Thesis Paul Meijer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 1 Kanchipuram 1 Kanchipuram 1 Angambakkam 2 Ariaperumbakkam 3 Arpakkam 4 Asoor 5 Avalur 6 Ayyengarkulam 7 Damal 8 Elayanarvelur 9 Kalakattoor 10 Kalur 11 Kambarajapuram 12 Karuppadithattadai 13 Kavanthandalam 14 Keelambi 15 Kilar 16 Keelkadirpur 17 Keelperamanallur 18 Kolivakkam 19 Konerikuppam 20 Kuram 21 Magaral 22 Melkadirpur 23 Melottivakkam 24 Musaravakkam 25 Muthavedu 26 Muttavakkam 27 Narapakkam 28 Nathapettai 29 Olakkolapattu 30 Orikkai 31 Perumbakkam 32 Punjarasanthangal 33 Putheri 34 Sirukaveripakkam 35 Sirunaiperugal 36 Thammanur 37 Thenambakkam 38 Thimmasamudram 39 Thilruparuthikundram 40 Thirupukuzhi List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 41 Valathottam 42 Vippedu 43 Vishar 2 Walajabad 1 Agaram 2 Alapakkam 3 Ariyambakkam 4 Athivakkam 5 Attuputhur 6 Aymicheri 7 Ayyampettai 8 Devariyambakkam 9 Ekanampettai 10 Enadur 11 Govindavadi 12 Illuppapattu 13 Injambakkam 14 Kaliyanoor 15 Karai 16 Karur 17 Kattavakkam 18 Keelottivakkam 19 Kithiripettai 20 Kottavakkam 21 Kunnavakkam 22 Kuthirambakkam 23 Marutham 24 Muthyalpettai 25 Nathanallur 26 Nayakkenpettai 27 Nayakkenkuppam 28 Olaiyur 29 Paduneli 30 Palaiyaseevaram 31 Paranthur 32 Podavur 33 Poosivakkam 34 Pullalur 35 Puliyambakkam 36 Purisai List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 37 -

Thiruvallur District

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR 2017 TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT tmt.E.sundaravalli, I.A.S., DISTRICT COLLECTOR TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT TAMIL NADU 2 COLLECTORATE, TIRUVALLUR 3 tiruvallur district 4 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT - 2017 INDEX Sl. DETAILS No PAGE NO. 1 List of abbreviations present in the plan 5-6 2 Introduction 7-13 3 District Profile 14-21 4 Disaster Management Goals (2017-2030) 22-28 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability analysis with sample maps & link to 5 29-68 all vulnerable maps 6 Institutional Machanism 69-74 7 Preparedness 75-78 Prevention & Mitigation Plan (2015-2030) 8 (What Major & Minor Disaster will be addressed through mitigation 79-108 measures) Response Plan - Including Incident Response System (Covering 9 109-112 Rescue, Evacuation and Relief) 10 Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 113-124 11 Mainstreaming of Disaster Management in Developmental Plans 125-147 12 Community & other Stakeholder participation 148-156 Linkages / Co-oridnation with other agencies for Disaster 13 157-165 Management 14 Budget and Other Financial allocation - Outlays of major schemes 166-169 15 Monitoring and Evaluation 170-198 Risk Communications Strategies (Telecommunication /VHF/ Media 16 199 / CDRRP etc.,) Important contact Numbers and provision for link to detailed 17 200-267 information 18 Dos and Don’ts during all possible Hazards including Heat Wave 268-278 19 Important G.Os 279-320 20 Linkages with IDRN 321 21 Specific issues on various Vulnerable Groups have been addressed 322-324 22 Mock Drill Schedules 325-336 -

