Perspectives on Mental Illness in India’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shadows and Light Examining Community Mental Health Competency in North India

Shadows and light examining community mental health competency in North India Kaaren Mathias Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine Epidemiology and Global Health Umeå 2016 Shadows and light Examining community mental health competence in North India Kaaren Mathias Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine Epidemiology and Global Health Umeå University, Sweden 2016 Responsible publisher under Swedish law: the Dean of the Medical Faculty This work is protected by the Swedish Copyright Legislation (Act 1960:729) New Series No. 1856 ISBN: 978-91-7601-588-9 ISSN: 0346-6612 Copyright@2016: Kaaren Mathias Electronic version available at http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Printed by: UmU-tryckservice, Umeå University, Sweden 2016 All the variety, all the charm, all the beauty of life is made up of light and shadow. Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina Photo credit – Front cover – Caleb Smallwood iii iv Circling around God – the Ancient Tower Rainer Maria Rilke I live my life in growing orbits which move out over the things of the world. Perhaps I can never achieve the last, but that will be my attempt. I am circling around God, around the ancient tower and have been circling for a thousand years and I still do not know if I am a falcon, a storm or a great song. Translation: Robert Bly, Selected Poems of Rainer Maria Rilke, A Translation from the German and Commentary by Robert Bly This poem by the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke (who himself journeyed through mental distress) encapsulates the deep human urge to engage in the search for meaning, understanding and ultimately truth. -

A Year Since Abrogation

THE A Year Since Abrogation August 2020 Jammu & Kashmir Solidarity Group Acknowledgements We, the individuals and collectives involved in this report, dedicate this report to the perseverance and spirit of resilience of the people of Jammu & Kashmir. We thank all the organisations and groups involved in the last one-year process of the campaign in solidarity with the people of J&K. Let us dedicate ourselves to the future solidarities between the people of mainland India and J&K. The Commission of Inquiry team also takes this opportunity to thank all the people and organisations who met with us, during our visit to the Kashmir valley in the month of February 2020. We are grateful to each one of you for spending time with us, sharing your experiences and helping our learning and understanding about the impact the devastating political move of August 2019 had on each one of you. To the families of the victims, we are forever indebted to you for agreeing to meet with us and risk re- living the pain – to make sure truth is documented. To the lawyers, journalists, trade unionists, academicians, business community, dal dwellers association, boat owners, Wular lake fishers community, Sopore apple growers, saffron farmers, etc., we salute your courage amidst intimidating and often annihilating state terror. We thank the Kashmir Times friends, and families of many of our companions, for the hospitality extended to the team/s. We also acknowledge some members in the administration in Srinagar, who spared time to meet some of the teams. We thank Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, Association of the Parents of the Disappeared Persons, #StandWithKashmir, and many other such platforms and initiatives of Kashmiri people, without whom this campaign or report would have been near impossible. -

MSMNOVDEC05 New for Pdf.Pmd

This Mens Sana Monograph was released at the First International Conference of SAARC Psychiatric Federation, 2nd-4th December 2005 at Agra - India on “Mental Health in South Asia Region - Problems and Priorities.” It was organised by SPF in Collaboration with the Indian Psychiatric Society and Co-sponsored by the World Psychiatric Association. Mens Sana Monographs wish to thank the organisers, Dr. U. C. Garg, Agra, Dr. Roy Abraham Kallivayalil, Kottayam, and Dr. J.K. Trivedi, Lucknow, for arranging for the release of this monograph on the occasion. The Editors, Mens Sana Monographs MSM Mens Sana Monographs A Monograph Series Devoted To The Understanding Of Medicine, Mental Health, Man, And Their Matrix ISBN 81-89753-12-6 ISSN 0973-1229 Vol. III, No. 4-5 Nov. 2005-Feb. 2006 Editor Ajai R. Singh M.D. Deputy Editor Shakuntala A. Singh Ph.D. Honorary International Editorial Advisory Board V.N.Bagadia M.D. Narendra N.Wig M.D. Sunil Pandya M.S. George E. Vaillant M.D. Anil V. Shah M.D. J.K. Trivedi M.D. Anirudh K.Kala M.D. Nimesh G.Desai M.D. Editorial Correspondence: The Editors, Mens Sana Monographs, 14, Shiva Kripa, Trimurty Road, Nahur, Mulund (West), Mumbai, Maharashtra, 400080. India. Telephone: + 91 022 25682740/ + 91 022 25673897 + 91 022 25618630/ + 91 022 25670235 (Clinic Dr. Ajai Singh) + 91 022 25446555 (Office Dr. Shakuntala Singh) Fax: + 91 022 25690505 (Attn. Dr. Ajai Singh) e-mail: [email protected] http://mensanamonographs.tripod.com We encourage electronic submissions in Microsoft Word. For style requirements, see recent issue. Also available on request in PDF. -

