Fossil Forests Preserved in Volcanic Ash and Lava at Ihumatao and Takapuna, Auckland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A U C K L a N D C O U N C

A U C K L A N D C O U N C I L Decision following the hearing of an application for resource consent SUBJECT: Application for resource consent under section 88 of the Resource Management Act 1991 by Peers Brown Miller Ltd to remove two notable pohutukawa trees from within a grove at 8 Minnehaha Avenue, Takapuna held on Monday, 17 November 2014 commencing at 9.31am CONSENT, PURSUANT TO SECTIONS 104 AND 104B OF THE RESOURCE MANAGEMENT ACT, IS REFUSED. THE FULL DECISION IS SET OUT BELOW Hearing Panel: The Application was heard by Hearings Commissioners consisting of: Ms Kathleen Ryan (Chairperson) Mr Hugh Leersnyder Council Officers: Ms Sally Robins Senior Planner Mr Steven Krebs Arborist Ms Rebecca Fogel Built Heritage Specialist Ms Melissa Democracy Advisor - Hearings Warmenhoven APPEARANCES: For the applicant: Peers Brown Miller Ltd on behalf of N M Growth Limited, represented by: Andrew Braggins (legal counsel) calling the following as witnesses: Sarah Aynsley - Applicant Roger Twiname – Structural Engineer Ross Thurlow – Structural Engineer Rob Pryor – Landscape Architect Gerard Mostert - Arborist Submitters: Maurice Norton for Environment Takapuna Inc Mike Smith Peter Cunningham Hueline Massey for the Tree Council: and Chris Boucher, Arborist, as witness 1 APPLICATION DESCRIPTION Application and Property Details Application Number (s): LX2138339 Site Address: 8 Minnehaha Avenue, Takapuna Applicant's Name: Peers Brown Miller Ltd on behalf of N M Growth Ltd Lodgement Date: 0 August 2013 Notification date: 24 June 2014 Submissions closed -

Changes to the Marine Biota of the Auckland Harbour, by F. I

TANE 29, 1983 CHANGES TO THE MARINE BIOTA OF THE AUCKLAND HARBOUR by F. I. Dromgoole* and B. A. Fostert * Department of Botany, University of Auckland, Private Bag, Auckland t Department of Zoology, University of Auckland, Private Bag, Auckland SUMMARY The history of study of the marine biota of Auckland Harbour is briefly reviewed, and it is concluded that there is insufficient documented information to make quantitative assessment of changes that have resulted from reclamation, sedimentation and pollution that have occurred with the development of the Port of Auckland. Losses of mangrove and saltmarsh communities are indisputable, but causes of declines in populations of Zostera, Pomatoceros and Perna are not so clear. On the other hand, a number of species have been introduced, and circumstantial evidence suggests these adventives have arrived as ship- fouling. Cases discussed are Codium fragile tomentosoides, Colpomenia bullosa, Limaria orientalis and Sagartia luciae. The most conspicuous newcomer, the oyster Crassostrea gigas, may have been deliberately introduced. INTRODUCTION Regular use of the Auckland Harbour by European ships stems from the early 1800s, so there has been ample opportunity for the introduction of adventive fouling species. Maritime reclamation in Auckland Harbour dates back to about 1860 when shores near the commercial centre were filled and extended as wharves and breakwaters. Modification of habitats and inhabitants of the harbour has now been going on for more than 120 years, but scientific study of them has been of much shorter duration. In this paper we wish to document some additions and alterations to the marine biology. Auckland Harbour has three parts (see Fig. -

Devonport Bayswater Hauraki

Devonport Routes Fare Zones 801 Bayswater Ferry Terminal, Takapuna, Akoranga Station Bayswater 802 Bayswater, Esmonde Rd, Wellesley St, City Centre (Mayoral Dr) & Boundaries (Monday to Friday peak only) Wellsford 806 Stanley Point, Devonport Ferry Terminal Hauraki Omaha 807 Cheltenham, Devonport Ferry Terminal Matakana 814 Devonport Ferry Terminal, Narrow Neck, Takapuna, Warkworth Northern Bus & Ferry Timetable Akoranga Station Devonport to City Ferry Warkworth Bayswater to City Ferry Stanley Bay to City Ferry Waiwera Helensville Hibiscus Coast Your guide to buses and ferries in this area Devonport to Waiheke Island Ferry Orewa Wainui Kaukapakapa Hibiscus Coast Gulf Harbour Waitoki Other timetables available in this area that may interest you Upper North Shore Timetable Routes Albany Waiheke Campbells Bay, Sunnynook, Constellation Lower North Shore 82, 83, 842, 843, 845, 856, 871, 907 Riverhead Milford, Takapuna Hauraki Gulf Takapuna Rangitoto Long Bay, Torbay, Browns Bay, Island 83, 856, 861, 865, 878 Huapai Westgate City 801 802 806 Mairangi Bay Isthmus Waitemata Harbour Britomart Swanson 97B, 97R, 97V, 917, 931, 933, 941, Kingsland Newmarket Beachlands Beach Haven, Birkenhead 942, 966, Beach Haven Ferry, Henderson Birkenhead Ferry Waitakere Panmure New Lynn Waitakere Onehunga 807 814 95B, 95C, 95G, 906, 917, 939, 941, Ranges Otahuhu Botany Glenfield, Bayview, Windy Ridge Birkenhead Ferry Manukau Hillcrest, Northcote 923, 924, 926, 928, 942 Manukau Airport Manukau Harbour North Greenhithe, Unsworth Heights, 120, 901, 906, 907 Wairau -

