BSTE744 2020.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hungary & Transylvania

Although we had many exciting birds, the ‘Bird of the trip’ was Wallcreeper in 2015. (János Oláh) HUNGARY & TRANSYLVANIA 14 – 23 MAY 2015 LEADER: JÁNOS OLÁH Central and Eastern Europe has a great variety of bird species including lots of special ones but at the same time also offers a fantastic variety of different habitats and scenery as well as the long and exciting history of the area. Birdquest has operated tours to Hungary since 1991, being one of the few pioneers to enter the eastern block. The tour itinerary has been changed a few times but nowadays the combination of Hungary and Transylvania seems to be a settled and well established one and offers an amazing list of European birds. This tour is a very good introduction to birders visiting Europe for the first time but also offers some difficult-to-see birds for those who birded the continent before. We had several tour highlights on this recent tour but certainly the displaying Great Bustards, a majestic pair of Eastern Imperial Eagle, the mighty Saker, the handsome Red-footed Falcon, a hunting Peregrine, the shy Capercaillie, the elusive Little Crake and Corncrake, the enigmatic Ural Owl, the declining White-backed Woodpecker, the skulking River and Barred Warblers, a rare Sombre Tit, which was a write-in, the fluty Red-breasted and Collared Flycatchers and the stunning Wallcreeper will be long remembered. We recorded a total of 214 species on this short tour, which is a respectable tally for Europe. Amongst these we had 18 species of raptors, 6 species of owls, 9 species of woodpeckers and 15 species of warblers seen! Our mammal highlight was undoubtedly the superb views of Carpathian Brown Bears of which we saw ten on a single afternoon! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Hungary & Transylvania 2015 www.birdquest-tours.com We also had a nice overview of the different habitats of a Carpathian transect from the Great Hungarian Plain through the deciduous woodlands of the Carpathian foothills to the higher conifer-covered mountains. -

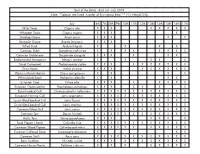

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Magnificent Magpie Colours by Feathers with Layers of Hollow Melanosomes Doekele G

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb174656. doi:10.1242/jeb.174656 RESEARCH ARTICLE Magnificent magpie colours by feathers with layers of hollow melanosomes Doekele G. Stavenga1,*, Hein L. Leertouwer1 and Bodo D. Wilts2 ABSTRACT absorption coefficient throughout the visible wavelength range, The blue secondary and purple-to-green tail feathers of magpies are resulting in a higher refractive index (RI) than that of the structurally coloured owing to stacks of hollow, air-containing surrounding keratin. By arranging melanosomes in the feather melanosomes embedded in the keratin matrix of the barbules. barbules in more or less regular patterns with nanosized dimensions, We investigated the spectral and spatial reflection characteristics of vivid iridescent colours are created due to constructive interference the feathers by applying (micro)spectrophotometry and imaging in a restricted wavelength range (Durrer, 1977; Prum, 2006). scatterometry. To interpret the spectral data, we performed optical The melanosomes come in many different shapes and forms, and modelling, applying the finite-difference time domain (FDTD) method their spatial arrangement is similarly diverse (Prum, 2006). This has as well as an effective media approach, treating the melanosome been shown in impressive detail by Durrer (1977), who performed stacks as multi-layers with effective refractive indices dependent on extensive transmission electron microscopy of the feather barbules the component media. The differently coloured magpie feathers are of numerous bird species. He interpreted the observed structural realised by adjusting the melanosome size, with the diameter of the colours to be created by regularly ordered melanosome stacks acting melanosomes as well as their hollowness being the most sensitive as optical multi-layers. -

Warm Temperatures During Cold Season Can Negatively Affect Adult Survival in an Alpine Bird

