A Year Since Abrogation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

G2114470 the Religious Factor in The

United Nations A/HRC/47/NGO/2 General Assembly Distr.: General 14 June 2021 English only Human Rights Council Forty-seventh session 21 June–9 July 2021 Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Written statement* submitted by Coordination des Associations et des Particuliers pour la Liberté de Conscience, a non-governmental organization in special consultative status The Secretary-General has received the following written statement which is circulated in accordance with Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. [18 May 2021] * Issued as received, in the language(s) of submission only. GE.21-07886(E) A/HRC/47/NGO/2 The Religious Factor in the Farmers Bills Protests in India It all began last year 2020, with the Farmers Reform Bills of India which were not consulted with the farmers nor were debated in the parliament and were brought to effect without any consultation. This act of PM Modi's government proved that the wealthiest families belonging to Gujrat are aiming to force the entire Indian agriculture under their co- operations, seen by many as Indian farmers being made slaves to big co operations and gradually taking away the ownership of their lands through a systematic process designed by few brilliant greedy individuals and politicians where PM Modi and his team have played a key role in. Under these new reforms, the fundamental right to go to court on contractual disputes, under article 6 and 7 of Universal declaration of human Rights (UDHR) has been taken away from the farmers. -

Noora Kyyrö May 26, 2021 Abstract

Lund University STVK12 Department of Political Science Supervisor: Gustav Agneman Framing for mobilization Content analysis of the Farmers protest’s social media commentary Noora Kyyrö May 26, 2021 Abstract This study examines collective action frames visible in the social media commentary of the ongoing Farmers’ protest in India. It addresses the theoretical and critical questions about social media’s role in the 21st century social movements as well as how framing contributes to mobilization and overcoming the collective action problem. Previous studies have advocated both for and against using social media as a tool to encourage collective action as well as underscored the importance of framing in mobilization. In this thesis, these theoretical arguments are combined and social media’s applicability for discussing collective action frames is analysed. The content analysis of 1400 comments on the Kisan Ekta Morcha’s Facebook page indicates that social media sites can offer opportunities for the general public to engage themselves in the mobilization task of social movements through framing of societal issues. These findings are especially promising for contexts where the mainstream media and/or government is known to advocate against dissident ideas. Keywords: India; Social movements; Mobilization; Framing; Social media Words: 9,998 2 Table of contents 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………….... 4 1.1. Research case and aims ……………………………………… 5 1.2. Relevance ……………………………………………………. 7 2. Background ………………………………………………………..... 8 2.1. Why are the farmers protesting the farm bills ………………. 8 2.2. Kisan Ekta Morcha’s role in the movement ………………… 9 3. Literature Review …………………………………………………. 9 4. Theoretical Framework ……………………………………………. 10 4.1. Connecting social media, collective action, and framing …... -

Exploring Political Imaginations of Indian Diaspora in Netherlands in the Context of Indian Media, CAA and Modi’S Politics

Exploring Political Imaginations of Indian Diaspora in Netherlands In the context of Indian media, CAA and Modi’s politics A Research Paper presented by: Nafeesa Usman India in partial fulfilment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Major: Social Justice Perspectives (SJP) Specialization: Conflict and Peace Studies Members of the Examining Committee: Dr. Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits Dr. Sreerekha Mullasserry Sathiamma The Hague, The Netherlands December 2020 ii Acknowledgments This research paper would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. I would like to thank all my research participants who took out time during these difficult times to share their experiences and thoughts. I would like to thank Dr. Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits, my supervisor, for her valuable comments, and unwavering support. I also thank my second reader, Dr. Sreerekha Sathiamma for her insightful comments. I am grateful for my friends here at ISS and back home for being by my side during difficult times, for constantly having my back and encouraging me to get it done. I am grateful for all the amazing people I met at ISS and for this great learning opportunity. And finally, to my sisters, who made this opportunity possible. Thank you. ii Contents List of Appendices v List of Acronyms vi Abstract vii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Research Problem Statement 1 1.2 Research Questions 2 Chapter 2 Contextual Background 4 2.1 Citizenship Amendment Act 4 2.2 Media role in Nationalist Identity construction -

