Management Information Notes for Bezzants Lease Conservation Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differences in Functional Trait Distribution Between Inselberg and Adjacent Matrix Floras

Hindawi Publishing Corporation International Journal of Ecology Volume 2016, Article ID 6417913, 7 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/6417913 Research Article Differences in Functional Trait Distribution between Inselberg and Adjacent Matrix Floras John T. Hunter School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, Australia Correspondence should be addressed to John T. Hunter; [email protected] Received 30 June 2016; Accepted 26 September 2016 Academic Editor: Bela´ Tothm´ er´ esz´ Copyright © 2016 John T. Hunter. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Inselbergs and the adjacent matrix represent extremes of different environmental conditions and should shed light on the changing allocation of plant resources across strong and abrupt resource gradients. Here I use collated life history trait data from 840 taxa found within typical insular inselberg and adjacent matrix floras from the New England Batholith region of eastern Australia. These species were sorted into guilds of specificity to the inselberg environment. Scored traits include life form, plant height, leaf area, fruit size, seed size, mono- or polycarpy, underground storage organs, regenerative/clonality, and flowering phenology. With reduced water and nutrient resources, typical of inselbergs, allocation of plant resources to vegetative reproduction and storage organs is a disadvantage. Plants restricted to inselbergs were shorter, usually polycarpic shrubs, with smaller leaves, fruits, and seeds. Flowering time was found to be earlier and reduced in length; diaspores often have dormancy and are dispersed locally in comparison to the matrix. -

Ecological Assessment Report

Ecological Assessment Report White Rock Wind Farm Near Glen Innes, NSW Prepared by: Prepared for: RPS Epuron Pty Ltd PO Box 428 Level 11, 75 Miller Street Hamilton NSW 2303 North Sydney NSW 2060 T: +61 4940 4200 F: +61 4961 6794 E: [email protected] W: rpsgroup.com.au Report No: 104226 Version/Date: Final / March 2011 rpsgroup.com.au Document Status Review Format Issue Version Purpose of Document Orig Review Approval Date Review Date Draft 1 Draft for Client Review PH TL 23-11-10 JH 24-11-10 T Lambert 24-11-10 Draft 2 Draft for Client Review PH TL 26-11-10 - T Lambert 26-11-10 Final Final for Issue PH TL 13-12-10 JH 13-12-10 T Lambert 13-12-10 Final Revised Final for Issue PH TL 7-3-11 - T Lambert 7-3-11 Disclaimers This document is and shall remain the property of RPS. The document may only be used for the purposes for which it was commissioned and in accordance with the Terms of Engagement for the commission. Unauthorised copying or use of this document in any form whatsoever is prohibited. rpsgroup.com.au Executive Summary This report undertakes a flora and fauna assessment for a proposal south-west of Glen Innes, NSW. The proposal would comprise 119 wind turbines, with a maximum height of 150 metres, and associated powerlines and access roads. Two Endangered Ecological Communities (EECs) were identified within the study area, namely, Ribbon Gum – Mountain Gum Woodland (EEC – Ribbon Gum – Mountain Gum – Snow Gum Grassy Forest/Woodland of the New England Tableland Region) and Yellow Box Woodland (EEC White Box Yellow Box Blakely's Red Gum Woodland). -

CAEPR WORKING PAPER No. 75/2010

CENTRE FOR ABORIGINAL ECONOMIC POLICY RESEARCH Looking After Country in New South Wales: Two Case Studies of Socioeconomic Benefits for Aboriginal People J. Hunt CAEPR WORKING PAPER No. 75/2010 ANU COLLEGE OF ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES Series Note The Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR) was established at The Australian National University (ANU) in April 1990. Since 1 January 2010, CAEPR has operated as an academic unit within the Research School of Social Sciences in the College of Arts and Social Sciences at ANU. The Centre is funded from a variety of sources including ANU, Australian Research Council, industry and philanthropic partners, the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, and State and Territory governments. CAEPR’s principal objective is to undertake high-quality, independent research that will assist in furthering the social and economic development and empowerment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people throughout Australia. Its aim is to combine academic and teaching excellence on Indigenous economic and social development and public policy with realism, objectivity and relevance. CAEPR is Australia’s foremost social science research centre focusing on Indigenous economic and social policy from a national perspective. The Centre’s publications, which include the CAEPR Working Paper series established in 1999, aim to report on Indigenous circumstance, inform public debate, examine government policy, and influence policy formulation. Working Papers are often work-in-progress -

