On the Swedish Polska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sweden As a Crossroads: Some Remarks Concerning Swedish Folk

studying culture in context Sweden as a crossroads: some remarks concerning Swedish folk dancing Mats Nilsson Excerpted from: Driving the Bow Fiddle and Dance Studies from around the North Atlantic 2 Edited by Ian Russell and Mary Anne Alburger First published in 2008 by The Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, MacRobert Building, King’s College, Aberdeen, AB24 5UA ISBN 0-9545682-5-7 About the author: Mats Nilsson works as a senior lecturer in folklore and ethnochoreology at the Department of Ethnology, Gothenburg University, Sweden. His main interest is couple dancing, especially in Scandinavia. The title of his1998 PhD dissertation, ‘Dance – Continuity in Change: Dances and Dancing in Gothenburg 1930–1990’, gives a clue to his theoretical orientation. Copyright © 2008 the Elphinstone Institute and the contributors While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in the Elphinstone Institute, copyright in individual contributions remains with the contributors. The moral rights of the contributors to be identified as the authors of their work have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. 8 Sweden as a crossroads: some remarks concerning Swedish folk dancing MATS NILSSON his article is an overview of folk dancing in Sweden. The context is mainly the Torganised Swedish folk-dance movement, which can be divided into at least three subcultures. Each of these folk dance subcultural contexts can be said to have links to different historical periods in Europe and Scandinavia. -

Swedish Folk Music

Ronström Owe 1998: Swedish folk music. Unpublished. Swedish folk music Originally written for Encyclopaedia of world music. By Owe Ronström 1. Concepts, terminology. In Sweden, the term " folkmusik " (folk music) usually refers to orally transmitted music of the rural classes in "the old peasant society", as the Swedish expression goes. " Populärmusik " ("popular music") usually refers to "modern" music created foremost for a city audience. As a result of the interchange between these two emerged what may be defined as a "city folklore", which around 1920 was coined "gammeldans " ("old time dance music"). During the last few decades the term " folklig musik " ("folkish music") has become used as an umbrella term for folk music, gammeldans and some other forms of popular music. In the 1990s "ethnic music", and "world music" have been introduced, most often for modernised forms of non-Swedish folk and popular music. 2. Construction of a national Swedish folk music. Swedish folk music is a composite of a large number of heterogeneous styles and genres, accumulated throughout the centuries. In retrospect, however, these diverse traditions, genres, forms and styles, may seem as a more or less homogenous mass, especially in comparison to today's musical diversity. But to a large extent this homogeneity is a result of powerful ideological filtering processes, by which the heterogeneity of the musical traditions of the rural classes has become seriously reduced. The homogenising of Swedish folk music started already in the late 1800th century, with the introduction of national-romantic ideas from German and French intellectuals, such as the notion of a "folk", with a specifically Swedish cultural tradition. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 2, 2014, at 8:00 Friday, October 3, 2014, at 1:30 Saturday, October 4, 2014, at 8:30 Riccardo Muti Conductor Christopher Martin Trumpet Panufnik Concerto in modo antico (In one movement) CHRISTOPHER MARTIN First Chicago Symphony Orchestra performances Performed in honor of the centennial of Panufnik’s birth Stravinsky Suite from The Firebird Introduction and Dance of the Firebird Dance of the Princesses Infernal Dance of King Kashchei Berceuse— Finale INTERMISSION Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 3 in D Major, Op. 29 (Polish) Introduction and Allegro—Moderato assai (Tempo marcia funebre) Alla tedesca: Allegro moderato e semplice Andante elegiaco Scherzo: Allegro vivo Finale: Allegro con fuoco (Tempo di polacca) The performance of Panufnik’s Concerto in modo antico is generously supported by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute as part of the Polska Music program. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Andrzej Panufnik Born September 24, 1914, Warsaw, Poland. Died October 27, 1991, London, England. Concerto in modo antico This music grew out of opus 1.” After graduation from the conserva- Andrzej Panufnik’s tory in 1936, Panufnik continued his studies in response to the rebirth of Vienna—he was eager to hear the works of the Warsaw, his birthplace, Second Viennese School there, but found to his which had been devas- dismay that not one work by Schoenberg, Berg, tated during the uprising or Webern was played during his first year in at the end of the Second the city—and then in Paris and London. -

Nordic Roots Dance Kari Tauring - 2014 "Dance Is a Feature of Every Significant Occasion and Event Crucial to Tribal Existence As Part of Ritual

