T47 I Vow to Thee My Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States, Great Britain, the First World

FROM ASSOCIATES TO ANTAGONISTS: THE UNITED STATES, GREAT BRITAIN, THE FIRST WORLD WAR, AND THE ORIGINS OF WAR PLAN RED, 1914-1919 Mark C. Gleason, B.S. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major-Professor Robert Citino, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Gleason, Mark C. From Associates to Antagonists: The United States, Great Britain, the First World War, and the Origins of WAR PLAN RED, 1914-1919. Master of Arts (History), May 2012, 178 pp., bibliography, 144 titles. American military plans for a war with the British Empire, first discussed in 1919, have received varied treatment since their declassification. The most common theme among historians in their appraisals of WAR PLAN RED is that of an oddity. Lack of a detailed study of Anglo- American relations in the immediate post-First World War years makes a right understanding of the difficult relationship between the United States and Britain after the War problematic. As a result of divergent aims and policies, the United States and Great Britain did not find the diplomatic and social unity so many on both sides of the Atlantic aspired to during and immediately after the First World War. Instead, United States’ civil and military organizations came to see the British Empire as a fierce and potentially dangerous rival, worthy of suspicion, and planned accordingly. Less than a year after the end of the War, internal debates and notes discussed and circulated between the most influential members of the United States Government, coalesced around a premise that became the rationale for WAR PLAN RED. -

Harmsworth, Alfred Charles William, Viscount Northcliffe | International

Version 1.0 | Last updated 21 October 2016 Harmsworth, Alfred Charles William, Viscount Northcliffe By Adrian Bingham Harmsworth, Alfred Charles William (1st Viscount Northcliffe, Lord Northcliffe) Newspaper Owner Born 15 July 1865 in Chapelizod, Ireland Died 14 August 1922 in London, Great Britain Lord Northcliffe was the owner of the influential London newspapers the Daily Mail and The Times, and a powerful critic of the Asquith administration’s prosecution of the war. In the final years of the war he took up official positions as head of the war mission to the United States, and Director of Propaganda in Enemy Countries. Table of Contents 1 Introduction 2 Predicting the War 3 Wartime Interventions 3.1 On the Attack 3.2 Official positions 4 Peace-making and Legacy Notes Selected Bibliography Citation Introduction Alfred Harmsworth (1865-1922), ennobled in 1905 as Lord Northcliffe, was the most influential and controversial British newspaper proprietor of the modern era. He founded the Daily Mail (1896) and the Daily Mirror (1903), the two most successful daily newspapers of the early 20th century. He had strong political views and repeatedly used his newspapers to intervene in public life. During the First World War he was at the height of his powers, and created numerous political storms with his scathing criticisms of the military and civilian administration, and his plotting against Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith (1852- 1928). Northcliffe was born near Dublin in 1865, and moved into journalism at an early age, with the spectacular success of theD aily Mail and the Daily Mirror ensuring his fame and fortune. -

Official America's Reaction to the 1916 Rising

The Wilson administration and the 1916 rising Professor Bernadette Whelan Department of History University of Limerick Chapter in Ruan O’Donnell (ed.), The impact of the 1916 Rising: Among the Nations (Dublin, 2008) Woodrow Wilson’s interest in the Irish question was shaped by many forces; his Ulster-Scots lineage, his political science background, his admiration for British Prime Minister William Gladstone’s abilities and policies including that of home rule for Ireland. In his pre-presidential and presidential years, Wilson favoured a constitutional solution to the Irish question but neither did he expect to have to deal with foreign affairs during his tenure. This article will examine firstly, Woodrow Wilson’s reaction to the radicalization of Irish nationalism with the outbreak of the rising in April 1916, secondly, how the State Department and its representatives in Ireland dealt with the outbreak on the ground and finally, it will examine the consequences of the rising for Wilson’s presidency in 1916. On the eve of the rising, world war one was in its second year as was Wilson’s neutrality policy. In this decision he had the support of the majority of nationalist Irish-Americans who were not members of Irish-American political organisations but were loyal to the Democratic Party.1 Until the outbreak of the war, the chief Irish-American political organizations, Clan na Gael and the United Irish League of America, had been declining in size but in August 1914 Clan na Gael with Joseph McGarrity as a member of its executive committee, shared the Irish Republican Brotherhood’s (IRB) view that ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity’ and it acted to realize the IRB’s plans for a rising in Ireland against British rule. -

