Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ontario, Canada

ONTARIO, CANADA Featuring Niagara Falls July 19 - 30, 2019 Everyone knows Ontario for the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, but did you know that around 40% of Canada’s population lives in Ontario. Did you also know that Ontario is larger than France and Spain combined and it has over 250,000 lakes, which contains a fifth of the planet’s fresh water! Join us as we explore this amazing Canadian province and all it has to offer. Niagara Falls at Dusk DAY 1: Marshall, MN to Davenport, IA Relax and enjoy the scenery aboard your luxury motor coach as you make your way to Davenport, IA today. BW Plus Steeplegate Inn DAY 2: Davenport, IA to Windsor, Ontario Today will be a travel day as you journey to Ontario. Enjoy the stunning scenery of Ilinois, Indiana, and Michigan before crossing the border into Canada. Holiday Inn Express * Breakfast Included DAY 3: Windsor, Ontario to Niagara Falls, Ontario As you continue on to Niagara Falls, Ontario today, you’ll stop in Hamilton for a guided tour of the Dundurn Castle and Gardens. Your costumed guide will take you through the 40-room Italian-style villa that was built in the 1830’s by Sir Allan Napier MacNab, a railway magnate, lawyer and Premier of the United Canadas. You’ll hear stories about the family that lived there and the people who worked there to support their affluent lifestyle. At dusk, you’ll view Niagara Falls as it is transformed into an incredible, multi-colored water and light masterpiece. Comfort Inn Fallsview * Breakfast & Dinner Included DAY 4: Niagara Falls, Ontario to Toronto, Ontario Your day begins with a Niagara Falls guided tour. -

Of the American Falls at Niagara 1I I Preservation and Enhancement of the American Falls at Niagara

of the American Falls at Niagara 1I I Preservation and Enhancement of the American Falls at Niagara Property of t';e Internztio~al J5it-t; Cr?rn:n es-un DO NOT' RECda'dg Appendix G - Environmental Considerations Final Report to the International Joint Commission by the American Falls International Board June -1974 PRESERVATION AND ENHANCEMENT OF AMERICAN FALLS APPENDIX. G .ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph Page CHAPTER G 1 .INTRODUCTION G1 CHAPTER G2 .ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING . NIAGARA RESERVATION AND SURROUNDING REGION GENERAL DESCRIPTION ............................................................... PHYSICAL ELEMENTS ..................................................................... GENERAL .................................................................................... STRATIGRAPHY ......................................................................... SOILS ............................................................................................ WATER QUALITY ........................................................................ CLIMATE INVENTORY ................................................................... CLIMATE ....................................................................................... AIR QUALITY .............................................................................. BIOLOGICAL ELEMENTS ................................................................ TERRESTRIAL VEGETATION ..................................................... TERRESTRIAL WILDLIFE ......................................................... -

Doing Niagara Falls If You're Stuck on the American Side

Meiqianbao/ Shutterstock Doing Niagara Falls If You're Stuck on the American Side By Jason Cochran The legendary Niagara Falls, one of the greatest natural attractions in North America, straddles the border between Ontario, Canada, and New York State. In an ideal tourism situation, you'd be able to drive or stroll across the Rainbow International Bridge to enjoy the view from both banks of the Niagara River. But sometimes you just can't get over the border. Maybe you don't have enough time. Maybe your legal status won't allow it. Or maybe you happen to be living through a once-in-a-lifetime global pandemic that has sealed national borders. It's all good! If you're restricted to the U.S. side, you won't find yourself over a barrel. There's plenty to do. In fact, some of the best activities in the Niagara Falls area are on the American side. Pictured above: Terrapin Point, at right, juts into the eastern side of the Falls from Niagara Falls State Park in New York State. Niagara Falls State Park Niagara Falls State Park If we're being honest, the Canadian side has richer options for quality lodging and tourist amenities, although the stuff on that riverbank tends toward cheesy honky-tonk. New York's territory beside the Falls, on the other hand, has been preserved from development since the 1880s. In fact, the area is now the oldest state park in the United States. The more-than-400-acre Niagara Falls State Park, which is separated from the core of town by a breakaway river, is speckled with whitewater-spanning bridges, river islands, curving walkways, and native animals. -

