Noora Kyyrö May 26, 2021 Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

G2114470 the Religious Factor in The

United Nations A/HRC/47/NGO/2 General Assembly Distr.: General 14 June 2021 English only Human Rights Council Forty-seventh session 21 June–9 July 2021 Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Written statement* submitted by Coordination des Associations et des Particuliers pour la Liberté de Conscience, a non-governmental organization in special consultative status The Secretary-General has received the following written statement which is circulated in accordance with Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. [18 May 2021] * Issued as received, in the language(s) of submission only. GE.21-07886(E) A/HRC/47/NGO/2 The Religious Factor in the Farmers Bills Protests in India It all began last year 2020, with the Farmers Reform Bills of India which were not consulted with the farmers nor were debated in the parliament and were brought to effect without any consultation. This act of PM Modi's government proved that the wealthiest families belonging to Gujrat are aiming to force the entire Indian agriculture under their co- operations, seen by many as Indian farmers being made slaves to big co operations and gradually taking away the ownership of their lands through a systematic process designed by few brilliant greedy individuals and politicians where PM Modi and his team have played a key role in. Under these new reforms, the fundamental right to go to court on contractual disputes, under article 6 and 7 of Universal declaration of human Rights (UDHR) has been taken away from the farmers. -

A Year Since Abrogation

THE A Year Since Abrogation August 2020 Jammu & Kashmir Solidarity Group Acknowledgements We, the individuals and collectives involved in this report, dedicate this report to the perseverance and spirit of resilience of the people of Jammu & Kashmir. We thank all the organisations and groups involved in the last one-year process of the campaign in solidarity with the people of J&K. Let us dedicate ourselves to the future solidarities between the people of mainland India and J&K. The Commission of Inquiry team also takes this opportunity to thank all the people and organisations who met with us, during our visit to the Kashmir valley in the month of February 2020. We are grateful to each one of you for spending time with us, sharing your experiences and helping our learning and understanding about the impact the devastating political move of August 2019 had on each one of you. To the families of the victims, we are forever indebted to you for agreeing to meet with us and risk re- living the pain – to make sure truth is documented. To the lawyers, journalists, trade unionists, academicians, business community, dal dwellers association, boat owners, Wular lake fishers community, Sopore apple growers, saffron farmers, etc., we salute your courage amidst intimidating and often annihilating state terror. We thank the Kashmir Times friends, and families of many of our companions, for the hospitality extended to the team/s. We also acknowledge some members in the administration in Srinagar, who spared time to meet some of the teams. We thank Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, Association of the Parents of the Disappeared Persons, #StandWithKashmir, and many other such platforms and initiatives of Kashmiri people, without whom this campaign or report would have been near impossible. -

Exploring Political Imaginations of Indian Diaspora in Netherlands in the Context of Indian Media, CAA and Modi’S Politics

Exploring Political Imaginations of Indian Diaspora in Netherlands In the context of Indian media, CAA and Modi’s politics A Research Paper presented by: Nafeesa Usman India in partial fulfilment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Major: Social Justice Perspectives (SJP) Specialization: Conflict and Peace Studies Members of the Examining Committee: Dr. Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits Dr. Sreerekha Mullasserry Sathiamma The Hague, The Netherlands December 2020 ii Acknowledgments This research paper would not have been possible without the support of many individuals. I would like to thank all my research participants who took out time during these difficult times to share their experiences and thoughts. I would like to thank Dr. Shyamika Jayasundara-Smits, my supervisor, for her valuable comments, and unwavering support. I also thank my second reader, Dr. Sreerekha Sathiamma for her insightful comments. I am grateful for my friends here at ISS and back home for being by my side during difficult times, for constantly having my back and encouraging me to get it done. I am grateful for all the amazing people I met at ISS and for this great learning opportunity. And finally, to my sisters, who made this opportunity possible. Thank you. ii Contents List of Appendices v List of Acronyms vi Abstract vii Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Research Problem Statement 1 1.2 Research Questions 2 Chapter 2 Contextual Background 4 2.1 Citizenship Amendment Act 4 2.2 Media role in Nationalist Identity construction -