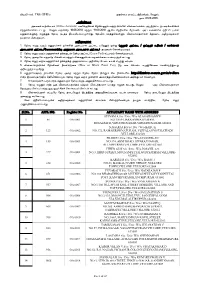

Sl.No. APPL NO. Register No. APPLICANT NAME WITH

tpLtp vz;/ 7166 -2018-v Kjd;ik khtl;l ePjpkd;wk;. ntYhh;. ehs; 01/08/2018 mwptpf;if mytyf cjtpahsh; (Office Assistant) gzpfSf;fhd fPH;f;fhqk; kDjhuh;fspd; tpz;zg;g';fs; mLj;jfl;l eltof;iff;fhf Vw;Wf;bfhs;sg;gl;lJ/ nkYk; tUfpd;w 18/08/2018 kw;Wk; 19/08/2018 Mfpa njjpfspy; fPH;f;fz;l ml;ltizapy; Fwpg;gpl;Ls;s kDjhuh;fSf;F vGj;Jj; njh;t[ elj;j jpl;lkplg;gl;Ls;sJ/ njh;tpy; fye;Jbfhs;Sk; tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs; fPH;fz;l tHpKiwfis jtwhky; gpd;gw;wt[k;/ tHpKiwfs; 1/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fspd; milahs ml;il VnjDk; xd;W (Mjhu; ml;il - Xl;Leu; cupkk; - thf;fhsu; milahs ml;il-ntiytha;g;g[ mYtyf milahs ml;il) jtwhky; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 2/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSld; njh;t[ ml;il(Exam Pad) fl;lhak; bfhz;Ltut[k;/ 3/ njh;t[ miwapy; ve;jtpj kpd;dpay; kw;Wk; kpd;dDtpay; rhjd’;fis gad;gLj;jf; TlhJ/ 4/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; kDjhuh;fs; j’;fSf;F mDg;gg;gl;l mwptpg;g[ rPl;il cld; vLj;J tut[k;/ 5/ tpz;zg;gjhuh;fs;; njh;tpid ePyk;-fUik (Blue or Black Point Pen) epw ik bfhz;l vGJnfhiy gad;gLj;JkhW mwpt[Wj;jg;gLfpwJ/ 6/ kDjhuh;fSf;F j’;fspd; njh;t[ miw kw;Wk; njh;t[ neuk; ,d;Dk; rpy jpd’;fspy; http://districts.ecourts.gov.in/vellore vd;w ,izajsj;jpy; bjhptpf;fg;gLk;/ njh;t[ vGj tUk; Kd;dnu midj;J tptu’;fisa[k; mwpe;J tu ntz;Lk;/ 7/ fhyjhkjkhf tUk; ve;j kDjhuUk; njh;t[ vGj mDkjpf;fg;glkhl;lhJ/ 8/ njh;t[ vGJk; ve;j xU tpz;zg;gjhuUk; kw;wth; tpilj;jhis ghh;j;J vGjf; TlhJ. -

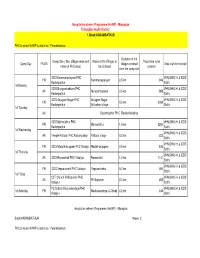

Camp Day FN/AN Camp Site ( Site, Village Name and Name of PHC Area)

Hospital on wheels Programme (HoWP) - Microplan Thiruvallur Health District 1.Block:KADAMBATHUR PHC to which HoWP is attached : Perambakkam Distance of the Camp Site ( Site, Village name and Name of the Villages to Population to be Camp Day FN/AN villages covered Area staff to involved name of PHC area) be Covered covered from the camp site ICDS Kamavarpalayam PHC VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS FN Kammavarpalyam 0.5 km 946 Kadampathur Staffs 1st Monday ICDS Nungambakkam PHC VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS AN Nungambakkam 0.5 km 988 Kadampathur Staffs ICDS Anjugam Nagar PHC Anjugam Nagar, VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS FN 0.5 km 2360 Kadampathur Adikathur village Staffs 1st Tuesday AN Kadambathur PHC Review Meeting ICDS Mellnalathur PHC VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS FN Mellnalathur 1.0 km 3264 Kadampathur Staffs 1st Wednesday VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS AN Temple Pattarai PHC Kadampathur Pattarai village 0.3 km 532 Staffs VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS FN ICDS Madathukuppam PHC Vidaiyur Madathukuppam 0.5 km 510 Staffs 1st Thursday VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS AN ICDS Raman koil PHC Vidaiyur Raman koil 1.0 km 1141 Staffs VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS FN ICDS Veppanchetti PHC Vidaiyur Veppanchettai 0.2 km 494 Staffs 1st Friday CST Church Phillispuram PHC VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS AN Phillispuram 0.2 km 455 Vidaiyur Staffs PU School Madurakandigai PHC VHN,SHN, HI & ICDS 1st Saturday FN Madurakandigai & Chenji 0.2 km 345 Vidaiyur Staffs Hospital on wheels Programme (HoWP) - Microplan Block:KADAMBATHUR Week: 2 PHC to which HoWP is attached : Perambakkam Distance of the Camp Site ( Site, Village name and Name of the Villages to Population -