Unlock Takapuna Framework Plan

Takapuna Framework Plan Anzac Street and Gasometer car parks July 2017 1 2 Contents Mihi .......................................................................... 6 Section four: The Unlock sites ................................... 52 Anzac Street car park ................................................................55 Foreword ................................................................... 9 Gasometer car park ....................................................................56 Executive summary ...................................................10 Section five: Our design thinking ............................... 58 Section one: Introduction ...........................................12 Our design thinking ....................................................................60 A spectacular lake and seaside setting .....................................15 Design principles .........................................................................64 Unlock Takapuna. .........................................................................18 Green Star – Communities ........................................................66 Anzac Street car park ................................................................68 Section two: Vision and goals .................................... 22 Gasometer car park .................................................................... 76 Our vision ..................................................................................... 24 Section six: Delivery ................................................ -

The Sonic Bildungsroman: Coming-Of-Age Narratives in Album Form

The Sonic Bildungsroman: Coming-of-Age Narratives in Album Form Dallas Killeen TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 __________________________________________ Hannah Wojciehowski Department of English Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Chad Bennett Department of English Second Reader Abstract Author: Dallas Killeen Title: The Sonic Bildungsroman: Coming-of-Age Narratives in Album Form Supervising Professors: Hannah Wojciehowski, Ph.D. Chad Bennett, Ph.D. The Bildungsroman, or coming-of-age story, deals with the transitional period of adolescence. Although initially conceived in the novel form, the Bildungsroman has since found expression in various media. This thesis expands the scope of the genre by describing the “sonic Bildungsroman,” or coming-of-age album, and exploring a few key examples of this previously undefined concept. Furthermore, the record as a medium affords musicians narrative agency critical to their identity development, so this project positions the coming- of-age album squarely in the tradition of the Bildungsroman as a tool for self-cultivation. This thesis examines two albums in great detail: Pure Heroine by Lorde and Channel Orange by Frank Ocean. In these records, Lorde and Ocean lyrically, musically, and visually portray their journeys toward self-actualization. While the works show thematic similarities in their respective presentations of the adolescent experience, Lorde and Ocean craft stories colored by their unique identities. In this way, the two albums capture distinct approaches to constructing coming-of-age narratives in album form, yet both represent foundational examples of the genre due to their subject matter, narrative trajectory, and careful composition. From this basis, this project offers a framework for understanding how popular musicians construct coming-of-age stories in their albums—and for understanding how these stories affect us as listeners. -

St Joseph's Catholic School Takapuna

ST JOSEPH’S CATHOLIC SCHOOL –TAKAPUNA SCHOOL PROFILE St. Joseph’s Catholic School is situated at 2 Taharoto Road, Takapuna, immediately adjacent to St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, Presbytery and Hall and accessed via 10 Dominion Street. It is an integrated Catholic Primary School for girls and boys from New Entrants to Year 6, offering education with a Special Catholic Character. The first school, on this site, was St Mary’s Industrial School, started in 1846 and run by Catholic lay people. Our current school commenced in 1893 as one classroom to provide education for the children housed at St. Joseph’s Orphanage. It was run by the Sisters of Mercy who have a continuing association with our school. In 1930, the school was extended to cater for all children of the Takapuna Parish of the Catholic Diocese of Auckland. St. Joseph’s School was integrated as a state school with Special Catholic Character on 16 February 1983. The proprietor of the school is the Catholic Bishop of Auckland. It is one of five Catholic primary schools on Auckland’s North Shore providing for the education of children from Catholic families of the Takapuna and Glenfield parishes, in particular. The Principals of all these schools, plus Rosmini and Carmel Colleges, meet regularly for professional learning and collaboration. The school is made up of The McAuley Administration Centre which includes the school library; the Pompallier Learning Centre which is a recently completed innovative learning environment catering for approximately 380 children; a block of 4 single cell classrooms; the Father David Nolan Hall - a multi- purpose building, and the Mary Thomas Learning Centre. -

