National Register Nomination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S11474

S11474 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð SENATE September 27, 1996 as nutrition problems, disease, and har- The NMFS laboratory in Pascagoula forming more partnerships with indus- vesting technology. There were many committed itself because of its can do try. costly false starts in a search for solu- attitude. And clearly USDA and Mis- Mr. President, Stoneville should be tions. Success was a hit or miss event. sissippi State University were recep- the standard in the future, not the ex- Gradually, solutions to feeding and tive. NMFS brought a range of poten- ception. health problems have been developed. tial solutions to the harvesting tech- Again, I applaud the efforts of the Today, part of the catfish industry's nology problems of the warmwater National Marine Fisheries Service and attention is focused on obtaining new aquaculture industry because they had I want to publicly thank them. They technology. This involves the National worked on this issue for years in the have significantly helped America's Marine Fisheries Service. The goal is marine fishing industry. I want to sin- farm-raised catfish industry. I strongly to take advantage of existing tech- gle out two individuals. Specifically, encourage the continuation of the suc- nology. John Watson and Charles ``Wendy'' cessful relationship between Stoneville Now, to many Americans fish are Taylor of NMFS's Pascagoula labora- and Pascagoula. fish. To some, fish are classified as ei- tory. These two directly assisted in the f ther fresh water or salt water. Here is development and retrofitting of har- THE ACADEMY OF TELEVISION where the Federal Government often vesting equipment. -

Horton Foote

38th Season • 373rd Production MAINSTAGE / MARCH 29 THROUGH MAY 5, 2002 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing Artistic Director Artistic Director presents the World Premiere of by HORTON FOOTE Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Composer MICHAEL DEVINE MAGGIE MORGAN TOM RUZIKA DENNIS MCCARTHY Dramaturgs Production Manager Stage Manager JENNIFER KIGER/LINDA S. BAITY TOM ABERGER *RANDALL K. LUM Directed by MARTIN BENSON Honorary Producers JEAN AND TIM WEISS, AT&T: ONSTAGE ADMINISTERED BY THEATRE COMMUNICATIONS GROUP PERFORMING ARTS NETWORK / SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P - 1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Constance ................................................................................................... *Annie LaRussa Laverne .................................................................................................... *Jennifer Parsons Mae ............................................................................................................ *Barbara Roberts Frankie ...................................................................................................... *Juliana Donald Fred ............................................................................................................... *Joel Anderson Georgia Dale ............................................................................................ *Linda Gehringer S.P. ............................................................................................................... *Hal Landon Jr. Mrs. Willis ....................................................................................................... -

IGOR GOLDIN Director, Sdc Contact: Ronald Gwiazda 718-809-3068 Abrams Artists Agency [email protected] 646-461-9325 [email protected]

IGOR GOLDIN director, sdc Contact: Ronald Gwiazda 718-809-3068 Abrams Artists Agency [email protected] 646-461-9325 [email protected] OFF-BROADWAY YANK! YORK THEATRE COMPANY book & lyrics by David Zellnik, music by Joseph Zellnik md: John Baxindine choreo: Jeffry Denman *Drama Desk Award nomination - OUTSTANDING DIRECTOR OF A MUSICAL *SDC Joe A. Callaway finalist for DISTINGUISHED DIRECTION WITH GLEE PROSPECT THEATRE COMPANY book, music & lyrics by John Gregor md: Daniel Feyer choreo: Antoinette DiPietropolo *New York Times Critics Pick *BEST STAGING OF A BIG NUMBER IN A PUNY SPACE, New York Times year end list A RITUAL OF FAITH EMERGING ARTISTS by Brad Levinson OTHER NYC & REGIONAL WEST SIDE STORY ENGEMAN THEATRE at NORTHPORT book by Arthur Laurents, music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim md: James Olmstead choreo: Jeffry Denman SWEENEY TODD MERRY-GO-ROUND, FINGER LAKES, NY music & lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, book by Hugh Wheeler md: Jeff Theiss BABY INFINITY THEATRE, ANNAPOLIS, MD book by Sybille Pearson, music by David Shire, lyrics by Richard Maltby, Jr. md: Jeffrey Lodin THE PRODUCERS ENGEMAN THEATER at NORTHPORT book by Mel Brooks & Thomas Meehan, music & lyrics by Mel Brooks md: James Olmstead choreo: Antoinette DiPietropolo JANE AUSTEN’S PRIDE AND PREJUDICE a musical McCOY/RIGBY ENTERTAINMENT/ book, music & lyrics by Lindsay Warren Baker and Amanda Jacobs LA MIRADA, CA md: Timothy Splain choreo: Jeffry Denman TICK, TICK…BOOM! AMERICAN THEATRE GROUP, NJ book, music & lyrics by Jonathan Larson, David -