Satyagraha in Democracy: Opportunities and Pitfalls

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 4, No. 7(1); May 2014 Satyagraha in Democracy: Opportunities and Pitfalls Dr. Janmit Singh Assistant Professor Department of Political Science Sewa Devi S. D. College India Abstract Satyagraha was considered as morally rightful mean to resist unjust laws in totalitarian regimes. But there is a perspective which advocates granting scope to affirmative action by individuals and groups in democratic regimes. This may provide a channel to people to articulate their political resentment and insist for improvement where political class failed to represent their aspirations. But counterargument remains that any reform must usher from the constitutional structures and any attempt to circumscribe them would prove counterproductive as it would undermine the working of democratic structures. The analysis of various such movements in general and of Anna Hazare led movement in particular reveals that such movements act as means for the empowerment of people if continued to maintain their non-partisan nature. However, any attempt on their part to act as alternative to existing political class defeats not only their own cause but proves to be disastrous for democratic regimes. Keywords: Satyagraha, Democracy, Civil Society Movements, Constitutional, Lokpal Democracy has often been represented as panacea for all sufferings of civil society. The assumption is that system rests on choosing the representatives of the people who reflect the aspirations of society and execute them. Since constitutional and peaceful means are rule of game therefore democracy mitigates multiple cleavages existent in society. However, democracy despite all its virtues did not escape criticism. Political theorists Aristotle and Tocqueville had their doubts (Cunningham, 2005) which with the passage of time have been validated. -

The Institute of Road Transport Driver Training Wing, Gummidipundi

THE INSTITUTE OF ROAD TRANSPORT DRIVER TRAINING WING, GUMMIDIPUNDI LIST OF TRAINEES COMPLETED THE HVDT COURSE Roll.No:17SKGU2210 Thiru.BARATH KUMAR E S/o. Thiru.ELANCHEZHIAN D 2/829, RAILWAY STATION ST PERUMAL NAICKEN PALAYAM 1 8903739190 GUMMIDIPUNDI MELPATTAMBAKKAM PO,PANRUTTI TK CUDDALORE DIST Pincode:607104 Roll.No:17SKGU3031 Thiru.BHARATH KUMAR P S/o. Thiru.PONNURENGAM 950 44TH BLOCK 2 SATHIYAMOORTHI NAGAR 9789826462 GUMMIDIPUNDI VYASARPADI CHENNAI Pincode:600039 Roll.No:17SKGU4002 Thiru.ANANDH B S/o. Thiru.BALASUBRAMANIAN K 2/157 NATESAN NAGAR 3 3RD STREET 9445516645 GUMMIDIPUNDI IYYPANTHANGAL CHENNAI Pincode:600056 Roll.No:17SKGU4004 Thiru.BHARATHI VELU C S/o. Thiru.CHELLAN 286 VELAPAKKAM VILLAGE 4 PERIYAPALAYAM PO 9789781793 GUMMIDIPUNDI UTHUKOTTAI TK THIRUVALLUR DIST Pincode:601102 Roll.No:17SKGU4006 Thiru.ILAMPARITHI P S/o. Thiru.PARTHIBAN A 133 BLA MURUGAN TEMPLE ST 5 ELAPAKKAM VILLAGE & POST 9952053996 GUMMIDIPUNDI MADURANDAGAM TK KANCHIPURAM DT Pincode:603201 Roll.No:17SKGU4008 Thiru.ANANTH P S/o. Thiru.PANNEER SELVAM S 10/191 CANAL BANK ROAD 6 KASTHURIBAI NAGAR 9940056339 GUMMIDIPUNDI ADYAR CHENNAI Pincode:600020 Roll.No:17SKGU4010 Thiru.VIJAYAKUMAR R S/o. Thiru.RAJENDIRAN TELUGU COLONY ROAD 7 DEENADAYALAN NAGAR 9790303527 GUMMIDIPUNDI KAVARAPETTAI THIRUVALLUR DIST Pincode:601206 Roll.No:17SKGU4011 Thiru.ULIS GRANT P S/o. Thiru.PANNEER G 68 THAYUMAN CHETTY STREET 8 PONNERI 9791745741 GUMMIDIPUNDI THIRUVALLUR THIRUVALLUR DIST Pincode:601204 Roll.No:17SKGU4012 Thiru.BALAMURUGAN S S/o. Thiru.SUNDARRAJAN N 23A,EGAMBARAPURAM ST 9 BIG KANCHEEPURAM 9698307081 GUMMIDIPUNDI KANCHEEPURAM DIST Pincode:631502 Roll.No:17SKGU4014 Thiru.SARANRAJ M S/o. Thiru.MUNUSAMY K 5 VOC STREET 10 DR. -

