The Tapestry Cartoons and New Social Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Recorrido Didáctico Por El Madrid Neoclásico

Biblioteca Digital Madrid, un libro abierto RECORRIDO DIDÁCTICO POR EL MADRID NEOCLÁSICO POR ANA CHARLE SANZ Bloque II. Madrid Histórico Número H 31 RECORRIDO DIDÁCTICO POR EL MADRID NEOCLÁSICO POR ANA CHARLE SANZ Contenido OBJETIVOS ....................................................................................................... 4 CUADRO CRONOLÓGICO ................................................................................ 5 EL ARTE NEOCLÁSICO .................................................................................... 8 Contextualización y características generales: ............................................... 8 ARQUITECTURA NEOCLÁSICA EN ESPAÑA ................................................ 14 Ventura Rodríguez (1717-1785).................................................................... 15 Francesco Sabatini (1722-1797) ................................................................... 17 Juan de Villanueva (1739-1811) ................................................................... 18 Otros arquitectos: .......................................................................................... 20 CONTENIDOS ................................................................................................. 23 Conceptos ..................................................................................................... 23 Procedimientos ............................................................................................. 23 Actitudes ...................................................................................................... -

The Business Organisation of the Bourbon Factories

The Business Organization of the Bourbon Factories: Mastercraftsmen, Crafts, and Families in the Capodimonte Porcelain Works and the Royal Factory at San Leucio Silvana Musella Guida Without exaggerating what was known as the “heroic age” of the reign of Charles of Bourbon of which José Joaquim de Montealegre was the undisputed doyen, and without considering the controversial developments of manufacturing in Campania, I should like to look again at manufacturing under the Bourbons and to offer a new point of view. Not only evaluating its development in terms of the products themselves, I will consider the company's organization and production strategies, points that are often overlooked, but which alone can account for any innovative capacity and the willingness of the new government to produce broader-ranging results.1 The two case studies presented here—the porcelain factory at Capodimonte (1740-1759) and the textile factory in San Leucio (1789-1860)—though from different time periods and promoted by different governments, should be considered sequentially precisely because of their ability to impose systemic innovations.2 The arrival of the new sovereign in the company of José Joaquin de Montealegre, led to an activism which would have a lasting effect.3 The former was au fait with economic policy strategy and the driving force of a great period of economic modernization, and his repercussions on the political, diplomatic and commercial levels provide 1 For Montealegre, cf. Raffaele Ajello, “La Parabola settecentesca,” in Il Settecento, edited by Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli (Naples, 1994), 7-79. For a synthesis on Bourbon factories, cf. Angela Carola Perrotti, “Le reali manifatture borboniche,” in Storia del Mezzogiorno (Naples, 1991), 649- 695. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016" (2016). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 73. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1. SPRING, 2016 TSA Board Member and Newsletter Editor Wendy Weiss behind the scenes at the UCB Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, durring the TSA Board meeting in March, 2016 Spring 2016 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (Membership & Communications Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

Goya's Lost Snuffbox

MA.OCT.Ceron_Cooke.pg.proof.corrs:Layout 1 15/09/2010 10:35 Page 675 Goya’s lost snuffbox by MERCEDES CERÓN ON 17TH JUNE 1793, the following advertisement appeared in the ‘Lost property’ section of the Diario de Madrid: Lost in the afternoon of the 5th of this month, a rectangular gold box, engraved all over [with decoration], and with six paintings whose author is David Theniers [sic]. It went miss- ing between the Convent of the Incarnation and the Prado: anyone finding it should hand it in to Don Francisco de Goya, painter to His Majesty the King, who lives in the Calle del Desengaño, on the left-hand side coming from Fuencarral, No. 1, flat 2, where they will be generously rewarded.1 What works by Teniers were lost by Goya on the way to the Prado? The ambiguity of the advertisement renders the iden - tification of the paintings problematic. Despite the confusing phrasing, emphasis seems to be placed on the box, rather than on its contents. It seems therefore likely that the six pictures were not inside the case, but rather attached to the sides and to the lid as part of its decoration. Genre scenes loosely derived from 24. Box decorated with enamels of peasant interiors in the manner of David Teniers, by Jean Ducrollay. Paris, 1759–60. Gold and enamel, 4.1 by 8.1 by 5.9 cm. Teniers’s works were an ornamental motif favoured by Parisian (Victoria and Albert Museum, London). goldsmiths such as Eloy Brichard (1756–62) and Jean Ducrollay (c.1708–after 1776), and they often embellished their gold and coronation of Charles IV and María Luisa as King and Queen of enamel snuffboxes with such scenes. -

