Empowerment for the Pursuit of Happiness: Parents with Disabilities and the Americans with Disabilities Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everything Chicago 3!) 48 .448 Boston 36 53 .4 04

MINERS OUT TO CHECK VETS IN TONIGHT'S GAME Legion and Alaska Juneau Play Tonight—Fast Game 1 Is Forecast by Fans. Britisher American I ... Track Stars Visit President Says%/ CHIEF BENDER iIj The Alaska Juneau club, strength- ened by the addition of one new i Are Mad player, will undertake to stop the Colleges Sport BACK IN BOX winning stride of the American Le- gion in the game tonight at City LONDON, July 22.—That universi- ity as a footballer." Park. The Miners have lo t Field ties overseas have gone mad on Dealing with details of organiza- Captain Brewlek who left town this : LEAGUE port is one of the notes made by tion of the universities, he note: MAJOR week and have gained DeWitt, a Sir Krnest Bain, Chairman of the that in every American university pitcher, who is said to have been Finance Committee of the Leeds Uni- the alumni are well organized and Former Star of Ath- on the hurling staff of a big east- versity, who recently returned from powerful, so powerful as to creati Pitching ern college several years ago. a visit to universities in Canada and in many eases, as not The task of stopping the Vets difficulty they letics, Goes Into Box , (lie United States, in a lengthy re- only lay down conditions upon which seems to tie a tough one. Twice the port lie says in practically every gifts are made to the university for White Sox. Klks, with seven games in succes- university the stadium was pointed but there is an active interference sion to their credit, assayed it and CHICAGO, 22.—After eight out with emphasis, the master of with teaching. -

The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 8 – No 4 20 March , 2012

1 The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 8 – No 4 20 March , 2012 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to sign up for the newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] Name: Dave Shade Career Record: click Alias: Dave Charles Birth Name: Charles D. Shade Nationality: US American Birthplace: Vallejo, CA Hometown: Concord, CA/Pittsfield, MA Born: 1902-03-01 Died: 1983-06-23 Age at Death: 81 Stance: Orthodox Height: 5′ 8″ Manager: Leo P. Flynn The Berkshire Eagle 14 September 1965 FORMER BOXING GREAT Dave Shade discusses his controversial world welterweight championship bout against Mickey Walker while visiting here at the home of his son and daughter-in-law, Mr. and Mrs. William Shade of 263 Barker Road. The fight was held 40 years ago a week from tonight. Walker retained the title, but most newspapermen at ringside felt Shade should have been voted the winner. Shade and his wife drove here from New Smyrna Beach, Fla., where they operate a motel. Shade, now 63, weighs 160 pounds, which was what he weighed in his last fight 30 years ago. 2 Dave Shade, the fellow who was called by many "the uncrowned king of the welterweights," still thinks he licked Mickey Walker for the title 40 years ago next Tuesday night in New York. He said so yesterday in the living room of the home of his son and daughter-in-law, Mr. and Mrs. William Shade of 263 Barker Road, where the 63 year-old former boxer and his wife are spending a vacation from New Smyrna Beach, Fla. -

Collarfor, YOUNG MEN 10

13 TIIE MORXIXG OREGOXIAX, FRIDAY, MARCII 11, 1921 row are: Marsh field vs. McMinnvllle, US, THOUGHT LOST, DARCY REPORTED MATCHED HOPES OF SIX HIGH and Salem vs. Eugene. KIDILL ARRANGES DOUBLE GRIP HOOP SElMI-FIXAL- S today WITH GIBBONS IN TITLE GO SHOWS UP II AUTO SCHOOL FIVES FADE Finals of Xorthwest Tourney at E BOUTS Letter From Portland Middleweight Declares Match Is Main Seattle Due Tomorrow. Event in New York on March 22. SEATTLE, Wash., March 10. Sem- ifinals in the basketball championship series of the Pacific Northwest asso- Southpaw Adds Laurels to BT DICK SHARP. McCarthy has two jobs to fill, now First Round of Basketball ciation of the Amateur Athletic union Main Events for Thursday NFORMATION that Jimmy Darcy. that Carroll is going elsewhere, and of America wilF be played tomorrow he has eight applications. night, and the finals are scheduled Might Are Booked. Traveling Reputation. I Tugged Portland middleweight, Tourney Completed. Saturday night. would battle Tommy Gibbons of Ray Rowher, last year captain of In tonight's games the System Sign St. Paul In the main event of a box- the University of California baseball team of Seattle defeated Renton, ing card at Madison Square garden. team, and Pierce Works, first base- Wash., volunteer fire department, 20 iT New York, March 22, is contained In man of the same team, have been to 16; Battery A, Walla Walla. Wash., m?mr wctfi BEAVERS WORK 4 HOURS a letter received yesterday from signed by the Pittsburg Pirates. The STATE TITLE AT STAKE defeated the Northern Life, Seattle, SHADE TO FIGHT MURPHY Jimmy. -