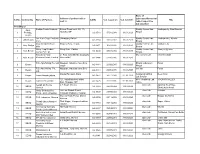

S.L.No. Commodity Name of Packers Address of Packers with E- Mail Id

Name of Address of packers with e- Laboratory/Comercial S.l.No. Commodity Name of Packers CA No. C.A. issued on C.A. valid till TBL mail id /SGL/Cooperative Lab attached R.O.Bhopal Aata, Poddar Foods Products Behind Rewa hotel, NH- 78, Quality Control Lab Vindhyavelly, Maa Birasani 1 Porridge, Shahdol, MP A/2 3518 07.08.2018 31.03.2023 Bhopal Besan Lav Kush Corp. Products Gairatganj, Raisen Quality Control Lab Vindhya velly, Ajiveka 2 Atta Besan A/2-3384 11.10.2013 31.03.2023 Com. Bhopal Maa GAYATRI Flour Khajuria Bina, Dewas Quality control Lab, Vindya Velly 3 Atta, Daliya A/2 3471 15.09.2016 31.03.2021 Mills Bhopal Sironj Crop Produce Sironj Distt- Vidisha Quality Control Lab Sironj & Ajjevika 4 Atta, Besan A/2-3404 03.03.2014 31.03.2019 Comp. Pvt. Ltd Bhopal Kaila Devi Food 21 Ram Janki Mandir Jiwajiganj Morena Ana Lab Chambal Gold 5 Atta, Besan Products Private Limited Morena MP A/2 3464 22/06/2016 31.03.2021 R.B. Agro Milling Pvt. Ltd. Naugaon Industries Area Bina, Bhopal Laboratory Paras 6 Besan A/2-3444 26/06/2015 31/03/2020 Sagar Bhopal R.B. Agro Milling Pvt. Naugoan, Industrial area,Bina own lab Paras 7 Besan A/2-3444 29.05.2015 31.03.2020 Ltd. Mauza Ramgarh, Datia Gwaliar Analytical Deep Gold 8 Besan Tiwari Masala Udyog A/2 3477 14.12.2016 31..03.2021 Lab,Gwaliar 121, Industrial Area, Maksi, MPP. Analytical Lab VINDHYA VALLEY 9 Besan Lakshmi Besan Mill A/2 3476 20.10.2016 31..03.2021 Distt. -

Tender Notice-English 36 RMSA Works 29.12.2015

p PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT BUILDING ORGANISATION OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDING ENGINEER, PWD., BUILDINGS (CONSTRUCTION AND MAINTENANCE) CIRCLE, CHEPAUK, CHENNAI-5. SHORT TERM TENDER NOTICE No. 22 BCM/2015-16/DO2/T1/208 M/DATED:29.12.2015. FORM OF CONTRACT: LUMPSUM # # # For and on behalf of the Governor of Tamil Nadu, Sealed tenders will be received by the Superintending Engineer, PWD., Buildings (Construction and Maintenance) Circle, Chepauk, Chennai-5 for the following works:- Name of work Approximate Class of Cost of EMD and value of work Registration tender Cost of Tender (Rs. in lakhs) as per new documents documents to Sl.No. Regulation with VAT be credited in (in Rupees) favour of Period of of Period Completion 1. Construction of upgraded School Rs.150.00 Class I Rs.15,000/- Executive Engineer, building (Type-II & Sec-II) under Lakhs + PWD.,Buildings RMSA Scheme in Government High Rs.750/- (C&M ) Division Kancheepuram School at Thimmapuram in 8 Acharapakkam block of Months Kancheepuram District EMD Rs.85,000/- 2. Construction of upgraded School Rs.153.00 Class I Rs.15,000/- Executive Engineer, building (Type-II & Sec-II) under Lakhs + PWD., Buildings RMSA Scheme in Government High Rs.750/- (C&M ) Division School at Kadukkalur in Chithamur 8 Kancheepuram block of Kancheepuram District Months EMD Rs.86,500/- 3. Construction of upgraded School Rs.150.00 Class I Rs.15,000/- Executive Engineer, building (Type-II & Sec-II) under Lakhs + PWD., Buildings RMSA Scheme in Government High Rs.750/- (C&M ) Division Kancheepuram School at Karanai Puducheri in 8 Kattankolathur block of Months Kancheepuram District EMD Rs.85,000/- 4. -