4 Security Men, 3 Militants Killed in Twin Kreeri Encounters

LAST PAGE...P.8 TUESDAY C AUGUST-2020 KASHMIR M 23 Y SRINAGAR TODAY : PARTLY CLOUDY Contact 18 : -0194-2502327 K FOR SUBSCRIPTIONS & YOUR COPY OF Maximum : 32°c SUNSET Today 07:14 PM Minmum : 21°c SUNRISE Humidity : 58% Tommrow 05:55 AM 27 Zilhijjat-ul-Haraaml | 1441 Hijri | Vol: 23 | Issue: 178 | Pages: 08 | Price: `3 www.kashmirobserver.net twitter.com / kashmirobserver facebook.com/kashmirobserver Postal Regn: L/159/KO/SK/2014-2016 Digest Another Accused Held In Blasphemy Video Case News Chenab Valley Shuts Down, IED Diffused In 4 Security Men, 3 Militants Protesters Block Kashmir Highway Pulwama Press Trust Of India remarks against Prophet of Islam Srinagar- A major tragedy was (Pbuh) went viral on Sunday. averted after Police and security JAMMU: Jammu and Kashmir po- A case has been lodged under forces recovered an IED in South Killed In Twin Kreeri Encounters lice has arrested the third accused section 153A IPC (promoting en- Kashmir’s Pulwama district on Sunday late night. A senior police in connection with a communally mity between different groups) and officer said that IED was planted by sensitive video which had gone vi- 295A IPC (deliberate and malicious militants under a bridge near Tujan Lashkar’s Top Commander Among Slain Militants ral on social media, triggering pro- acts, intended to outrage religious village in Pulwama district, reported tests and shutdown in Chenab val- feelings of any class by insulting its news agency GNS The officer said ley region on Monday, officials said. religion or religious beliefs) at Pacca the bridge is between Tujan and Dal- Haider’s Killing A CRPF ASI Hurt In The overall law and order situa- Danga police station. -

MSMNOVDEC05 New for Pdf.Pmd

This Mens Sana Monograph was released at the First International Conference of SAARC Psychiatric Federation, 2nd-4th December 2005 at Agra - India on “Mental Health in South Asia Region - Problems and Priorities.” It was organised by SPF in Collaboration with the Indian Psychiatric Society and Co-sponsored by the World Psychiatric Association. Mens Sana Monographs wish to thank the organisers, Dr. U. C. Garg, Agra, Dr. Roy Abraham Kallivayalil, Kottayam, and Dr. J.K. Trivedi, Lucknow, for arranging for the release of this monograph on the occasion. The Editors, Mens Sana Monographs MSM Mens Sana Monographs A Monograph Series Devoted To The Understanding Of Medicine, Mental Health, Man, And Their Matrix ISBN 81-89753-12-6 ISSN 0973-1229 Vol. III, No. 4-5 Nov. 2005-Feb. 2006 Editor Ajai R. Singh M.D. Deputy Editor Shakuntala A. Singh Ph.D. Honorary International Editorial Advisory Board V.N.Bagadia M.D. Narendra N.Wig M.D. Sunil Pandya M.S. George E. Vaillant M.D. Anil V. Shah M.D. J.K. Trivedi M.D. Anirudh K.Kala M.D. Nimesh G.Desai M.D. Editorial Correspondence: The Editors, Mens Sana Monographs, 14, Shiva Kripa, Trimurty Road, Nahur, Mulund (West), Mumbai, Maharashtra, 400080. India. Telephone: + 91 022 25682740/ + 91 022 25673897 + 91 022 25618630/ + 91 022 25670235 (Clinic Dr. Ajai Singh) + 91 022 25446555 (Office Dr. Shakuntala Singh) Fax: + 91 022 25690505 (Attn. Dr. Ajai Singh) e-mail: [email protected] http://mensanamonographs.tripod.com We encourage electronic submissions in Microsoft Word. For style requirements, see recent issue. Also available on request in PDF. -

Deeply Disturbing

RNI No: TELENG/2017/72414 a jOurnal Of practitiOners Of jOurnalisM Vol. 5 No. 2 Pages: 32 Price: 20 Deeply Disturbing he Information Technology (Guidelines for Intermediaries APRIL and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 issued by the Union Government in the last week of February is deeply 2021 disturbing for their impact on the constitutionally guaranteed T freedom of expression and the freedom of the press. The government is deceptively projecting them as a grievance redressal mech- anism over the content in social media, OTT video streaming services, and digital news media outlets. It is nobody's case that there should be no regulatory mechanism for the explosively growing social media plat- forms, OTT services, and digital news media platforms and their impact on the people. The clubbing of digital news media outlets with the social media and OTT services are flawed as the news media whether digital, Editorial Advisers electronic, or print h ave the same characteristics as they are manned by working journalists who are trained to verify facts, contextualise, give a S N Sinha perspective to a news story unlike the social media platforms which are K Sreenivas Reddy essentially messaging and communication platforms and use the content Devendra Chintan generated by the untrained and not fact-checked. Likewise, digital media websites have news and editorial desks to function as gate keepe rs to fil- L S Herdenia ter unchecked, unverified, and motivated news before going into the pub- lic domain as in the case of print media. As pointed out in several judg- ments of the apex court, censoring, direct or covert is unconstitutional and undemocratic. -