Dare We Forget?

AJR Information Volume XLIX No. 4 April 1994 £3 (to non-members) Don't miss . Reflections on the Hidden Children New title competition p3 Dare we forget? The Survivor's ta.\e pi2 welve days into the countdown from the but to speak out in order to lighten their burden and A Republic Second Seder Night to the beginning of Shavuot to help themselves and each other to come to terms there is a day of quite distinctive sadness which, with their traumatic legacy. without T in the opinion of one Jewish theologian, 'the thinkers Republicans p/6 A book has just been published which records in and the rabbis do not yet know how to observe'. deeply moving fashion the details of a number of these In 1991 it was observed by sixteen hundred Jewish 'secret survivors of the Holocaust'. In it, the 'few men and women meeting in New York for what was speak for the many' of their shared past, of their False analogy possibly one of the most significant experiences of ordeal in the hiding places of their war-time years, their adult lives. They came together to remember that their liberation from immediate danger and its which they would rather have forgotten and to aftermath and of their need to find a way to being fter the Hebron examine that which, after five decades, they were healed at last and so to be released from the prison mosque unable to forget: their childhood innocence destroyed without bars of their mental anguish and despair. A for no good reason other than that they were Jews. -

Texto Completo

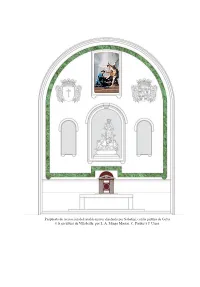

Propuesta de recreación del retablo mayor diseñado por Sabatini, con la pintura de Goya y la escultura de Villabrille, por L. A. Mingo Macías, C. Pardos y J. Urrea BRAC, 54, 2019, pp. 72-85, ISNN: 1132-078 LOS CAPUCHINOS DEL PRADO: PEREDA, VILLABRILLE, SABATINI Y GOYA Jesús Urrea Fernández Académico Resumen: La austeridad de la orden capuchina no estuvo reñida en su madrileño convento de San Antonio del Prado con la presencia en su templo de obras de arte de sobresaliente interés. Los sucesivos altares que tuvo su presbiterio contaron con la intervención de artistas tan destacados como Antonio Pereda, Juan Alonso Villabrille y Ron, Francesco Sabatini o Francisco de Goya. En el trabajo se aportan novedades y precisiones sobre todos ellos y se propone la recreación del último retablo mayor que tuvo la iglesia. Palabras clave: Orden capuchina. Madrid. Convento de San Antonio. Arquitectura, escultura y pintura de los siglos XVII y XVIII. Antonio Pereda. Juan Alonso Villabrille y Ron. Francesco Sabatini. Francisco de Goya. THE CAPUCHINS OF THE PRADO. PEREDA, VILLABRILLE, SABATINI AND GOYA Abstract: The austerity of the Capuchin order it is not reflected in the convent of San Antonio del Prado, Madrid, where the presence in its temple of outstanding pieces of art make it unique. The successive altars that its presbytery had had were the result of the intervention of such prominent artists as Antonio Pereda, Juan Alonso Villabrille y Ron, Francesco Sabatini or Francisco de Goya. The following article provides a highly detailed new approach of all of the works of the aforementioned artists. -