Annual Report 2018-2019

AR-Cover 2019--FINAL FOR PRINTING-CONVERT TO OUTLINE.ai 1 02-05-2019 11:37:19 AR-Cover 2019--FINAL FOR PRINTING-CONVERT TO OUTLINE.ai 2 02-05-2019 11:37:26 ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 Tata Institute of Social Sciences Photographs TISS acknowledges the photographers of all the images included in this Annual Report. Photo credits have been given where information was provided. Page 1, 22, 224, 225: Nagaland Centre Page 4: Saksham Page 9 (Top): Information and Public Relations Department, Chatra Page 9 (Bottom): Vimal Chunni Page 10 (Top), 26, 29 (Bottom), 38, 47, 127, 145 & 174: Mangesh Gudekar Page 14 (Top): Department of Communications, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health Page 21: Neeraj Kumar Page 27 (Bottom) & 167: CEIAR Team Page 29 (Top): Deepa Bhalerao Page 34: Jennifer Mujawar Page 42 & 43: Counselling Centre Page 52: Sudha Ganapathi Cover Design: www.freepik.com © Tata Institute of Social Sciences, 2019 2018–2019 ANNUAL REPORT PRODUCTION TEAM Sudha Ganapathi, Vijender Singh and Gauri Galande Printed at India Printing Works, 42, G.D. Ambekar Marg, Wadala, Mumbai 400 031 Contents DIRECTOR’S REPORT A Community Engaged University Called TISS .........................................................................................................................................1 Engagement with State, Society and the Industry ..................................................................................................................................3 Awards, Fellowships and Recognition ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Bulletin3 2013 DEF Copia

WAPR e-bulletin WAPR MEETINGS & BOARD MEETINGS BANGKOK & LAHORE. WORLD ASSOCIATION for PSYCHOSOCIAL REHABILITATION Volume 33. December. 2013 www.wapr.info 1 WAPR BULLETIN Nº 33 OCTOBER 2013 WAPR BULLETIN Nº 33. TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial: • P.3: President’s Greetings and Report. Afzal Javed. • P. 3 : Greetings form the Editorial Team. Marit Borg. • P. 5 : Human Rights and Psychosocial Rehabilitation. Dr. Ricardo Guinea. Articles: • P. 9 :The 300 Ramayanas and the District Mental Health Programme. Alok Sarin, Sanjeev Jain. • P. 18. ACEH Mental Health In Post Conflicts, Post Tsunami. Dr M P Deva Highlight: • P: 22 :Theatre for recovery: “Compagnie de l’Oiseau‐Mouche” . • P. 24:Fighting stigma. Case Reports: - Taiwan. Mcdonald’s Taiwan discriminates against Down’s patron. - Spain. Down Sindrome Association fights a case of discrimination in a hotel. - Spain. Angela Bachiller has become in the first council with Down syndrome. Reports: • P. 30: 3º WAPR Asia Pacific Conference ”Recent Advances in Rehabilitation, Biological & Social Psychiatry“. Lahore, Pakistan 1-4 November, 2103. Afzal Javed, President WAPR. • P. 32: TAPR Report for 2013 Symposium: Health and well-being Mental Health and Community- Based Model Supporting Mental Disorders Living. Eva Teng (Secretary General of TAPR). • P.35: Armenia: Yerevan Declaration: "Cooperation for mental health improvement". • P. 37: Launch meeting of WAPR Armenia. Yerevan, Armenia; 29 August, 2013 • P. 39: “Rehabilitación Psicosocial”. A Journal on RPS in Spanish. Madrid,España, 29 August, 2013 • P. 40: XI Annual Conference of Fundación Manantial Madrid, Spain; 28th, 29th. November, 2013. Helena de Carlos. • P 42: “Mental Illness, Dual Pathology and Employment”; Murcia, Spain. -

Indian Journal Of

Indian Journal of PsychiatryOFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE INDIAN PSYCHIATRIC SOCIETY ISSN 0019-5545 Honorary Editor Section Editors Mahendra K. Nepal - Nepal Swaminath G. Literary psychiatry: Ajit V. Bhide Mario Maj - Italy Professor and Head, Art and Psychiatry: R. Raguram Mohan K. Issac - Australia Department of Psychiatry, Cultural Psychiatry: Shiv Gautham Pedro Ruiz - USA Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Medical College, R. Srinivasa Murthy - Jordan Kadugondanahalli, Bangalore - 560045 The History Page: T. V. Asokan Ph: 080-23152508/23209217 Rohan Ganguli - USA Mobile: 9845007121 Indian Advisory Board Rudra Prakash- USA Email: [email protected] Sanjay Dube- USA A.B. Ghosh P. Raghurami Reddy Honorary Chief Advisor Sekhar Saxena- Geneva A. K. Agarwal P. K. Dalal Sheila Hollins- UK T. S. Sathyanarayana Rao Abraham Varghese Prasanna Raj Professor and Head, Tony Elliott- UK Department of Psychiatry, Ajit V. Bhide R. Ponnudurai Vijoy K Varma- USA J. S. S. Medical College, Mysore - 570004 Col. G. R. Golechha S.M.Channabasavanna Vikram Patel- UK Mobile: 9845282399 G. G. Prabhu S. C. Malik Email: [email protected] J. W. Sabhaney S. C. Tiwari Distinguished Past Editors Editorial Offi ce K. Kuruvilla Shridhar Sharma N. N. De 1949 to 1951 Department of Psychiatry, K. A. Kumar Narendra N. Wig L. P. Verma 1951 to 1958 J. S. S. Medical College, Hospital, S. Kalyanasundaram R. Sathianathan A. N. Bardhan 1958 to 1960 Ramanuja Road, Mysore – 570004 P. Kulhara Indira Sharma Lt. Col. M. R. Vachha 1961 to 1967 Ph: 0821 -2653845 Ext 309 Direct: 2442840 (Tele), 0821-2433898 (Fax) A. Venkoba Rao 1968 to 1976 Email: [email protected] International Advisory Board B. -

In the Supreme Court of India Curative Petition

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CURATIVE PETITION (C) NO. OF 2014 IN REVIEW PETITION (C) NOS. 221 OF 2014 ARISING OUT OF COMMON ORDER DATED 11.12.2013 PASSED IN CIVIL APPEAL NO. 10972 OF 2013 (ARISING OUT OF SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 15436 OF 2009) IN THE MATTER OF: Dr. Shekhar Seshadri & Others …Petitioners Versus Suresh Kumar Koushal & Others …Respondents WITH I.A. No. of 2014 : An application seeking oral hearing in open court AND I.A. No. of 2014 : An application for stay AND I.A. No. of 2014 : An application for exemption from filing certified copy of the judgment dated 28.1.2014 AND I.A. No. of 2014 : An application for permission to file extended synopsis and list of dates PAPER-BOOK (FOR INDEX KINDLY SEE INSIDE) ADVOCATE FOR THE PETITIONERS: GAUTAM NARAYAN INDEX S. No. Particulars Page Nos. 1. Office Report on Limitation 2. Synopsis and List of Dates 3. Certificate issued by Senior Advocate Mr. C.U.Singh as per Rupa Hurra v. Ashok Hurra 4. Curative Petition with Affidavit 5. Annexure P1: Copy of the final common judgment dated 11.12.2013 passed by this Hon’ble Court titled Suresh Kumar Koushal & Ors. Vs Naz Foundation & Ors. (2014) 1 SCC 1 6. Annexure P2: Order dated 28.1.2014 in the Review Petition (C) No.221 of 2014 7. Annexure P3: Order dated 2.9.2004 in W.P.(C.) No.7455 of 2001 passed by the Hon’ble Delhi High Court 8. Annexure P4: Order dated 3.2.2006 in Civil Appeal No.952 of 2006 arising out of SLP(C) Nos.7217-7218 of 2005 passed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India 9. -

Xiith Plan District Mental Health Programme Prepared by Policy

Policy Group DMHP dated 29th June 2012 XIIth Plan District Mental Health Programme prepared by Policy Group 29th June 2012 GLOSSARY : CMHW – Community Mental Health Worker CHC – Community Health Centre CIT - Central Implementation Team DMHP – District Mental Health Programme DMHCC – District Mental Health Care Committee IDSP – Integrated Disease Survelliance System MHIS – Mental Health Information System MND – Mental and Neurological Disorders MoHFW – Ministry of Health and Family Welfare PHC – Primary Health Centre PwMI – Person with mental illness TSAG – Technical Support and Advisory Group SIT – State Implementation Team SMHCC – State Mental Health Care Committee I.Introduction : 1. The need for a National Mental Health Policy has been highlighted by several stakeholders over the past few years.This was again re-iterated during the consultations conducted by the Ministry on the draft Mental Health Care Bill. In response to this felt need, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) in April 2011appointed a Mental Health Policy Group to frame a national Mental Health Policy and Plan. The Policy Group consists of 11 members from diverse backgrounds and includes mental health professionals, user and care-giver representatives, public health experts and senior officials of the MoHFW (see Appendix I for details about members of the Policy Group and the Terms of Reference of the Policy Group). MoHFW asked the Policy Group to take up the task of designing the DMHP as a matter of priority to be ready for the XIIth Plan period starting on 1st April 2012. The Policy Group was also informed that MoHFW wanted the DMHP expanded to all districts in the country, in a staggered manner, over the XIIth Five Year Plan period (April 2012 – March 2017). -