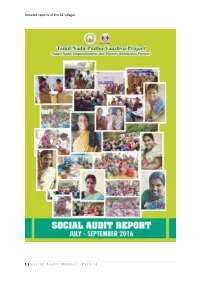

Social Audit Report: Part II

Detailed reports of the 62 villages 1 | Social Audit Report: Part II Detailed reports of the 62 villages SOCIAL AUDIT REPORT PART II: DETAILED REPORTS November 2016 2 | Social Audit Report: Part II Detailed reports of the 62 villages Contents 1. Ariyalur District ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Sendurai village, Sendurai block, Ariyalur District ........................................................................ 6 1.2 Viluppanankurichi village, Thirumanur block, Ariyalur District .................................................... 8 1. Coimbatore district ....................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Periyapodu Village, Anaimalai Block, Coimbatore District ......................................................... 10 2.2 Nachipalayam Village, Madukkarai Block, Coimbatore District .................................................. 13 2.3 Puliyampatti village, Palladam block, Coimbatore district ......................................................... 16 3. Cuddalore district .......................................................................................................................... 20 3.1 Nedunkulam village, Mangalore block, Cuddalore ..................................................................... 20 3.2 T.V.Puthur village, Viruthachalam block, Cuddalore ............................................................ 21 4. Dharmapuri -

Water Matters

Water Matters Annual Report 2017 DHAN Foundation Water Matters Perspectives, Principles and Practices of DHAN’s Water Initiatives “The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way people treat the environment”. - Mahatma Gandhiji “Anyone who can solve the problems of water will be worthy of two Nobel prizes, one for peace and one for science.” - John F. Kennedy PERSPECTIVES Water and Life Water is elixir of life. Water is everywhere on our planet, in the air, in our bodies, in our food and in our breath. Without it life as we know it would not be possible. Saint Poet Tiruvalluvar wrote about the water and the impact of its presence and absence 2000 years ago in the following lines: “It is the unfailing fall of rain that sustains the world. Therefore, look upon rain as the elixir of life”. “Unless raindrops fall from the sky, Not a blade of green grass will rise from the earth”. “No life on earth can exist without water, And the ceaseless flow of that water cannot exist without rain”. “Rain produces man’s wholesome food; And rain itself forms part of his food besides”. “Though oceanic waters surround it, the world will be deluged By hunger’s hardships if the billowing clouds betray us”. Monsoons are the primary source of water for sustaining life in the Indian context. Also, the monsoon causes problems to human life here. Saint Poet Thiruvalluvar further says, “When clouds withhold their watery wealth, Farmers cease to pull their ploughs”. “It is rain that ruins, and it is rain again That raises up those it has ruined”. -

Use of New Media in Indian Political Campaigning System Rahul K* Amity School of Communication, Amity University, Haryana, India

al Science tic & li P Rahul, J Pol Sci Pub Aff 2016, 4:2 o u P b f l i o c DOI: 10.4172/2332-0761.1000204 l A a Journal of Political Sciences & f n f r a u i r o s J ISSN: 2332-0761 Public Affairs Research Article Open Access Use of New Media in Indian Political Campaigning System Rahul K* Amity School of Communication, Amity University, Haryana, India Abstract From e-mailing and e-commerce to e-governance, internet has brought us all at a single platform leaving the constraints of time and space far behind. The social engagement in socio-politico activities and people’s proactive participation in political agenda is also increased through social media and viral usage of networking. However, our communication process is still in its evolution and in turn its effects can be traced on the socio-economic-political life of the ‘Information Society’. Nonetheless, in a country with cultural complexity and striking inequalities in terms of access and reach, literacy, linguistic and spatial differences, it would be essential to make a study of various aspects involved while discussing the use of social media in political campaigning at a large canvas. Keywords: New media; Political communication; Social media; • After the extensive use of social media during Anna Hazare Campaigning; Internet; Technology Campaign in India and witnessing the success of the same, government and opposition political parties have also started Introduction of New media utilizing this tool to register their influence. It was more than a decade, when internet marked as a powerful In the light of above observations the present study would strive to medium of communication globally. -

Neoliberalizing the Streets of Urban India: Engagements of a Free Market Think Tank in the Politics of Street Hawking

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Geography Geography 2013 NEOLIBERALIZING THE STREETS OF URBAN INDIA: ENGAGEMENTS OF A FREE MARKET THINK TANK IN THE POLITICS OF STREET HAWKING Priyanka Jain University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jain, Priyanka, "NEOLIBERALIZING THE STREETS OF URBAN INDIA: ENGAGEMENTS OF A FREE MARKET THINK TANK IN THE POLITICS OF STREET HAWKING" (2013). Theses and Dissertations--Geography. 14. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/geography_etds/14 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Geography by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies.