Revisiting Radical Renfrew and the Anthologising of Scotland's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Executive

DATA LABEL: Public Education Executive West Lothian Civic Centre Howden South Road LIVINGSTON EH54 6FF 6 November 2014 A meeting of the Education Executive of West Lothian Council will be held within Council Chambers, West Lothian Civic Centre on Tuesday 11 November 2014 at 10:00 a.m. For Chief Executive BUSINESS Public Session 1. Apologies for Absence 2. Order of Business, including notice of urgent business 3. Declarations of Interest - Members should declare any financial and non- financial interests they have in the items of business for consideration at the meeting, identifying the relevant agenda item and the nature of their interest. 4. Minutes (a) Confirm Draft Minute of the Meeting of the Education Executive held on Tuesday 30 September 2014 (herewith). (b) Confirm Draft Minute of the Special Meeting of the Education Executive held on Tuesday 14 October 2014 (herewith). Public Items for Decision 5. Home Educated Children and Young People Policy - Report by Head of Education (Quality Assurance) (herewith) 6. School Excursion Policy - Report by Head of Schools with Education Support (herewith) - 1 - DATA LABEL: Public 7. Partnership Agreement with Education Scotland - Report by Head of Education (Quality Assurance) and Head of Schools with Education Support (herewith) 8. Consultation on Adoption of Admission Arrangements - Specialist Provision - Report by Head of Education (Quality Assurance) (herewith) ------------------------------------------------ NOTE For further information please contact Elaine Dow on 01506 281594 or email [email protected] - 2 - DATA LABEL: Public 117 MINUTE of MEETING of the EDUCATION EXECUTIVE of WEST LOTHIAN COUNCIL held within COUNCIL CHAMBERS, WEST LOTHIAN CIVIC CENTRE on 30 SEPTEMBER 2014. -

Planning Performance Framework 2017

PLANNING PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK 2017 Shore Street, Gourock (Cover photo: Brisbane Street, Greenock) 2 PLANNING PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK 2017 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 PART 1: DEFINING AND MEASURING A HIGH QUALITY PLANNING SERVICE 5 QUALITY OF OUTCOMES 6 QUALITY OF SERVICE AND ENGAGEMENT 10 GOVERNANCE 13 CULTURE OF CONTINUOUS IMPROVEMENT 14 PART 2: SUPPORTING EVIDENCE 19 PART 3: SERVICE IMPROVEMENTS 24 PART 4: NATIONAL HEADLINE INDICATORS 28 PART 5: OFFICIAL STATISTICS 32 PART 6: WORKFORCE INFORMATION 36 APPENDIX A : PERFORMANCE MARKERS 42 3 PLANNING PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK 2017 INTRODUCTION Planning Performance Frameworks were developed by Heads of Planning Scotland and first introduced by planning authorities in 2012. The framework has evolved since then, to now capture key elements of what the Scottish Government considers to be a high-performing planning service. These include: • speed of decision-making • certainty of timescales, process and advice • delivery of good quality development • project management • clear communications and open engagement • an overall ‘open for business’ attitude This Framework gives a balanced measurement of the overall quality of the planning service in Inverclyde, identifying what happened in 2016-17 as well as what is planned for 2017-18. It will form the basis on which the Scottish Government will assess planning performance against the backdrop of Inverclyde Council determining planning applications considerably faster than the Scottish average and benefitting from an up-to–date Local Development Plan and on-track replacement. Dutch Gable House, William Street, Greenock 4 PLANNING PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK 2017 PART 1: DEFINING AND MEASURING A HIGH QUALITY PLANNING SERVICE 5 PLANNING PERFORMANCE FRAMEWORK 2017 QUALITY OF OUTCOMES HILL FARM Hill Farm was initially identified as an expansion to Inverkip in the 1946 Clyde Valley Regional Plan, with planning permissions first being granted by Renfrew County Council for a “new community” in 1974. -

