Guyana and Suriname

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreign Driver's License from Treaty Countries

FOREIGN DRIVER’S LICENSES FROM TREATY COUNTRIES Drivers from treaty countries are allowed to legally drive in Michigan on a foreign driver’s license if the license is printed in English or accompanied with an English translation. Under Michigan law, the driver doesn’t need to show proof of legal presence. • Albania • Ecuador • Macao • San Marino • Algeria • Egypt • Madagascar • Senegal • Argentina • El Salvador • Malawi • Serbia • Australia • Fiji • Malaysia • Seychelles • Austria • Finland • Mali • Sierra Leone • Bahamas • France • Malta • Singapore • Bangladesh • Gambia • Maruitius • Slovak Rep. • Barbados • Georgia • Mexico • Slovenia • Belgium • Germany • Monaco • South Africa • Belize • Ghana • Montenegro • Spain • Benin • Greece • Morocco • Sri Lanka • Botswana • Grenada • Namibia • Suriname • Brazil • Guatemala • Nicaragua • Swaziland • Bulgaria • Guyana • Netherlands • Sweden • Burkina Faso • Haiti • New Zealand • Syrian Arab Rep. • Cambodia • Honduras • Niger • Tanzania • Canada • Hong Kong • Nigeria • Thailand • Central • Hungary • Norway • Togo African Rep. • Iceland • Panama • Trinidad & • Chile • India • Papua New Tobago • China (Taiwan) • Ireland Guinea • Tunisia • Columbia • Israel • Paraguay • Turkey • Congo • Italy • Peru • Uganda • Congo • Jamaica • Philippines • United Arab Democratic Rep. • Japan • Poland Emirates • Costa Rica • Jordan • Portugal • United Kingdom • Cote d’Ivoire • Korea • Romania • Uruguay • Cuba • Kyrgyz Rep. • Russian • Vatican City • Cyprus • Laos Federation • Venezuela • Czech Rep. • Lebanon • Rwanda • Vietnam Rep. • Denmark • Lesotho • St. Lucia • Western Samoa • Dominican • Lithuania • St Vincent & • Zambia Republic • Luxembourg the Grenadines • Zimbabwe FOREIGN DRIVER’S LICENSES FROM NON-TREATY COUNTRIES Drivers from non-treaty countries are allowed to legally drive in Michigan on a foreign driver’s license if: • The driver’s license is printed in English or accompanied with an English translation, and • The driver can show proof of legal presence. -

Guyana: an Overview

Updated March 10, 2020 Guyana: An Overview Located on the north coast of South America, English- system from independence until the early 1990s; the party speaking Guyana has characteristics common of a traditionally has had an Afro-Guyanese base of support. In Caribbean nation because of its British colonial heritage— contrast, the AFC identifies as a multiracial party. the country achieved independence from Britain in 1966. Guyana participates in Caribbean regional organizations The opposition People’s Progressive Party/Civic (PPP/C), and forums, and its capital of Georgetown serves as led by former President Bharrat Jagdeo (1999-2011), has 32 headquarters for the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), a seats in the National Assembly. Traditionally supported by regional integration organization. Indo-Guyanese, the PPP/C governed Guyana from 1992 until its defeat in the 2015 elections. Current congressional interest in Guyana is focused on the conduct of the March 2, 2020, elections. Some Members of Congress have expressed deep concern about allegations of Guyana at a Glance potential electoral fraud and have called on the Guyana Population: 782,000 (2018, IMF est.) Elections Commission (GECOM) to not declare a winner Ethnic groups: Indo-Guyanese, or those of East Indian until the completion of a credible vote tabulation process. heritage, almost 40%; Afro-Guyanese, almost 30%; mixed, 20%; Amerindian, almost 11% (2012, CIA est.) Figure 1. Map of Guyana Area: 83,000 square miles, about the size of Idaho GDP: $3.9 billion (current prices, 2018, IMF est.) Real GDP Growth: 4.1% (2018 est.); 4.4% (2019 est.) (IMF) Per Capita GDP: $4,984 (2018, IMF est.) Life Expectancy: 69.6 years (2017, WB) Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF); Central Intelligence Agency (CIA); World Bank (WB). -