Waterfalls: Forms, Distribution, Processes and Rates of Recession

QUAESTIONES GEOGRAPHICAE 39(1) • 2020 WATERFALLS: FORMS, DISTRIBUTION, PROCESSES AND RATES OF RECESSION ANDREW S. GOUDIE School of Geography, Centre for the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom Manuscript received: December 15, 2019 Revised version: February 2, 2020 GOUDIE A. S., 2020. Waterfalls: forms, distribution, processes and rates of recession. Quaestiones Geographicae 39(1), Bo- gucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Poznań, pp. 59–77. 8 figs, 3 tables. ABSTRACT: A waterfall is a very steep (commonly nearly vertical) fall of some magnitude in a river course. Waterfalls are widespread fluvial landforms that have been described from many parts of the world. Thirty-eight World Heritage Properties include waterfalls in their designation. In addition, some waterfalls are actual or potential geomorphosites. Waterfalls occur in almost all climatic environments, though they are particularly common in formerly glaciated areas. They occur on a huge diversity of rock types, although in general, they do not form persistent or large falls on soft or unconsolidated rocks. Waterfalls also occur in a wide range of geomorphological settings: glaciated areas, areas of ac- tive tectonism, areas of sea-cliff retreat and sea-level change, great escarpments on passive margins, basins with river capture, rifted and faulted areas and areas that have been subjected to megaflooding. Multiple processes account for waterfall retreat and varying rates of recession. Although the greatest interest has been in rates of waterfall recession, there are examples of waterfalls that prograde as a result of tufa deposition. KEY WORDS: waterfalls, caprock, knickpoints, plunge pools, tufa Corresponding author: Andrew Goudie, [email protected] Introduction distribution and rates of retreat. -

Downtown Neighborhood City of Niagara Falls: Phase I

Intensive Level Survey Historic Resources – Downtown Neighborhood City of Niagara Falls: Phase I 3.0 Historical Overview This section provides a narrative history of the City of Niagara Falls with specific emphasis on the Downtown neighborhood. The overview addresses significant trends and themes associated with the city’s historic context. The Downtown neighborhood’s period of significance is identified and examined in this chapter. Martin Wachadlo, architectural historian, conducted the background historic research. 3.1 Niagara County: Physiology and Geology Figure 3-1. Niagara Falls, Niagara Falls, New York Niagara County borders the southern shore of Lake Ontario in the extreme northwestern corner of New York State, and occupies part of the Huron and Ontario Plains. The Ontario Plain comprises part of Lake Ontario to the foot of the Niagara Escarpment1, and the Huron plain extends from the crest of the escarpment southward beyond the county line. The Niagara Escarpment begins in Watertown, New York, USA and extends westerly along the Manitoulin Island in the Province of Ontario, Canada. The escarpment continues through Wisconsin and Illinois. With geological material measuring 64-ft thick, the stratigraphy at Niagara Falls provides a glimpse into the overall rock types comprising the Niagara Escarpment (Figure 3-1). The top layer is Lockport Dolomite, a hard rock referred to as the "Lower Silurian Group." Below the top layer is Rochester Shale, which is much softer and wears away easily with the effects of erosion. Under the shale are harder strata of limestone and dolostone known as the "Clinton Group." Below the harder strata is Grimsby sandstone. -

September Gsat 03

GSA 2007 Annual Meeting Technical Program, p. 20 VOL. 17, No. 9 A PublicatioN Of the GeoloGical SoCiety Of AMeRica SePteMbeR 2007 Blue Nile incision on the Ethiopian Plateau: Pulsed plateau growth, Pliocene uplift, and hominin evolution Section Meetings Cordilleran and Rocky Mountain Joint Meeting, p. 49 Northeastern Section Meeting, p. 52 South-Central Section Meeting, p. 53 Penrose Conference Report, p. 55 Field Forum Report, p. 57 VoluMe 17, NuMbeR 9 SePteMbeR 2007 Cover: image (~40 × 20 km): 3-D perspective view (vertical exaggeration 5) of part of the Gorge of the Nile on the northwestern ethiopian Plateau (south of Mount Choke) generated by draping advanced spaceborne thermal emission and reflection radiometer (ASTER) image (7-3-1) over 15-m horizontal resolution ASTER digital elevation GSA TODAY publishes news and information for more than 20,000 GSA members and subscribing libraries. GSA Today model. trunk river (blue Nile) is flowing toward the lead science articles should present the results of exciting new viewer. Photo (~10 × 7 km): Section from the same research or summarize and synthesize important problems area, where the blue Nile deeply dissects Mesozoic or issues, and they must be understandable to all in the sandstones. See “blue Nile incision on the ethiopian earth science community. Submit manuscripts to science Plateau: Pulsed plateau growth, Pliocene uplift, and editors Stephen Johnston, [email protected], or David Fastovsky, hominin evolution,” by Gani et al., p. 4–11. [email protected]. GSA TODAY (ISSN 1052-5173 USPS 0456-530) is published 11 times per year, monthly, with a combined April/May issue, by SCIENCE ARTICLE The Geological Society of America, Inc., with offices at 3300 Penrose Place, Boulder, Colorado. -

Souvenir View Book of Niagara Falls.