Arthur Balfour and the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1894-1923

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository A Matter of Imperial Defence: Arthur Balfour and the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, 1894-1923 Takeshi Sugawara A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History November 2014 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” 1 Abstract This thesis investigates Arthur Balfour’s policy towards Japan and the Anglo-Japanese alliance from 1894 to 1923. Although Balfour was involved in the Anglo-Japanese alliance from its signing to termination, no comprehensive analysis of his role in the alliance has been carried out. Utilising unpublished materials and academic books, this thesis reveals that Balfour’s policy on the Anglo-Japanese alliance revolved around two vital principles, namely imperial defence and Anglo-American cooperation. From the viewpoint of imperial defence, Balfour emphasised the defence of India and Australasia more than that of China. He opposed the signing of the Anglo-Japanese alliance of 1902 because it was not useful in the defence of India. The Russo-Japanese War raised the concern of Indian security. Changing his lukewarm attitude, Balfour took the initiative in extending the alliance into India to employ Japanese troops for the defence of India. -

The Relations of Woodrow Wilson with the British Government 1914 - 1917

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1938 The Relations of Woodrow Wilson with the British Government 1914 - 1917 Elizabeth M. Shanley Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Shanley, Elizabeth M., "The Relations of Woodrow Wilson with the British Government 1914 - 1917" (1938). Master's Theses. 469. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/469 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1938 Elizabeth M. Shanley THE RELATIONS OF WOODROW WILSON WITH THE BRITISH GOVERNMENT 1914 - 1917 Elizabeth M. Shanley Loyola University TABLE OF CON'lENTS page I. The Trad1t1onal Fore1gn Pollcy of the Unlted states 1 II. The Problems ot Neutrallty 9 III. The Controversy over Neutral 31 Rlghts IV. Attempts at Medlatlon 63 V. The End of Isolatlon 81 .' Chapter 1 The Traditional Foreign Policy of the United states The memorable message which President Wilson addressed to the Extraordinary Session of Congress on April 2, 1917, advis lng a Declaration of War against the Imperial Government of Germany, stands as a landmark in the hlstory of the foreign policy of the United states. His action, arising from his conviction that the honor of the United states could be main tained only by actively espousing the cause of the Allies, marks a reversal Of the time-honored and cherished attltude of non-intervention which through the years had become an in- tegral part Of oUr national llfe. -