'Good Governance' in the Dutch Caribbean

Obstacles to ‘Good Governance’ in the Dutch Caribbean Colonial- and Postcolonial Development in Aruba and Sint Maarten Arxen A. Alders Master Thesis 2015 [email protected] Politics and Society in Historical Perspective Department of History Utrecht University University Supervisor: Dr. Auke Rijpma Internship (BZK/KR) Supervisor: Nol Hendriks Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2 1. Background ............................................................................................................................ 9 1.1 From Colony to Autonomy ......................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Status Quaestionis .................................................................................................................... 11 Colonial history .............................................................................................................................. 12 Smallness ....................................................................................................................................... 16 2. Adapting Concepts to Context ................................................................................................. 19 2.1 Good Governance ..................................................................................................................... 19 Development in a Small Island Context ........................................................................................ -

Suriname Republic of Suriname

Suriname Republic of Suriname Key Facts __________ OAS Membership Date: 1977 Head of State / Head of Government: President Desire Delano Bouterse Capital city: Paramaribo Population: 597,927 Language(s): Dutch (official), English (widely spoken), Sranang Tongo (native language), Caribbean Hindustani, Javanese Religions: Protestant 23.6%, Hindu 22.3%, Roman Catholic 21.6%, Muslim 13.8%, other Christian 3.2%, Winti 1.8%, Jehovah's Witness 1.2%, other 1.7%, none 7.5%, unspecified 3.2% Ethnic Groups: Hindustani 27.4%, "Maroon" 21.7%, Creole 15.7%, Javanese 13.7%, mixed 13.4%, other 7.6%, unspecified 0.6% Currency: Surinamese dollar (SRD) Gross domestic product (PPP): $8.688 billion (2017 est.) Legal System: civil law system influenced by the Dutch civil codes. The Commissie Nieuw Surinaamse Burgerlijk Wetboek completed drafting a new civil code in February 2009. Political system: Suriname is a presidential republic. The president and vice president are indirectly elected by the National Assembly, where they go on to serve five-year terms without any term limits. The president will serve the Chief of State and the Head of Government. The National Assembly that elects people to these offices consists of 51 members who are directly elected in multi-seat constituencies by party-list proportional representation vote. These members also serve five-year terms. The High Court of Justice of Suriname consists of four members, as well as one court president and vice president. Each of these members are to be appointed by the national president in consultation with the National Assembly, the State Advisory Council, and the Order of Private Attorneys. -

Evaluation of Juvenile Justice Sector Reform Implementation in St. Lucia, St

EVALUATION OF JUVENILE JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM IMPLEMENTATION IN ST. LUCIA, ST. KITTS AND NEVIS, AND GUYANA BASELINE REPORT April 2018 This publication was prepared independently by Dianne Williams, Lily Hoffman, Daniel Sabet, Catherine Caligan, and Meredith Feenstra of Social Impact. It was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development as part of the Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance – Learning, Evaluation, and Research activity. EVALUATION OF JUVENILE JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM IMPLEMENTATION IN ST. LUCIA, ST. KITTS AND NEVIS, AND GUYANA BASELINE REPORT April 2018 AID-OAA-M-13-00011 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ACRONYMS II EXECUTIVE SUMMARY III INTRODUCTION 1 BACKGROUND ON REFORM 2 EVALUATION PURPOSE AND EVALUATION QUESTIONS 5 EVALUATION PURPOSE 5 EVALUATION QUESTIONS 5 USAID PROJECT BACKGROUND 6 EVALUATION DESIGN, METHODS, AND LIMITATIONS 8 EVALUATION DESIGN 8 DATA SOURCES 8 HUMAN SUBJECTS’ PROTECTION 10 SAMPLING 10 DATA ANALYSIS 10 LIMITATIONS 11 FINDINGS & CONCLUSIONS 12 Q1: HAVE MILESTONES IN THE JUVENILE JUSTICE REFORM PROCESS BEEN ACHIEVED? IF NOT, WHY NOT? 12 LEGAL COMPLIANCE 12 COORDINATION IN JUVENILE JUSTICE SERVICE DELIVERY 14 PRE-TRIAL DIVERSION AND ALTERNATIVE SENTENCING PROGRAMS 16 DETENTION FACILITIES 20 REINTEGRATION 23 EXPLAINING THE LACK OF CHANGE 24 CONCLUSION 26 Q2: HOW MANY YOUTHS ARE ENROLLED IN -

Success Codes

a Volume 2, No. 4, April 2011, ISSN 1729-8709 Success codes • NTUC FairPrice CEO : “ International Standards are very important to us.” • Fujitsu innovates with ISO standards a Contents Comment Karla McKenna, Chair of ISO/TC 68 Code-pendant – Flourishing financial services ........................................................ 1 ISO Focus+ is published 10 times a year World Scene (single issues : July-August, November-December) International events and international standardization ............................................ 2 It is available in English and French. Bonus articles : www.iso.org/isofocus+ Guest Interview ISO Update : www.iso.org/isoupdate Seah Kian Peng – Chief Executive Officer of NTUC FairPrice .............................. 3 Annual subscription – 98 Swiss Francs Special Report Individual copies – 16 Swiss Francs A coded world – Saving time, space and energy.. ..................................................... 8 Publisher ISO Central Secretariat From Dickens to Dante – ISBN propels book trade to billions ................................. 10 (International Organization for Uncovering systemic risk – Regulators push for global Legal Entity Identifiers ..... 13 Standardization) No doubt – Quick, efficient and secure payment transactions. ................................. 16 1, chemin de la Voie-Creuse CH – 1211 Genève 20 Vehicle ID – ISO coding system paves the way for a smooth ride ........................... 17 Switzerland Keeping track – Container transport security and safety.. ....................................... -

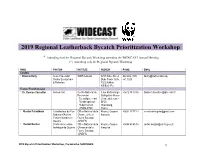

2019 Regional Leatherback Bycatch Prioritization Workshop

2019 Regional Leatherback Bycatch Prioritization Workshop * Attending both the Regional Bycatch Workshop attending the WIDECAST Annual Meeting (*) Attending only the Regional Bycatch Workshop NAME POSITION INSTITUTE ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Canada: * Brianne Kelly Senior Specialist WWF-Canada 5251 Duke Street 902.482.1105 [email protected] Marine Ecosystems Duke Tower Suite ext. 3025 & Fisheries 1202 Halifax NS B3J 1P3 France/ French-Guiane * Dr. Damien Chevallier Researcher Centre National de 3 rue Michel-Ange +0612 97 10 54 [email protected] Recherche Délégation Alsace Scientifique – Inst 23 rue du Loess – Pluridisciplinaire BP20 Hubert Curien Strasbourg, (CNRS-IPHC) France * Nicolas Paranthoën Coordinateur du Plan Office National de la Kourou, Guyane +0694 13 77 44 [email protected] National d'Actions Chasse et de la française Tortues Marines en Faune Sauvage Guyane (ONCFS) * Rachel Berzins Cheffe de la cellule Office National de la Kourou, Guyane +0694 40 45 14 [email protected] technique de Guyane Chasse et de la française Faune Sauvage (ONCFS) 2019 Bycatch Prioritization Workshop, Paramaribo SURINAME 1 * Christelle Guyon Chargée de mission Direction de Rue Carlos +0594 29 68 60 Christelle.guyon@developpement- biodiversité marine l’Environnement, de Fineley CS 76003, durable.gouv.fr l’Aménagement et 97306 Cayenne du Logement Guyane française de Guyane * Nolwenn Cozannet Chargée du projet WWF France, 2, rue Gustave +0594 31 38 28 [email protected] Dauphin de Guyane bureau Guyane Charlery 97 300 CAYENNE -

French Guiana

Country Profile FRENCH GUIANA French Guiana (GF) Geographic Coordinates: 4 00 N, 53 00 W 1 EEZ Extent: 135,048 km 2 (SAUP) Shelf area: 46,741km 2 (SAUP)2 Territorial sea Figure1. COUNTRY MAP Terrestrial extent: 91,000 km 2 Population (2006): 199,509 3 Other countries operating within this: EEZ: Venezuela, Trinidad & Tobago, Suriname Brazil, Barbados Total Landings Description Sited along the northern coast of South America, between Brazil and Suriname, French Guiana borders are demarcated by the Oyapock River in the south and east and the Maroni River in the West. An overseas department of France ( département d'outre-mer ). The Fisheries of French Guiana Overview Commercial shrimp fishing, along with forestry are the most important economic activities and export of shrimp accounts for 50% of export earnings (Weidner et al. 1999). Local fisheries are inshore artisanal canoe fisheries, line fisheries for snappers and commercial shrimp trawling. Foreign-flagged vessels were a significant component of the fishery until the 1990s, when French Guiana waters were closed to US and other international fleets. There are no longline fisheries in French Guiana. 1. What fisheries exist in this territory? The shrimp fishery is dominated by commercial operations fishing for penaeid shrimp, with P. subtilis and P.brasiliensis making up 99% of the catch. Xiphopenaeus kroyeri (seabob) shrimp fishey has not been assessed, and is considered insignificant because of the ban on trawling in the 20 m isobath (Charuau and Medley 2001). Most of the boats are equipped with vessel monitoring systems Red snapper fishery 1 World Fact Book CIA 2006 2 SAUP estimate 3 Worldfact Book CIA 2006 2 2. -

Assessment of Prunus Africana Bark Exploitation Methods and Sustainable Exploitation in the South West, North-West and Adamaoua Regions of Cameroon

GCP/RAF/408/EC « MOBILISATION ET RENFORCEMENT DES CAPACITES DES PETITES ET MOYENNES ENTREPRISES IMPLIQUEES DANS LES FILIERES DES PRODUITS FORESTIERS NON LIGNEUX EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE » Assessment of Prunus africana bark exploitation methods and sustainable exploitation in the South west, North-West and Adamaoua regions of Cameroon CIFOR Philip Fonju Nkeng, Verina Ingram, Abdon Awono February 2010 Avec l‟appui financier de la Commission Européenne Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... i ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................... ii Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Problem statement ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research questions .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Objectives ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Importance of the study ................................................................................... 3 2: Literature Review ................................................................................................. -

Special Update on Quito Process V Technical Meeting on Human

Special update on Quito Process AS OF NOVEMBER 2019 LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN AS OF NOVEMBER 2019 LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN V Technical Meeting on HumanV EMobilityNEZUVELEANNEZUE LofAN Venezuelan Citizens in the RegionREFUGEERSE F&U MGIEGERSA &N TMSIG INR ATNHTES R IENG TIOHNE REGION UNITED STATES UNITED STATES BOGOTA, COLOMBIA Havana\ MEXICO Havana\ MEXICO CUBA DOMINICAN 14-15 NOVEMBER 2019 CUBA DOMINICAN \ REPUBLIC Mexico \ HAITI \ PUERTO REPUBLIC Mexico JAMAICA \ Santo HAITI \ PUERTO City \BELIZE JAMAICA \ RICO City \ Domingo Santo RICO BELIZE Domingo \ HONDURAS CARIBBEAN SEA GUATEMALA \ \ HONDURAS CARIBBEAN SEA \ GUATEMALA \ EL SALVADOR NICARAGUA \ ARUBA CURACAO \ EL SALVADOR APoRrUt BA \NICARAGUA Spain CURACAO Port San José \ \ TRINIDAD Spain \ Panamá San JoséCaracas & TOBA\GO \ TRINIDAD PARTICIPATION COSTA \ \ Caracas Panamá & TOBAGO COSTA \ RICA PANAMA Georgetown RICA PANAMAVENEZUELA \ Georgetown VENEZ\UPaErLaAmaribo \ GUYANA Paramaribo \Bogotá \ CGayUeYnAneNA \ \Bogotá \ Cayenne COLOMBIA SURINAME COLOMBIA FRENCH SURINAME GUYANA FRENCH The fifth round of the Quito Process (Quito V – GUYANA \Quito \Quito ECUADOR Bogota Chapter) took place on 14-15 November ECUADOR (2019), with the participation of 12 States from PERU Latin America and the Caribbean, along with PERU \Lima BRAZIL key cooperating States, international financial \Lima BRAZIL \ BOLIVIA Brasilia \ BOLIVIA Brasilia institutions and other actors. \ \ Sucre Sucre PACIFIC PARAGUAY ATLANTIC PACIFIC PARAGUAY ATLANTIC OCEAN Asunción \ OCEAN The meeting follows up on four previous meetings OCEAN Asunción \ OCEAN QUITO V DECLARATION in September and November 2018, April and July QUITO V DECLARATION SIGNATORIES ARGENTINA SIGNATORIES ARGENTINA 2019, as part of a government-led initiative thatArge ntina \ URUGUAY Argentina \ URUGUAY Santiago \ \ Santiago \ Brazil Buenos Montevideo \ aims to harmonize the policies and practices of Brazil Aires Buenos Montevideo Chile CHILE Aires Chile CHILE the countries in the region. -

Report to Congress

2019 REPORT TO CONGRESS REPORT TO CONGRESS ON PROGRESS OF PUBLIC LAW (P.L.) 114-291: Efforts to Implement the Strategy for U.S. Engagement with the Caribbean Region For more information, please visit: https://www.state.gov/caribbean CONTENTS OVERVIEW 1 SECURITY PILLAR 1 DIPLOMACY PILLAR 2 PROSPERITY PILLAR 3 ENERGY PILLAR 4 EDUCATION PILLAR 5 HEALTH PILLAR 5 DISASTER RESILIENCE 6 ENGAGEMENTS UNDER THE U.S.-CARIBBEAN STRATEGIC ENGAGEMENT ACT, PUBLIC LAW 114-291 9 SECURITY 9 DIPLOMACY 13 PROSPERITY 13 ENERGY 14 EDUCATION 16 HEALTH 18 DISASTER RESILIENCE 19 U.S. Embassy Bridgetown Deputy Public Affairs Officer Gaïna Dávila was pleased Ambassador Sarah-Ann Lynch visits a school in Guyana. to donate books, games, iPads, desktop computers, and materials to the American Corner at the National Public Library, St. John’s, Antigua. Ambassador Karen L. Williams checks out one of the 16 automatic weather stations given to Suriname as part of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) three-year Climate Change Adaptation Project (CCAP) to U.S. Navy Officer does push ups with a girl during USNS Comfort visit to Grenada. build the capacity of regional, national, and local partners to generate and use climate data for decision-making in government and beyond. Army National Guard Band: Over 30 very talented musicians from the U.S. National Guard South Dakota were in Suriname to march in the National Day Parade in 2018. While here, they also had some public performances including at schools. It Ambassador Sarah-Ann Lynch visits American businesses in Guyana. is part of the on-going relationship between Suriname and South Dakota. -

Chapter 4 – Dutch Colonialism, Islam and Mosques 91 4.2

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Constructing mosques : the governance of Islam in France and the Netherlands Maussen, M.J.M. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Maussen, M. J. M. (2009). Constructing mosques : the governance of Islam in France and the Netherlands. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 CHAPTER 4 Dutch colonialism, Islam and mosques 4.1. Introduction The Dutch East Indies were by far the most important Dutch colony. It was also the only colony where a purposeful policy towards Islam was developed and this aspect of Dutch colonial policy in particular attracted attention from other imperial powers. In 1939 the French scholar Georges Henri Bousquet began his A French View of the Netherlands Indies by recalling that: “No other colonial nation governs relatively so many Moslem subjects as do the Netherlands”.