NPWS Annual Report 2000-2001 (PDF

Annual report 2000-2001 NPWS mission NSW national Parks & Wildlife service 2 Contents Director-General’s foreword 6 3 Conservation management 43 Working with Aboriginal communities 44 Overview 8 Joint management of national parks 44 Mission statement 8 Performance and future directions 45 Role and functions 8 Outside the reserve system 46 Partners and stakeholders 8 Voluntary conservation agreements 46 Legal basis 8 Biodiversity conservation programs 46 Organisational structure 8 Wildlife management 47 Lands managed for conservation 8 Performance and future directions 48 Organisational chart 10 Ecologically sustainable management Key result areas 12 of NPWS operations 48 Threatened species conservation 48 1 Conservation assessment 13 Southern Regional Forest Agreement 49 NSW Biodiversity Strategy 14 Caring for the environment 49 Regional assessments 14 Waste management 49 Wilderness assessment 16 Performance and future directions 50 Assessment of vacant Crown land in north-east New South Wales 19 Managing our built assets 51 Vegetation surveys and mapping 19 Buildings 51 Wetland and river system survey and research 21 Roads and other access 51 Native fauna surveys and research 22 Other park infrastructure 52 Threat management research 26 Thredbo Coronial Inquiry 53 Cultural heritage research 28 Performance and future directions 54 Conservation research and assessment tools 29 Managing site use in protected areas 54 Performance and future directions 30 Performance and future directions 54 Contributing to communities 55 2 Conservation planning -

Appendix a Consultation

Biodiversity Assessment Report White Rock Wind Farm Modification APPENDIX A CONSULTATION 16 – 321 WRWF BAR Final v2 A‐I Biodiversity Assessment Report White Rock Wind Farm Modification APPENDIX B SPECIES LISTS 16 – 321 WRWF BAR Final v2 B‐I Scientific name Family Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10 Q11 Q12 Q13 Q14 Q15 Q16 Q17 Q18 Q19 Q20 Q21 Q22 Q23 Q24 Q25 Q26 Q27 Q28 Q29 Q30 Q31 Q32 Q33 Q34 Q35 Q36 Q37 Q38 Q39 Q40 Q41 Q42 Q43 Q44 Q45 Q46 Tricoryne elatior Anthericaceae X Dichopogon fimbritus Anthericaceae XX X *Cyclospermum leptophyllum Apiaceae X X X X X X X Daucus glochidiatus Apiaceae XXXXXXXXXXX Hydrocotyle laxiflora Araliaceae X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X Bulbine bulbosa Asphodelaceae X XX X X *Cirsium vulgare Asteraceae X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X Taraxacum officinale Asteraceae X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X *Sonchus oleraceus Asteraceae X X X X X X X *Conyza bonariensis Asteraceae X X X X X X X X X X X X Vittadinia muelleri Asteraceae XX Euchiton involucratus Asteraceae X XXX Brachyschome nova‐angelica Asteraceae X XXXX X Ammobium alatum Asteraceae X X X X X X *Hypochaeris radicata Asteraceae X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X *Sonchus asper Asteraceae X X X X X X X X X X X X *Carthamus lanatus Asteraceae X X *Bidens pilosa Asteraceae X X X X X X Chrysocephalum apiculatum Asteraceae X XX Senecio diaschides Asteraceae XX XX Cymbonotus lasonianus Asteraceae XX X Calotis cuneifolia Asteraceae XXX X X *Tagetes minuta Asteraceae XX X X *Centaurea solstitialis Asteraceae XX Calotis -

Vegetation and Floristics of Butterleaf National Park, Butterleaf State Conservation Area and the Bezzants Lease