Bbm:978-1-349-18546-7/1.Pdf

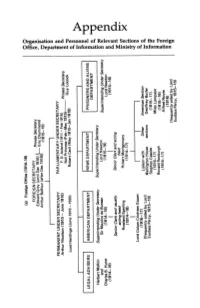

(a) Foreign Office (1914-18) 00 FOREIGN SECRETARY Private Secretary Edward Grey (until Dec 1916) }-Eric Drummond ..~i ... Arthur Balfour (after Dec 1916) (1915-19) oil tD a. I "tS 0 I l ~ =:s PERMANENT UNDER SECRETARY PARLIAMENTARY UNDER SECRETARY Arthur Nicolson (1910- June 1916) F. D. Acland (1911- Feb 1915) Private Secretary i=tD c. Neil Primrose (Feb-May 1915)-- Cecil (May 1915-Jan 1919) Guy Locock a~ Lord Hardinge (June 1916 -1920) Robert 0 tD ....-o ;! I I I I S.s > LEGAL ADVISERS 'AMERICAN DEPARTMENT' 'NEWS DEPARTMENT' PRISONERS AND ALIENS t!. ~ I I DEPARTMENT a ~ a. ~ Herbert Malkin Superintending Under Secretary Superintending Under Secretary Newton g.:= and Sir Maurice de BUnsen Lord Superintending Under Secretary tD (1915-16) =:s ro Charles B. Hurst (1914-18) Lord Newton ~ -tD (1914-18) I I (1915-16) =:s < ~ Senior Clerk and usually Senior Clerk and acting c.= a:: ... 0.. acting head head ... Cll ,.... Sperling Hubert Montgomery Rowland ...=:s I')tD (1914-18) (1914-17) X I I ---~ ~§ Lord Colum Crichton Stuart I 0 fll (1916-17) Liaison with Other American Section .... 0 (frequently aided by Lord Wellington House sections Geoffrey Butler =:f .... Eustace Percy, 1915-16) Stephen Gaselee (1915-17) a'Ef (1916-171 Miles Lampson ... tD Ronald Roxburgh (1915-16) 2 :r (1916-17) Alfred Noyes a.; (1916) 0 ... (frequently aided by Lord =:s~ Eustace Percy, 1915-16) (b) Department of Information (Feb 1917-Jan 1918) SUPERINTENDING CABINET MINISTER Lloyd George (Feb-Sep 1917) Edward Carson (Sep 1917-Jan 1918) I DIRECTOR John Buchan-Private Secretary: 1 Stair Gillion I l I l AND LIBRARY [INTELLIGENCE STAF~ ADMINISTRATION-ALLIED I~RT I ~u~~;-~~TAFFJ AND NEUTRAL PROPAGANDA Assistant Director Financial Assistant Director Deputy Director Charles Masterman Comptroller Major-General Lord Hubert Montgomery ~-·--I Edward Gleichen I -, I -1 Books Distribution Pictorial Art t~- Pamphlets Publications ATFO ABROAD Newspapers Exhibitions USA USA Ronald Roxburgh Geoffrey Butler Far East and Moslem H. -

Phi Beta Kappa and the British Commission Reprint from the Phi Beta Kappa Key

•^-."^..e^- cc. hr^-UX_t-<>^> V J \ PHI BETA KAPPA AND THE BRITISH COMMISSION REPRINT FROM THE PHI BETA KAPPA KEY PHI BETA KAPPA'S GREATEST DAY (From THE KEY, May 1917, p, 187,) iVIay 17, 1917, will be memorable in Phi Beta Kappa annals be cause of the distinguished function that took place in Washington, D, C, at which the British Ambassador, Sir Cecil Spring-Rice, the Right Honorable Arthur James Balfour, and eleven members of the British Commission, graduates of Cambridge and Oxford, were granted Honorary membership in Phi Beta Kappa, Dr. Hol- lis Godfrey for the Senate presented the candidates, President Lyon G, Tyler of the College of William and Mary welcomed the members; Robert M. Hughes, President of the Alpha of Virginia, repeated the ancient "Oath of Fidelity," gave the grip and pre sented the keys; and President Grosvenor spoke on the signifi cance of the Phi Beta Kappa in the realm of patriotism as well as in letters and education, Mr, Balfour responded in an eloquent address, concluding with these words. "On behalf of my friends and myself I beg to thank you for the greatest honor which you could possibly confer, and which we could possibly receive," Twelve Senators were present, and also the French Ambassador, M. Jusserand, an Honorary member of the Alpha of Massachu setts, All appeared in academic costume. The entire body was later entertained at luncheon by Dr, and Mrs. Godfrey, We have but room for this brief account of this significant oc casion in this number of THE KEY, A full account will appear in the October number, with portraits of the members of the Com- Copyright, Clinedinst Studio, Washington, D. -

Michael Patrick Cullinane THEODORE ROOSEVELT in THE

Downloaded from https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537781415000559 The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 15 (2016), 80–101 doi:10.1017/S1537781415000559 https://www.cambridge.org/core Michael Patrick Cullinane THEODORE ROOSEVELT IN THE EYES OF THE ALLIES . IP address: As Woodrow Wilson traveled across the Atlantic to negotiate the peace after World War I, Theo- 170.106.35.234 dore Roosevelt died in Long Island. His passing launched a wave of commemoration in the United States that did not go unrivaled in Europe. Favorable tributes inundated the European press and coursed through the rhetoric of political speeches. This article examines the sentiment of Allied nations toward Roosevelt and argues that his posthumous image came to symbolize American in- , on tervention in the war and, subsequently, the reservations with the Treaty of Versailles, both endear- 26 Sep 2021 at 19:46:02 ing positions to the Allies that fueled tributes. Historians have long depicted Woodrow Wilson’s arrival in Europe as the most celebrated reception of an American visitor, but Roosevelt’s death and memory shared equal pomp in 1919 and endured long after Wilson departed. Observing this epochal moment in world history from the unique perspective of Roosevelt’s passing extends the already intricate view of transnational relations. , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at Concerning brave Captains Our age hath made known For all men to honor, One standeth alone, Of whom, o’er both oceans Both Peoples may say: “Our realm is diminished With Great-Heart away.”—Rudyard Kipling1 Theodore Roosevelt’s death in the early hours of January 6, 1919, surprised the world. -

Cecil Spring Rice ?R

POEMS CECIL SPRING RICE ?R /fsa (i[atmU itnittecBttg Siibtatg 3tt)ata, £3eni Qorb BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF HENRY W. SAGE 1891 Library Cornell University PR6037.P97A171920 Poems. 382 ... 3 1924 013 225 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013225382 POEMS BY CECIL ARTHUR SPRING RICE i/Us^fii iti.ic<>Ur t-: 'uitua^^aM,s^ 'l^^ece/J>yiMu^ S^t/Um^ K^^cce< v/^^6: POEMS BY CECIL ARTHUR SPRING -RICE G.C.M.G., P.C. LATE BRITISH AMBASSADOR TO THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA I WITH PORTRAIT LONGMANS, GREEN AND QO. 39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON FOURTH AVENUE St 30TH STREET, NEW YORK BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAS 1920 {\¥\nio CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE vii PERSIAN SONNETS I IN MEMORIAM, A. C. M. L 1 24 OTHER POEMS 170 [ V ] PREFACE It is to be hoped that a Memoir of Cecil Arthur Spring Rice will some day be written. Meanwhile a short outline of his career will be useful as an introduction to these poems, which I have been asked by Lady Spring Rice to edit. The Rices were, presumably, originally of Welsh descent, sons of Rhys, but those of this line appear in Ireland, in County Kerry, in the reign of Henry VIII. Sir Stephen Rice (1637-17x5) was Chief Baron of Exchequer in 1686, and a vigorous supporter of the Catholic and National cause under James II. -

Economic Drives A

Essay from “Australia’s Foreign Wars: Origins, Costs, Future?!” http://www.anu.edu.au/emeritus/members/pages/ian_buckley/ This Essay (illustrated) also available on The British Empire at: http://www.britishempire.co.uk/article/australiaswars5.htm 5. World War One: Economic Drives A. Economic motives behind Australia’s support in WWI 1 (a) 1916: In desperation, - British Cabinet’s hopes for negotiated peace… (b) ..but Kitchener’s assurances Lure them on to 'Victory’…. (c) ...and renewed hopes of crushing German competition (d) The Somme and… (e)...the urgent call for conscription. (f) Lloyd George undermines Wilson’s peace proposals… (g) ..but President Wilson persists (h) Finally, the US opts for war. (i) A second Australian Referendum on Conscription – also fails! (j) Russia sues for peace… (k) ..and Allies close to collapse (l) …but Wilson set on victory - but with a just peace … (m) ...while Hughes, like others, intent on ‘spoils of war’ B. General Reflections on the War's Economic Origins 14 C. Sources 15 ………………………. A. Economic motives behind Australia’s support in WWI With such tragically disastrous results all round from WWI (e.g. 5A (a, d) & 6) it’s appropriate to examine the motivations for the war from Australian as well as British perspectives. What was it all about? Our politicians’ rhetorical ‘justification’ for the war was, as always, couched in idealistic (though truly inadequate) terms, such as ‘this is a war for Justice and Liberty, - to save the Empire from German militarism’, etc., all supposedly laudable arguments (see 5A(e) below). That is, if you don’t look at the realities behind the jargon, for there was never any German military threat to Britain’s home islands or overseas Empire territories – Australia included. -

