosophy of late 19th and early 20th century (Italian and Russian Futurism avant garde) 3 Rozanova, Composition with Train, 1910 4 Russolo, Dynamism of a Train, 1912 5 From a popular Italian song: Francesco Guccini \La Locomotiva" ... sembrava il treno anch'esso un mito di progesso lanciato sopra i continenti; e la locomotiva sembrava fosse un mostro strano che l'uomo dominava con il pensiero e con la mano: ruggendo si lasciava indietro distanze che sembravano infinite; sembrava avesse dentro un potere tremendo, la stessa forza della dinamite... ...the train itself looked like a myth of progress, launched over the continents; and the locomo- tive looked like a strange monster, that man could tame with thought and with the hand: roaring it would leave behind seemingly enor- mous distances; it seemed to contain an enor- mous might, the power of dynamite itself.. -

Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D) Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, PROPAGANDA, MONTAGE: Soviet Avant-Garde “We are all primitives of the 20th century” – Ivan Kliun, 1916 UNOVIS members’ aims include the “study of the system of Suprematist projection and the designing of blueprints and plans in accordance with it; ruling off the earth’s expanse into squares, giving each energy cell its place in the overall scheme; organization and accommodation on the earth’s surface of all its intrinsic elements, charting those points and lines out of which the forms of Suprematism will ascend and slip into space.” — Ilya Chashnik , 1921 I. Making “Modern Man” A. Kasimir Malevich – Suprematism 1) Suprematism begins ca. 1913, influenced by Cubo-Futurism 2) Suprematism officially launched, 1915 – manifesto and exhibition titled “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd. B. El (Elazar) Lissitzky 1) “Proun” as utopia 2) Types, and the new modern man C. Modern Woman? 1) Sonia Terk Delaunay in Paris a) “Orphism” or “organic Cubism” 1911 b) “Simultaneous” clothing, ceramics, textiles, cars 1913-20s 2) Natalia Goncharova, “Rayonism” 3) Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova stage designs II. Monuments without Beards -- Vladimir Tatlin A. Constructivism (developed in parallel with Suprematism as sculptural variant) B. Productivism (the tweaking of “l’art pour l’art” to be more socialist) C. Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower), 1921 III. Collapse of the Avant-Garde? A. 1937 Paris Exposition, 1937 Entartete Kunst, 1939 Popular Front B. -

Strategies of Defending Astrology: a Continuing Tradition

Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition by Teri Gee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Teri Gee (2012) Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition Teri Gee Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Astrology is a science which has had an uncertain status throughout its history, from its beginnings in Greco-Roman Antiquity to the medieval Islamic world and Christian Europe which led to frequent debates about its validity and what kind of a place it should have, if any, in various cultures. Written in the second century A.D., Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos is not the earliest surviving text on astrology. However, the complex defense given in the Tetrabiblos will be treated as an important starting point because it changed the way astrology would be justified in Christian and Muslim works and the influence Ptolemy’s presentation had on later works represents a continuation of the method introduced in the Tetrabiblos. Abû Ma‘shar’s Kitâb al- Madkhal al-kabîr ilâ ‘ilm ahk. âm al-nujûm, written in the ninth century, was the most thorough surviving defense from the Islamic world. Roger Bacon’s Opus maius, although not focused solely on advocating astrology, nevertheless, does contain a significant defense which has definite links to the works of both Abû Ma‘shar and Ptolemy. As such, he demonstrates another stage in the development of astrology. -

PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science, UO Philosophy Dept, Winter 2018

