Observation on a Pair of Gray Hawks in Southern Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extreme Variation in the Tails of Adult Harlan’S Hawks

EXTREME VARIATION IN THE TAILS OF ADULT HARLAN’S HAWKS William S. (Bill) Clark Some adult Harlan’s Hawks have tails somewhat similar to this one Bob Dittrick But many others have very different tails, both in color and in markings Harlan’s Hawk type specimen. Audubon collected this adult in 1830 in Louisiana (USA) and described it as Harlan’s Buzzard or Black Warrier - Buteo harlani It is a dark morph, the common morph for this taxon. British Museum of Natural History, Tring Harlan’s Hawk Range They breed in Alaska, Yukon, & ne British Columbia & winter over much of North America. It occurs in two color morphs, dark and light. The AOS considers Harlan’s Hawk a subspecies of Red- tailed Hawk, Buteo jamaicensis harlani, but my paper in Zootaxa advocates it as a species. Clark (2018) Taxonomic status of Harlan’s Hawk Buteo jamaicensis harlani (Aves: Accipitriformes) Zootaxa concludes: “It [Harlan’s Hawk] should be considered a full species based on lack of justification for considering it a subspecies, and the many differences between it and B. jamaicensis, which are greater than differences between any two subspecies of diurnal raptor.” Harlan’s Hawk is a species: 1. Lack of taxonomic justification for inclusion with Buteo jamaicensis. 2. Differs from Buteo jamaicensis by: * Frequency of color morphs; * Adult plumages by color morph, especially in tail pattern and color; * Neotony: Harlan’s adult & juvenile body plumages are almost alike; whereas those of Red-tails differ. * Extent of bare area on the tarsus. * Some behaviors. TYPE SPECIMEN - Upper tail is medium gray, with a hint of rufous and some speckling, wavy banding on one feather, & wide irregular subterminal band. -

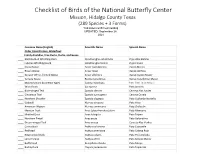

Bird Checklist

Checklist of Birds of the National Butterfly Center Mission, Hidalgo County Texas (289 Species + 3 Forms) *indicates confirmed nesting UPDATED: September 28, 2021 Common Name (English) Scientific Name Spanish Name Order Anseriformes, Waterfowl Family Anatidae, Tree Ducks, Ducks, and Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Pijije Alas Blancas Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Pijije Canelo Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ganso Blanco Ross's Goose Anser rossii Ganso de Ross Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Ganso Careto Mayor Canada Goose Branta canadensis Ganso Canadiense Mayor Muscovy Duck (Domestic type) Cairina moschata Pato Real (doméstico) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Pato Arcoíris Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cerceta Alas Azules Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cerceta Canela Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Pato Cucharón Norteño Gadwall Mareca strepera Pato Friso American Wigeon Mareca americana Pato Chalcuán Mexican Duck Anas (platyrhynchos) diazi Pato Mexicano Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula Pato Tejano Northern Pintail Anas acuta Pato Golondrino Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Cerceta Alas Verdes Canvasback Aythya valisineria Pato Coacoxtle Redhead Aythya americana Pato Cabeza Roja Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Pato Pico Anillado Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Pato Boludo Menor Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Pato Monja Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Pato Tepalcate Order Galliformes, Upland Game Birds Family Cracidae, Guans and Chachalacas Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chachalaca Norteña Family Odontophoridae, -

Comparative Phylogeography and Population Genetics Within Buteo Lineatus Reveals Evidence of Distinct Evolutionary Lineages