Tom Leonard (1944 -2018) — 'Notes Personal' in Response to His Life

Tom Leonard (1944 -2018) — ‘Notes Personal’ in Response to his Life and Work an essay by Jim Ferguson 1. How I met the human being named ‘Tom Leonard’ I was ill with epilepsy and post-traumatic stress disorder. It was early in 1986. I was living in a flat on Causeyside Street, Paisley, with my then partner. We were both in our mid-twenties and our relationship was happy and loving. We were rather bookish with quite a strong sense of Scottish and Irish working class identity and an interest in socialism, social justice. I think we both held the certainty that the world could be changed for the better in myriad ways, I know I did and I think my partner did too. You feel as if you share these basic things, a similar basic outlook, and this is probably why you want to live in a little tenement flat with one human being rather than any other. We were not career minded and our interest in money only stretched so far as having enough to live on and make ends meet. Due to my ill health I wasn’t getting out much and rarely ventured far from the flat, though I was working on ‘getting better’. In these circumstances I found myself filling my afternoons writing stories and poems. I had a little manual portable typewriter and would sit at a table and type away. I was a very poor typist which made poetry much more appealing and enjoyable because it could be done in fewer words with a lot less tipp-ex. -

West Renfrew Hills Local Landscape Area Draft

West Renfrew Hills Local Landscape Area Statement of Importance Contents 1. Introduction 2. Policy Context 3. Study Approach 4. Statement of Importance 4.1 Landscape Overview 4.2 Landscape Description 4.3 Local Landscape Area Boundary 4.4 Landscape Change 4.5 Other Designations and Interests 1. INTRODUCTION The West Renfrew Hills lie within the Clyde Muirshiel Regional Park and stretch from Inverkip and Wemyss Bay in the west to the edge of Loch Thom in the east and adjoin the North Ayrshire Special Landscape Area to the south. Patterns of hillside and coastal landscapes combine with the varied patterns of vegetation to help define the character of the rural areas and provide a functional setting for the urban areas of Inverclyde. 2. POLICY CONTEXT Scotland’s landscapes are recognised as a major asset, contributing to national, regional and local identities, adding to the qualities of many people’s lives and providing attractive settings which help promote social and economic development. The European Landscape Convention (ELC) highlights the importance of an ‘all landscapes’ approach to landscaping and encourages more attention to their care and planning. This provides a framework for work on Scotland's landscapes based on a set of five principles: people, from all cultures and communities, lie at the heart of efforts for landscape, as we all share an interest in, and responsibility for, its well-being; the landscape is important everywhere, not just in special places and whether beautiful or degraded; landscapes will continue to evolve in response to our needs, but this change needs to be managed; better awareness and understanding of our landscapes and the benefits they provide is required; and an inclusive, integrated and forward-looking approach to managing the landscapes we have inherited, and in shaping new ones, is required. -

West Lothian LOCATION 02

Gateway Up to 84 acres for commercial and industrial development J4 / M8 / West Lothian LOCATION 02 A811 M90 Kirkcaldy STIRLING To Aberdeen To North and Inverness A92 A905 Aberdeen M9 Dunfermline Dundee M80 Grangemouth Rosyth A9 A904 A891 A993 A90 A803 A803 A904 Falkirk M9 Dumbarton Linlithgow A90 Newcastle A81 Cumbernauld A8 A82 Kirkintilloch Leeds Bathgate A8 A80 Lothian Gateway M8 EDINBURGH M898 GLASGOW A701 A90 Manchester Renfrew M80 M73 Livingston A71 A720 M8 Airdrie M8 M8 Coatbridge Birmingham M74 Extension A70 A702 Paisley M74/M6 London A737 A724 A749 M77 A73 A725 Motherwell A71 A701 Newton To Prestwick Airport Mearns Hamilton A726 To South and Carlisle A723 PRIME LOCATION KEY TRAVEL TIMES Sat Nav Postcode: Lothian Gateway Miles KMS Drive Time Lothian Gateway occupies a strategic location within Central Scotland being accessed from EH 47 Junctions 3A and 4 of the M8 motorway. The site is approximately 17 miles west of Edinburgh city to: (Approx. Mins) centre and 32 miles east of Glasgow city centre. The M8 motorway provides direct links to all of Scotland's motorway networks leading north and south. Edinburgh and Glasgow International airports are also within easy reach. Scotland's largest cargo port, at Grangemouth, is approximately Edinburgh Airport 14 23 21 12 miles to the north Glasgow 26 42 32 Edinburgh 26 42 35 More specifically, Lothian Gateway has the benefit of two access points. Access from the east side is Glasgow Airport 34 56 40 through Whitehill Industrial Estate, Bathgate's main industrial location. From the west access is taken Port of Glasgow 46 75 53 through J4 M8 development directly from Junction 4A. -