Diplomatic Realignment Between the War of Rosellon and the War of Oranges in the Days of Gomes Freire De Andrade

War compasses: diplomatic realignment between the war of Rosellon and the war of Oranges in the days of Gomes Freire de Andrade Ainoa Chinchilla Galarzo Throughout the 18th century, both Spain and Portugal decided to join the two great powers of the moment: France and England, respectively, in order to maintain their overseas empires. The defense of these territories depended on the threat of the dominant maritime power of the moment: England; therefore, these two States were forced to choose one of the two options. As we already know, the alignments of France with Spain and, on the other hand, of England with Portugal, would lead them to be in [1] opposing positions throughout the eighteenth century . In the first place, the decision of the Spanish government was due to their capacity to face the maritime strength of the English, which was not enough. Spain needed France´s support to fight against the hegemony which the English intended at sea, since the French power was becoming the rival to take into account. Therefore, the Spanish government decided to join its steps to [2] those of France with the signing of three Family Pacts . On the other hand, Portugal, as a gateway to the Atlantic Ocean, needed British aid to keep its overseas territories, since its interests and reality were wholly linked to the control of the sea. Hence the alliance with the English nation, was ratified in the treaty of Methuen of 1703. These alignments allowed each of them to have the help of their ally in case it was needed, while leaving room for the own politics of each State. -

Francisco De Goya Y Lucientes

FRANCISCO DE GOYA Y LUCIENTES Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes is regarded as the most important Spanish artist of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries Francisco was born in Fuendetodos, Spain on March 30, 1746. He took his first art lessons from his father, who was a master gilder. Francisco also learned etching from friendly local monks. He became an apprentice at age 14 to a village painter and realized that he wanted to become an artist. However, the art academy rejected him in 1763 and 1766, which greatly disappointed the young man. Goya didn't give up on his dream of becoming a painter, though, and traveled to Italy to study. He learned how to paint in the bold Rococo style and even won second prize in a painting contest in Rome. Goya triumphantly went back to Spain in 1771 and began painting frescoes in the local cathedral. He also studied with an artist named Francisco Bayeu and later married Bayeu's sister, Josefa. His marriage helped him get a job creating designs for the royal tapestry factory in Madrid from 1775 until 1792. He designed 42 tapestries that showed scenes from everyday life, and he developed new techniques that helped weavers do their craft with precision. Tapestry design was fun, but Goya still wanted to be a full-time painter. Goya's big break came in 1783. One of the king's friends asked Goya to paint his portrait, which turned out well. Soon, Goya had other patrons. He became popular for his amazing portraits. Many of them had an element of mystery to them. -

Filippo Juvara, Diseña Un Enorme Cuadrilátero De 500 Metros De Lado

AULADADE PALACIO REAL DE MADRID -Arte y Poder- Javier Blanco Planelles A lo largo de la historia de la civilización occidental, el palacio principesco ha sido un poderoso símbolo político y social. Además de servir como residencia del monarca y como centro de gobierno, el palacio constituía la manifestación más expresiva de las riquezas y la gloria obtenida a través del dominio de los hombres y las tierras. Por su propia naturaleza , se convirtió en exponente de los valores de la clase rectora; en él se reunían, ordenaban y expresaban de forma visual una serie de ideas. Brown J., y Ellioth J. H. Un palacio para el Rey, Madrid 1981. Primavera: ARANJUEZ Itinerario Real Otoño y comienzo invierno: EL ESCORIAL Verano: VALSAÍN, LA GRANJA Invierno: EL PARDO El prestigio de la Francia barroca se impone e imita como es el sistema de las lujosas residencias periféricas, de las que el Alcázar de Madrid es el auténtico centro 1700 NUEVO SIGLO La llegada de los Borbones a España conllevará: NUEVA DINASTIA • La introducción de nuevos valores cortesanos y políticos. • Recuperación social, política y comercial • Relativo bienestar, incremento nivel de vida • Aumento de la población • Progresiva regeneración económica • Aumento de la burguesía y la clase media • Disminución del clero y de la nobleza (estamentos no productivos). • Mejoras en la agricultura y el comercio con América Felipe V (1700-1746) • Reforzar el Estado • Crear de un marco económico fuerte. • Frenar a la iglesia prepotente • Reforzar y estrechar los vínculos entre el arte español y el arte franco- italiano. • Potenciar la investigación y la experiencia artística española. -