1 PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science, UO Philosophy Dept, Winter 2018 Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Benjamin Franklin,Watson & Crick, Rosalind Franklin, Galileo Galilei, Dr. Linus Pauling, William Crawford Eddy, James Watt Maria Goeppert-Mayer, Charles Darwin, James Clerk Maxwell, Archimedes, Lise Meitner, Sigmund Freud, Irène Joliot-Curie Gregor Johann Mendel,Chien-Shiung Wu,Barbara McClintock, Neil DeGrasse Tyson. All Contents ©2017 Photo Researchers, Inc., 307 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY , 10016 212-758-3420 800-833- 9033 Science Source® is a registered trademark of Photo Researchers, Inc. / 2 PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science, UO Philosophy Dept, Winter 2018 Course Data PHIL 339 Intro Phil of Science >2 4.00 cr. Grading Options: Optional for all students Instructor: Prof. N. Zack, Office: 239 SCH Phone: (541) 346-1547 Office Hours: WTh -2-3 See CRN for CommentsPrereqs/Comments: Prereq: one philosophy course (waiver available) *Note: This is a 2-hr course twice a week and discussion is built in. There will breaks and variations in subject matter to keep it interesting. OVERVIEW/DESCRIPTION (See also APPENDICES A-D AFTER SYLLABUS) Philosophy of Science is unique to philosophy. It raises questions about facts, theories, reality, explanation, and truth not often addressed by scientists or other humanistic scholars. This course will provide the basics of Philosophy of Science with concrete examples as science now applies to contemporary subjects such as Climate Change, Feminism, and Race. Students will have an opportunity to choose their own branches of inquiry for end-of-term reports. Work will consist of reading, discussion, and 4 3-page papers. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

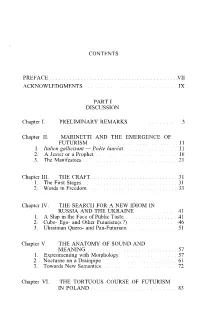

Contents Preface Vii Acknowledgments Ix Part I

CONTENTS PREFACE VII ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX PART I DISCUSSION Chapter I. PRELIMINARY REMARKS 3 Chapter II. MARINETTI AND THE EMERGENCE OF FUTURISM 11 1. Italien gallicisant — Poète lauréat 11 2. A Jester or a Prophet 16 3. The Manifestoes 21 Chapter III. THE CRAFT 31 1. The First Stages 31 2. Words in Freedom 33 Chapter IV. THE SEARCH FOR A NEW IDIOM IN RUSSIA AND THE UKRAINE 41 1. A Slap in the Face of Public Taste 41 2. Cubo- Ego- and Other Futurism(s ?) 46 3. Ukrainian Quero- and Pan-Futurism 51 Chapter V. THE ANATOMY OF SOUND AND MEANING 57 1. Experimenting with Morphology 57 2. Nocturne on a Drainpipe 61 3. Towards New Semantics 72 Chapter VI. THE TORTUOUS COURSE OF FUTURISM IN POLAND 83 XII FUTURISM IN MODERN POETRY Chapter VII. THE FURTHER EXPANSION OF THE FUTURIST IDEAS 97 1. Futurism in Czech and Slovak Poetry 97 2. Slovenia 102 3. Spain and Portugal 107 4. Brazil 109 Chapter VIII. CONCLUSION 117 PART II A SELECTION OF FUTURIST POETRY I. ITALY 125 A. FREE VERSE 125 Libero Altomare Canto futurista 126 A Futurist Song 127 A un aviatore 130 To an Aviator 131 Enrico Cardile Ode alia violenza 134 Ode to Violence 135 Enrico Cavacchioli Fuga in aeroplano 142 Flight in an Aeroplane 143 Auro D'Alba II piccolo re 146 The Little King 147 Luciano Folgore L'Elettricità 150 Electricity 151 F.T. Marinetti À l'automobile de course 154 To a Racing Car 155 Armando Mazza A Venezia 158 To Venice 159 Aldo Palazzeschi E lasciatemi divertire 164 And Let Me Have Fun 165 B. -

Claudius Ptolemy: Tetrabiblos

CLAUDIUS PTOLEMY: TETRABIBLOS OR THE QUADRIPARTITE MATHEMATICAL TREATISE FOUR BOOKS OF THE INFLUENCE OF THE STARS TRANSLATED FROM THE GREEK PARAPHRASE OF PROCLUS BY J. M. ASHMAND London, Davis and Dickson [1822] This version courtesy of http://www.classicalastrologer.com/ Revised 04-09-2008 Foreword It is fair to say that Claudius Ptolemy made the greatest single contribution to the preservation and transmission of astrological and astronomical knowledge of the Classical and Ancient world. No study of Traditional Astrology can ignore the importance and influence of this encyclopaedic work. It speaks not only of the stars, but of a distinct cosmology that prevailed until the 18th century. It is easy to jeer at someone who thinks the earth is the cosmic centre and refers to it as existing in a sublunary sphere. However, our current knowledge tells us that the universe is infinite. It seems to me that in an infinite universe, any given point must be the centre. Sometimes scientists are not so scientific. The fact is, it still applies to us for our purposes and even the most rational among us do not refer to sunrise as earth set. It practical terms, the Moon does have the most immediate effect on the Earth which is, after all, our point of reference. She turns the tides, influences vegetative growth and the menstrual cycle. What has become known as the Ptolemaic Universe, consisted of concentric circles emanating from Earth to the eighth sphere of the Fixed Stars, also known as the Empyrean. This cosmology is as spiritual as it is physical. -