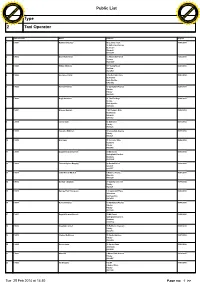

Public List Type 2 Taxi Operator

Ch F-X ang PD e Public List w w m w Click to buy NOW! o . .c tr e Type ac ar ker-softw 2 Taxi Operator Reference No. Name Address Expires 1 TX001 Raymond Stanley 4E Lennox Court 31/08/2014 14 Sutherland Avenue Bearsden Glasgow G61 3JW 2 TX002 David Robertson 37 Alexandra Parade 31/05/2014 Dunoon PA23 8AF 3 TX003 William Mottram 117 Sandy Road 30/09/2014 Renfrew PA4 0BX 4 TX004 Ian James Fairlie 4 Castle Farm Close 30/06/2014 Stewarton East Ayrshire KA3 3DU 5 TX005 Kenneth Barnes 10 Springfield Avenue 30/04/2014 Ralston Paisley PA1 3LD 6 TX006 Hugh Anderson 11 The Fieldings 31/08/2014 Dunlop East Ayrshire KA3 4AU 7 TX007 Graeme Hannah 1 St. Ronan's Drive 30/09/2014 Shawlands Glasgow G41 3SJ 8 TX008 Jason Clark 34 Golf Drive 30/11/2014 Paisley PA1 3LA 9 TX009 Cameron McIntosh 12 Lounsdale Avenue 30/09/2014 Paisley PA2 9LT 10 TX010 Eric Egan 11 Fereneze Drive 30/06/2014 Glenburn Paisley PA2 8NS 11 TX011 Dugald Stewart Russell 30 Mill Court 30/06/2014 Springbank Gardens Dunblane FK15 9JZ 12 TX012 Thomas Spiers Baggley 26 Rockall Drive 31/12/2014 Simshill G44 5ET 13 TX013 John Woods Mitchell 5 Wallace Avenue 30/09/2014 Elderslie PA5 9LN 14 TX014 Gordon Chapman 20 Stanely Crescent 30/06/2014 Paisley PA2 9LF 15 TX015 George Paul Thompson 3 Craigdonald Place 30/06/2014 Johnstone Renfrewshire PA5 8EH 16 TX016 Kenneth Barnes 10 Springfield Avenue 31/05/2015 Ralston Paisley PA1 3LD 17 TX017 Dugald Stewart Russell 30 Mill Court 31/05/2015 Springbank Gardens Dunblane FK15 9JZ 18 TX018 Skyedale Limited 16 Redhurst Crescent 31/05/2014 Paisley PA2 8PX 19 TX019 Charles McKinnon 75 Castle Gardens 31/07/2014 Paisley PA2 9RA 20 TX020 Steven Irw in 39 Speirs Road 30/06/2014 Johnstone PA5 8HX 21 TX021 Allan Hill 2 Manor Park Avenue 31/10/2015 Paisley PA2 9BF 22 TX022 Iris Dougans Flat 0/1 31/03/2015 2 Saucel Place Paisley PA1 1UE Tue 25 Feb 2014 at 14:30 Page no: 1 >> Ch F-X ang PD e Reference No. -