SoiwenirWiew Bo6l{ of Kiiagara Falls .ov^ \ 273743 ^- LIBRARY BROCK UNIV£RSiT)t " " ' ^ ' '—T'ffiSg'?^?''*^ 'i^S^j Niagara Falls, New York lAGARA FALLS, the greatest natural wonder in the world, is sitiiated. about twenty-two miles from the beginning of the Niagara River at Lake Elrie and fourteen miles from where this river empties into Lake Onteirio. It is divided into two distinct falls known as th<5 American and Horseshoe Falls, by Goat Island, which is now a gov- ernment reservation. The American Fall is 1 67 feet high, 1 060 feet wide. Horseshoe Fall is 158 feet high and 3010 feet wide. It is estimated that 1 5,000,000 cubic feet of water pass over both falls each minute. The total fall of the Niagara River, from its source at Lake Erie to Lake Ontario is 336 feet, as follows: From Lake Erie to the brink of the faUs, 70 feet, at the falls. 161 feet, from the falls to Lake Ontario 105 feet. About twenty-two miles south of Niagara Falls, where the Niagara River leaves Lake Elrie, is located the city of BufiFalo. a prosperous, rapidly growing city, with a population of about 600,000. ns KSViiS^fatf^iiinSvuB'Si till ^ CROSSING THE GREAT WHIRLPOOL, NIAGARA FALLS, CANADA. AERO CABLE CAR Kapids mi.^beWwth^Fa^^^^ Tt^S?i« which oj^tf rTrf car span the .or^e above the Whirlpool 3 becomes a seathing. leaping, maddened torrent oi loan. tremendous flow of water is oonfined to a narrow space and wat«r. as', ^^^^^TwS J. -

Fixing Niagara Falls

Fixing Niagara Falls Environment, Energy, and Engineers at the World’s Most Famous Waterfall !"#$%& '"()"*&"#% +,*%-,*. /0 1*"%2% 30## 4e Nature | History | Society series is devoted to the publication of high- quality scholarship in environmental history and allied 5elds. Its broad compass is signalled by its title: nature because it takes the natural world seriously; history because it aims to foster work that has temporal depth; and society because its essential concern is with the interface between nature and society, broadly conceived. 4e series is avowedly interdisciplinary and is open to the work of anthropologists, ecologists, historians, geographers, literary scholars, political scientists, sociologists, and others whose interests resonate with its mandate. It o6ers a timely outlet for lively, innovative, and well-written work on the interaction of people and nature through time in North America. General Editor: Graeme Wynn, University of British Columbia A list of titles in the series appears at the end of the book. Contents List of Illustrations / viii Foreword: Iconic Falls, Contrived Landscapes, and Tantalizing Opportunities / xi Graeme Wynn Acknowledgments / xxvii List of Abbreviations / xxxi Introduction: Characterizing Niagara / 7 8 Harnessing Niagara: Developments up to the Twentieth Century / 89 : Saving Niagara: Innovation and Change in the Early Twentieth Century / 7; 7 Negotiating Niagara: Environmental Diplomacy and the 8;<= Treaty / >7 ? Empowering Niagara: Diversions and Generating Stations / ;= < Disguising Niagara: 4e Horseshoe Falls Waterscape / 878 > Preserving Niagara: 4e American Falls Campaign / 8>9 Conclusion: Fabricating Niagara / 8;9 Notes / :8= Bibliography / :98 Index / :;8 @#A*,.B(A$,# Characterizing Niagara If you wish to see this place in its grandeur, hasten. -

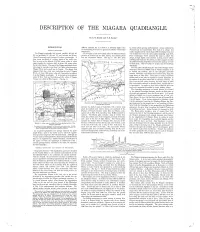

Description of the Niagara Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE NIAGARA QUADRANGLE. By E. M. Kindle and F. B. Taylor.a INTRODUCTION. different altitudes, but as a whole it is distinctly higher than by broad valleys opening northwestward. Across northwestern GENERAL RELATIONS. the surrounding areas and is in general bounded by well-marked Pennsylvania and southwestern New York it is abrupt and escarpments. i nearly straight and its crest is about 1000 feet higher than, and The Niagara quadrangle lies between parallels 43° and 43° In the region of the lower Great Lakes the Glaciated Plains 4 or 5 miles back from the narrow plain bordering Lake Erie. 30' and meridians 78° 30' and 79° and includes the Wilson, province is divided into the Erie, Huron, and Ontario plains From Cattaraugus Creek eastward the scarp is rather less Olcott, Tonawanda, and Lockport 15-minute quadrangles. It and the Laurentian Plateau. (See fig. 2.) The Erie plain abrupt, though higher, and is broken by deep, narrow valleys thus covers one-fourth of a square degree of the earth's sur extending well back into the plateau, so that it appears as a line face, an area, in that latitude, of 870.9 square miles, of which of northward-facing steep-sided promontories jutting out into approximately the northern third, or about 293 square miles, the Erie plain. East of Auburn it merges into the Onondaga lies in Lake Ontario. The map of the Niagara quadrangle shows escarpment. also along its west side a strip from 3 to 6 miles wide comprising The Erie plain extends along the base of the Portage escarp Niagara River and a small area in Canada. -

