Rethinking Prison Sex: Self Expression and Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© 2014 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Original U.S. Government Works

Dignam, Brett 8/7/2014 For Educational Use Only PUNISHING PREGNANCY: RACE, INCARCERATION, AND..., 100 Cal. L. Rev. 1239 100 Cal. L. Rev. 1239 California Law Review October, 2012 Article PUNISHING PREGNANCY: RACE, INCARCERATION, AND THE SHACKLING OF PREGNANT PRISONERS a1 Priscilla A. Ocen a2 Copyright (c) 2012 California Law Review, Inc., a California Nonprofit Corporation; Priscilla A. Ocen The shackling of pregnant prisoners during labor and childbirth is endemic within women's penal institutions in the United States. This Article investigates the factors that account for the pervasiveness of this practice and suggests doctrinal innovations that may be leveraged to prevent its continuation. At a general level, this Article asserts that we cannot understand the persistence of the shackling of female prisoners without understanding how historical constructions of race and gender operate structurally to both motivate and mask its use. More specifically, this Article contends that while shackling affects female prisoners of all races today, the persistent practice attaches to Black women in particular through the historical devaluation, regulation, and punishment of their exercise of reproductive capacity in three contexts: slavery, convict leasing, and chain gangs in the South. The regulation and punishment of Black women within these oppressive systems reinforced and reproduced stereotypes of these women as deviant and dangerous. In turn, as Southern penal practices proliferated in the United States and Black women became a significant percentage of the female *1240 prison population, these images began to animate harsh practices against all female prisoners. Moreover, this Article asserts that current jurisprudence concerning the Eighth Amendment, the primary constitutional vehicle for challenging conditions of confinement, such as shackling, is insufficient to combat racialized practices at the structural level. -

Inmate-On-Inmate Prison Rape of Adult Males

INMATE-ON-INMATE RAPE OF ADULT MALES IN PRISON Approved: Date: May 15, 2006 Advisor INMATE-ON-INMATE RAPE OF ADULT MALES IN PRISON A Seminar Paper Presented to the Graduate Faculty University of Wisconsin-Platteville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Criminal Justice Teresa Panek Ives May 2006 ii Acknowledgements As with any endeavor, it is not the destination as much as it is the journey. First, I must acknowledge all the victims of inmate-on-inmate prison rape. This paper would not be possible if not for the personal sacrifices and emotional support of my parents, Juzef and Bronislawa, and my husband, Paul. I would also like to thank my sister, Kathy, and my two dearest friends, Maria and Lydia, for their loving hearts. I would like to thank my graduate advisor, Dr. Cheryl Banachowski-Fuller, for helping me navigate through the intricacies of the criminal justice program, and my paper advisor, Dr. Susan Hilal, for her constructive guidance and patience. I would also like to thank all my instructors in the criminal justice program for sharing their knowledge and for pushing me to excel. I would like to thank Gary Apperson for his “virtual” friendship, encouragement, and for engaging me in insightful scholarly commentary, and Jeremy Brown for introducing me to the program. Lastly, but, most importantly, I must thank God for all my countless blessings. iii Abstract Inmate-on-Inmate Rape of Adult Males in Prison Teresa Panek Ives Under the Supervision of Dr. Susan Hilal Statement of the Problem Rape of male inmates is a risk that is associated with imprisonment. -

Benevolent Feminism and the Gendering of Criminality: Historical and Ideological Constructions of US Women's Prisons

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2020 Benevolent Feminism and the Gendering of Criminality: Historical and Ideological Constructions of US Women's Prisons Emma Stammen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Benevolent Feminism and the Gendering of Criminality: Historical and Ideological Constructions of US Women’s Prisons By Emma Stammen Submitted to Scripps College in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts Professor Piya Chatterjee Professor Jih-Fei Cheng December 13, 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to Professor Piya Chatterjee for advising me throughout my brainstorming, researching, and writing processes, and for her thoughtful and constructive feedback. Professor Chatterjee took the time to set up calls with me during the summer while I was researching in New York, and met with me consistently throughout the semester to make timelines, talk through ideas, and workshop chapters. Being able to work closely with Professor Chatterjee has been an incredible experience, as she not only made the thesis writing process more enjoyable, but also challenged me to push my analysis further. I would also like to thank Professor Jih-Fei Cheng, who has been my advisor since my first year. He has provided me with guidance not only throughout my thesis writing process, but also my time at Scripps. Professor Cheng helped me talk through ideas and sections I was struggling with, and provided me with amazing recommendations for work to turn to in order to support my thesis. -

