Monitoring of Colonies and Provisioning of Rooks with Nest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BSTE744 2020.Pdf

Science of the Total Environment 744 (2020) 140895 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Revisiting an old question: Which predators eat eggs of ground-nesting birds in farmland landscapes? Carolina Bravo a,b,⁎, Olivier Pays b,c, Mathieu Sarasa d,e, Vincent Bretagnolle a,f a Centre d'Etudes Biologiques de Chizé, UMR 7372, CNRS and La Rochelle Université, F-79360 Beauvoir-sur- Niort, France b LETG-Angers, UMR 6554, CNRS, Université d'Angers, 49045 Angers, France c REHABS International Research Laboratory, CNRS-Université Lyon 1-Nelson Mandela University, George Campus, Madiba drive, 6531 George, South Africa d BEOPS, 1 Esplanade Compans Caffarelli, 31000 Toulouse, France e Fédération Nationale des Chasseurs, 92136 Issy-les-Moulineaux cedex, France f LTSER “Zone Atelier Plaine & Val de Sèvre”, CNRS, 79360 Villiers-en-Bois, France HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • Predation probability in artificial nests decreased with camera trap presence. • Corvids might perceive differently plas- ticine and natural eggs. • Camera trap and plasticine eggs combi- nation are recommendable for identify- ing predator. • Corvid predation increased with the abundance of corvid breeders. • Considering social status of corvids is es- sential when assessing corvid abun- dance impact. article info abstract Article history: Nest predation is a major cause of reproductive failure in birds, but predator identity often remains unknown. Ad- Received 12 May 2020 ditionally, although corvids are considered major nest predators in farmland landscapes, whether breeders or Received in revised form 9 July 2020 floaters are involved remains contentious. In this study, we aimed to identify nest predators using artificial nests, Accepted 9 July 2020 and test whether territorial or non-breeders carrion crow (Corvus corone) and Eurasian magpie (Pica pica) were Available online 17 July 2020 most likely involved. -

Hungary & Transylvania

Although we had many exciting birds, the ‘Bird of the trip’ was Wallcreeper in 2015. (János Oláh) HUNGARY & TRANSYLVANIA 14 – 23 MAY 2015 LEADER: JÁNOS OLÁH Central and Eastern Europe has a great variety of bird species including lots of special ones but at the same time also offers a fantastic variety of different habitats and scenery as well as the long and exciting history of the area. Birdquest has operated tours to Hungary since 1991, being one of the few pioneers to enter the eastern block. The tour itinerary has been changed a few times but nowadays the combination of Hungary and Transylvania seems to be a settled and well established one and offers an amazing list of European birds. This tour is a very good introduction to birders visiting Europe for the first time but also offers some difficult-to-see birds for those who birded the continent before. We had several tour highlights on this recent tour but certainly the displaying Great Bustards, a majestic pair of Eastern Imperial Eagle, the mighty Saker, the handsome Red-footed Falcon, a hunting Peregrine, the shy Capercaillie, the elusive Little Crake and Corncrake, the enigmatic Ural Owl, the declining White-backed Woodpecker, the skulking River and Barred Warblers, a rare Sombre Tit, which was a write-in, the fluty Red-breasted and Collared Flycatchers and the stunning Wallcreeper will be long remembered. We recorded a total of 214 species on this short tour, which is a respectable tally for Europe. Amongst these we had 18 species of raptors, 6 species of owls, 9 species of woodpeckers and 15 species of warblers seen! Our mammal highlight was undoubtedly the superb views of Carpathian Brown Bears of which we saw ten on a single afternoon! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Hungary & Transylvania 2015 www.birdquest-tours.com We also had a nice overview of the different habitats of a Carpathian transect from the Great Hungarian Plain through the deciduous woodlands of the Carpathian foothills to the higher conifer-covered mountains. -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Warm Temperatures During Cold Season Can Negatively Affect Adult Survival in an Alpine Bird

Received: 28 February 2019 | Revised: 5 September 2019 | Accepted: 9 September 2019 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.5715 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Warm temperatures during cold season can negatively affect adult survival in an alpine bird Jules Chiffard1 | Anne Delestrade2,3 | Nigel Gilles Yoccoz2,4 | Anne Loison3 | Aurélien Besnard1 1Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (EPHE), Centre d'Ecologie Fonctionnelle Abstract et Evolutive (CEFE), UMR 5175, Centre Climate seasonality is a predominant constraint on the lifecycles of species in alpine National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), PSL Research University, and polar biomes. Assessing the response of these species to climate change thus Montpellier, France requires taking into account seasonal constraints on populations. However, interac- 2 Centre de Recherches sur les Ecosystèmes tions between seasonality, weather fluctuations, and population parameters remain d'Altitude (CREA), Observatoire du Mont Blanc, Chamonix, France poorly explored as they require long‐term studies with high sampling frequency. This 3Laboratoire d'Ecologie Alpine study investigated the influence of environmental covariates on the demography of a (LECA), CNRS, Université Grenoble Alpes, Université Savoie Mont Blanc, corvid species, the alpine chough Pyrrhocorax graculus, in the highly seasonal environ- Grenoble, France ment of the Mont Blanc region. In two steps, we estimated: (1) the seasonal survival 4 Department of Arctic and Marine of categories of individuals based on their age, sex, etc., (2) the effect of environ- Biology, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway mental covariates on seasonal survival. We hypothesized that the cold season—and more specifically, the end of the cold season (spring)—would be a critical period for Correspondence Jules Chiffard, CEFE/CNRS, 1919 route de individuals, and we expected that weather and individual covariates would influence Mende, 34090 Montpellier, France. -