Niagara Falls Already Ruined 119

- : ::::;::::_ Niagara Falls Already' Ruined Concessions for Power Plants Already Granted Sufficient to Use All the Water T h e R emedy By ALTON D. ADAMS 1 1 Consulting Hydraulic Engineer IAGARA FALLS are already In the first place it is to be considered ruined! Already enough water that the American Falls are in much N rights have been granted by New more imminent danger than the Cana York State and Canada to divert dian. The pipe line, canal, and tunnels all the water which now, falling over that already pierce the cliffs between the both the American and the Canadian upper river and Niagara Gorge, are large fa ll s, makes the great cataract one of the enough in themselves to carry twice the natural wonders of the world. If the amount of water which runs over the capitalists and promoters who now hold American Falls. And the depth of water franchises were all to establish plants, above the brink of these falls is only a the entire fl ow of N iagara river would small fraction of the depth above the be diverted into underground channels; Canadian falls. It is therefore possible and the mighty cliff over which the tor for the American Falls to run entirelv rent now pours in resistless grandeur dry, while an imposing depth of wate.r would be left rugged and bald and dry. still runs over the Horseshoe on the That is th e situation. What, now is Canadian sid e. the rem eel y ? One suggestion looking towards the HEAD OF THE NIAGARA RAPIDS. -

Factors Influencing the Recession Rate of Niagara Falls Since the 19Th Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Tsukuba Repository Factors influencing the recession rate of Niagara Falls since the 19th century 著者 Hayakawa Yuichi S., Matsukura Yukinori journal or Geomorphology publication title volume 110 number 3-4 page range 212-216 year 2009-09-15 権利 (C) 2009 Elsevier B.V. URL http://hdl.handle.net/2241/103715 doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.04.011 1 Factors influencing the recession rate of Niagara Falls since the 19th century 2 Yuichi S. Hayakawa a,* and Yukinori Matsukura a 3 a Geoenvironmental Sciences, Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1 4 Ten-nodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8572, Japan 5 6 7 * Corresponding author. Tel: +81-29-853-5691; Fax: +81-29-853-4460 8 E-mail address: [email protected] (Y.S. Hayakawa) 1 9 Abstract 10 11 The rate of recession of Niagara Falls (Horseshoe and American Falls) in northeastern 12 North America has been documented since the 19th century; it shows a decreasing trend from ca. 13 1 m y-1 a century ago to ca. 0.1 m y-1 at present. Reduction of the flow volume in the Niagara 14 River due to diversion into bypassing hydroelectric schemes has often been taken to be the 15 factor responsible, but other factors such as changes in the waterfall shape could play a role and 16 call for a quantitative study. Here, we examine the effect of physical factors on the historically 17 varying recession rates of Niagara Falls, using an empirical equation which has previously been 18 proposed based on a non-dimensional multiparametric model which incorporates flow volume, 19 waterfall shape and bedrock strength. -

What Future for Niagara Falls?

SHAILER S. PHILBRICK Department of Geological Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14850 What Future for Niagara Falls? ABSTRACT Horseshoes and may be so slow in recession proposed increased diversion of water from as to be a quasi-stationary falls, without the falls for production of hydroelectric The recession of Niagara Falls up the immediate change in the level of Lake Erie. power on both the American and Canadian thalweg of Niagara River will be marked by sides of the river required a series of five major events. Event No. 1: The INTRODUCTION engineering studies of the falls, the Niagara Horseshoe Falls will first lower the level of The concept of retreat of Niagara Falls River, and the water yield of the Upper the Chippawa-Grass Island Pool below the from somewhere near the old landing in the Great Lakes. The latter confirmed one of the bottom of the American Channel and Niagara River at the foot of the Niagara fundamental facts of the Niagara River: its unwater the American Falls. The level of Escarpment near Queenston, Ontario, to flow is nearly uniform because of the great Lake Erie may be lowered a few feet at this about its present location was held by some headwater storage capacity of the upper time. The falls will split into two Horseshoes people 186 yr ago. Capt. Enys (1886, p. lakes. Detailed surveys, hydraulic-model at Navy Island, and the Lockport Gorge, the ccxxxii), a Canadian of the 29th Regiment, studies, plans for the preservation and extension of the Upper Great Gorge in wrote, under the date of July 19, 1787, enhancement of Niagara Falls, and interna- the Lockport Dolomite, will fork into two "Among those who favor this opinion is a tional agreement on the quantities of water gorges; the right hand one in the Tona- Mr.