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 49 (2008) 988–996 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Comparative phylogeography and population genetics within Buteo lineatus reveals evidence of distinct evolutionary lineages Joshua M. Hull a,*, Bradley N. Strobel b, Clint W. Boal b, Angus C. Hull c, Cheryl R. Dykstra d, Amanda M. Irish a, Allen M. Fish c, Holly B. Ernest a,e a Wildlife and Ecology Unit, Veterinary Genetics Laboratory, 258 CCAH, University of California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA b U.S. Geological Survey Texas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Natural Resources Management, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA c Golden Gate Raptor Observatory, Building 1064 Fort Cronkhite, Sausalito, CA 94965, USA d Raptor Environmental, 7280 Susan Springs Drive, West Chester, OH 45069, USA e Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, One Shields Avenue/Old Davis Road, Davis, CA 95616, USA article info abstract Article history: Traditional subspecies classifications may suggest phylogenetic relationships that are discordant with Received 25 June 2008 evolutionary history and mislead evolutionary inference. To more accurately describe evolutionary rela- Revised 13 September 2008 tionships and inform conservation efforts, we investigated the genetic relationships and demographic Accepted 17 September 2008 histories of Buteo lineatus subspecies in eastern and western North America using 21 nuclear microsatel- Available online 26 September 2008 lite loci and 375-base pairs of mitochondrial control region sequence. Frequency based analyses of mito- chondrial sequence data support significant population distinction between eastern (B. -

Diurnal Birds of Prey of Belize

DIURNAL BIRDS OF PREY OF BELIZE Nevertheless, we located thirty-four active Osprey by Dora Weyer nests, all with eggs or young. The average number was three per nest. Henry Pelzl, who spent the month The Accipitridae of June, 1968, studying birds on the cayes, estimated 75 Belize is a small country south of the Yucatán to 100 pairs offshore. Again, he could not get to many Peninsula on the Caribbean Sea. Despite its small of the outer cayes. It has been reported that the size, 285 km long and 112 km wide (22 963 km2), southernmost part of Osprey range here is at Belize encompasses a great variety of habitats: Dangriga (formerly named Stann Creek Town), a mangrove cays and coastal forests, lowland tropical little more than halfway down the coast. On Mr pine/oak/palm savannas (unique to Belize, Honduras Knoder’s flight we found Osprey nesting out from and Nicaragua), extensive inland marsh, swamp and Punta Gorda, well to the south. lagoon systems, subtropical pine forests, hardwood Osprey also nest along some of the rivers inland. Dr forests ranging from subtropical dry to tropical wet, Stephen M. Russell, author of A Distributional Study and small areas of elfin forest at the top of the highest of the Birds of British Honduras, the only localized peaks of the Maya Mountains. These mountains are reference, in 1963, suspects that most of the birds seen built of extremely old granite overlaid with karst inland are of the northern race, carolinensis, which limestone. The highest is just under 1220 m. Rainfall winters here. -

Breeding Biology of Neotropical Accipitriformes: Current Knowledge and Research Priorities

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 26(2): 151–186. ARTICLE June 2018 Breeding biology of Neotropical Accipitriformes: current knowledge and research priorities Julio Amaro Betto Monsalvo1,3, Neander Marcel Heming2 & Miguel Ângelo Marini2 1 Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia, IB, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil. 2 Departamento de Zoologia, IB, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 08 March 2018. Accepted on 20 July 2018. ABSTRACT: Despite the key role that knowledge on breeding biology of Accipitriformes plays in their management and conservation, survey of the state-of-the-art and of information gaps spanning the entire Neotropics has not been done since 1995. We provide an updated classification of current knowledge about breeding biology of Neotropical Accipitridae and define the taxa that should be prioritized by future studies. We analyzed 440 publications produced since 1995 that reported breeding of 56 species. There is a persistent scarcity, or complete absence, of information about the nests of eight species, and about breeding behavior of another ten. Among these species, the largest gap of breeding data refers to the former “Leucopternis” hawks. Although 66% of the 56 evaluated species had some improvement on knowledge about their breeding traits, research still focus disproportionately on a few regions and species, and the scarcity of breeding data on many South American Accipitridae persists. We noted that analysis of records from both a citizen science digital database and museum egg collections significantly increased breeding information on some species, relative to recent literature. We created four groups of priority species for breeding biology studies, based on knowledge gaps and threat categories at global level. -