Farmers' Protest: a Roadmap for the Opposition

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Farmers' Protest: A Roadmap for the Opposition SATYENDRA RANJAN Satyendra Ranjan ([email protected]) is a Delhi-based journalist. Vol. 56, Issue No. 18, 01 May, 2021 The ongoing farmers’ movement in India is proving to be path-breaking in more ways than one. It has unambiguously challenged the political economy of the present Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh–Bharatiya Janata Party regime and has to a limited extent, broken the control of the RSS ecosystem on the political narrative of the country. It has also followed the path of earlier movements such as the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act protests, to present an antithesis to the ideological hegemony of the current ruling arrangement. Though this agitation has had its limitations like earlier protests, it has given hope to the strata of society opposed to the rechristening of Indian nationhood and political system. The ongoing farmers’ movement, against the three new farm laws, was already four months old when the budget session of Parliament began. Those looking forward to a debate on these three laws were disappointed when they were passed hurriedly in the monsoon session of Parliament in September 2020 and the central government refused to conduct a proper discussion on the grievances of farmers, which eventually led to such a powerful agitation. Farmers are of the view that along with the Electricity (Amendment) Bill, 2020, the three laws, namely Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020, the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020, and the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020, would be detrimental to their interests. -

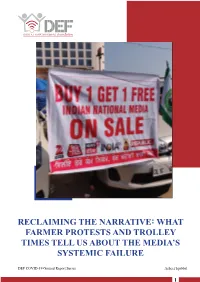

What Farmer Protests and Trolley Times Tell Us About the Media's Systemic Failure

RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE DEF COVID-19 Ground Report Series Asheef Iqubbal RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE 1 DEFDEF COVID-19 COVID-19 Ground Ground Report Report Series Series RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE 2 DEF COVID-19 Ground Report Series DEF COVID-19 GROUND REPORT SERIES: Introduction DEF COVID-19 GROUND REPORT SERIES is a collection of in depth ground reports by the research team of Digital Empowerment Foundation. They have been collecting localised information about the masses and how they are impacted through various situations emerging because of the pandemic. Digital Empowerment Foundation has been intensely working across India with a digital infrastructure across 100 locations. During Covid-19, DEF has a privileged position to be present diversely which helped in bringing a series of ground reports. RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE 3 DEF COVID-19 Ground Report Series RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE : WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE This article was originally published in Newslaundry. It can be accessed here. DEF Ground Report Series. Date of Publication: 15 January 2021 This work is licensed under a creative commons Attribution 4.0 International License. You can modify and build upon document non-commercially, as long as you give credit to the original authors and license your new creation under the identical terms. -

CASIHR Journal on Human Rights Practice Vol. I Issue 2 and Vol. II

CASIHR JHRP Vol. 1 Issue 2, Vol. 2 Issues 1 &2 TABLE OF CONTENTS RESOLVING THE CENSORSHIP PARADOX ................................................................................. 2 ‘ONE MAN’S VULGARITY IS ANOTHER MAN’S LYRIC’: IS IT TIME FOR A NEW TEST OF OBSCENITY? ............................................................................................................................ 1 3 CHANGING CONTOURS OF HOMOSEXUALITY IN INDIA.......................................................... 19 PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS: THE IMPORTANCE OF HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION ..... 35 HUMAN CLONING – LEGAL AND POLICY CONCERNS ............................................................ 46 INTERNATIONAL LAW FOR THE ACTUALIZATION OF THE FREEDOM OF THE PRESS WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON INDIA’S POSITION IN MEETING THE INTERNATIONAL ..................... 63 RE-DEFINING SEDITION IN INDEPENDENT ............................................................................. 75 THE REPUBLIC OF HATE SPEECH AND RELIGIOUS SENTIMENTS .......................................... 94 HATE SPEECH – CHALLENGE TO FREE SPEECH .................................................................. 107 AN ANALYSIS OF FREE SPEECH AND HATE SPEECH AND THE DIFFERENCE, IF ANY, BETWEEN THE TWO ............................................................................................................... 121 “CENSORSHIP” – A NEW WAY TO CLAMP DOWN ON ARTISTIC EXPRESSION .................... 139 A HUMAN RIGHTS ANALYSIS OF REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS ................................................. -