Received: 28 February 2019 | Revised: 5 September 2019 | Accepted: 9 September 2019 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.5715 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Warm temperatures during cold season can negatively affect adult survival in an alpine bird Jules Chiffard1 | Anne Delestrade2,3 | Nigel Gilles Yoccoz2,4 | Anne Loison3 | Aurélien Besnard1 1Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (EPHE), Centre d'Ecologie Fonctionnelle Abstract et Evolutive (CEFE), UMR 5175, Centre Climate seasonality is a predominant constraint on the lifecycles of species in alpine National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), PSL Research University, and polar biomes. Assessing the response of these species to climate change thus Montpellier, France requires taking into account seasonal constraints on populations. However, interac- 2 Centre de Recherches sur les Ecosystèmes tions between seasonality, weather fluctuations, and population parameters remain d'Altitude (CREA), Observatoire du Mont Blanc, Chamonix, France poorly explored as they require long‐term studies with high sampling frequency. This 3Laboratoire d'Ecologie Alpine study investigated the influence of environmental covariates on the demography of a (LECA), CNRS, Université Grenoble Alpes, Université Savoie Mont Blanc, corvid species, the alpine chough Pyrrhocorax graculus, in the highly seasonal environ- Grenoble, France ment of the Mont Blanc region. In two steps, we estimated: (1) the seasonal survival 4 Department of Arctic and Marine of categories of individuals based on their age, sex, etc., (2) the effect of environ- Biology, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway mental covariates on seasonal survival. We hypothesized that the cold season—and more specifically, the end of the cold season (spring)—would be a critical period for Correspondence Jules Chiffard, CEFE/CNRS, 1919 route de individuals, and we expected that weather and individual covariates would influence Mende, 34090 Montpellier, France. -

Pica Pica L.) - an Assessment with the Classification Methods

Kirazli et al.: The relationship between parental defense intensity and nest site characteristics in Eurasian magpie - 1293 - THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PARENTAL DEFENSE INTENSITY AND NEST SITE CHARACTERISTICS IN EURASIAN MAGPIE (PICA PICA L.) - AN ASSESSMENT WITH THE CLASSIFICATION METHODS KIRAZLI, C.1* – KAN KILINÇ, B.2 – YAMAÇ, E.3 1Abant İzzet Baysal University, Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Sciences, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Management, 14280 Bolu, Turkey 2Anadolu University, Science Faculty, Department of Statistics, 26470 Eskişehir, Turkey e-mail: [email protected] 3Anadolu University, Science Faculty, Biology Department, 26470 Eskişehir, Turkey e-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] (Received 16th Jan 2017; accepted 20th Mar 2017) Abstract. Nest defense behavior varies among species and depends on different factors. However little is known of the influence of urbanization and nest characteristics on the nest defense intensity as parental investment of the bird species. We observe the Eurasian magpie Pica pica nests to evaluate their nest defense behavior among those factors including urbanization degree of habitat, and nest characteristics such as nest volume, presence/absence of roof, offspring size and the number of offspring reduction for each breeding stages (incubation, early brooding and post brooding stage). To investigate the relationship between the nest defense behavior of Eurasian magpie and a set of those factors we used classification trees, binary logistic regression and random forest. According to our results nest defense strategies can be temporally changed primarily according to the nest volume with the auxiliary agents mostly a reduction of offspring number, which indicates parental capacities and offspring conditions could shape strongly their own nest defense strategies. -

A Guide to Beijing's Common Birds

A Guide To Beijing’s Common Birds The author birding in the Temple of Heaven Park, one of the best sites in central Beijing, especially during migration season. Beijing is a brilliant place to watch birds. More than 460 different types have been recorded in the Chinese capital. And, even inside the 2nd Ring Road, birds can be found! Here is a short guide to 26 of the most common birds that can be found in central Beijing’s parks and green spaces. During migration season (Spring and Autumn), many more species will be possible. 1. Eurasian Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus, 红隼) Eurasian Kestrel. Breeds in small numbers in the city. Eats small rodents (mice, voles) and small birds. Can see ultra-violet! 2. Spotted Dove (Streptopelia chinensis, 珠颈斑鸠) Spotted Dove is common in parks and gardens. Often on the ground. 3. Hoopoe (Upupa epops, 戴胜) The Hoopoe is one of Beijing’s most spectactular birds. It raises its crest when excited or alarmed. 4. Grey-capped Pygmy Woodpecker (Yungipicus canicapillus, 星头啄木鸟) Grey-capped Pygmy Woodpecker is Beijing’s smallest woodpecker. 5. Great Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocopos major, 大斑啄木鸟) Great Spotted Woodpecker. Common in and around Beijing. 6. Grey-headed Woodpecker (Picus canus, 灰头绿啄木鸟) The Grey-headed Woodpecker is common in open woodland and parks. Likes to feed on the ground. Ants are its favourite food! 7. Azure-winged Magpie (Cyanopica cyanus, 灰喜鹊) The Azure-winged Magpie is sociable and often seen in small noisy flocks. 8. Red-billed Blue Magpie (Urocissa erythrorhyncha, 红嘴蓝鹊) The spectacular Red-billed Blue Magpie is a resident in some of the larger parks. -