Coming out of Concrete Closets

COMING OUT OF CONCRETE CLOSETS A REPORT ON BLACK & PINK’S NATIONAL LGBTQ PRISONER SURVEY To increase the power of prisoners we need greater access to the Jason Lydon political process. We need real! access to real people in real power with who will actively hear us and help us, not just give us lip service, come Kamaria Carrington sit and talk with me, help me take my dreams and present them to Hana Low the people who can turn them into a reality, I am not persona non Reed Miller grata, hear me, don't patronize me just to keep me quiet, understand that I'm very capable of helping in this fight. ‐Survey respondent Mahsa Yazdy 1 Black & Pink October 2015 www.blackandpink.org This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution‐NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Version 2, 10.21.2015 Cover image: “Alcatraz” by Mike Shelby / CC BY 2.0 , 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Key Findings ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Recommendations ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Policing and Criminalization of LGBTQ People ....................................................................................................... 6 Courts / Bail Reform / -

Prison Sexuality, Part I " ;Exual Assaults, Sex Offender " Ment, Women's Equality, and Conjugal Visiting

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. -------- 1 ~~~ I .XVIX Number 1 ~ Prison Sexuality, Part I " ;exual Assaults, Sex Offender " ment, Women's Equality, and Conjugal Visiting _. (. 120655- U.S. Department of Justice 120664 National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Poinls of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of thE< National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by ~-i~e~~41------------- to the Nationa. Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the copyright owner. Contents NCJRS Page Preface ................•..............................DEC ....5 .. 1'1.0:£ ........... , i John Ortiz Smykla Editorial ......................................... ACQ.u.f.SIT.IO.NS ...... iv William Babcock .. ~. Issues and Controversies with Respect to the Management of AIDS in Corrections. .. 1 Mark Blumberg [AIDS and Prisoners' Rights Law: Deciphering I 20' 4:, ~S the Administrative Guideposts ............................................... 14 Allen F. Anderson [A Demographic and Epidemiological St?-~y of J 2" 0 b S " New York State Inmate AIDS MortalItIes, 1981-1987 . .. 27 Rosemary L. Gido l [The Prevalence of HIV S ropositivity and HIV-Related / Z () 65 7 Illness in Washington State Prisoners ......................................... 33 David Dugdale and Ken Peterson [K~~:~~~::a~:ff J~~~~~~: tr~~~~!;~~. ~~~~~ .................. !. ~.~. ~.~.~ .... 39 Mark Lanier and Belinda R. McCarthy ~nmates' Conceptions of Prison Sexual Assault ................ !. :? ~ ~ C!. !. ... , 53 Richard S. Jones and Thomas J. Schmid ~ [Year of Sexual Assault in Prison Inmates .................... -

Carcerality, Corporeality, and Subjectivity in the Life Narratives By

NO / BODIES: CARCERALITY, CORPOREALITY, AND SUBJECTIVITY IN THE LIFE NARRATIVES BY FRANCO’S FEMALE PRISONERS by HOLLY JANE PIKE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Hispanic Studies School of Languages, Cultures, Art History, and Music College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham December 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis examines female political imprisonment during the early part of Spain’s Franco regime through the life narratives by Carlota O’Neill, Tomasa Cuevas, Juana Don a, and Soledad Real published during the transition. It proposes the foregrounding notion of the ‘No / Body’ to describe the literary, social, and historical eradication and exemplification of the female prisoner as deviant. Using critical theories of genre, gender and sexuality, sociology and philosophy, and human geography, it discusses the concepts of subject, abject, spatiality, habitus, and the mirror to analyse the intersecting, influential factors in the (re)production of dominant discourses within Francoist and post-Francoist society that are interrogated throughout the corpus. -