North American Buteos with This Charac- Seen by Many Birders but Did Not Return the Next Year

RECOGNIZING HYBRIDS “What is that bird?” How many times have we heard this question or something similar while out birding in a group? The bird in question is often a raptor, shorebird, flycatcher, warbler, or some other hard-to-distinguish bird. Thankfully, there are excellent field guides to help us with these difficult birds, including more- specialized guides for difficult-to-identify families such as raptors, war- blers, gulls, and shore- birds. But when we en- counter hybrids in the field, even the specialty guides are not sufficient. Herein we discuss and present photographs of four individuals that the three of us agree are interspecific hybrids in the genus Buteo. Note: In this article, we follow the age and molt terminology of Howell et al. (2003). Fig. 1. Hybrid Juvenile Hybrid 1 – Juvenile Rough-legged × Swainson’s Hawk Swainson’s × Rough- This hybrid (Figs. 1 & 2) was found by MR, who first noticed it on the legged Hawk. Wing shape morning of 19 November 2002 near Fort Worth, Texas. The hunting hawk is like that of Swainson’s was seen well and rather close up, both in flight and perched. An experi- Hawk, with four notched primaries. But the dark carpal enced birder, MR had never seen a raptor that had this bird’s conflicting patches, the dark belly-band, features: Its wing shape was like that of Swainson’s Hawk, but it had dark the white bases of the tail carpal patches and feathered tarsi, like those of Rough-legged Hawk. MR feathers, and the feathered placed digiscoped photos of this hawk on his web site <www. -

Proposals 2018-C

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-C 1 March 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae 02 10 Split Yellow Warbler (Setophaga petechia) into two species 03 25 Revise the classification and linear sequence of the Tyrannoidea (with amendment) 04 39 Split Cory's Shearwater (Calonectris diomedea) into two species 05 42 Split Puffinus boydi from Audubon’s Shearwater P. lherminieri 06 48 (a) Split extralimital Gracula indica from Hill Myna G. religiosa and (b) move G. religiosa from the main list to Appendix 1 07 51 Split Melozone occipitalis from White-eared Ground-Sparrow M. leucotis 08 61 Split White-collared Seedeater (Sporophila torqueola) into two species (with amendment) 09 72 Lump Taiga Bean-Goose Anser fabalis and Tundra Bean-Goose A. serrirostris 10 78 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 11 87 Transfer Loxigilla portoricensis and L. violacea to Melopyrrha 12 90 Split Gray Nightjar Caprimulgus indicus into three species, recognizing (a) C. jotaka and (b) C. phalaena 13 93 Split Barn Owl (Tyto alba) into three species 14 99 Split LeConte’s Thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei) into two species 15 105 Revise generic assignments of New World “grassland” sparrows 1 2018-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee pp. 87-105 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae Background: Our current linear sequence of the Accipitridae, which places all the kites at the beginning, followed by the harpy and sea eagles, accipiters and harriers, buteonines, and finally the booted eagles, follows the revised Peters classification of the group (Stresemann and Amadon 1979). -