Evolution of Corvids and Their Presence in the Neogene and the Quaternary in the Carpathian Basin

Ornis Hungarica 2020. 28(1): 121–168. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2020-0009 Evolution of Corvids and their Presence in the Neogene and the Quaternary in the Carpathian Basin Jenő (Eugen) KESSLER Received: September 09, 2019 – Revised: February 12, 2020 – Accepted: February 18, 2020 Kessler, J. (E.) 2020. Evolution of Corvids and their Presence in the Neogene and the Quater- nary in the Carpathian Basin. – Ornis Hungarica 28(1): 121–168. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2020-0009 Abstract: Corvids are the largest songbirds in Europe. They are known in the avian fauna of Europe from the Miocene, the beginning of the Neogene, and are currently represented by 11 species. Due to their size, they occur more frequently among fossilized material than other types of songbirds, and thus have been examined to the largest extent. In the current article, we present their known evolution and their fossilized taxa in Europe and examine the osteology of extant species. Keywords: Corvidae, Neogene, Quaternary, Europe, Carpathian Basin, osteology Összefoglalás: A varjúfélék a legnagyobb termetű, Európában is elterjedt énekesmadarak. A kontinens madárfau- nájában a neogén elejétől, a miocénból ismertek, és jelenleg 11 fajjal vannak képviselve. Termetük következtében gyakrabban előfordulnak a fosszilis anyagban, mint a többi énekesmadár típus, és ennek következtében nagyobb mértékben is tanulmányozták őket. Jelen tanulmányban bemutatjuk az ismert európai evolúciójukat és fosszilis taxonjaikat, és foglalkozunk a recens fajok csonttanával is. Kulcsszavak: Corvidae, neogén, negyedidőszak, Európa, Kárpát-medence, csonttan Department of Paleontology, Eötvös Loránd University, 1117 Budapest, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/c, Hungary, e-mail: [email protected] Introduction About half of the current avian species – if not more – consists of songbirds, which are dis- tributed all around the world apart from Antarctica with a large number of specimens. -

Gear for a Big Year

APPENDIX 1 GEAR FOR A BIG YEAR 40-liter REI Vagabond Tour 40 Two passports Travel Pack Wallet Tumi luggage tag Two notebooks Leica 10x42 Ultravid HD-Plus Two Sharpie pens binoculars Oakley sunglasses Leica 65 mm Televid spotting scope with tripod Fossil watch Leica V-Lux camera Asics GEL-Enduro 7 trail running shoes GoPro Hero3 video camera with selfie stick Four Mountain Hardwear Wicked Lite short-sleeved T-shirts 11” MacBook Air laptop Columbia Sportswear rain shell iPhone 6 (and iPhone 4) with an international phone plan Marmot down jacket iPod nano and headphones Two pairs of ExOfficio field pants SureFire Fury LED flashlight Three pairs of ExOfficio Give- with rechargeable batteries N-Go boxer underwear Green laser pointer Two long-sleeved ExOfficio BugsAway insect-repelling Yalumi LED headlamp shirts with sun protection Sea to Summit silk sleeping bag Two pairs of SmartWool socks liner Two pairs of cotton Balega socks Set of adapter plugs for the world Birding Without Borders_F.indd 264 7/14/17 10:49 AM Gear for a Big Year • 265 Wildy Adventure anti-leech Antimalarial pills socks First-aid kit Two bandanas Assorted toiletries (comb, Plain black baseball cap lip balm, eye drops, toenail clippers, tweezers, toothbrush, REI Campware spoon toothpaste, floss, aspirin, Israeli water-purification tablets Imodium, sunscreen) Birding Without Borders_F.indd 265 7/14/17 10:49 AM APPENDIX 2 BIG YEAR SNAPSHOT New Unique per per % % Country Days Total New Unique Day Day New Unique Antarctica / Falklands 8 54 54 30 7 4 100% 56% Argentina 12 435 -

Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas

sustainability Article Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas Vasilios Liordos 1,* , Jukka Jokimäki 2 , Marja-Liisa Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki 2, Evangelos Valsamidis 1 and Vasileios J. Kontsiotis 1 1 Department of Forest and Natural Environment Sciences, International Hellenic University, 66100 Drama, Greece; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (V.J.K.) 2 Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland; jukka.jokimaki@ulapland.fi (J.J.); marja-liisa.kaisanlahti@ulapland.fi (M.-L.K.-J.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Knowing the ecological requirements of bird species is essential for their successful con- servation. We studied the niche characteristics of birds in managed small-sized green spaces in the urban core areas of southern (Kavala, Greece) and northern Europe (Rovaniemi, Finland), during the breeding season, based on a set of 16 environmental variables and using Outlying Mean Index, a multivariate ordination technique. Overall, 26 bird species in Kavala and 15 in Rovaniemi were recorded in more than 5% of the green spaces and were used in detailed analyses. In both areas, bird species occupied different niches of varying marginality and breadth, indicating varying responses to urban environmental conditions. Birds showed high specialization in niche position, with 12 species in Kavala (46.2%) and six species in Rovaniemi (40.0%) having marginal niches. Niche breadth was narrower in Rovaniemi than in Kavala. Species in both communities were more strongly associated either with large green spaces located further away from the city center and having a high vegetation cover (urban adapters; e.g., Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), European Greenfinch (Chloris Citation: Liordos, V.; Jokimäki, J.; chloris Cyanistes caeruleus Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.-L.; ), Eurasian Blue Tit ( )) or with green spaces located closer to the city center Valsamidis, E.; Kontsiotis, V.J. -

Corvus Monedula -- Linnaeus, 1758

Corvus monedula -- Linnaeus, 1758 ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PASSERIFORMES -- CORVIDAE Common names: Eurasian Jackdaw; Choucas des tours; Jackdaw; Western Jackdaw European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) At both European and EU27 scales this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend appears to be stable, and hence the species does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern within both Europe and the EU27. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Albania; Andorra; Armenia; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Ireland, Rep. of; Italy; Latvia; Liechtenstein; Lithuania; Luxembourg; Macedonia, the former Yugoslav Republic of; Malta; Moldova; Montenegro; Netherlands; Norway; Poland; Portugal; Romania; Russian Federation; Serbia; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Turkey; Ukraine; United Kingdom Vagrant: Faroe Islands (to DK); Iceland; Canary Is. (to ES); Gibraltar (to UK) Population The European population is estimated at 9,930,000-20,800,000 pairs, which equates to 19,900,000-41,700,000 mature individuals. -

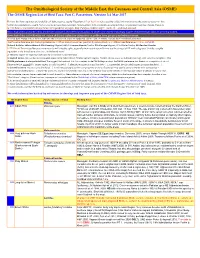

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

A Study of Blue Tits Cyanistes Caeruleus

A CURATE’S EGG: FEEDING BIRDS DURING REPRODUCTION IS ‘GOOD IN PARTS’. A STUDY OF BLUE TITS CYANISTES CAERULEUS AND GREAT TITS PARUS MAJOR by TIMOTHY JAMES EDWARD HARRISON A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Ornithology School of Biosciences The University of Birmingham February 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Food supplementation of birds in gardens is widespread and UK householders have recently been advised to supplement birds throughout the spring and summer. This coincides with reproduction of many avian species and supplementation with specific foods (e.g. live invertebrates) is encouraged to support breeding attempts in gardens. To investigate this further I mimicked food supplementation in gardens by providing two commercial bird foods (peanut cake and mealworms Tenebrio molitor) to blue tits Cyanistes caeruleus and great tits Parus major breeding in woodland in central England from 2006 to 2008. Supplementation advanced laying and reduced the number of young fledged significantly in both species, but provisioning with mealworms during the nestling phase increased apparent survival of fledglings.