4 Security Men, 3 Militants Killed in Twin Kreeri Encounters

LAST PAGE...P.8 TUESDAY C AUGUST-2020 KASHMIR M 23 Y SRINAGAR TODAY : PARTLY CLOUDY Contact 18 : -0194-2502327 K FOR SUBSCRIPTIONS & YOUR COPY OF Maximum : 32°c SUNSET Today 07:14 PM Minmum : 21°c SUNRISE Humidity : 58% Tommrow 05:55 AM 27 Zilhijjat-ul-Haraaml | 1441 Hijri | Vol: 23 | Issue: 178 | Pages: 08 | Price: `3 www.kashmirobserver.net twitter.com / kashmirobserver facebook.com/kashmirobserver Postal Regn: L/159/KO/SK/2014-2016 Digest Another Accused Held In Blasphemy Video Case News Chenab Valley Shuts Down, IED Diffused In 4 Security Men, 3 Militants Protesters Block Kashmir Highway Pulwama Press Trust Of India remarks against Prophet of Islam Srinagar- A major tragedy was (Pbuh) went viral on Sunday. averted after Police and security JAMMU: Jammu and Kashmir po- A case has been lodged under forces recovered an IED in South Killed In Twin Kreeri Encounters lice has arrested the third accused section 153A IPC (promoting en- Kashmir’s Pulwama district on Sunday late night. A senior police in connection with a communally mity between different groups) and officer said that IED was planted by sensitive video which had gone vi- 295A IPC (deliberate and malicious militants under a bridge near Tujan Lashkar’s Top Commander Among Slain Militants ral on social media, triggering pro- acts, intended to outrage religious village in Pulwama district, reported tests and shutdown in Chenab val- feelings of any class by insulting its news agency GNS The officer said ley region on Monday, officials said. religion or religious beliefs) at Pacca the bridge is between Tujan and Dal- Haider’s Killing A CRPF ASI Hurt In The overall law and order situa- Danga police station. -

Deeply Disturbing

RNI No: TELENG/2017/72414 a jOurnal Of practitiOners Of jOurnalisM Vol. 5 No. 2 Pages: 32 Price: 20 Deeply Disturbing he Information Technology (Guidelines for Intermediaries APRIL and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 issued by the Union Government in the last week of February is deeply 2021 disturbing for their impact on the constitutionally guaranteed T freedom of expression and the freedom of the press. The government is deceptively projecting them as a grievance redressal mech- anism over the content in social media, OTT video streaming services, and digital news media outlets. It is nobody's case that there should be no regulatory mechanism for the explosively growing social media plat- forms, OTT services, and digital news media platforms and their impact on the people. The clubbing of digital news media outlets with the social media and OTT services are flawed as the news media whether digital, Editorial Advisers electronic, or print h ave the same characteristics as they are manned by working journalists who are trained to verify facts, contextualise, give a S N Sinha perspective to a news story unlike the social media platforms which are K Sreenivas Reddy essentially messaging and communication platforms and use the content Devendra Chintan generated by the untrained and not fact-checked. Likewise, digital media websites have news and editorial desks to function as gate keepe rs to fil- L S Herdenia ter unchecked, unverified, and motivated news before going into the pub- lic domain as in the case of print media. As pointed out in several judg- ments of the apex court, censoring, direct or covert is unconstitutional and undemocratic. -

Farmers' Protest: a Roadmap for the Opposition

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Farmers' Protest: A Roadmap for the Opposition SATYENDRA RANJAN Satyendra Ranjan ([email protected]) is a Delhi-based journalist. Vol. 56, Issue No. 18, 01 May, 2021 The ongoing farmers’ movement in India is proving to be path-breaking in more ways than one. It has unambiguously challenged the political economy of the present Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh–Bharatiya Janata Party regime and has to a limited extent, broken the control of the RSS ecosystem on the political narrative of the country. It has also followed the path of earlier movements such as the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act protests, to present an antithesis to the ideological hegemony of the current ruling arrangement. Though this agitation has had its limitations like earlier protests, it has given hope to the strata of society opposed to the rechristening of Indian nationhood and political system. The ongoing farmers’ movement, against the three new farm laws, was already four months old when the budget session of Parliament began. Those looking forward to a debate on these three laws were disappointed when they were passed hurriedly in the monsoon session of Parliament in September 2020 and the central government refused to conduct a proper discussion on the grievances of farmers, which eventually led to such a powerful agitation. Farmers are of the view that along with the Electricity (Amendment) Bill, 2020, the three laws, namely Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020, the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020, and the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020, would be detrimental to their interests. -

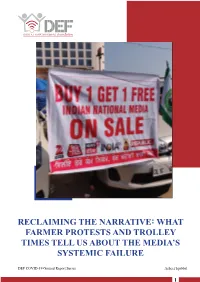

What Farmer Protests and Trolley Times Tell Us About the Media's Systemic Failure

RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE DEF COVID-19 Ground Report Series Asheef Iqubbal RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE 1 DEFDEF COVID-19 COVID-19 Ground Ground Report Report Series Series RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE 2 DEF COVID-19 Ground Report Series DEF COVID-19 GROUND REPORT SERIES: Introduction DEF COVID-19 GROUND REPORT SERIES is a collection of in depth ground reports by the research team of Digital Empowerment Foundation. They have been collecting localised information about the masses and how they are impacted through various situations emerging because of the pandemic. Digital Empowerment Foundation has been intensely working across India with a digital infrastructure across 100 locations. During Covid-19, DEF has a privileged position to be present diversely which helped in bringing a series of ground reports. RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE: WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE 3 DEF COVID-19 Ground Report Series RECLAIMING THE NARRATIVE : WHAT FARMER PROTESTS AND TROLLEY TIMES TELL US ABOUT THE MEDIA’S SYSTEMIC FAILURE This article was originally published in Newslaundry. It can be accessed here. DEF Ground Report Series. Date of Publication: 15 January 2021 This work is licensed under a creative commons Attribution 4.0 International License. You can modify and build upon document non-commercially, as long as you give credit to the original authors and license your new creation under the identical terms. -

CASIHR Journal on Human Rights Practice Vol. I Issue 2 and Vol. II

CASIHR JHRP Vol. 1 Issue 2, Vol. 2 Issues 1 &2 TABLE OF CONTENTS RESOLVING THE CENSORSHIP PARADOX ................................................................................. 2 ‘ONE MAN’S VULGARITY IS ANOTHER MAN’S LYRIC’: IS IT TIME FOR A NEW TEST OF OBSCENITY? ............................................................................................................................ 1 3 CHANGING CONTOURS OF HOMOSEXUALITY IN INDIA.......................................................... 19 PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS: THE IMPORTANCE OF HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION ..... 35 HUMAN CLONING – LEGAL AND POLICY CONCERNS ............................................................ 46 INTERNATIONAL LAW FOR THE ACTUALIZATION OF THE FREEDOM OF THE PRESS WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON INDIA’S POSITION IN MEETING THE INTERNATIONAL ..................... 63 RE-DEFINING SEDITION IN INDEPENDENT ............................................................................. 75 THE REPUBLIC OF HATE SPEECH AND RELIGIOUS SENTIMENTS .......................................... 94 HATE SPEECH – CHALLENGE TO FREE SPEECH .................................................................. 107 AN ANALYSIS OF FREE SPEECH AND HATE SPEECH AND THE DIFFERENCE, IF ANY, BETWEEN THE TWO ............................................................................................................... 121 “CENSORSHIP” – A NEW WAY TO CLAMP DOWN ON ARTISTIC EXPRESSION .................... 139 A HUMAN RIGHTS ANALYSIS OF REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS ................................................. -

A Pilgrimage with God: Biblical Reflections on Christmas

Journal of Philosophical and Theological Studies July-December 2021 XXIII/2 Contents Editorial: Solidarity and Hope ----------------------------------------- 3 Esther Macedo Chopra ------------------------------------------ 5 The Four Fundamental Principles of Bioethics: Their Need and Relevance for Today Victor Ferrao ------------------------------------------------- 24 Heuretics Modelling as Our Response to the Digital World Anmol Bara ---------------------------------------------------------- 38 Syadvada: A Theory of Relativity of Truth in Jainism Alan T. Sebastian ---------------------------------------------------- 49 Semantic Autonomy of the Text: Towards the Infinity of Meanings Full Issue: www.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4892131 Vidyankur: Journal of Philosophical and Theological Studies is a peer-reviewed interdisciplinary. It is a bi- annual journal published in January and July, seeking to discern wisdom in our troubled times. Inspiring and brief academic articles beneficial to the educated audience are welcome. It attempts to foster personal integration through philosophical search, theological insights, scientific openness and social concern. Editorial Board Dr Kuruvilla Pandikattu SJ, Jnana Deepa, Pune 411014 Dr Ginish C. Baby, Formerly Christ University, Lavasa, Pune Dt Dr Binoy Pichalakkattu, Loyola Institute of Peace and International Studies, Kochi Dr Samuel Richmond, Sam Higginbottom University of Agriculture, Technology & Sciences, Allahabad Dr Shiju Sam Varughese, Central University of Gujarat, Gandhinagar Dr.Shalini Chakranarayan, -