Nordic Roots Dance Kari Tauring - 2014 "Dance is a feature of every significant occasion and event crucial to tribal existence as part of ritual. The first thing to emphasize is that early dance exists as a ritual element. It does not stand alone as a separate activity or profession." Joan Cass, Dancing Through History, 1993 In 1989, I began to study runes, the ancient Germanic/Nordic alphabet system. I noticed that many rune symbols in the 24 Elder Futhark (100 ACE) letters can be made with one body alone or one body and a staff and some require two persons to create. I played with the combination of these things within the context of Martial Arts. In the Younger futhark (later Iron Age), these runes were either eliminated or changed to allow one body to create 16 as a full alphabet. In 2008 I was introduced to Hafskjold Stav (Norwegian Family Tradition), a Martial Arts based on these 16 Younger Futhark shapes, sounds and meanings. In 2006 I began to study Scandinavian dance whose concepts of stav, svikt, tyngde and kraft underpinned my work with rune in Martial Arts. In 2011/2012 I undertook a study with the aid of a Legacy and Heritage grant to find out how runes are created with the body/bodies in Norwegian folk dances along with Telemark tradition bearer, Carol Sersland. Through this collaboration I realized that some runes require a "birds eye view" of a group of dances to see how they express themselves. In my personal quest to find the most ancient dances within my Norwegian heritage, I made a visit to the RFF Center (Rådet for folkemusikk og folkedans) at the University in Trondheim (2011) meeting with head of the dance department Egil Bakka and Siri Mæland, and professional dancer and choreographer, Mads Bøhle. -

TOCN0004DIGIBKLT.Pdf

NORTHERN DANCES: FOLK MUSIC FROM SCANDINAVIA AND ESTONIA Gunnar Idenstam You are now entering our world of epic folk music from around the Baltic Sea, played on a large church organ and the nyckelharpa, the keyed Swedish fiddle, in a recording made in tribute to the new organ in the Domkirke (Cathedral) in Kristiansand in Norway. The organ was constructed in 2013 by the German company Klais, which has created an impressive and colourful instrument with a large palette of different sounds, from the most delicate and poetic to the most majestic and festive – a palette that adds space, character, volume and atmosphere to the original folk tunes. The nyckelharpa, a traditional folk instrument, has its origins in the sixteenth century, and its fragile, Baroque-like sound is happily embraced by the delicate solo stops – for example, the ‘woodwind’, or the bells, of the organ – or it can be carried, like an eagle flying over a majestic landscape, with deep forests and high mountains, by a powerful northern wind. The realm of folk dance is a fascinating soundscape of irregular pulse, ostinato- like melodic figures and improvised sections. The melodic and rhythmic variations they show are equally rich, both in the musical tradition itself and in the traditions of the hundreds of different types of dances that make it up. We have chosen folk tunes that are, in a more profound sense, majestic, epic, sacred, elegant, wild, delightful or meditative. The arrangements are not written down, but are more or less improvised, according to these characters. Gunnar Idenstam/Erik Rydvall 1 Northern Dances This is music created in the moment, introducing the mighty bells of the organ. -

The Christmas Revels Program Book

The 48th annual production With David Coffin Merja Soria The Kalevala Chorus The Solstånd Children Infrared listening devices and The Briljant String Band large print programs are available The Northern Lights Dancers at the Sanders Theatre Box Office. The Midnight Sun Mummers The Pinewoods Morris Men for Please visit our lobby table Karin’s Sisters Revels recordings, books, cards Cambridge Symphonic Brass Ensemble and more. Our new CD, The Gifts of Odin: A Nordic Christmas Revels, features much of the music from Lynda A. Johnson, Production Manager this year’s show! Jeremy Barnett, Set Design Jeff Adelberg, Lighting Design Heidi Hermiller, Costume Design Bill Winn, Sound Design Ari Herzig, Projection Design Thanks to our generous Corporate Partners With support and Media Sponsors: from: TM www.cambridgetrust.com CONTENTS Introduction Please join us in “All Sings” on pages 5, 10, 12, 14 and 16! Welcome to the 48th annual Christmas Revels! Sven is a dreamer and his father’s patience is wearing THE PROGRAM page 4 thin. It is Christmas and the big house is bustling with preparations for a party that will bring together ministers PARTICIPANTS page 17 and dignitaries from all the Scandinavian countries to meet the new Ambassador of Finland. The seasonal festivities do little to reduce Sven’s moodiness that FEATURED ARTISTS page 22 seems to be tied to the loss of his favorite uncle. Change comes in the guise of three unusual Christmas presents. They usher Sven into an alternative universe populated by witches, A NOTE ON THE KALEVALA snakes and superheroes, where he is reunited with his late uncle Finland Finds Its National Identity page 35 in a series of life-changing adventures. -

Kardemimmit and Finnish Folk Music

Arts Midwest Folkefest Study Guide Kardemimmit from FINLAND About the Artists Kardemimmit is made up of four women from Finland who sing and play the Finnish national instrument, the kantele. All four members of the group grew up in the city of Espoo, and formed the band at the musical institute there in 1999. Since then, they have released four albums and performed around the world. Their unique, modern folk sound mixes vocal harmonies with the bell-like tones of the kantele. Members Maija Pokela Jutta Rahmel Anna Wegelius Leeni Wegelius Samuli Volanto (sound engineer) The members of Kardemimmit. From left to right: Finnish Music Anna, Jutta, Maija, and Leeni. Photos by Jimmy Träskelin. The songs that Kardemmimit play come from several different Finnish musical traditions. Runolaulu (poem song) is an ancient form of Finnish singing. Runo songs have a simple rhythm, with four emphasized syllables per line, and use only five notes of a scale. The lines of the songs start with the same letter sound, but the ends do not rhyme. As with ancient poetry, runo songs often focus on epic tales of heroes, magicians, and quests for adventure. Rekilaulu (sleigh song) is a more modern form of Finnish song. The structure of each reki song is the same—it has four lines in each stanza, and the second and fourth lines rhyme with each other. Besides being fun to listen to, some of Kardemimmit’s songs might make you want to dance—that’s because they’re dance songs! Polska, schottische, and hambo are all traditional Scandinavian dances, often performed at social events like weddings. -

Ncsnlapril 2014.Pages

Promoting Scandinavian Folk Music and Dance April 2014 Scandia Camp Mendocino Rikard Skjelkvåle is a 3rd generation fiddler and farmer in Skjåk. He has learnt to play in the June 14-21, 2014 ! old style in Lom and Skjåk. He will play for the Dance & Music of Skjåk, Gudbransdal, dances from Skjåk, Gudbrandsdal. Norway Stig and Helén Eriksson have both received Ingrid Maurstad Tuko & Nils Slapgård their big silver medals for polska dancing and (dance) they won the Hälsinge Hambo contest in 1993. Rikard Skjelkvåle (music) Both are musicians in the folk music band ! Klintetten. Dance & Music of Östergötland, Dalarna Mikael and David Eriksson have been (& more) Sweden inspired by their parents Stig & Helén and have Stig & Helén Eriksson and won Hambo & gammaldans contests, achieved Mikael & David Eriksson (dance) their big silver medals in polska dance, and Jon Holmén (music) dance Swedish popular dance including what ! we call swing. Singing Ingrid Maurstad Tuko Jon Holmén has played the violin most of his Hardingfele & Beginning Fiddle life. He grew up and has his musical roots in Laura Ellestad the area around Lake Siljan. He is an Nyckelharpa Bart Brashers experienced teacher and dance-musician with a Allspel Peter Michaelsen particular interest in how the dance and music Scandianavian Dance Fundamentals relate to each other. Jon is currently employed Roo Lester & Harry Khamis ! at Folkmusikens Hus in Rättvik and at Falun Conservatory of Music. Ingrid Maurstad Tuko learned to dance at (Continued on page 2) home, her grandfather and uncles were ! especially inspiring. She will share some ! Newsletter Inside: Norwegian songs and perhaps even a song Southern California Skandia Festival 3 dance with us. -

2016 NFF Brochure-March

Nordic Fiddles & Feet Music & Dance of Norway & Sweden Ogontz Camp, New Hampshire Sunday, June 26 – Sunday, July 3, 2016 From Norway: Knut Arne Jacobsen and Brit B. Totland – Dances and Songs from Valdres From Sweden: Tommy and Ewa Englund – Selected dances from Dalarna, Jämtland, Medelpad, & Hälsingland Stefhan Ohlström – Dance Fiddler Sunniva Abelli – Nyckelharpa, Songs from Västerbotten Caroline Eriksson – Swedish Fiddle From the United States: Roo Lester and Larry Harding - Scandinavian Dance Basics Bruce Sagan - Gammaldans band, Nyckelharpa Loretta Kelley - Hardanger Fiddle Andrea Larson – Beginning Fiddle Experience a magical week of music and dance in the beautiful White Mountains! Choose from daily classes in dancing, fiddle, nyckelharpa, Hardanger fiddle, and singing with world-class instructors for all levels. Enrich your experience with cultural programs, concerts, and craft sessions. Relax by the lake or enjoy an afternoon canoeing, swimming, or hiking and then round off the day at the nightly dance party or jamming with friends and staff. Families Welcome! -- Children under 5 free Information Dance classes are designed for all levels of dancers. Basics with other parents for playgroup and other options. class introduces basic dance practices while teaching body mechanics and skills helpful for all levels of dancers. PayPal: Please contact Theresa for information on this Swedish and Norwegian classes feature traditional option at [email protected]. regional dances. Special additional classes may review dances taught in previous years or enrich the offerings. You Payment deadline dates: Full payment must be received by don’t need to attend camp with a dance partner. We change May 15 for the discounted rate. -