^G^Polx)-Ati Ii

i 1 THE NE W YORK HERALD, AiONDAY, DEGEMBEK 19, 1921. is __ BOXINGi . BASK)ETBALL -TRAPS.H()OTI>^G^POLX)-ATI II. KIICS f N f mi *.¥ \ ITAUTfm T 111 T\n TIT Cochran vs. Horemans. SPORTS ALLIANCE 1924 Olympic Stadium I i ne mew v,ar R. F.RICE HIGH GUN nunor, LMUdiN FalHno- r.. On/I -1. -1." Just Outside of Paris V J; ! Welker Cochran and ICdouard will continue to play each Horemuuother for a while. To-night tliey will play a ANTi-RICKARD P\IUS, Doe. IS (Associuted Pre.ss). 4ATTRAVRRSTRT.AND11 4 ill I J Ul\l/ 111 V 300 exhibition NOT m i \ BRONX ROAD RACE point game at the Palace i .The stadium where tfie 19-4 Billiard Academy, on Southern Olympic uantea ore tfl be held SNOW 8Lev# The Bronx, and to-morrowBoulevard.and wilt probably be built in the I'arc OP In the and IM A Wednesday afternoon Hostility to Garden Ring: dea Princes, Just outside of Paris, ThkouGH Breaks 94 Out of 100 to Lead Timmermann of St. Jerome they will meet in a 1,200 eveningpoint between the of and Cftack in at Tk Denied at sate AuteilU TH6" contest Madison's Academy, Promoterthe Oate JJoiltor. i£ the GAftA6t Ct>0«. Now York A. C. Men 0. Is First in League street and Broadway, In 300iilxtyslxthpoint of the comm.ssionrecommendationsof ANO LI6HT blocks. Meeting. are approved by the City experts THE" at Traps. Handicap. i .J ell, which is to meet for this purposeCouni next week. The commission, which was ' < WON'T K. -

^Alaska Meat Company!

BRINGING UP FATHER By GEORGE McMANUS A Home Product of Real Merit g> & jf CONFECTIONS and ICE CREAM Are Home Products that all Juncauites are proud of. 11 ,-v L J. SHARICK Jeweler and Optician Watches, Diamonds, ■ • Silverware Jewelry I---■ I--I-,.-ZS FOR CHARTER Lauiuli Earl M Fr*i*ht and PaaoonKor Sarrlo* CALL QUALITY STOKB I ■ l— — ... ^ — ^ Automobile HARTNETT MAKES 1 NOTICE TO CITIZENS. GREB GIVEN DECISION Any person finding broken side MILJUS HOLDS TWO HOMERS IN 1 DEMPSEY AND walks will please notify City Clerk GAME YESTERDAY immediately. Collision , IN FURIOUS BOUT WITH BY ORDER OK STREET BEES TO FIVE CHICAGO, July 3.—Gabby Hart KEARNS STILL COMMITTEE. adv. MICKEY WALKER IN N. Y. nett Immured his eighteenth and Insurance u0 nineteenth of the season in the first Study the store nds—and learn HITS, NO RUNS gnme with St. Louis yesterday after- ON RAD LIST about those new things which are NEW YORK. July 3.— Hairy Greb, scored twice more. The fighting is noon. shown for the first time today. of Pittsburgh, middleweight cham- fast. Walker landed Wilbur Cooper, cub pitcher, made don't tremendously SEATTLE. July :!.— Miljns held Why you take it now and pion, defended his title a one-two and covered himself tt home run. Kearns Fails to and successfully (Ireb Bees to five hits in Appear " the yesterday’s let us the in a furious fifteen round match, and the fighters clinched. Tito ref- Ray Glades, St. Louis outfielder, pay first losj. game and not a Bee crossed the Discuss Between T the main attraction at the Italian eree upset himself The fight- made two home runs, making his Fight again. -