A Pilgrimage with God: Biblical Reflections on Christmas

Journal of Philosophical and Theological Studies July-December 2021 XXIII/2 Contents Editorial: Solidarity and Hope ----------------------------------------- 3 Esther Macedo Chopra ------------------------------------------ 5 The Four Fundamental Principles of Bioethics: Their Need and Relevance for Today Victor Ferrao ------------------------------------------------- 24 Heuretics Modelling as Our Response to the Digital World Anmol Bara ---------------------------------------------------------- 38 Syadvada: A Theory of Relativity of Truth in Jainism Alan T. Sebastian ---------------------------------------------------- 49 Semantic Autonomy of the Text: Towards the Infinity of Meanings Full Issue: www.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4892131 Vidyankur: Journal of Philosophical and Theological Studies is a peer-reviewed interdisciplinary. It is a bi- annual journal published in January and July, seeking to discern wisdom in our troubled times. Inspiring and brief academic articles beneficial to the educated audience are welcome. It attempts to foster personal integration through philosophical search, theological insights, scientific openness and social concern. Editorial Board Dr Kuruvilla Pandikattu SJ, Jnana Deepa, Pune 411014 Dr Ginish C. Baby, Formerly Christ University, Lavasa, Pune Dt Dr Binoy Pichalakkattu, Loyola Institute of Peace and International Studies, Kochi Dr Samuel Richmond, Sam Higginbottom University of Agriculture, Technology & Sciences, Allahabad Dr Shiju Sam Varughese, Central University of Gujarat, Gandhinagar Dr.Shalini Chakranarayan, -

Perspectives on Mental Illness in India’

Report National Seminar on ‘Perspectives on Mental Illness in India’ 1 – 3 July 2010 Venue: Institute of Financial Management and Research (IFMR) Supported by: Navajbai Ratan Tata Trust 1st July 2010 Theme : Access to localised care for persons with mental illness from low socio-economic groups Session 1 Mirjam Dijkxhoorn, Deputy Director, The Banyan Academy of Leadership in Mental Health (BALM) welcomed all the participants of the seminar by elucidating the thought behind getting people together from different sections of mental health sector to present and discuss their views and the themes for each of the three days of the seminar. The Institute of Financial Management and Research were thanked for providing the venue, Oriental Cuisines and Sangeetha Business Hotel were thanked for providing accommodation for speakers and the key partner of BALM, the Navajbai Ratan Tata Trust were thanked for their ongoing support. Prof. Mohan Isaac University of Western Australia/NIMHANS Presentation: Genesis, structure and desired impact of the DMHP The history & genesis of the DMHP was explained. The ‘Bellary experiment’ is the root of the national health programmes. The evolutionary history of DMHP is divided into three phases: Phase I Phase II Phase III Mid 1975 – mid 1985 Mid 1985 – 1990 1995-96 Early age of experimentsPilot programme throughBudget created and innovations PHCs and CHCs From asylum to theBellary experiment 1985 toSteady increase in plan community 1990 allocation 9th, 10th, 11th NMHP approved by central council of Health and Family Welfare. No funds DMHP is now operational in 127 out of 625 districts of India The start of the DMHP collided with recommendations of a WHO expert committee to extend mental health services to community and general health and train human resources for mental health care. -

Ruptured Reality

TIF - Ruptured Reality ANNIE ZAIDI March 5, 2021 Defiant misinformation by the Indian media has deepened the crisis of public trust | YouTube In the Indian mediascape, every mechanism through which fact is sifted from falsehood has become questionable. If news organisations do not have an ethical commitment towards factual reporting, fact-checking risks turning into mere performance. “What kind of reality does truth possess if it is powerless in the public realm?” – Hannah Arendt ‘Ankhon dekhi’, a Hindi phrase referring to an event that one has personally witnessed, was adopted as the title for a 2013 film where Bauji, the middle-aged protagonist, realises that there is a great gulf between what he was told about his daughter’s suitor and what he sees with his own eyes. Henceforth, Bauji refuses to believe anything he has not personally witnessed. He loses his job at a travel agency for he cannot reassure customers that a flight does, in fact, go to its intended destination. He refuses to believe that lions roar until he has heard one roaring. This tragi-comic film is predicated on the practical limits of an individual quest for truth. Society delegates this task to reliable agents: journalists, investigators, and increasingly, recording devices. In the 21st century, however, we find that not only are our human narrators unreliable, we cannot even trust the evidence of devices. Images, video and audio clips are new tools for discombobulation. Take an old video, ascribe to it a new location, and voila! Falsehood emerges, harder and more resilient than truth. Page 1 www.TheIndiaForum.in March 5, 2021 India and the (mis)information superhighway India is one of the world’s more misinformation prone nations.