Evolution of Corvids and Their Presence in the Neogene and the Quaternary in the Carpathian Basin

Ornis Hungarica 2020. 28(1): 121–168. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2020-0009 Evolution of Corvids and their Presence in the Neogene and the Quaternary in the Carpathian Basin Jenő (Eugen) KESSLER Received: September 09, 2019 – Revised: February 12, 2020 – Accepted: February 18, 2020 Kessler, J. (E.) 2020. Evolution of Corvids and their Presence in the Neogene and the Quater- nary in the Carpathian Basin. – Ornis Hungarica 28(1): 121–168. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2020-0009 Abstract: Corvids are the largest songbirds in Europe. They are known in the avian fauna of Europe from the Miocene, the beginning of the Neogene, and are currently represented by 11 species. Due to their size, they occur more frequently among fossilized material than other types of songbirds, and thus have been examined to the largest extent. In the current article, we present their known evolution and their fossilized taxa in Europe and examine the osteology of extant species. Keywords: Corvidae, Neogene, Quaternary, Europe, Carpathian Basin, osteology Összefoglalás: A varjúfélék a legnagyobb termetű, Európában is elterjedt énekesmadarak. A kontinens madárfau- nájában a neogén elejétől, a miocénból ismertek, és jelenleg 11 fajjal vannak képviselve. Termetük következtében gyakrabban előfordulnak a fosszilis anyagban, mint a többi énekesmadár típus, és ennek következtében nagyobb mértékben is tanulmányozták őket. Jelen tanulmányban bemutatjuk az ismert európai evolúciójukat és fosszilis taxonjaikat, és foglalkozunk a recens fajok csonttanával is. Kulcsszavak: Corvidae, neogén, negyedidőszak, Európa, Kárpát-medence, csonttan Department of Paleontology, Eötvös Loránd University, 1117 Budapest, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/c, Hungary, e-mail: [email protected] Introduction About half of the current avian species – if not more – consists of songbirds, which are dis- tributed all around the world apart from Antarctica with a large number of specimens. -

Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas

sustainability Article Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas Vasilios Liordos 1,* , Jukka Jokimäki 2 , Marja-Liisa Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki 2, Evangelos Valsamidis 1 and Vasileios J. Kontsiotis 1 1 Department of Forest and Natural Environment Sciences, International Hellenic University, 66100 Drama, Greece; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (V.J.K.) 2 Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland; jukka.jokimaki@ulapland.fi (J.J.); marja-liisa.kaisanlahti@ulapland.fi (M.-L.K.-J.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Knowing the ecological requirements of bird species is essential for their successful con- servation. We studied the niche characteristics of birds in managed small-sized green spaces in the urban core areas of southern (Kavala, Greece) and northern Europe (Rovaniemi, Finland), during the breeding season, based on a set of 16 environmental variables and using Outlying Mean Index, a multivariate ordination technique. Overall, 26 bird species in Kavala and 15 in Rovaniemi were recorded in more than 5% of the green spaces and were used in detailed analyses. In both areas, bird species occupied different niches of varying marginality and breadth, indicating varying responses to urban environmental conditions. Birds showed high specialization in niche position, with 12 species in Kavala (46.2%) and six species in Rovaniemi (40.0%) having marginal niches. Niche breadth was narrower in Rovaniemi than in Kavala. Species in both communities were more strongly associated either with large green spaces located further away from the city center and having a high vegetation cover (urban adapters; e.g., Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), European Greenfinch (Chloris Citation: Liordos, V.; Jokimäki, J.; chloris Cyanistes caeruleus Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.-L.; ), Eurasian Blue Tit ( )) or with green spaces located closer to the city center Valsamidis, E.; Kontsiotis, V.J. -