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register This guide is to help you fill in your application form for Highland Housing Register. It also gives you some information about social rented housing in Highland, as well as where to find out more information if you need it. This form is available in other formats such as audio tape, CD, Braille, and in large print. It can also be made available in other languages. Contents PAGE 1. About Highland Housing Register .........................................................................................................................................1 2. About Highland House Exchange ..........................................................................................................................................2 3. Contacting the Housing Option Team .................................................................................................................................2 4. About other social, affordable and supported housing providers in Highland .......................................................2 5. Important Information about Welfare Reform and your housing application ..............................................3 6. Proof - what and why • Proof of identity ...............................................................................................................................4 • Pregnancy ...........................................................................................................................................5 • Residential access to children -

Scottish Nationalism

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Summer 2012 Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination Brian Duncan James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Duncan, Brian, "Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination" (2012). Masters Theses. 192. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scottish Nationalism: The Symbols of Scottish Distinctiveness and the 700 Year Continuum of the Scots’ Desire for Self Determination Brian Duncan A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History August 2012 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….…….iii Chapter 1, Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 2, Theoretical Discussion of Nationalism………………………………………11 Chapter 3, Early Examples of Scottish Nationalism……………………………………..22 Chapter 4, Post-Medieval Examples of Scottish Nationalism…………………………...44 Chapter 5, Scottish Nationalism Masked Under Economic Prosperity and British Nationalism…...………………………………………………….………….…………...68 Chapter 6, Conclusion……………………………………………………………………81 ii Abstract With the modern events concerning nationalism in Scotland, it is worth asking how Scottish nationalism was formed. Many proponents of the leading Modernist theory of nationalism would suggest that nationalism could not have existed before the late eighteenth century, or without the rise of modern phenomena like industrialization and globalization. -

Scottish Poetry 1974-1976 Alexander Scott

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 13 | Issue 1 Article 19 1978 Scottish Poetry 1974-1976 Alexander Scott Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Scott, Alexander (1978) "Scottish Poetry 1974-1976," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 13: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol13/iss1/19 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alexander Scott Scottish Poetry 1974-1976 For poetry in English, the major event of the period, in 1974, was the publication by Secker and Warburg, London, of the Com plete Poems of Andrew Young (1885-1971), arranged and intro duced by Leonard Clark. Although Young had lived in England since the end of the First World War, and had so identified himself with that country as to exchange his Presbyterian min istry for the Anglican priesthood in 1939, his links with Scotland where he was born (in Elgin) and educated (in Edin burg) were never broken, and he retained "the habit of mind that created Scottish philosophy, obsessed with problems of perception, with interaction between the 'I' and the 'Thou' and the 'I' and the 'It,."l Often, too, that "it" was derived from his loving observation of the Scottish landscape, to which he never tired of returning. Scarcely aware of any of this, Mr. Clark's introduction places Young in the English (or Anglo-American) tradition, in "the field company of John Clare, Robert Frost, Thomas Hardy, Edward Thomas and Edmund Blunden ••• Tennyson and Browning may have been greater influences." Such a comment overlooks one of the most distinctive qualities of Young's nature poetry, the metaphysical wit that has affinities with those seven teenth-century poets whose cast of mind was inevitably moulded by their religion. -