The Maritime Way in Munitions: the Entente and Supply in the First World War

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 14, ISSUES 3 & 4, 2012 Studies The Maritime Way in Munitions: The Entente and Supply in the First World War Keith Neilson The First World War marks a watershed in political, social and military terms. In a political sense, it brought an end to the long nineteenth century and caused the collapse of four empires, ushered in Bolshevism and set the stage for both fascism and Nazism. It also upset the existing social order, bringing about a revolution in the relations between ruled and rulers. All of this occurred due to what has been termed the first ‘total war’, a conflict that involved all aspects of society at an unprecedented level. Such remarks are commonplace (and to some extent debatable).1 However, what is undeniable is that the First World War was fought on an industrial scale, and that munitions of war were consumed at an unprecedented and formerly impossible rate. At 1 For the problems with the term ‘total war’, see Roger Chickering, ‘Total War: The Use and Abuse of a Concept’, in Manfred F. Boemke, Roger Chickering and Stig Förster, eds: pp. 13-28, Anticipating Total War. The German and American Experiences, 1871-1914, Washington, DC and Cambridge: German Historical Institute/Cambridge University Press, 1999. ©Centre of Military and Strategic Studies, 2012 ISSN : 1488-559X JOURNAL OF MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES the simplest level, this was possible because of the industrial revolution. However, such a statement, while true, is to simplify and homogenize what occurred. A deeper-level analysis demonstrates that it was not the industrial revolution as such, but the surrounding changes that accompanied it, that made possible the actual conflict as it was fought and the consumption of articles of war at the level that occurred. -

Some Aspects of British Propaganda During the World War, 1914-1918

SOME ASPECTS OF BRITISH PROPAGANDA DURING THE WORLD WAR, 1914-1918 By Sister Mary Cleopha Peil, O.P., B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin 1 9 4 2 'L (~F\/:..r)!J/\···i ~ ",1 ''''.... , '1- ;V'iP.. h\.JiJt. ~ 1 :,'. l V":f-~6rrY 9065 78 CON TEN T S ---000--- CHAPTER PAGE Preface.. ••• ••• • ••••••••• iii I Introduction • • • • • • • •• ••••• 1 II England's Organization of Propaganda •••••• 8 III The Crewe House Committee. • • • • • • • • • • • 20 IV British Propaganda in Germany. • • • • • • • • • 27 V "Hands Across the Sea" •••• • •• ••••• 39 VI America's Decision for War. • • • • • • • • •• 59 Bibliography • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• • 63 PREFACE This thesis on, Some Aspects £! British Propaganda During the World~, 19l4-~, is an attempt to show how British propaganda was one of the causes for America's entrance into the World War. It would be impossible to express appreciation to all who made it possible for me to write this dissertation. But in a general way, I wish to thank those who were un tiring in their encouragement and who lightened, ~y their willing assistance, the weight of my work in order to give me more time and opportunity to prepare this paper. Among the libraries which I have used, special men tion is due to the John Crerar Library of Chicago, the Chicago Public Library, which gave me access to the book entitled, ~ Secrets £! Crewe House, to which I have de voted an entire chapter in my thesis. speCial acknowledg ment is also due to the Librarian of Stanford University, california, who graciously loaned me material on propaganda.