Gothic Strategies in African American and Latina/O Prison Literature, 1945-2000

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 “The Monster They've Engendered in Me”: Gothic Strategies in African American and Latina/o Prison Literature, 1945-2000 Jason Baumann Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1910 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “THE MONSTER THEY'VE ENGENDERED IN ME”: GOTHIC STRATEGIES IN AFRICAN AMERICAN AND LATINA/O PRISON LITERATURE, 1945-2000 by JASON BAUMANN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 JASON BAUMANN All Rights Reserved ii “THE MONSTER THEY'VE ENGENDERED IN ME”: GOTHIC STRATEGIES IN AFRICAN AMERICAN AND LATINA/O PRISON LITERATURE, 1945-2000 by Jason Baumann This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________ ______________________________________ Date Robert Reid-Pharr Chair of Examining Committee ____________________ ______________________________________ Date Mario DiGangi Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Robert Reid-Pharr Ruth -

Sexual Assault in Jail and Juvenile Facilities: Promising Practices for Prevention and Response, Final Report

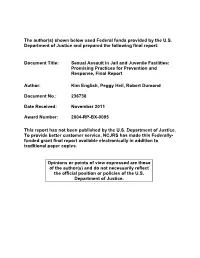

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Sexual Assault in Jail and Juvenile Facilities: Promising Practices for Prevention and Response, Final Report Author: Kim English, Peggy Heil, Robert Dumond Document No.: 236738 Date Received: November 2011 Award Number: 2004-RP-BX-0095 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. SEXUAL ASSAULT IN JAIL AND JUVENILE FACILITIES: PROMISING PRACTICES FOR PREVENTION AND RESPONSE FINAL REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF JUSTICE JUNE 2010 PREPARED BY Kim English Peggy Heil Robert Dumond Colorado Division of Criminal Justice Office of Research and Statistics 700 Kipling Street, Suite 1000 Denver, CO 80215 303.239.4442 http://dcj.state.co.us/ors SEXUAL ASSAULT IN JAIL AND JUVENILE FACILITIES: PROMISING PRACTICES FOR PREVENTION AND RESPONSE FINAL REPORT FOR GRANT NUMBER D04RPBX0095 SUBMITTED TO THE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF JUSTICE JUNE 2010 PREPARED BY Kim English Peggy Heil Robert Dumond Colorado Division of Criminal Justice Office of Research and Statistics 700 Kipling Street, Suite 1000 Denver, CO 80215 303.239.4442 http://dcj.state.co.us/ors This project was funded by Grant Number D04RPBX0095. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position or positions of the U.S. -

Imprisonment and (Un)Relatedness in Northeast Brazil

Imprisonment and (Un)Relatedness in Northeast Brazil by Hollis Moore A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright by Hollis Moore 2017 ii Abstract This dissertation – based on 18 months of ethnographic fieldwork conducted in and around a men’s and a women’s prison – explores imprisonment and (un)relatedness in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. From the vantage point of a prison compound and the heavily penalized neighbourhoods surrounding it, I describe and analyze inextricable connectivities which bind this compound to its social milieu, prison cells to houses, and prisoners to non-prisoners. I focus in particular on the gendered experiences and life projects of male and female “subjects of incarceration” – social actors whose entanglements with the prison are relatively intense, namely: (ex-)prisoners, visitors, and non-visitors (people with an imprisoned relation who do not visit the prison). In short, what is at stake in this dissertation is the question of how social reproduction occurs in a context in which imprisonment has come to be a regular, predictable part of life for poor and racialized groups. To grasp material and symbolic continuities, ruptures, and interconnections constitutive of prison-society relations I have developed the concept of “carceral forms.” This concept offers an approach to delineating objects of inquiry and a set of questions that will enrich multidisciplinary conversations about imprisonment as well as punishment and society. Anthropological insights regarding (un)relatedness have informed my theoretical-methodological approach to practices of imprisonment. This means that I approach penality and penal effects through the ethnographic investigation of gendered social relations forged, maintained, strained, and severed within and across prison boundaries. -