Capitalism and COVID-19

MAY 2, 2020 Vol LV No 18 ` 110 A SAMEEKSHA TRUST PUBLICATION www.epw.in EDITORIALS Capitalism and COVID-19 Rescuing Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Since long-run solutions to COVID-19 can barely emerge Undemocratic Evasion of from outside the interstate systems, there arises a Environmental Responsibility need to reimagine these systems for letting science FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK and technology flourish without the fetters on their ownership. pages 14, 28 COVID-19 and a Just State? WEEKLY COMMENTARY Analysing Kerala’s Response to Together They Stand the COVID-19 Pandemic By containing the COVID-19 contagion through World Economy and Nation States decentralised, scientific, and humane policies, Kerala post COVID-19 demonstrates the efficacy of participatory governance in COVID-19’s Disruption of India’s Transformed handling calamities. page 10 Food Supply Chains BOOKPOLITICAL REVIEWS Food Supply during COVID-19 & The Psychological Impact of the Partition of India Shadows of Doubt: Stereotypes, Crime, and With the PDS supplying barely 5% of India’s food the Pursuit of Justice consumption, policies should work towards making the private food supply chains rebound, instead of replacing PERSPECTIVES these by government food distribution. page 18 Epidemics and Capitalism SPECIAL ARTICLES Small Business Meets Big Duty Small Businesses, Big Reform: A Survey of the MSMEs Facing GST Debates on the effects of GST on small businesses in ECONOMIC ‘Piloting’ Gender in the Indian Railways: India get a unique evidence base from the primary surveys Women Loco-pilots, Labour and Technology of such enterprises facing this indirect tax reform. page 32 Implementation of Community Forest Ri ghts: Experiences in the Vidarbha Region of Maharashtra An Old Boys’ Club CURRENT STATISTICS The additional hierarchy of “masculine” standards of performance deters women loco-pilots in Indian POSTSCRIPT Railways from fully engaging in their job. -

Mental Health Care Bill,2013

REPORT NO. 74 PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE SEVENTY FOURTH REPORT The Mental Health Care Bill, 2013 (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare) (Presented to the Hon’ble Chairman, Rajya Sabha on 20th November, 2013) (Forwarded to the Hon’ble Speaker, Lok Sabha on 20th November, 2013) (Presented to the Rajya Sabha on 9th December, 2013) (Laid on the Table of Lok Sabha on 9th December, 2013) Rajya Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi December, 2013/Agrahayana, 1935 (Saka) Website : http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail : [email protected] 167 Hindi version of this publication is also available PARLIAMENT OF INDIA RAJYA SABHA DEPARTMENT-RELATED PARLIAMENTARY STANDING COMMITTEE ON HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE SEVENTY FOURTH REPORT The Mental Health Care Bill, 2013 (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (Presented to the Hon’ble Chairman, Rajya Sabha on 20th November, 2013) (Forwarded to the Hon’ble Speaker, Lok Sabha on 20th November, 2013) (Presented to the Rajya Sabha on 9th December, 2013) (Laid on the Table of Lok Sabha on 9th December, 2013) Rajya Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi December, 2013/Agrahayana, 1935 (Saka) CONTENTS PAGES 1. COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE ..................................................................................... (i)-(ii) 2. PREFACE ............................................................................................................................... (iii)-(iv) 3. ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................................... -

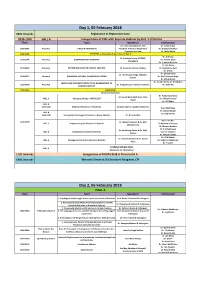

Day 1, 05 February 2018 0800 Onwards Registration at Registration Area 0930-1000 HALL a Inauguration of CME with Keynote Address by Prof

