A Case Study of William Inge's Picnic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horton Foote

38th Season • 373rd Production MAINSTAGE / MARCH 29 THROUGH MAY 5, 2002 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing Artistic Director Artistic Director presents the World Premiere of by HORTON FOOTE Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Composer MICHAEL DEVINE MAGGIE MORGAN TOM RUZIKA DENNIS MCCARTHY Dramaturgs Production Manager Stage Manager JENNIFER KIGER/LINDA S. BAITY TOM ABERGER *RANDALL K. LUM Directed by MARTIN BENSON Honorary Producers JEAN AND TIM WEISS, AT&T: ONSTAGE ADMINISTERED BY THEATRE COMMUNICATIONS GROUP PERFORMING ARTS NETWORK / SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P - 1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Constance ................................................................................................... *Annie LaRussa Laverne .................................................................................................... *Jennifer Parsons Mae ............................................................................................................ *Barbara Roberts Frankie ...................................................................................................... *Juliana Donald Fred ............................................................................................................... *Joel Anderson Georgia Dale ............................................................................................ *Linda Gehringer S.P. ............................................................................................................... *Hal Landon Jr. Mrs. Willis ....................................................................................................... -

Bernhardt Hamlet Cast FINAL

IMAGES AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD HERE CAST ANNOUNCED FOR GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE WEST COAST PREMIERE OF “BERNHARDT/HAMLET” FEATURING GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINEE DIANE VENORA AS SARAH BERNHARDT WRITTEN BY THERESA REBECK AND DIRECTED BY SARNA LAPINE ALSO FEATURING NICK BORAINE, ALAN COX, ISAIAH JOHNSON, SHYLA LEFNER, RAYMOND McANALLY, LEVENIX RIDDLE, PAUL DAVID STORY, LUCAS VERBRUGGHE AND GRACE YOO PREVIEWS BEGIN APRIL 7 - OPENING NIGHT IS APRIL 16 LOS ANGELES (February 24, 2020) – Geffen Playhouse today announced the full cast for its West Coast premiere of Bernhardt/Hamlet, written by Theresa Rebeck (Dead Accounts, Seminar) and directed by Sarna Lapine (Sunday in the Park with George). The production features Diane Venora (Bird, Romeo + Juliet) as Sarah Bernhardt. In addition to Venora, the cast features Nick BoraIne (Homeland, Paradise Stop) as Louis, Alan Cox (The Dictator, Young Sherlock Holmes) as Constant Coquelin, Isaiah Johnson (Hamilton, David Makes Man) as Edmond Rostand, Shyla Lefner (Between Two Knees, The Way the Mountain Moved) as Rosamond, Raymond McAnally (Size Matters, Marvelous and the Black Hole) as Raoul, Rosencrantz, and others, Levenix Riddle (The Chi, Carlyle) as Francois, Guildenstern, and others, Paul David Story (The Caine Mutiny Court Martial, Equus) as Maurice, Lucas Verbrugghe (Icebergs, Lazy Eye) as Alphonse Mucha and Grace Yoo (Into The Woods, Root Beer Bandits) as Lysette. It’s 1899, and the legendary Sarah Bernhardt shocks the world by taking on the lead role in Hamlet. While her performance is destined to become one for the ages, Sarah first has to conVince a sea of naysayers that her right to play the part should be based on ability, not gender—a feat as difficult as mastering Shakespeare’s most Verbose tragic hero. -

Board of Directors. I Want to Make Sure That There’S a Diversity Ourselves — We Live with Them for Long Periods of of Voices Being Published by DPS

ISSUE 16 DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE SPRING 2015 ROUND TABLE with JOHN PATRICK SHANLEY, Dramatists Play Service POLLY PEN, and LYNN NOTTAGE is very fortunate not just to publish and license the best BY PETER HAGAN, PRESIDENT American playwrights, but also to have four of them sit on our the publishing conversation. As a woman of always going to be slightly different from that of the color, I also see my role as one of advocacy; agents. Our plays are creative extensions of Board of Directors. I want to make sure that there’s a diversity ourselves — we live with them for long periods of of voices being published by DPS. time; we keep them close and protected until we release them into the world. The founding charter of the Play Service, back in As time has gone by, have you seen your Then we entrust our plays 1936, called for the Board to be split evenly position as a playwright member change? to others for safekeeping: between playwrights (all members of the initially agents, and eventually Dramatists Guild) and agents. Back then, the star John Patrick Shanley: When I first served on publishing companies like playwrights included Howard Lindsay, George the Board, I was skeptical and challenging DPS. For better or worse, Abbott, and Sidney Howard. Today our stars are and, frankly, young. But over time I morphed agents can approach the Donald Margulies, Polly Pen, Lynn Nottage, and from opponent to colleague. business of publishing with John Patrick Shanley, who have been members a certain level of objectivity of the board ranging from five years (Nottage) to PP: Ways of thinking about how theatrical and distance; however, it’s over 20 (Shanley). -

Theatrical CV

Represented by Miles Polaski SOUND DESIGNER & COMPOSER Michael Griffo [email protected] 773.905.4529 [email protected] www.milespolaski.com 212-556-6714 SOUND DESIGN — PLAYS (selected credits) PRODUCTION PLAYWRIGHT PRODUCING COMPANY DIRECTOR WHERE STORMS ARE BORN Harrison David Rivers Williamstown T h eatre Festival Saheem Ali TWO CLASS ACTS A.R. Gurney The Flea Theatre Stafford Arima FULFILLMENT Thomas Bradshaw The Flea Theatre Ethan McSweeny BOOK OF JOSEPH Karen Hartman Chicago Shakespeare Theatre Barbara Gaines BYHALIA MISSISSIPPI Evan Linder Contemporary American Thtr. Fest. Marc Masterson WASHER DRYER Nandita Shenoy Ma-Yi Theatre Benjamin Kamine SAGITTARIUS PONDEROSA MJ Kaufman Nat. Asian American Theatre Co. Ken Rus Schmoll A CHRISTMAS CAROL add. James Palmer Trinity Repertory James D. Palmer THE HAIRY APE Eugene O’Neill Goodman / The Hypocrites Sean Graney MEN ON BOATS Jaclyn Backhaus American Theatre Company William Davis PICNIC and ...LITTLE SHEBA William Inge Transport Group Jack Cummings III WANT Zayd Dohrn Steppenwolf Theatre Kimberly Senior MAN IN LOVE Christina Anderson Steppenwolf Theatre Robert O’Hara THE KID THING Sarah Gubbins Chicago Dramatists -

Selected Correspondence from the Horton Foote

SELECTED CORRESPONDENCE FROM THE HORTON FOOTE COLLECTION, 1912-1991 by SUSAN CHRISTENSEN Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Horton Foote for his generosity in granting me permission to include transcriptions of his family members’ correspondence in my dissertation. I would also like to thank his daughter Hallie for her kind assistance. I have been fortunate to have the opportunity to work with Dr. Laurin Porter, my supervising professor, an extraordinary teacher, a remarkable scholar, and a generous and thoughtful person. During my graduate studies, her wisdom has inspired me and her encouragement has sustained me. I would like to extend my heartfelt appreciation to the members of my graduate committee, Dr. Desirée Henderson and Dr. Neill Matheson, and also to Dr. Wendy Faris and Dr. Thomas Porter, for their kindness and their work on my behalf. I am grateful to Dr. Russell Martin III, the director of the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University, and his staff, who assisted me during the many months I spent conducting archival research. Finally, and most importantly, I would like to thank my husband Robert for his unwavering support and love. July 16, 2008 ii ABSTRACT SELECTED CORRESPONDENCE FROM THE HORTON FOOTE COLLECTION, 1912-1991 Susan Christensen, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2008 Supervising Professor: Laurin Porter This dissertation includes a discussion of archival research and editorial procedures employed in the study, introductory essays on the private correspondence of the family of Horton Foote, and transcriptions of one hundred letters selected from the personal correspondence in the Horton Foote Collection reposited in the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, with extensive annotations and ancillary materials. -

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected]

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected] CASTING DIRECTOR (selected) Holler If Ya Hear Me (Todd Kreidler) Palace Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon (upcoming) Casa Valentina (Harvey Fierstein) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello (upcoming) Commons of Pensacola (Amanda Peet) Manhattan Theater Club dir. Lynne Meadow The Snow Geese (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan All New People (Zach Braff) Second Stage Theatre dir. Peter DuBois Water By The Spoonful (Quiara Hudes) Second Stage Theatre dir. Davis McCallum My Name Is Rachel Corrie Minetta Lane/Off-Broadway dir. Alan Rickman Complicit (Joe Sutton) Old Vic/London dir. Kevin Spacey Orphans (Lyle Kessler) Schoenfeld Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan Lonely I’m Not (Paul Weitz) Second Stage Theatre dir. Trip Cullman Tales of the City: the musical American Conservatory Theatre dir: Jason Moore Romantic Poetry (John P. Shanley) MTC/Off-Broadway dir: John P. Shanley Trip to Bountiful (Horton Foote) Sondheim Theatre/ Broadway dir. Michael Wilson Dead Accounts (Theresa Rebeck) Music Box Theatre/ Broadway dir. Jack O’Brien Fences (August Wilson) Cort Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon Sweet Bird of Youth (T. Williams) Goodman Theatre/ Chicago dir. David Cromer The Other Place (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello Seminar (Theresa Rebeck) Golden Theatre/ Broadway dir. Sam Gold Grace (Craig Wright) Court Theatre/ Broadway dir. Dexter Bullard Bengal Tiger … (Rajiv Josef) Richard Rodgers/ Broadway dir. Moises Kaufman Stick Fly (Lydia Diamond) Cort Theatre/ Broadway dir. Kenny Leon The Columnist (David Auburn) Freidman Theatre/Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan The Royal Family (Ferber) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. -

The Pin-Up Boy of the Symphony: St. Louis and the Rise of Leonard

The Pin-Up Boy of the Symphony St. Louis and the Rise of Leonard Bernstein BY KENNETH H. WINN 34 | The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2018/2019 In May 1944 25-year-old publicized story from a New Leonard Bernstein, riding a York high school newspaper, had tidal wave of national publicity, bobbysoxers sighing over him as was invited to serve as a guest the “pin-up boy of the symphony.” conductor of the St. Louis They, however, advised him to get The Pin-Up Boy 3 Symphony Orchestra for its a crew cut. 1944–1945 season. The orchestra For some of Bernstein’s of the Symphony and Bernstein later revealed that elders, it was too much, too they had also struck a deal with fast. Many music critics were St. Louis and the RCA’s Victor Records to make his skeptical, put off by the torrent first classical record, a symphony of praise. “Glamourpuss,” they Rise of Leonard Bernstein of his own composition, entitled called him, the “Wunderkind Jeremiah. Little more than a year of the Western World.”4 They BY KENNETH H. WINN earlier, the New York Philharmonic suspected Bernstein’s performance music director Artur Rodziński Jeremiah was the first of Leonard Bernstein’s was simply a flash-in-the-pan. had hired Bernstein on his 24th symphonies recorded by the St. Louis Symphony The young conductor was riding birthday as an assistant conductor, Orchestra in the spring of 1944. (Image: Washing- a wave of luck rather than a wave a position of honor, but one known ton University Libraries, Gaylord Music Library) of talent. -

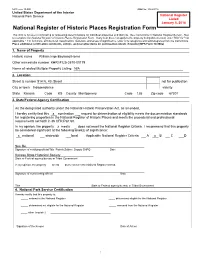

National Register Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register Listed January 5, 2018 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property Historic name William Inge Boyhood Home Other names/site number KHRI #125-2670-00179 Name of related Multiple Property Listing N/A 2. Location Street & number 514 N. 4th Street not for publication City or town Independence vicinity State Kansas Code KS County Montgomery Code 125 Zip code 67301 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: x national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A x B C ___D See file. -

Christopher Hampton, John Patrick Shanley, Patricia Marx and Theresa Rebeck December 2009 | Volume #31

IN THIS ISSUE: Christopher Hampton, John Patrick Shanley, Patricia Marx and Theresa Rebeck December 2009 | Volume #31 EDITOR A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR Arlene Hellerman Donald Westlake often said, “When I write a COPY EDITOR novel, I’m God, and when I write a screenplay, Shelley Wolson I’m cup-bearer to the gods.” The same could be DESIGNER said of the relationship between screenwriting Tom Beckham and playwriting. SUPERVISING CONSULTANT The conversations in this issue cover both Marsha Seeman of these genres. John Patrick Shanley and CONSULTANT Christopher Hampton talk about playwriting, Nicole Revere screenwriting and directing. Theresa Rebeck and Patricia Marx talk about writing plays and films, ADVISOR but also about the process of writing prose. Marc Siegel On The Back Page we’re publishing Gina Gionfriddo’s one-act play America’s Got Tragedy. Michael Winship | president Bob Schneider | vice president Gail Lee | secretary-treasurer — Arlene Hellerman Lowell Peterson | executive director All correspondence should be addressed to The Writers Guild of America, East 555 West 57th Street New York, New York 10019 Telephone: 212-767-7800 Fax: 212-582-1909 www.wgaeast.org Copyright © 2009 by the Writers Guild of America, East, Inc. Christopher Hampton AND John Patrick Shanley New York CitY – April 27, 2009 SHANLEY: I have questions for you. HAMPTON: Between 5 and 10. HAMPTON: Oh, do you? ON WRITING: Do you think that gave you a different perspective when you got back to England? Did you SHANLEY: Questions that are sort of simple but inter- see it as an outsider? esting to me. One is, when you started writing, was there either a play that you wanted to do something HAMPTON: Yes, very much so. -

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for Your Wife

Sunset Playhouse Production History 2020-21 Season Run for your Wife by Ray Cooney presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French 9 to 5, The Musical by Dolly Parton presented by special arrangement with MTI Elf by Thomas Meehan & Bob Martin presented by special arrangement with MTI 4 Weddings and an Elvis by Nancy Frick presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French The Cemetery Club by Ivan Menchell presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Young Frankenstein by Mel Brooks presented by special arrangement with MTI An Inspector Calls by JB Priestley presented by special arrangement with Concord Theatricals for Samuel French Newsies by Harvey Fierstein presented by special arrangement with MTI _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2019-2020 Season A Comedy of Tenors – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Mamma Mia – presented by special arrangement with MTI The Game’s Afoot – by Ken Ludwig presented by special arrangement with Samuel French The Marvelous Wonderettes – by Roger Bean presented by special arrangement with StageRights, Inc. Noises Off – by Michael Frayn presented by special arrangement with Samuel French Cabaret – by Joe Masteroff presented by special arrangement with Tams-Witmark Barefoot in the Park – by Neil Simon presented by special arrangement with Samuel French (cancelled due to COVID 19) West Side Story – by Jerome Robbins presented by special arrangement with MTI (cancelled due to COVID 19) 2018-2019 Season The Man Who Came To Dinner – by Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Mary Poppins - Original Music and Lyrics by Richard M. -

Motherandchild Presskit FINAL

Sony Pictures Classics In Association With Everest Entertainment Presents A Mockingbird Pictures Production MOTHER AND CHILD A Film by Rodrigo Garcia Naomi Watts Annette Bening Kerry Washington Jimmy Smits and Samuel L. Jackson Producers: Lisa Maria Falcone, Julie Lynn Executive Producer: Alejandro González Iñárritu Running Time: 126 Minutes Camera: Genesis Exhibited on 35mm print East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Falco Ink. Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Janice Roland Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Rebecca Fisher Lindsay Macik Annie McDonough Judy Chang 550 Madison Ave 850 7th Avenue, Suite 1005 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 212-445-7100 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 212-445-0623 fax 323-634-7030 fax MOTHER AND CHILD Synopsis Three women's lives share a common core: they have all been profoundly affected by adoption. KAREN (Annette Bening) had a baby at 14, gave her up at birth, and has been haunted ever since by the daughter she never knew. ELIZABETH (Naomi Watts) grew up as an adopted child; she's a bright and ambitious lawyer, but a flinty loner in her personal life. LUCY (Kerry Washington) is just embarking with her husband on the adoption odyssey, looking for a baby to become their own. Karen lives with her elderly mother NORA (Eileen Ryan), works as a physical therapist in a rehabilitation clinic, and relies on SOFIA (Elpidia Carrillo) to look after Nora and their home while she is working. While Karen and Nora barely speak, Karen keeps up a silent monologue addressed to her absent daughter, writing journal entries and letters never to be sent. -

What the Inge Center Is Planning for Our Students This Year This Fall We Will Produce a Wild, Madcap Political Comedy the Empero

What the Inge Center is planning for our students this year This fall we will produce a wild, madcap political comedy The Emperor’s New Clothes by Richard Hellesen in the style of the Marx Brothers; a musical adaptation of Dylan Thomas’ literary masterpiece, A Child’s Christmas in Wales adapted and directed by guest playwright Brian Burgess Clark in co-production with the ICC music program; the contemporary drama Aliens by Annie Baker, one of America’s leading young playwrights, The Anna Plays, a student-chosen and generated production of selected short plays under the mentorship of Artistic Director Peter Ellenstein; the 33rd Annual William Inge Theatre Festival honoring one of America’s great playwrights and featuring over 50 events in four days, and a musical theatre production of Rogers and Hammerstein’s classic Carousel, in collaboration with the ICC music program. In addition, we’ll produce two iterations of the wildly creative 24-Hour Plays, at least four new play development workshops by our resident playwrights, multiple series of guest artist workshops for regional high school students, and two sets of readings of new plays by our own playwriting students. Our guest artists for the fall so far include: . Brian Burgess Clark: Award-winning playwright and Artistic Director of Boston Children’s Theatre o Playwright-in-Residence and Director of A Child’s Christmas in Wales . Stephen Gregg: One of America’s most produced playwrights for High School Theatre o Playwright-in-Residence . Stefan Haves: Clown coach and director for Cirque du Soleil o Clown and Comedy coach for The Emperor’s new Clothes .