Ruptured Reality

TIF - Ruptured Reality ANNIE ZAIDI March 5, 2021 Defiant misinformation by the Indian media has deepened the crisis of public trust | YouTube In the Indian mediascape, every mechanism through which fact is sifted from falsehood has become questionable. If news organisations do not have an ethical commitment towards factual reporting, fact-checking risks turning into mere performance. “What kind of reality does truth possess if it is powerless in the public realm?” – Hannah Arendt ‘Ankhon dekhi’, a Hindi phrase referring to an event that one has personally witnessed, was adopted as the title for a 2013 film where Bauji, the middle-aged protagonist, realises that there is a great gulf between what he was told about his daughter’s suitor and what he sees with his own eyes. Henceforth, Bauji refuses to believe anything he has not personally witnessed. He loses his job at a travel agency for he cannot reassure customers that a flight does, in fact, go to its intended destination. He refuses to believe that lions roar until he has heard one roaring. This tragi-comic film is predicated on the practical limits of an individual quest for truth. Society delegates this task to reliable agents: journalists, investigators, and increasingly, recording devices. In the 21st century, however, we find that not only are our human narrators unreliable, we cannot even trust the evidence of devices. Images, video and audio clips are new tools for discombobulation. Take an old video, ascribe to it a new location, and voila! Falsehood emerges, harder and more resilient than truth. Page 1 www.TheIndiaForum.in March 5, 2021 India and the (mis)information superhighway India is one of the world’s more misinformation prone nations. -

Transcript for Punjabi Farmers Protests and Historic March to Delhi

Transcript for Punjabi Farmers Protests and Historic March to Delhi Welcome to the webinar about Punjabi Farmers Protests and Historic March to Delhi. For the Punjabi Farmers, this protest is extremely detrimental to their lives and to their livelihood. As this issue came into the forefront, we asked our panelists to speak on it, and they kindly obliged. Even with the short duration. I sincerely thank them for their willingness to be on this panel and for their time. I also want to thank our partner, South Asian-Americans Leading Together (SALT) for supporting this webinar and for their work around this issue. I would now like to introduce our incredible moderator, Navraaz Kaur Basati. Navraaz is from the Chicagoland area, and has a background in film production and radio, specifically for non-profit organizations and currently works in the field of conservation, food security and regenerative agriculture. Navraaz? Navraaz: Thank you Kiran and SALDEF for this opportunity for all of us to be able to expand our knowledge on the current situation on the farmers’ protest taking place in India. Before we begin, I’d like to set some expectations and parameters for this session. We will be focusing primarily on the topics that each speaker is presenting on. I’d like to ask the audience that they submit their questions to the Q&A box or the chat box and we will do our best to address those questions within our time constraints at the end of the session. We will also be providing contact information for our speakers so that you can direct questions to them in the future. -