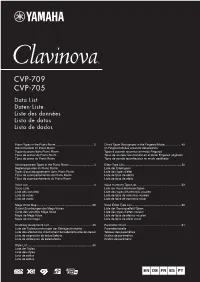

CVP-709/CVP-705 Data List

CVP-709 CVP-705 Data List Daten-Liste Liste des données Lista de datos Lista de dados Piano Types in the Piano Room............................................... 2 Chord Types Recognized in the Fingered Mode.................... 49 Klaviermodelle im Piano Room Im Fingered-Modus erkannte Akkordarten Types de piano dans Piano Room Types d’accords reconnus en mode Fingered Tipos de pianos de Piano Room Tipos de acordes reconocidos en el modo Fingered (digitado) Tipos de piano do Piano Room Tipos de acorde reconhecidos no modo dedilhado Accompaniment Types in the Piano Room .............................. 3 Effect Type List....................................................................... 50 Begleitungsarten im Piano Room Liste der Effekttypen Types d’accompagnements dans Piano Room Liste des types d’effet Tipos de acompañamientos de Piano Room Lista de tipos de efecto Tipos de acompanhamento do Piano Room Lista de tipos de efeito Voice List ................................................................................. 4 Vocal Harmony Type List ....................................................... 59 Voice-Liste Liste der Vocal-Harmony-Typen Liste des sonorités Liste des types d'harmonies vocales Lista de voces Lista de tipos de armonías vocales Lista de vozes Lista de tipos de harmonia vocal Mega Voice Map.................................................................... 30 Vocal Effect Type List............................................................. 60 Sound-Zuordnungen der Mega Voices Liste der Gesangseffekt-Typen Carte -

Philatelic & Postal Bookplates

5.4 PHILATELIC AND POSTAL BOOKPLATES by BRIAN J. BIRCH © Brian J. Birch Lieu dit au Guinot, Route de St. Barthélemy 47350 Montignac Toupinerie, France 21st February 2018 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE BOUND VOLUME Although this document is only intended to exist in electronic form, I find it very convenient to have a hard copy to hand. It is easier to refer to a book than wait the five or ten minutes it takes to start up and close down a computer, just to obtain a single reference or check a fact. Books also give you the big picture of the document as a whole rather than the small-screen glimpses we have all got used to. Accordingly, I printed and bound a copy of this document in January 2005, which I have called the First edition, for convenience. Henceforth, I will bind a copy each January, provided the document has increased in size by at least ten percent during the year. At the same time, I will send an update to the web files on www.fipliterature.org, where the electronic version of this document is hosted. Since printing and binding is quite an expensive undertaking, I donated the obsolete volumes to important philatelic libraries round the world. By the middle of 2012, in line with my other documents, I simplified the set-up and turned off the remove widows and orphans feature. This resulted in a reduction in length of 15 pages. Reducing the amount of white space is an ongoing process in an effort to minimise the page count whilst not compromising usability. -

The Case of Swedish Folk Music

Tradition as a Spatiotemporal Process – The Case of Swedish Folk Music Franz-Benjamin Mocnik Institute of Geography, Heidelberg University Im Neuenheimer Feld 348 Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract Space and time both play a major role in the evolution of traditions. While it is known that processes at different scales guide the evolution of culture, it is not yet clear which structural factors promote the emergence and persistence of traditions. This paper argues that the principle of least effort is among the factors that foster traditions, but the principle needs to be accompanied by other local processes. The theoretical discussion is supplemented by an agent-based simulation, which illustrates some of these factors and allows to study their interaction. Keywords: tradition; spatio-temporal process; agent-based simulation; folk music; Sweden; principle of least effort 1 Introduction that “[w]ithout tradition there can be no historical continuity, be- cause it is tradition which forms a link between the individual Tradition in music is based on a simple principle: musicians stages of this continuity. However, a general theory of tradition pass on their tunes to new generations, who pick up the tunes is not yet available.” by listening and mimicking. This process often leads to a con- The process of tradition happens at different scales. The indi- tinuity of the repertoire and style of how to play the tunes, often vidual musician being part of a tradition clearly has an impact even without the involved people being fully aware of the pro- on these musicians who he or she is in contact with.