Vegetation and Floristics of Butterleaf National Park, Butterleaf State Conservation Area and the Bezzants Lease Dr John T. Hunter May 2011 23 Kendall Rd, Invergowrie NSW, 2350 Ph. & Fax: (02) 6775 2452 Email: [email protected] A Report to the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service & the Nature Conservation Trust of NSW i Vegetation of Butterleaf & Bezzants Lease Summary The vegetation of the Butterleaf National Park and State Conservation Area and Bezzant’s Lease is described and mapped (scale 1:25 000). Nine communities and three sub-associations are defined based on classification (Kulczynski association). These eight communities and three sub-associations were mapped based on ground truthing, air photo interpretation and landform. The communities described and their status is: Floristic Community Area Reservation Status C1a: Eucalyptus radiata – E. Not listed as a community of concern though 1,875 ha campanulata – E. obliqua likely a unique association within the area. C1b: Eucalyptus obliqua – E. Not listed as a community of concern. 263 ha brunnea – E. saligna C1c: Eucalyptus campanulata Not listed as a community of concern. 250 ha – E. obliqua – E. saligna C2: Eucalyptus acaciiformis – Likely to be included as an Endangered Angophora floribunda Ecological Community within the Montane 8.7 ha Peatlands and Swamps determination of the TSC Act. C3: Eucalyptus caliginosa – Not listed as a community of concern though E. bridgesiana – E. 433 ha likely a unique association within the area. laevopinea C4: Eucalyptus nova-anglica Would fall within the Endangered Ecological – E. acaciiformis – E. 39.8 ha Community New England Peppermint subtilior Woodland on the TSC and EPBC Acts. -

Conference Proceedings

A Conference on Restoring Ecological Processes, Ecosystems and Landscapes in a Changing World 5-9 February 2017, Armidale NSW Australia CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS www.conferencecompany.com.au/revegconf2017 These conference proceedings are published by Ecosystem Management, School of Environmental and Rural Science at the University of New England, Armidale, NSW, 2351. The papers contained within these proceedings were presented during Restore, Regenerate, Revegetate: A Conference on Restoring Ecological Processes, Ecosystems and Landscapes in a Changing World, held at the University of New England from 5–9 February 2017. The views and interpretations expressed in these papers are those of the authors of the papers published in these proceedings and do not represent the views of the Editor, the Conference Organising Committee or the University of New England. Whilst papers were subjected to review by at least two anonymous reviewers, accuracy of information and the content of papers remains the responsibility of the authors. Copyright remains with the authors. Papers may be reproduced in part or whole with permission from the authors and appropriate citation of these proceedings. Citation These proceedings may be cited as: Smith, R. (editor) (2018) Proceedings of Restore, Regenerate, Revegetate: A Conference on Restoring Ecological Processes, Ecosystems and Landscapes in a Changing World. Held at the University of New England, Armidale, from 5–9 February 2017 (Ecosystem Management, School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales, Australia). Available at: https://www.une.edu.au/about-une/academic-schools/school-of-environmental-and-rural-science/ers- news-and-events/restore-regenerate-revegetate-conference-2017 ISBN: 978-1-921 597-76-3 Acknowledgements The editor would like to thank the authors and reviewers of the papers published in these proceedings, the Conference Organising Committee and the delegates that attended the conference and made it so successful. -

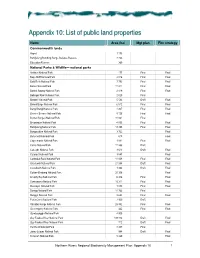

List of Public Land Properties

Appendiix 10: Liist of publliic lland propertiies Name Area (ha) Mgt plan Fire strategy Commonwealth lands Airport 1 175 Bundjalung Bombing Range Defense Reserve 2 233 Education Reserve 360 National Parks & Wildlife— national parks Arakwal National Park 177 Final Final Bago Bluff National Park 4 016 Final Final Bald Rock National Park 7 793 Final Final Barool National Park 11 211 Final Final Basket Swamp National Park 2 819 Final Final Bellinger River National Park 2 829 Final Bindarri National Park 5 584 Draft Final Biriwal Bulga National Park 6 512 Final Final Bongil Bongil National Park 4 207 Final Final Boonoo Boonoo National Park 5 126 Final Final Border Ranges National Park 31 861 Final Broadwater National Park 4 055 Final Final Bundjalung National Park 18 898 Final Final Bungawalbin National Park 3 722 Final Butterleaf National Park 618 Final Capoompeta National Park 1 881 Final Final Carrai National Park 11 366 Draft Cascade National Park 3 613 Draft Final Cataract National Park 3 847 Final Cathedral Rock National Park 11 008 Final Final Chaelundi National Park 21 048 Draft Final Coorabakh National Park 1 364 Draft Final Cottan–Bimbang National Park 20 356 Final Crowdy Bay National Park 6 436 Final Final Cunnawarra National Park 16 311 Final Final Dooragan National Park 1 070 Final Final Dorrigo National Park 11 762 Final Dunggir National Park 2 623 Final Final Fortis Creek National Park 7 909 Draft Gibraltar Range National Park 25 382 Final Final Goonengerry National Park 442 Final Final Gumbaynggirr National Park 4 905 Guy Fawkes -

Developing Cross-Cultural Knowledge (‘Right Way’ Science) to Support Indigenous Cultural Fire Management

University of New England Developing cross-cultural knowledge (‘right way’ science) to support Indigenous cultural fire management Michelle Beverley McKemey B.Sc. University of Queensland, B.Sc. (Hons) La Trobe University A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of New England School of Environmental and Rural Science University of New England November 2020 Certification of Thesis I certify that the substance of this thesis has not been submitted for any degree and is not currently being submitted for any other degree or qualification. I certify that, any assistance received in preparing this thesis, and all resources used, have been acknowledged in this thesis. 27/11/20 _______________________ ___________________ Signature of Candidate Date ii Abstract For millennia, Indigenous peoples have maintained relationships with their environments and managed resources through complex cultural systems. Over the last few centuries, in settler colonial nations, this connection has been and continues to be disrupted. In some areas, Indigenous cultural fire management was prevented and replaced with Western fire strategies such as fire suppression, exclusion and hazard reduction. Despite this, a global movement has begun to restore and renew Indigenous cultural fire management. This thesis investigates ways in which Indigenous rangers and Western scientists can work together to co-produce cross-cultural knowledge (‘right way’ science) to support and provide documented evidence for the benefits and challenges of Indigenous cultural fire management. Indigenous cultural fire management has been re-established at the landscape scale across large areas of northern and central Australia. In southeast Australia, a renewal of Indigenous cultural fire management is underway. -

Four Wheel Drive Adventures Across Australia

FOUR WHEEL DRIVE ADVENTURES ACROSS AUSTRALIA A resource containing interesting destinations, sights, activities, four wheel driving tracks and camping information in Australia. Copyright All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means now known or to be invented, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system without written permission from the author or publisher, except for the brief inclusion of quotation in a review. Disclaimer Every effort has been made to make this book as complete and as accurate as possible, but no warranty or fitness is implied. The information provided is on an “as is” basis. The author and the publisher shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damages arising from the information contained in this book. ISBN 978 0 646 49401 2 Copyright © 2008 by Klara Slabenak Author: Slabenak, Klara. Title: Four wheel drive adventures across Australia / Klara Slabenak. Edition: 1st ed. ISBN: 9780646494012 (pbk.) Subjects: Motor vehicles--Australia--Recreational use Four-wheel drive vehicles--Australia Australia--Guidebooks Australia--Maps, Tourist. Dewey Number: 919.40463 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................1 PLANNING LEAVE..............................................................................................................................2 -