Charda Suraj

AA Ó≈⁄, B@BA ÂØ∫ AG Ó≈⁄ B@BA On our English ؘ≈È≈ ÁΔ¡ª1 language New Â≈˜Δ¡ª ıϪ, Website Ò∂÷ ¡Â∂ ’≈«Ú WWW.PREET ’«ÚÂ≈Úª Ò¬Δ Á∂÷Ø NEWS.COM «È¿±Ô≈’ √≈‚Δ ÚÀÏ√≈¬Δ‡ preetnews2020 www.preetnama.com @gmail.com Óπæ÷ √ßÍ≈Á’ : «ÍzÂÍ≈Ò ’Ω ÍzΔ +1 201-312-4180 √≈Ò D, ¡ß’ IB , «ÓÂΔ : AA Ó≈⁄, B@BA ÂØ∫ AG Ó≈⁄ B@BA ÚÀÏ√≈¬Δ‡ : www.preetnama.com ¬ΔÓ∂Ò [email protected] «Ó¡ªÓ≈ √ø’‡ : √≈˘ Ó∞‹≈‘≈’≈Δ¡ª ¿∞μÂ∂ ◊ØÒΔ ⁄Ò≈¿∞‰ Á∂ ‘∞’Ó «ÁμÂ∂ ◊¬∂ √È - Í∞«Ò√ «Ó¡ªÓ≈ Á∂ Í∞«Ò√ ¡«Ë’≈Δ¡ª È∂ √’≈ Á≈ Â÷Â≈ ÍÒ‡‰≈ ◊Ò √ΔÕ ‹ÁØ∫ ÓÀ∫ ≈ª ˘ √Ω È‘Δ∫ Í≈ «‘≈ √Δ“ ª ÓÀ∫ «¬‘ √Ì Ú∂÷ È≈ √«’¡≈Õ ‘» È∂ Ò¬Δ «’‘≈ «◊¡≈Õ ÌΔÛ “Â∂ ‘ÓÒ≈ ’È Ò¬Δ Áμ«√¡≈ ‘À «’ ¿∞‘ «Í¤Ò∂ Ó‘ΔÈ∂ Â÷Â≈ ÍÒ‡ ÂØ∫ A ÎÚΔ ˘ «Ó¡ªÓ≈ ÁΔ ÎΩ‹, «‹√˘ BB √≈Òª Á∂ ‘» È∂ Áμ«√¡≈ «’ ¿∞‘ ¡Â∂ Áμ«√¡≈ «’ ¿∞‘ Ó؇√≈¬Δ’Ò “Â∂ ‘Δ «¬’μÒ≈ «’‘≈ «◊¡≈Õ ¡√Δ∫ «¬‘ √Ì È‘Δ∫ ’ Í≈¬∂Õ ÁΩ≈È √μÂ≈ “Â∂ ’≈Ï‹ ‘؉ Ú≈Ò∂ ÎΩ‹ Á∂ ‡À‡Ó≈‚Ω «’‘≈ ‹ªÁ≈ ‘À, È∂ √μÂ≈ “Â∂ ’Ï‹≈ ¿∞È∑ª Á≈ «¬μ’ ‘Ø √≈ÊΔ «Ó¡≈Óª ÁΔ¡ª Ìμ‹ ¡≈«¬¡≈Õ ¿∞‘ ’≈ÎΔ ‚«¡≈ ‘Ø«¬¡≈ ¡√Δø Í∞«Ò√ ÁΔ ÈΩ’Δ ˘ Ï‘∞ «Í¡≈ ’Á∂ ¡≈Á∂√ª ˘ Óøȉ ÂØ∫ «¬È’≈ ’È ÂØ∫ Ï≈¡Á ’ΔÂ≈ ‘À, ÒØ’Âø Íμ÷Δ ‘‹≈ª √Û’ª “Â∂ ÍÀ‡Ø«Òø◊ ’ ‘∂ √ÈÕ «‹‘Û∂ √ΔÕ √ΔÕ Í ‘∞‰ √Óª ÏÁÒ ⁄∞μ«’¡≈ ‘ÀÕ √≈≈ «√√‡Ó √‘μÁ Í≈ ’’∂ Ì≈ ÚμÒ Ìμ‹ ◊¬∂ √ÈÕ Ó∞‹≈‘≈’≈Δ √Û’ª “Â∂ ¿∞ ¡≈¬∂ ‘ÈÕ ÍÃÁ√È’≈Δ Ìª‚∂ ÷Û’≈ ’∂ √ªÂÓ¬Δ „ø◊ ÏΔÓ≈ Óª ˘ ¤μ‚ ’∂ ¡≈¬Δ BD √≈Ò≈ ÁΔ ◊Ã∂√ ÏÁÒ ⁄∞μ«’¡≈ ‘ÀÕ ‘∞‰ ¡√Δ∫ «¬‘ ÈΩ’Δ È‘Δ∫ ’∞fi ¡«‹‘Δ¡ª √∞»¡≈ÂΔ «¬ø‡«Ú¿±‹ «Úμ⁄, √∞μ«÷¡≈ ÏÒª “Â∂ E@ ÂØ∫ ÚμË ÒØ’ª ˘ Ó≈È È≈Ò ÍÃÁ√È ’ ‘∂ √È, ¿∞È∑ª ˘ «◊ÃÎÂ≈ «‹È∑ª ÒØ’ª È≈Ò ¡√Δ∫ ◊μÒ ’ΔÂΔ ¿∞È∑ª È∂ ’È≈ ⁄≈‘∞øÁ∂Õ BD √≈Òª ÁΔ ◊Ã∂√ È∂ Áμ«√¡≈ «¬μ’ Á‹È ÂØ∫ ÚμË ¡«Ë’≈Δ¡ª È∂ √≈˘ Á∂ «¬Ò‹≈Ó ÚΔ Òμ◊∂ ‘ÈÕ È≈«¬ø◊ È∂ ’È ÁΔ ËÓ’Δ «ÁμÂΔ ‹≈ ‘Δ √ΔÕ ‘» È∂ Áμ«√¡≈ «’