Historic Organs of Spain

Historic Organs of Spain Historic organs OF May 13-25, 2013 13 DAYS Spain with J. Michael Barone www.americanpublicmedia.org www.pipedreams.org National broadcasts of Pipedreams are made possible with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, by a gift from Mr. and Mrs. Wesley C. Dudley, by a grant from the MAHADH Fund of HRK Foundation, by the contributions of listeners to American Public Media stations, and through the support of the Associated Pipe Organ Builders of America, APOBA, representing designers and creators of fine instruments heard throughout the country, on the Web at www.apoba.com, and toll-free at 800-473-5270. See and hear Pipedreams on the Internet 24-7 at www.pipedreams.org. A complete booklet pdf with the tour itinerary can be accessed online at www.pipedreams.org/tour Table of Contents Welcome Letter Page 2 Historical Background Page 3-14 Alphabetical List of Organ Builders Page 15-18 Organ Observations: Some Useful Terms Page 19-20 Discography Page 21-25 Bios of Hosts and Organists Page 26-30 Tour Itinerary Page 31-35 Organ Sites Page 36-103 Rooming List Page 104 Traveler Bios Page 105-108 Hotel List Page 109 Map Inside Back Cover Thanks to the following people for their valuable assistance in creating this tour: Natalie Grenzing, Laia Espuña and Isabel Lavandeira in Barcelona; Sam Kjellberg of American Public Media; Valerie Bartl, Janelle Ekstrom, Cynthia Jorgenson, Janet Tollund, and Tom Witt of Accolades International Tours for the Arts. We also gratefully acknowledge the following sources for this booklet: Asociación Antonio de Cabezón, Asociación Fray Joseph de Echevarria de Amigos del Organo de Gipuzkoa. -

Bernardo De Lriarte. of the Palm Cenus Lriartea

156 PRINCIPES [Vor. 29 Principes,29(4), I985, pp. I56-159 Bernardo de lriarte. of the Palm Cenus lriartea R. A. DrFnIpps Departnent of Botany, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20560 In the last decades of the eighteenth Charles IV who received 41,900 pesosin century, the Spanish colonies in the New donationsfrom the fortunate peopleon his "suggested World were organized into gigantic Empire-wide list of contribu- o'viceroyal- administrative regions termed tors." Ruiz and Pavon followed an under- ties," the government of which was super- standableprocedure, glorifying new plant vised by the Council of the Indies in discoveries by naming several in com- Madrid with ultimate responsibility vested memoration of the sponsorsand well-wish- in the King. These massive domains ers of their expedition. Thus, in the Prod- included" from north to south, the vice- rotnus are found newly described, for royalty of New Spain (present-day south- example, the genera Carludoaica western United States, Mexico, and Cen- (Cyclanthaceae,compounded in reference tral America north of Panama); the to patrons King Charles IV and Queen viceroyalty of New Granada (today's Louisa); Godoya (Ochnaceae,for Manuel Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Pan- de Godoy, benefactor of Madrid's Royal ama); and the viceroyalty of Peru. Botanical Garden, King's Minister and Expecting the discovery of new dimen- Queen'sparamour); and, on page 149 the sions in mineral and plant wealth, includ- genus lriartea for Don Bernardo de ing mercuryo cinnamon and quinine at Iriarte, promoter of the noble arts and various times, the kings sent expeditions sciences,especially botany, and councillor to New Granadain 1750 (directed by Jos6 on matters of the Indies.