Copyright 2012 Ryan Michael Jones

Copyright 2012 Ryan Michael Jones “ESTAMOS EN TODAS PARTES”: MALE HOMOSEXUALITY, NATION, AND MODERNITY IN TWENTIETH CENTURY MEXICO BY RYAN MICHAEL JONES DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History with minors in Latin American and Caribbean Studies and Gender and Women’s Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Nils Jacobsen, Chair Professor Antoinette Burton Professor Mark Micale Associate Professor Martin Manalansan Associate Professor Jocelyn Olcott, Duke University ABSTRACT In broad strokes my research investigates the intersections between the nation, citizenship, masculinity, and culture as engaged through the lenses of gender, sexuality, and transnational flows of ideas and people. My project is a genealogy of what Mexican citizenship has and has not included as told through discourses on homosexuality and the experiences of homosexuals, a group that for the majority of the 20th century were largely excluded from full citizenship. This did not mean homosexuals were unimportant; on the contrary, they were the foils against which the ideal Mexican could be defined and participants in both democracy and citizenship through their negation. The experiences and challenges faced by homosexuals illuminate the great, if gradual shift, from exclusive definitions of citizenship towards more universal forms of citizenship, however flawed, found in Mexico’s current multiculturalism. In fact, homosexuals’ trajectory from a maligned anti-Mexican group to representatives of pluralist democracy by the late 1970s sheds important light on how Mexico shifted from oligarchy through paternalist state-interventionism towards more participatory politics and towards an understanding of citizenship that incorporated pride parades as Mexican and homosexuals as worthy of state-sanctioned marriage by 2009, even as the structural causes of homophobia remained. -

Masculinity As Prison: Sexual Identity, Race, and Incarceration Russell K

Berkeley Law Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2011 Masculinity as Prison: Sexual Identity, Race, and Incarceration Russell K. Robinson Berkeley Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/facpubs Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Russell K. Robinson, Masculinity as Prison: Sexual Identity, Race, and Incarceration, 99 Cal. L. Rev. 1309 (2011) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Masculinity as Prison: Sexual Identity, Race, and Incarceration Russell K. Robinson* The Los Angeles County Men's Jail segregatesgay and transgender inmates and says that it does so to protect them from sexual assault. But not all gay and transgenderinmates qualify for admission to the K6G unit. Transgender inmates must appear transgender to staff that inspect them. Gay men must identify as gay in a public space and then satisfactorily answer a series of cultural questions designed to determine whether they really are gay. This policy creates harms for those who are excluded, including vulnerable heterosexual and bisexual men, men who have sex with men but do not embrace gay identity, and gay-identified men who do not mimic white, affluent gay culture. Further,the policy harms those who are included in that it stereotypes them as inherent victims, exposes them to a heightened risk of HIV transmission, and disrupts relationships that cut across gender identity and sexual orientation. -

Queering the Carceral: Intersecting Queer/Trans Studies and Critical Prison Studies

Review Essay QUEERING THE CARCERAL Intersecting Queer/Trans Studies and Critical Prison Studies Elias Walker Vitulli Criminal Intimacy: Prison and the Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality Regina Kunzel Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008. xi + 371 pp. Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex Eric A. Stanley and Nat Smith, eds. Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2011. x + 365 pp. Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of Law Dean Spade Brooklyn, NY: South End Press, 2011. 246 pp. In “Queering Antiprison Work: African American Lesbians in the Juvenile Jus- tice System,” Beth Richie calls for a “queer antiprison politic” that takes into account race, sexuality, and gender. She argues that this is necessary in order to attend to the “heteronormative imperatives” of the US prison system, imperatives that are intersectionally structured by gender, sexuality, and race.1 Published in 1995, this article has long been one of the rare queer scholarly engagements with the prison. Despite the fact that queer and especially trans and gender- nonconforming people are disproportionately incarcerated and otherwise affected by the US prison system, queer studies has rarely examined the prison, and criti- cal prison studies has rarely engaged with queerness. However, in the past few GLQ 19:1 DOI 10.1215/10642684- 1729563 © 2012 by Duke University Press 112 GLQ: A JOURNAL OF LESBIAN AND GAY STUDIES years, a new cohort of scholars has taken up Richie’s call and begun to explore the multiple and complex ways that queerness pervades the US prison system and the effects of criminalization and incarceration on queer, gender- and sexual- nonconforming, and LGBT people.