Northcote Framework Plan Contents

Northcote Northcote Framework Plan November 2016 Framework Plan Framework Contents Contents .......................................................................................... 3 Section Three: Key moves ......................................... 50 Summary of key moves .................................................................52 Mihi ................................................................................................... 4 Key move one: Town centre – creating a vibrant heart ............56 Foreword ......................................................................................... 7 Summary ..................................................................................... 57 Context ........................................................................................60 Executive summary .................................................... 8 Key move two: Lake Road – creating a great urban street ......80 Momentum is now on Northcote’s side ........................................ 8 Summary ......................................................................................81 Northcote 2030 ......................................................................... 10 Context .........................................................................................81 Section one: Introduction ...........................................12 Key move three: A blue-green way – a network of public open space ...................................................86 Panuku: Who we are and our approach .......................................14 -

Devonport-Takapuna Local Economic Overview 2019

20 MARCH 20 AUCKLAND ECONOMIC OVERVIEWS DEVONPORT- TAKAPUNA ── LOCAL BOARD ECONOMIC OVERVIEW aucklandnz.com/business a 2 | Devonport-Takapuna Local Economic Overview 2019 2 | Document Title – even page header Contents Introduction 1 People and Households 2 Skills 3 Local Economy 4 Employment Zones 5 6 Development trends Economic Development Opportunities 7 Glossary 8 aucklandnz.com/business 3 3 | Document Title – even page header Introduction What is local economic development ATEED’s goal is to support the creation of quality jobs for all Aucklanders and while Auckland’s economy has grown in recent years, the benefits of that growth are not distributed evenly. Local economic development brings together a range of players to build up the economic capacity of a local area and improve its economic future and quality of life for individuals, families and communities. Auckland’s economic development Auckland has a diverse economy. While central Auckland is dominated by financial, insurance and other professional services, parts of south and west Auckland have strengths in a range of manufacturing industries. In other areas, tourism is a key driver and provides a lot of local employment while there are also areas that are primarily residential where residents commute to the city centre or one of the industrial precincts for employment. The Auckland region also has a significant primary sector in the large rural areas to the north and south of the region. The Auckland Growth Monitor1 and Auckland Index2 tell the story behind Auckland’s recent economic growth. While annual GDP growth of 4.3 per cent per year over the last five years is encouraging, we want our economy to be more heavily weighted towards industries that create better quality jobs and generate export earnings. -

New Zealand Transport Agency Additional Waitemata

Attachment A New Zealand Transport Agency Additional Waitemata Harbour Crossing Preliminary Business Case Restrictions of this report This report has been prepared by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER) for the NZ Transport Agency (NZTA) solely for the purposes stated herein and should not be relied upon for any other purpose. We accept no liability to any party should it be used for any purpose other than that for which it was prepared. This Report is strictly confidential and (save to the extent required by applicable law and/or regulation) must not be released to any third party without our express written consent which is at our sole discretion. To the fullest extent permitted by law, PwC accepts no duty of care to any third party in connection with the provision of this Report and/or any related information or explanation (together, the “Information”). Accordingly, regardless of the form of action, whether in contract, tort (including without limitation, negligence) or otherwise, and to the extent permitted by applicable law, PwC accepts no liability of any kind to any third party and disclaims all responsibility for the consequences of any third party acting or refraining to act in reliance on the Information. We have not independently verified the accuracy of information provided to us, and have not conducted any form of audit in respect of NZTA. Accordingly, we express no opinion on the reliability, accuracy, or completeness of the information provided to us and upon which we have relied. The statements and opinions expressed herein have been made in good faith, and on the basis that all information relied upon is true and accurate in all material respects, and not misleading by reason of omission or otherwise. -