Corvus Monedula -- Linnaeus, 1758

Corvus monedula -- Linnaeus, 1758 ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- PASSERIFORMES -- CORVIDAE Common names: Eurasian Jackdaw; Choucas des tours; Jackdaw; Western Jackdaw European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) At both European and EU27 scales this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend appears to be stable, and hence the species does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern within both Europe and the EU27. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Albania; Andorra; Armenia; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Ireland, Rep. of; Italy; Latvia; Liechtenstein; Lithuania; Luxembourg; Macedonia, the former Yugoslav Republic of; Malta; Moldova; Montenegro; Netherlands; Norway; Poland; Portugal; Romania; Russian Federation; Serbia; Slovakia; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Turkey; Ukraine; United Kingdom Vagrant: Faroe Islands (to DK); Iceland; Canary Is. (to ES); Gibraltar (to UK) Population The European population is estimated at 9,930,000-20,800,000 pairs, which equates to 19,900,000-41,700,000 mature individuals. -

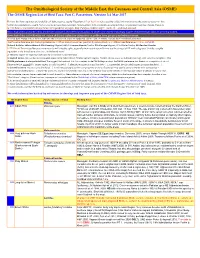

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

A Study of Blue Tits Cyanistes Caeruleus

A CURATE’S EGG: FEEDING BIRDS DURING REPRODUCTION IS ‘GOOD IN PARTS’. A STUDY OF BLUE TITS CYANISTES CAERULEUS AND GREAT TITS PARUS MAJOR by TIMOTHY JAMES EDWARD HARRISON A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Ornithology School of Biosciences The University of Birmingham February 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Food supplementation of birds in gardens is widespread and UK householders have recently been advised to supplement birds throughout the spring and summer. This coincides with reproduction of many avian species and supplementation with specific foods (e.g. live invertebrates) is encouraged to support breeding attempts in gardens. To investigate this further I mimicked food supplementation in gardens by providing two commercial bird foods (peanut cake and mealworms Tenebrio molitor) to blue tits Cyanistes caeruleus and great tits Parus major breeding in woodland in central England from 2006 to 2008. Supplementation advanced laying and reduced the number of young fledged significantly in both species, but provisioning with mealworms during the nestling phase increased apparent survival of fledglings. -

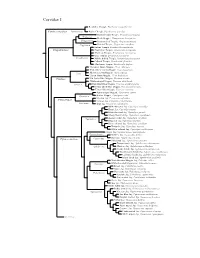

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

Songbird Remix CORVUS CORVUS Contents

Avian Models for 3D Applications by Ken Gilliland 1 Songbird ReMix CORVUS CORVUS Contents Manual Introduction 3 Overview and Use 3 Where to Find your birds and Poses 4 One Folder to Rule them All 4 Physical-based Rendering 5 Posing and Shaping Tips 5 Field Guide Field Guide List 6 Ravens Australian Raven 7 Common Raven 9 White-necked Raven 12 Crows American Crow 14 Eurasian or Western Jackdaw 18 ‘Alala - Hawaiian Crow 21 Rook 25 Credits and Resources 29 Copyrighted 2013-20 by Ken Gilliland www.SongbirdReMix.com Opinions expressed on this booklet are solely that of the author, Ken Gilliland, and may or may not reflect the opinions of the publisher. 2 Songbird ReMix CORVUS CORVUS Introduction Ravens and crows through the ages have represented the darker and sometimes, playful elements in human cultures. In Irish mythology, crows are associated with Morrigan, the goddess of war and death while the Norse believed that ravens carry news to the god Odin about the mortal world. In Hawaiian, Aboriginal and Native American cultures, crows and ravens are believed to be embodiments of ancestor’s spirits or sometimes “The Trickster”; a deity that breaks the rules of the gods or nature, sometimes maliciously but usually with ultimately positive effects. The collective name for a group of crows is a “murder of crows”. Ravens and crows are now considered to be among the world's most intelligent animals. Recent research has found some species capable of not only tool use but also tool construction. The set is located within the Animals : Songbird ReMix folder. -

Can Birds Think?

1 Can birds think? © John Erritzøe 2015 MY TAME PARROT Many years ago, we had a visit from a married couple of which the husband was a, clearly sexist, pastor. As soon as he came into the room and saw our parrot, which at that time was still in a cage, he exclaimed quite spontaneously: “God has created the parrot, so we humans can learn what empty woman talk is.” The Reverend then gave our bird no more attention. While we now sat around the table and talked about the weather the clergyman's wife went to the parrot and studied it from all sides, while Jakob, as we called the parrot, studied her through the cage bars with equal interest. None of them said a word. After about 15- minutes of silence Jakob finally said with a clear and questioning voice: “what are you glaring at”? The priest's complexion became pale and during the rest of the visit he was conspicuously silent. Was Jakob's statement just a random parroting of something he had previously heard, or was there really a form of thought behind it’s issues? Of course, it might have been a coincidence that Jakob said the phrase that he did. The strangest thing was, however, that we never before or after this episode heard him say the same sentence: Only this one time. A more likely explanation might be that Jakob had previously heard another human say "what are you glaring at" in similar circumstances and upon experiencing his first subsequent analogous situation had his memory evoked of precisely this sentence.