The Systematic Position of Certain Hawks in the Genus Buteo

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VoL. 80 OCTOnER,1963 No. 4 THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF CERTAIN HAWKS IN THE GENUS BUTEO N•.v K. Jo•so• A•V I•s J. P•.•.T•.RS THE mostrecent authoritative work dealingwith the North and Middle AmericanFalconiformes states that the genusButeo "is sucha composite (that is, is so variablewithin its includedsubgenera) that any description of the genusas a wholewould be largelya matter of exceptionsin one or anothersubgenus of all the genericcharacters." In otherwords, the group "defiessubdivision" (Friedmann, 1950: 212-213), and it is apparentthat the existingsubgeneric classification of North Americanforms is largely subjective. The presentreport attempts to delineatewhat seemsto be a natural unit of five New World speciesof Buteo basedupon certaincommon fea- turesof plumage,proportions, distribution, and behavior.These species, hereafter referred to as the "woodlandbuteos," are the RoadsideHawk ( B. magnirostris) , Ridgway'sHawk ( B. ridgwayi) , Red-shoulderedHawk (B. lineatus),Broad-winged Hawk (B. platypterus),and Gray Hawk or Mexican Goshawk (B. nitidus). GEOG•Ar•IC A•I) ECOLOGIC D•ST•mUT•O• For purposesof discussion,the followingsynopsis of distributionof the woodlandbuteos is presented.Except whereotherwise noted, statements regardinggeographic range are basedon the Check-listof North American birds (A.O.U., 1957) and on the Distributionalcheck-list of the birds of Mexico, Part I (Friedmann et al., 1950). The Roadside Hawk occurs from Mexico to Argentina, with 16 races recognizedby Hellmayrand Conover(1949) and alsoby Peters(1931). Mexicanraces prefer open country, second-growth woods, and forestedge (Blake, 1953). In the provinceof Bocasdel Toro, Panama,Eisenmann (1957: 250) foundit to be an "edge"species. -

Bird Checklist for Saguaro National Park: Rincon Mountain District

he Rincon Mountain District (RMD) of Saguaro √ Common name A H S √ Common name A H S √ Common name A H S TNational Park is ecologically diverse—a quality that is DUCKS AND GEESE whiskered screech-owl U WC,F S olive-sided fycatcher R Ri,D,WC,F M refected in this bird list of over 200 species. The Rincon mallard O Ri,D Y great horned owl U Ri,D,WC,F Y greater pewee C WC,F S Mountains are part of the Madrean Archipelago of “Sky TURKEYS AND QUAIL northern pygmy-owl R WC,F Y western wood-pewee C Ri,D,WC S Islands,” where the Rocky Mountains of the U.S. meet scaled quail R D,WC Y cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl O Ri,D Y willow fycatcher O Ri M Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental. The ranges of many subtropical plant and animal species (e.g., sulphur-bel- Gambel’s quail A Ri,D,WC Y elf owl C Ri,D,WC S Hammond’s fycatcher U Ri,D,WC,F M lied fycatcher, elegant trogon) reach their northernmost Montezuma quail U WC Y burrowing owl O D M gray fycatcher U Ri,D,WC W extent here. The RMD also lies at the interface of the wild turkey U Ri,WC,F Y Mexican spotted owl R WC,F Y dusky fycatcher R Ri,D,WC,F M Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts and includes biological BITTERNS, HERONS AND EGRETS long-eared owl R Ri,D,WC,F M Pacifc-slope fycatcher U Ri,D,WC M elements from both. -

Accipitridae Species Tree

Accipitridae I: Hawks, Kites, Eagles Pearl Kite, Gampsonyx swainsonii ?Scissor-tailed Kite, Chelictinia riocourii Elaninae Black-winged Kite, Elanus caeruleus ?Black-shouldered Kite, Elanus axillaris ?Letter-winged Kite, Elanus scriptus White-tailed Kite, Elanus leucurus African Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides typus ?Madagascan Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides radiatus Gypaetinae Palm-nut Vulture, Gypohierax angolensis Egyptian Vulture, Neophron percnopterus Bearded Vulture / Lammergeier, Gypaetus barbatus Madagascan Serpent-Eagle, Eutriorchis astur Hook-billed Kite, Chondrohierax uncinatus Gray-headed Kite, Leptodon cayanensis ?White-collared Kite, Leptodon forbesi Swallow-tailed Kite, Elanoides forficatus European Honey-Buzzard, Pernis apivorus Perninae Philippine Honey-Buzzard, Pernis steerei Oriental Honey-Buzzard / Crested Honey-Buzzard, Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard, Pernis celebensis Black-breasted Buzzard, Hamirostra melanosternon Square-tailed Kite, Lophoictinia isura Long-tailed Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis longicauda Black Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis infuscatus ?Black Baza, Aviceda leuphotes ?African Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda cuculoides ?Madagascan Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda madagascariensis ?Jerdon’s Baza, Aviceda jerdoni Pacific Baza, Aviceda subcristata Red-headed Vulture, Sarcogyps calvus White-headed Vulture, Trigonoceps occipitalis Cinereous Vulture, Aegypius monachus Lappet-faced Vulture, Torgos tracheliotos Gypinae Hooded Vulture, Necrosyrtes monachus White-backed Vulture, Gyps africanus White-rumped Vulture, Gyps bengalensis Himalayan -