Day 1, 05 February 2018 0800 Onwards Registration at Registration Area 0930-1000 HALL A Inauguration of CME with Keynote Address by Prof. S D Sharma Time Topic Speaker/s Chairperson Dr. J Srinivasaraghavan, Vice Dr. Vinay Kumar 1000-1045 Plenary 1 ETHICS IN PSYCHIATRY President, American Academy of Dr. G Gopalakrishnan Psychiatry and Law Dr. Abdul Majid 1045-1100 TEA BREAK at Hospitality Area in front of Hall A Dr. N N Raju Dr. Sandeep Grover, PGIMER, 1100-1145 Plenary 2 BIOMARKERS IN PSYCHIATRY Dr. Kishore Gujar Chandigarh Dr. S Haque Nizamie Dr. Ajit Bhide 1145-1230 Plenary 3 PSYCHO ONCOLOGY IN CLINICAL PRACTICE Dr. Soumitra S Dutta, Kolkata Dr. Neelanjana Paul Dr. D Ram Dr. Gautam Saha Dr. Om Prakash Singh, NMC&H, 1230-1315 Plenary 4 MANAGING VIOLENCE IN EMERGENCY ROOM Dr. (Col) Harpreet Singh Kolkata Dr. Milind Borde Dr. Vinod K Sinha, Dr. K K Mishra MOLECULAR PSYCHIATRY WITH FOCUS ON RELEVANCE TO 1315-1400 Plenary 5 Dr. K Jagadheesan, Victoria, Australia Dr. Sashi Rai CLINICAL PRACTICE 1400-1445 Lunch Break Concurrent workshop Dr. Arabinda Brahma Dr. Suresh Bada Math & Dr. Nitin HALL A Managing Change – MHCA 2017 Dr. Mahesh Gowda Gupta Dr. CRJ Khess HALL B 1445-1545 Medical Informatics in Psychiatry Surgeon Capt Dr. Kaushik Chatterjee Brig. MSVK Raju Dr. Abhay Matkar HALL B Dr. Tophan Pati 1545-1700 Therapeutic Challenges in Psychosis – Newer Options Dr. G Prasad Rao Prof. T S S Rao 1445-1700 Dr. Mukesh Jagiwala & Dr. Alka HALL C Implementing Sex Education in Schools Dr Kalpana Srivastava Subramaniam Dr Chnimay Barhale Dr. -

![Psychiatry.Org on Monday, March 28, 2011, IP: 210.212.203.211] Indian Journal Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1282/psychiatry-org-on-monday-march-28-2011-ip-210-212-203-211-indian-journal-of-7731282.webp)

Psychiatry.Org on Monday, March 28, 2011, IP: 210.212.203.211] Indian Journal Of

[Downloaded free from http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org on Monday, March 28, 2011, IP: 210.212.203.211] Indian Journal of PsychiatryOFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE INDIAN PSYCHIATRIC SOCIETY ISSN 0019-5545 Honorary Editor Section Editors Mahendra K. Nepal - Nepal Swaminath G. Literary psychiatry: Ajit V. Bhide Mario Maj - Italy Professor and Head, Art and Psychiatry: R. Raguram Mohan K. Issac - Australia Department of Psychiatry, Cultural Psychiatry: Shiv Gautham Pedro Ruiz - USA Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Medical College, R. Srinivasa Murthy - Jordan Kadugondanahalli, Bangalore - 560045 The History Page: T. V. Asokan Ph: 080-23152508/23209217 Rohan Ganguli - USA Mobile: 9845007121 Indian Advisory Board Rudra Prakash- USA Email: [email protected] Sanjay Dube- USA A.B. Ghosh P. Raghurami Reddy Honorary Chief Advisor Sekhar Saxena- Geneva A. K. Agarwal P. K. Dalal Sheila Hollins- UK T. S. Sathyanarayana Rao Abraham Varghese Prasanna Raj Professor and Head, Tony Elliott- UK Department of Psychiatry, Ajit V. Bhide R. Ponnudurai Vijoy K Varma- USA J. S. S. Medical College, Mysore - 570004 Col. G. R. Golechha S.M.Channabasavanna Vikram Patel- UK Mobile: 9845282399 G. G. Prabhu S. C. Malik Email: [email protected] J. W. Sabhaney S. C. Tiwari Distinguished Past Editors Editorial Offi ce K. Kuruvilla Shridhar Sharma N. N. De 1949 to 1951 Department of Psychiatry, K. A. Kumar Narendra N. Wig L. P. Verma 1951 to 1958 J. S. S. Medical College, Hospital, S. Kalyanasundaram R. Sathianathan A. N. Bardhan 1958 to 1960 Ramanuja Road, Mysore – 570004 P. Kulhara Indira Sharma Lt. Col. M. R. Vachha 1961 to 1967 Ph: 0821 -2653845 Ext 309 Direct: 2442840 (Tele), 0821-2433898 (Fax) A.