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009

JOHN J. ROSS–WILLIAM C. BLAKLEY LAW LIBRARY NEW ACQUISITIONS LIST: February 2009 Annotations and citations (Law) -- Arizona. SHEPARD'S ARIZONA CITATIONS : EVERY STATE & FEDERAL CITATION. 5th ed. Colorado Springs, Colo. : LexisNexis, 2008. CORE. LOCATION = LAW CORE. KFA2459 .S53 2008 Online. LOCATION = LAW ONLINE ACCESS. Antitrust law -- European Union countries -- Congresses. EUROPEAN COMPETITION LAW ANNUAL 2007 : A REFORMED APPROACH TO ARTICLE 82 EC / EDITED BY CLAUS-DIETER EHLERMANN AND MEL MARQUIS. Oxford : Hart, 2008. KJE6456 .E88 2007. LOCATION = LAW FOREIGN & INTERNAT. Consolidation and merger of corporations -- Law and legislation -- United States. ACQUISITIONS UNDER THE HART-SCOTT-RODINO ANTITRUST IMPROVEMENTS ACT / STEPHEN M. AXINN ... [ET AL.]. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y. : Law Journal Press, c2008- KF1655 .A74 2008. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Consumer credit -- Law and legislation -- United States -- Popular works. THE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION GUIDE TO CREDIT & BANKRUPTCY. 1st ed. New York : Random House Reference, c2006. KF1524.6 .A46 2006. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. Construction industry -- Law and legislation -- Arizona. ARIZONA CONSTRUCTION LAW ANNOTATED : ARIZONA CONSTITUTION, STATUTES, AND REGULATIONS WITH ANNOTATIONS AND COMMENTARY. [Eagan, Minn.] : Thomson/West, c2008- KFA2469 .A75. LOCATION = LAW RESERVE. 1 Court administration -- United States. THE USE OF COURTROOMS IN U.S. DISTRICT COURTS : A REPORT TO THE JUDICIAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE ON COURT ADMINISTRATION & CASE MANAGEMENT. Washington, DC : Federal Judicial Center, [2008] JU 13.2:C 83/9. LOCATION = LAW GOV DOCS STACKS. Discrimination in employment -- Law and legislation -- United States. EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION : LAW AND PRACTICE / CHARLES A. SULLIVAN, LAUREN M. WALTER. 4th ed. Austin : Wolters Kluwer Law & Business ; Frederick, MD : Aspen Pub., c2009. KF3464 .S84 2009. LOCATION = LAW TREATISES. -

The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21St- Century Actress

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2009 Then & Now: The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21st- Century Actress Marcie Danae Bealer Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bealer, Marcie Danae, "Then & Now: The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21st- Century Actress" (2009). Honors Theses. 24. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/24 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Then & Now: The Relevance of Tennessee Williams for the 21st- Century Actress Marcie Danae Bealer Honors Thesis Ouachita Baptist University Spring 2009 Bealer 2 Finding a place to begin, discussing the role Tennessee Williams has played in the American Theatre is a daunting task. As a playwright Williams has "sustained dramatic power," which allow him to continue to be a large part of American Theatre, from small theatre groups to actor's workshops across the country. Williams holds a central location in the history of American Theatre (Roudane 1). Williams's impact is evidenced in that "there is no actress on earth who will not testify that Williams created the best women characters in the modem theatre" (Benedict, par 1). According to Gore Vidal, "it is widely believed that since Tennessee Williams liked to have sex with men (true), he hated women (untrue); as a result his women characters are thought to be malicious creatures, designed to subvert and destroy godly straightness" (Benedict, par. -

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

View the Playbill

GEORGE STREET PLAYHOUSE The Second Mrs.Wilson Board of Trustees Chairman: James N. Heston* President: Dr. Penelope Lattimer* First Vice President: Lucy Hughes* Second Vice President: Janice Stolar* Treasurer: David Fasanella* Secretary: Sharon Karmazin* Ronald Bleich David Saint* David Capodanno Jocelyn Schwartzman Kenneth M. Fisher Lora Tremayne William R. Hagaman, Jr. Stephen M. Vajtay Norman Politziner Alan W. Voorhees Kelly Ryman* *Denotes Members of the Executive Committee Trustees Emeritus Robert L. Bramson Cody P. Eckert Clarence E. Lockett Al D’Augusta Peter Goldberg Anthony L. Marchetta George Wolansky, Jr. Honorary Board of Trustees Thomas H. Kean Eric Krebs Honorary Memoriam Maurice Aaron∆ Arthur Laurents∆ Dr. Edward Bloustein∆ Richard Sellars∆ Dora Center∆∆ Barbara Voorhees∆∆ Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.∆ Edward K. Zuckerman∆ Milton Goldman∆ Adelaide M. Zagoren John Hila ∆∆ – Denotes Trustee Emeritus ∆ – Denotes Honorary Trustee From the Artistic Director It is a pleasure to welcome back playwright Joe DiPietro for his fifth premiere here at George Street Playhouse! I am truly astonished at the breadth of his talent! From the wild farce of The Toxic Photo by: Frank Wojciechowski Avenger to the drama of Creating Claire and the comic/drama of Clever Little Lies, David Saint Artistic Director now running at the West Side Theatre in Manhattan, he explores all genres. And now the sensational historical romance of The Second Mrs.Wilson. The extremely gifted Artistic Director of Long Wharf Theatre, Gordon Edelstein, brings a remarkable company of Tony Award-winning actors, the top rank of actors working in American theatre today, to breathe astonishing life into these characters from a little known chapter of American history. -

Southern Comfort

FROM THE NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MUSICAL THEAtre’s PresideNT Welcome to our 24th Annual Festival of New Musicals! The Festival is one of the highlights of the NAMT year, bringing together 600+ industry professionals for two days of intense focus on new musical theatre works and the remarkably talented writing teams who create them. This year we are particularly excited not only about the quality, but also about the diversity—in theme, style, period, place and people—represented across the eight shows that were selected from over 150 submissions. We’re visiting 17th-century England and early 20th century New York. We’re spending some time in the world of fairy tales—but not in ways you ever have before. We’re visiting Indiana and Georgia and the world of reality TV. Regardless of setting or stage of development, every one of these shows brings something new—something thought-provoking, funny, poignant or uplifting—to the musical theatre field. This Festival is about helping these shows and writers find their futures. Beyond the Festival, NAMT is active year-round in supporting members in their efforts to develop new works. This year’s Songwriters Showcase features excerpts from just a few of the many shows under development (many with collaboration across multiple members!) to salute the amazing, extraordinarily dedicated, innovative work our members do. A final and heartfelt thank you: our sponsors and donors make this Festival, and all of NAMT’s work, possible. We tremendously appreciate your support! Many thanks, too, to the Festival Committee, NAMT staff and all of you, our audience. -

Bernhardt Hamlet Cast FINAL

IMAGES AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD HERE CAST ANNOUNCED FOR GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE WEST COAST PREMIERE OF “BERNHARDT/HAMLET” FEATURING GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINEE DIANE VENORA AS SARAH BERNHARDT WRITTEN BY THERESA REBECK AND DIRECTED BY SARNA LAPINE ALSO FEATURING NICK BORAINE, ALAN COX, ISAIAH JOHNSON, SHYLA LEFNER, RAYMOND McANALLY, LEVENIX RIDDLE, PAUL DAVID STORY, LUCAS VERBRUGGHE AND GRACE YOO PREVIEWS BEGIN APRIL 7 - OPENING NIGHT IS APRIL 16 LOS ANGELES (February 24, 2020) – Geffen Playhouse today announced the full cast for its West Coast premiere of Bernhardt/Hamlet, written by Theresa Rebeck (Dead Accounts, Seminar) and directed by Sarna Lapine (Sunday in the Park with George). The production features Diane Venora (Bird, Romeo + Juliet) as Sarah Bernhardt. In addition to Venora, the cast features Nick BoraIne (Homeland, Paradise Stop) as Louis, Alan Cox (The Dictator, Young Sherlock Holmes) as Constant Coquelin, Isaiah Johnson (Hamilton, David Makes Man) as Edmond Rostand, Shyla Lefner (Between Two Knees, The Way the Mountain Moved) as Rosamond, Raymond McAnally (Size Matters, Marvelous and the Black Hole) as Raoul, Rosencrantz, and others, Levenix Riddle (The Chi, Carlyle) as Francois, Guildenstern, and others, Paul David Story (The Caine Mutiny Court Martial, Equus) as Maurice, Lucas Verbrugghe (Icebergs, Lazy Eye) as Alphonse Mucha and Grace Yoo (Into The Woods, Root Beer Bandits) as Lysette. It’s 1899, and the legendary Sarah Bernhardt shocks the world by taking on the lead role in Hamlet. While her performance is destined to become one for the ages, Sarah first has to conVince a sea of naysayers that her right to play the part should be based on ability, not gender—a feat as difficult as mastering Shakespeare’s most Verbose tragic hero. -

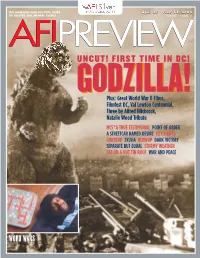

Uncut! First Time In

45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:38 AM Page 1 THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE April 23 - June 13, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 10 AFIPREVIEW UNCUT! FIRST TIME IN DC! GODZILLA!GODZILLA! Plus: Great World War II Films, Filmfest DC, Val Lewton Centennial, Three by Alfred Hitchcock, Natalie Wood Tribute MC5*A TRUE TESTIMONIAL POINT OF ORDER A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE CITY LIGHTS GODSEND SYLVIA BLOWUP DARK VICTORY SEPARATE BUT EQUAL STORMY WEATHER CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF WAR AND PEACE PHOTO NEEDED WORD WARS 45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:39 AM Page 2 Features 2, 3, 4, 7, 13 2 POINT OF ORDER MEMBERS ONLY SPECIAL EVENT! 3 MC5 *A TRUE TESTIMONIAL, GODZILLA GODSEND MEMBERS ONLY 4WORD WARS, CITY LIGHTS ●M ADVANCE SCREENING! 7 KIRIKOU AND THE SORCERESS Wednesday, April 28, 7:30 13 WAR AND PEACE, BLOWUP When an only child, Adam (Cameron Bright), is tragically killed 13 Two by Tennessee Williams—CAT ON A HOT on his eighth birthday, bereaved parents Rebecca Romijn-Stamos TIN ROOF and A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE and Greg Kinnear are befriended by Robert De Niro—one of Romijn-Stamos’s former teachers and a doctor on the forefront of Filmfest DC 4 genetic research. He offers a unique solution: reverse the laws of nature by cloning their son. The desperate couple agrees to the The Greatest Generation 6-7 experiment, and, for a while, all goes well under 6Featured Showcase—America Celebrates the the doctor’s watchful eye. Greatest Generation, including THE BRIDGE ON The “new” Adam grows THE RIVER KWAI, CASABLANCA, and SAVING into a healthy and happy PRIVATE RYAN young boy—until his Film Series 5, 11, 12, 14 eighth birthday, when things start to go horri- 5 Three by Alfred Hitchcock: NORTH BY bly wrong. -

Through FILMS 70 Years of European History Through Films Is a Product in Erasmus+ Project „70 Years of European History 1945-2015”

through FILMS 70 years of European History through films is a product in Erasmus+ project „70 years of European History 1945-2015”. It was prepared by the teachers and students involved in the project – from: Greece, Czech Republic, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey. It’ll be a teaching aid and the source of information about the recent European history. A DANGEROUS METHOD (2011) Director: David Cronenberg Writers: Christopher Hampton, Christopher Hampton Stars: Michael Fassbender, Keira Knightley, Viggo Mortensen Country: UK | GE | Canada | CH Genres: Biography | Drama | Romance | Thriller Trailer In the early twentieth century, Zurich-based Carl Jung is a follower in the new theories of psychoanalysis of Vienna-based Sigmund Freud, who states that all psychological problems are rooted in sex. Jung uses those theories for the first time as part of his treatment of Sabina Spielrein, a young Russian woman bro- ught to his care. She is obviously troubled despite her assertions that she is not crazy. Jung is able to uncover the reasons for Sa- bina’s psychological problems, she who is an aspiring physician herself. In this latter role, Jung employs her to work in his own research, which often includes him and his wife Emma as test subjects. Jung is eventually able to meet Freud himself, they, ba- sed on their enthusiasm, who develop a friendship driven by the- ir lengthy philosophical discussions on psychoanalysis. Actions by Jung based on his discussions with another patient, a fellow psychoanalyst named Otto Gross, lead to fundamental chan- ges in Jung’s relationships with Freud, Sabina and Emma. -

By the Way, Meet Vera Stark by Lynn Nottage

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Dafina McMillan October 8, 2013 [email protected] 212-609-5955 New from TCG Books: By the Way, Meet Vera Stark by Lynn Nottage NEW YORK, NY – Theatre Communications Group (TCG) is pleased to announce the publication of By the Way, Meet Vera Stark by Lynn Nottage, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Ruined. Declared “one of our finest playwrights” by Time Out New York, Lynn Nottage premiered her newest play at Second Stage Theatre in spring 2011. In the 2013-2014 season, the play will receive productions at seven theaters across the country, including the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta and the Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte. “A dazzling comedy about racial identity in Hollywood… That this show is so informed and incisive while being wildly entertaining may be Nottage’s biggest achievement.” — New York Post In By the Way, Meet Vera Stark, Lynn Nottage examines the legacy of African-Americans in Hollywood in a dramatic stylistic departure from her previous work. Fluidly incorporating film and video elements into her writing for the first time, Nottage’s comedy tells the story of Vera Stark, an African-American maid and budding actress who has a tangled relationship with her boss, a white Hollywood star desperately grasping to hold onto her career. When circumstances collide and both women land roles in the same Southern epic, the story behind the cameras leaves Vera with a surprising and controversial legacy scholars will debate for years to come. As a compliment to the play’s experience, the author has developed two websites that will tell the continuing story of Vera Stark: MeetVeraStark.com and FindingVeraStark.com.