Raptor Banding in the Rio Grande Valley: Winter 2011-2012 by William S

Raptor Banding In The Rio Grande Valley: Winter 2011-2012 By William S. (Bill) Clark domestic mice as lures. Raptors were caught Photos by Author. either in sugar cane fields that have recently I have been banding raptors in the Rio been harvested or from perches along sides Grande Valley (RGV) since I moved here in of roads. A full set of measurements were 2002. Most of my banding activity has been taken on each raptor: wing chord, body mass, in the winter, but I have captured and banded culmen, hallux, and tail length. Photographs raptors in every month. I captured more rap- of many were taken with one wing extended tors last winter than during any previous win- from front and back. ter. Herein I will describe the raptors caught My studies. I am doing a study of the by species as to age, sex (if applicable), and molts and plumages of White-tailed Hawk. subspecies and describe some unusual ones, as They are unique among Buteos in that they well as some others caught in previous years. do not reach adult plumage for three or four I caught a total of 347 raptors from No- years, not one year as in most other Buteos. vember 12, 2011 to March 11, 2012 during One study is on the plumages of each age 21 full days and 4 partial days of active band- class as determined by the molt of the remiges ing. The totals by species, subspecies, age, and rectrices, and another study, with coau- and sex are shown in Table 1. -

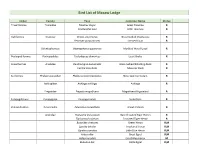

Bird List of Macaw Lodge

Bird List of Macaw Lodge Order Family Taxa Common Name Status Tinamiformes Tnamidae Tinamus major Great Tinamou R Crypturellus soul Little Tinamou R Galliformes Cracidae Ortalis cinereiceps Gray-headed Chachalaca R Penelope purpurascens Crested Guan R Odontophoridae Odontophorus gujanensis Marbled Wood-Quail R Podicipediformes Podicipedidae Tachybaptus dominicus Least Grebe R Anseriformes Anatidae Dendrocygna autumnalis Black-bellied Whistling-Duck R Cairina moschata Muscovy Duck R Suliformes Phalacrocoracidae Phalacrocorax brasilianus Neotropic Cormorant R Anhingidae Anhinga anhinga Anhinga R Fregatidae Fregata magnificens Magnificent Frigatebird R Eurypygiformes Eurypygidae Eurypyga helias Sunbittern R Pelecaniformes Pelecanidae Pelecanus occidentalis Brown Pelican R Ardeidae Tigrisoma mexicanum Bare-throated Tiger-Heron R Tigrisoma fasciatum Fasciated Tiger-Heron R Butorides virescens Green Heron R,M Egretta tricolor Tricolored Heron R,M Egretta caerulea Little Blue Heron R,M Ardea alba Great Egret R,M Ardea herodias Great Blue Heron M Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret R,M Egretta thula Snowy Egret R,M Nyctanassa violacea Yellow-crowned Night-Heron R,M Cochlearius cochlearius Boat-billed Heron R Threskiornithidae Eudocimus albus White Ibis R Mesembrinibis cayennensis Green Ibis R Platalea ajaja Roseate Sponbill R Charadriiformes Charadriidae Vanellus chilensis Southern Lapwing R Charadrius semipalmatus Semipalmated Plover M Recurvirostridae Himantopus mexicanus Black-necked Stilt R,M Scolopacidae Tringa semipalmata Willet M Tringa solitaria