White Rock Wind Farm - Project Approval MP10 160 Modification Application No

White Rock Wind Farm - Project Approval MP10_160 Modification Application No. 4 - Alternative Grid Connection Appendix 3A Biodiversity Assessment Prepared by Environmental Assessments, November 2016 White Rock Wind Farm – Environmental Assessment Report WR-PM-REP-0017 December 2017 BIODIVERSITY (FLORA & FAUNA) ASESSMENT WHITE ROCK WIND FARM Modification Application for ALTERNATIVE GRID CONNECTION AT 330 kV NOVEMBER, 2016 Prepared for WHITE ROCK WIND FARM Pty Ltd By DANIEL O’BRIEN ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENTS PTY LIMITED ECOLOGICAL, BUSHFIRE & CULTURAL HERITAGE CONSULTANCY P.O. BOX 314, GOSFORD, 2250 PH: 0405 585 557 Email: [email protected] I acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which I work and pay my respects to Elders past and present. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AUTHOR STATEMENT IN RESPECT OF STATE LICENCING REQUIREMENTS & APPROVALS 1.0 INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND FIGURE 1 - WHITE ROCK WIND FARM – ALTERNATIVE GRID CONNECTION – 132KV LINE ROUTE AND SUBSTATION LOCATION 2.0 BIOREGIONAL CONTEXT 3.0 LEGISLATIVE & STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS 3.1 OVERVIEW OF RELEVANT REQUIREMENTS 3.2 THREATENED SPECIES CONSERVATION ACT 3.3 NOXIOUS WEEDS ACT 3.4 STATE ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING POLICIES 3.5 ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION & BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION ACT, 1999 3.6 COMMONWEALTH / FEDERAL INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS 4.0 EXISTING DEGREE OF DISTURBANCE 5.0 THE PROPOSAL 6.0 METHODOLOGIES TABLE 6-1 DETAILS OF SURVEY TIMES 6.1 VEGETATION & FLORISTICS SURVEY METHODOLOGIES FIGURE 6.1 – SURVEY LOCATIONS AND THREATENED SPECIES LOCATIONS 6.2 FAUNA-FIELD ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGIES 6.2.1 HABITAT SEARCHES 6.2.2 CONSTRAINTS EXPERIENCED 7.0 THREATENED FLORA & FAUNA SPECIES FOR THE INVERELL-GLEN INNES AREA & ENVIRONS TABLE 7-1 THREATENED SPECIES OF FLORA TABLE 7-2 THREATENED SPECIES OF FAUNA 2 Page Biodiversity (Flora & Fauna) Assessment. -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES

405 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES NewNumb Souther Wales 21 Friday, 6 February 2004 Published under authority by the Government Printing Service LEGISLATION Proclamation Proclamations under the Evidence Legislation AmendmentNew South Wales(Accused Child Detainees) Act 2003 No 57 New South Wales , Governor I, Professor Marie Bashir AC, Governor of the State of New South Wales, with Proclamationthe advice of the Executive Council, and in pursuance of section 2 of the Evidence Legislation Amendment (Accused Child Detainees) Act 2003, do, by underthis my the Proclamation, appoint 9 February 2004 as the day on which that Act Proclamationcommences. SignedEvidence and sealedLegislation at Sydney, Amendment this (Accusedday of Child Detainees) 2004. Act 2003 No 57 under the By Her Excellency’s Command, Evidence Legislation Amendment (Accused Child Detainees) Act 2003 No 57 MARIE BASHIR,, GovernorGovernor I, Professor Marie Bashir AC, Governor of the State of New South Wales, with the advice of the Executive Council, and in pursuance of section 2 of the Evidence Legislation Amendment (Accused Child Detainees)Attorney Act 2003, Governor General, do, by this my Proclamation, appoint 9 February 2004 as the day on which that Act commences.I, Professor Marie Bashir AC,GOD Governor SAVE THEof the QUEEN! State of New South Wales, with Signedthe advice and ofsealed the atExecutive Sydney, Council,this 4th day and of in February pursuance 2004. of section 2 of the EvidenceSigned and Legislation sealed at Sydney, Amendment this (Accused Childday Detainees)of Act 2003 2004., do, by this my Proclamation, appoint 9 February 2004 as the day on which that Act commences.