Takapuna Including Milford and Hauraki

North Takapuna including Milford and Hauraki f Parnell is Auckland’s Beverly Hills, Takapuna is its Malibu. An address in Takapuna I or Milford signifies prestige and affluence. Life here centres around the two gorgeous beaches – Takapuna and Milford – whether it’s the stunning views from the high-rise apartments that are comparatively new to the area, or being able to step right onto the sand from one of the elegant homes that line the beachfront. Location is everything in these suburbs and parochialism abounds. Tell Milford dwellers that Takapuna has the edge and you’ll get the pointy finger. The closer to the beach, or the more expansive the sea view, the greater the kudos. For those who want the lifestyle without the big beach house, apartments offer resort-style living, with cafés, restaurants and entertainment all within walking distance. Population Profile Population 13,638 % Aged Under 15 Years 14.91 % Aged Over 65 Years 17.66 % European 71.21 % Maori 3.83 % Pacific Peoples 1.41 % Asian 12.95 Who Lives There? The smart, the stylish and the suitably suntanned all live here. Takapuna and Milford are the suburbs that everyone else on this side of the bridge aspires to move to. A stroll along Takapuna beach tells you lots about the locals, whether it’s the gold that adorns the beachgoers or the fabulous homes that abut the beach. In Milford there are affluent families with boating in their blood, and many older people who like the flat walk to the mall and the beach. For colour key, see page 230 North – Takapuna 171 Takapuna North Anywhere along the seaward side of Lake The well-appointed Sunnynook School is one Rd, this country’s high rollers have put down of the largest primaries, with a roll close to 500. -

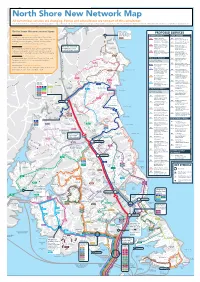

North Shore New Network Map

North Shore New Network Map All current bus services are changing. Ferries and school buses are not part of this consultation The route numbers used are for consultation purposes only, and may not be the final numbers. Bus stop locations will be reviewed once the New Network is finalised. All routes travel in both directions except where arrows indicate. Get to know the new service types N78 will be extended when PROPOSED SERVICES Frequent services area develops BUSWAY SERVICES LOCAL SERVICES Operate on key routes across Auckland. Run at least N78 NX1 Albany to Britomart N12 Stanley Point to every 15 mins during the day (7am – 7pm, 7 days a week), (Lower Albert St), at least Devonport Ferry Terminal and may run less frequently outside of these times. every 10 – 15 mins, 7 days a week, more often during peak N13 Devonport Ferry Terminal to In some cases run more often at peak times. Long Bay Mt Victoria/Cheltenham NX2 Albany to City universities, N21a Northcote Point to Connector services NX to be extended s Rd at least every 10 – 15 mins, han Long Bay Long Bay 7 days a week, more often Smales Farm Station via to Hibiscus Coast Vaug B Regional Park during peak Northcote and Run at least every 30 mins during the day (7am – 7pm, e Ashley a North Shore Hospital Station in the future ch Albany to Newmarket, 7 days a week), and may run less frequently outside R NX3 d Ext Mon to Fri only, at least every N21b Birkenhead Wharf to of these times. -

Takapuna Beach Reserve South Concept Plan

Takapuna Beach Reserve South Concept Plan DRAFT REPORT JULY 2014 Acknowledgements: Devonport-Takapuna Local Board Parks Advisors - Nicki Malone and Matthew Woodside $XFNODQG&RXQFLO3DUNV'HVLJQ7HDP/L]2OGñHOGDQG7ULQD-DVKDUL Neil Coleman, Architectural Sketches and Perspectives (ASAP), Artistic Impressions Auckland Council Environmental Services Unit (Stormwater), Boffa Miskell and AR Civil Consulting (Takapuna Beach Southern Sector - Stormwater Outfalls: Draft Concept Design Report 2012) Contents Section 1: Introduction and background 4.4 Concept plan project area 4: Sanders Avenue 1.1 Introduction 7 4.4.1 Existing site context 36 1.2 Public & stakeholder engagement 7 4.4.2 Concept plan: Sanders Avenue 37 1.3 Time line 8 1.4 Aerial Photography 9 4.5 Concept plan project area 5: Park Avenue 4.5.1 Existing site context 38 Section 2: Site analysis 4.5.2 Concept plan: Park Avenue 39 2.1 Site context 12 2.2 Character imagery 13 Preliminary concept options developed by 2.3 Circulation and built form 14 Auckland Council Stormwater team: 2.4 Cultural heritage 15 4.6 Concept plan project area 6: Rewiti Avenue 2.5 Natural heritage 16 4.6.1 Existing site context 40 2.6 Unitary Plan context 17 4.6.2 Concept plan: Rewiti Avenue 41 4.6.3 Artists impression 43 Section 3: Design guidance 3.1 Design principles 20 4.7 Concept plan project area 7: Ewen Street 3.2 Design guidance for parks and furniture 21 4.7.1 Existing site context 44 4.7.2 Concept plan: Ewen Street 45 Section 4: Concept plans 4.8 Concept plan project area 8: Hauraki Road 4.0 Concept plan