Reel-To-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

Reel-to-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alan Campbell, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Ryan T. Skinner, Advisor Danielle Fosler-Lussier Barry Shank 1 Copyrighted by Matthew Alan Campbell 2019 2 Abstract For members of the United States Armed Forces, communicating with one’s loved ones has taken many forms, employing every available medium from the telegraph to Twitter. My project examines one particular mode of exchange—“audio letters”—during one of the US military’s most trying and traumatic periods, the Vietnam War. By making possible the transmission of the embodied voice, experiential soundscapes, and personalized popular culture to zones generally restricted to purely written or typed correspondence, these recordings enabled forms of romantic, platonic, and familial intimacy beyond that of the written word. More specifically, I will examine the impact of war and its sustained separations on the creative and improvisational use of prosthetic culture, technologies that allow human beings to extend and manipulate aspects of their person beyond their own bodies. Reel-to-reel was part of a constellation of amateur recording technologies, including Super 8mm film, Polaroid photography, and the Kodak slide carousel, which, for the first time, allowed average Americans the ability to capture, reify, and share their life experiences in multiple modalities, resulting in the construction of a set of media-inflected subjectivities (at home) and intimate intersubjectivities developed across spatiotemporal divides. -

As Above, So Below. Astrology and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century New Spain

Department of History and Civilization As Above, So Below. Astrology and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century New Spain Ana Avalos Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, February 2007 EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE Department of History and Civilization As Above, So Below. Astrology and the Inquisition in Seventeenth-Century New Spain Ana Avalos Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board: Prof. Peter Becker, Johannes-Kepler-Universität Linz Institut für Neuere Geschichte und Zeitgeschichte (Supervisor) Prof. Víctor Navarro Brotons, Istituto de Historia de la Ciencia y Documentación “López Piñero” (External Supervisor) Prof. Antonella Romano, European University Institute Prof. Perla Chinchilla Pawling, Universidad Iberoamericana © 2007, Ana Avalos No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author A Bernardo y Lupita. ‘That which is above is like that which is below and that which is below is like that which is above, to achieve the wonders of the one thing…’ Hermes Trismegistus Contents Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations 5 Introduction 6 1. The place of astrology in the history of the Scientific Revolution 7 2. The place of astrology in the history of the Inquisition 13 3. Astrology and the Inquisition in seventeenth-century New Spain 17 Chapter 1. Early Modern Astrology: a Question of Discipline? 24 1.1. The astrological tradition 27 1.2. Astrological practice 32 1.3. Astrology and medicine in the New World 41 1.4. -

The Humanities in Deconstruction: Raising the Question of the Post-Colonial University

ACCESS: CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN EDUCATION 2007, VOL. 26, NO. 1, 1–10 The humanities in deconstruction: Raising the question of the post-colonial university Michael A. Peters University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign ABSTRACT Derrida is, perhaps, the foremost philosopher of the humanities and of its place in the university. Over the long period of his career he has been concerned with the fate, status, place and contribution of the humanities. Through his deconstructive readings and writings he has done much not only to reinvent the Western tradition by attending closely to those texts which constitute it but also he has redefined its procedures and protocols, questioning and commenting upon the relationship between commentary and interpretation, the practice of quotation, the delimitation of a work and its singularity, its signature, and its context – the whole form of life of literary culture, together with textual practices and conventions that shape it. From his very early work he has occupied a marginal in-between space – simultaneously, textual, literary, philosophical, and political – a space that permitted him a freedom to question, to speculate and to draw new limits to humanitas. Derrida has demonstrated his power to reconceptualise and to reimagine the humanities in the space of the contemporary university. This paper discusses Derrida’s tasks for the new humanities (Trifonas & Peters, 2005). 1. Fundamentalisms and the need for a deconstructive humanities An appreciation of Derrida’s work can shed light on the growth and clash