Prevention Key Risks in Renfrewshire

Scottish Fire and Rescue Service David Proctor Area Manager Local Senior Officer for Renfrewshire ERRI Management Structure East Renfrewshire, Renfrewshire and Inverclyde Area Map Area Based Resources • Fire Control- - Handle 50% of all calls in Scotland, Mobilise resources for all of the West of Scotland • Special appliances- Greenock (ARP), Paisley (ARP), Johnstone (ALP) & Renfrew (PODS) • Fire Enforcement teams- Greenock & Paisley • Community Action Team located at The Safety Centre Renfrewshire Stations • Station Manager Eddie Finnieston in charge of: S01 Johnstone 1 Rescue Appliance, 1 RDS Rescue Appliance, 1 RDS Aerial Ladder Platform (ALP) S02 Paisley 1 Aerial Rescue Platform (ARP) & 1 Rescue Appliance S03 Renfrew 1 Rescue Appliance and Specialist resource Pods: Welfare Pod, Mass Decontamination Pod, Environmental Protection Unit, Foam Pod, Flood and Environmental Response Unit Our Priorities- Draft Local Fire Plan • Domestic Fire Safety • Unintentional Harm and Injury • Deliberate Fire Setting • Non-Domestic Fire Safety • Unwanted Fire Alarm Signals • Operational Resilience and Preparedness Renfrewshire Performance Stats 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 Fire fatalities 0 1 0 1 Fire Casualties 60 32 39 38 Accidental dwelling fires 223 221 207 179 Non domestic fires 76 84 88 78 Deliberate fires 604 543 627 764 UFAS 1374 1350 1414 1463 Community Action Team • Based at The Safety Centre at Paisley Fire Station • Team consists of: – Local Area Liaison Officer (LALO) – 2 Community Fire Fighters – 2 Community Advocates Community Action -

Nicholas Brooke Phd Thesis

THE DOGS THAT DIDN'T BARK: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND NATIONALISM IN SCOTLAND, WALES AND ENGLAND Nicholas Brooke A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2016 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/8079 This item is protected by original copyright The Dogs That Didn't Bark: Political Violence and Nationalism in Scotland, Wales and England Nicholas Brooke This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 30th June 2015 1 Abstract The literature on terrorism and political violence covers in depth the reasons why some national minorities, such as the Irish, Basques and Tamils, have adopted violent methods as a means of achieving their political goals, but the study of why similar groups (such as the Scots and Welsh) remained non-violent, has been largely neglected. In isolation it is difficult to adequately assess the key variables behind why something did not happen, but when compared to a similar violent case, this form of academic exercise can be greatly beneficial. This thesis demonstrates what we can learn from studying ‘negative cases’ - nationalist movements that abstain from political violence - particularly with regards to how the state should respond to minimise the likelihood of violent activity, as well as the interplay of societal factors in the initiation of violent revolt. This is achieved by considering the cases of Wales, England and Scotland, the latter of which recently underwent a referendum on independence from the United Kingdom (accomplished without the use of political violence) and comparing them with the national movement in Ireland, looking at both violent and non-violent manifestations of nationalism in both territories. -

Phonetic Study of Dialect Writing in Tom Leonard's Six Glasgow Poems

DEPARTAMENT DE FILOLOGIA ANGLESA I DE GERMANÍSTICA Phonetic Study of Dialect Writing in Tom Leonard’s Six Glasgow Poems Treball de Fi de Grau/ BA Dissertation Author: Helena Barbara Style Muñoz Supervisor: Maria-Josep Solé i Sabaté Grau d’Estudis Anglesos June 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor Prof. Maria-Josep Solé for considering my original proposal and for helping me develop it into this work. I really appreciate all her guidance, advice, dedication and encouragement. I would also like to thank my teacher Prof. Núria Gavaldà, for being the one who sparked my interest in the field of Phonetics, an interest I am sure I will never lose. I am grateful for my parents’ unconditional love and support, and for teaching me one of the most valuable lessons I have ever learnt, which is to enjoy learning. I am also grateful for my classmates who have now become my friends, and especially Paola for being so supportive and always believing in me. I would like to dedicate this paper to all my teachers here at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona whose teachings have not only come together in this work, but will live within me forever. Table of contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..1 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..2 2. Scotland and Glasgow: the linguistic situation……………………………………………3 2.1 Scotland………………………………………………………………………………..3 2.2 Glasgow………………………………………………………………………………..6 3. Dialect in literature………………………………………………………………………...8 4. Features analysed and procedure…………………………………………………………12 5. Analysis…………………………………………………………………………………..13 5.1. Segmental features: A. Consonants………...………………………………………………………………………14 1. L-vocalization……………………………………………………………………...14 2. Rhoticity…………………………………………………………………………...15 3. H-dropping…………………………………………………………………………16 B. Vowels………...…………………………………………………………………………..17 4.