"MARY"CAST PRODUC- the Rate Te Adver- for of Baker

TITE MORNING OREGONIAN, FRIDAY, JUNE 10, 1921 IS tTNER.it. NOT1CE8. bridge of Detroit and Ray Keagris, that he expects to get back on third AMUSEMENTS. BU AXTKT.L In this city. June 8. 10S1 Mrs. the backstroke swimmer from Lros tomorrow. That is, if he can break AMERICAN PROS LOSE RATES FOR Chrlntina Aitell. aged 4t yeare. wife of RECORD STAGES Murphy Al. riMrtlier of Angeles, are to come. SEME in, but the wa has been 0' Henry Axtell. of Portland. going makes the outlook tough. The HEILIGp-riira!- Kvelyn Del Manwell of Vancouver, mm CLASSIFIEr ADVERTISING Wash., and Victor Morgan of Cn Fran- letters AwardedxCieven. score: TflWiriUT OlIC TOMORROW cisco, ("al.. sister of H.irry Hliod"s of Seattle Portland lUiUUIII) J NM.HT Daily or Sunday. Alameda. Cal.. and Curl Kho.lrs of Hono- 9. (Spe- eliminated ix thousand Ull T of Harry FIGHTER BEST ABERDEEN, Wash., June FESTIVAL OF B At B R H O A all -- SPKCIAL PRICE- - One tim .12 per Un lulu. H. and daughter IS cial.) Letters will be awarded to 11 INK Lane, 3.. 2 l'Oenln.m. 2 11 GUINEAS MATCH. Bump advt. two consee- - Rhodes of Hlckrenl. Or. Funeral services 4 OIWolfer.L 0 2 0 MAT, 1 5 DtiTe S2 per will be hel.l at H.ilman s chapel. Third high school baseball men this year, Mld'n.r. TOMORROW, 2; j time lino today (Friday), Mu'y,a-- 3 5 3 Hale, 8., 0 11 Buiue ad vt 3 conMcm- - and Salmon atreets. Coach Harry Craig has announced. -

Ormer Champ Has Entire Boxing World Guessing His Plans

ormer Champ Has Entire Boxing World Guessing His Plans (Wants To Meet Manassa Mauler Loughran, Paulino Offer Jacobs Insists Dempsey { Exhibitions His Chief Interest Now To Stop Jack Or No Pay “Promised” To Box Max New York, Nov 4— (UP)— Mauler, aa first choice (or an Berlin, Not 4—(UP)—Re- Square Garden boxing director, And now the fighters arc be- opponent. gs rdleas of denials from the la confident that the Garden will ginning to talk abont fighting Faullno told Boxing Director United States, doe Jacobs, man* stage Max Schmellng’a next ti- for nothing! James J. Johnston that ho would knock out the former agcr of Mas Schmcllng, main* tig defence Tommy Ijonghran and Paul- that has tlie definite contract with champion or forfeit his purse tains he “Schmellng’a ino I'zcudun made such a to the unemployed! promise of Jade Dempsey to the Garden calls for him to startling proposition at Madi- IiOUKhran duplicated the of- make his first major “come- meet any opponent selected by "I donbt son Square Garden yesterday. fer, then offered to meet Dem- back” attempt against the Ger- ns,’" said Johnston. that we wilt nse him And as If that wasn’t enough to psey, Sharkey or ITzcudun and man champion. against unless Jack first shatter all pugilistic tradition, donate all of his purse to the Dempsey, his a each of the fighters named Jack unemployed regardless of the New York’ Not 4— (UP)— proves ability against Madison Dempsey, one-time Manassa outcome. James J. Johnston, worthy opponent*” Will They Eventually Get Together For This Trophy? The Ring's World Heavyweight Champ.o.. -

International Boxing Research Organization Newsletter #26 September 1987

International Boxing Research Organization Newsletter #26 September 1987 From: Tim Leone Sorry about being a week late on the last Newsletter, but I broke another copyer and it was necessary to have the copy work done by a printing company. To date there has been a total of 90,000 feet of 8mm and S8mm requested for transfer, about 8,000 feet of 16mm and 58 hours of VHS duplication requested. I'm surprised that Castle Films is no longer in business. Again, I must express gratitude to those members who took time to write and phone their encourgement over the resumption of the Newsletter. The organization is a joint venture involving all of us. Without the support of the membership, none of this would be possible. -- Long Live Boxing -- I am involved in doing research in the pre-1932 years of the career of Tiger Jack Fox. At the moment there are numerous verifications of main event matches between the years of 1925 and 1932 for him. Any additional information would be greatly appreciated. In this Newsletter, Thanks must go to the following gentlemen for their contributions: Tracy Callis, Dave Block, Paul Zabala, Bob Soderman, Lawrence Fielding, John Grasso, John Hibner, and Lucketta Davis. 1 V-1 E I F ID I FzECTOFt "V F" 1J A E NEW MEMBERS Jack Barry 33 Skyline Drive West Haven, CT 06516 Phone (203) 933-6651 Mr. Barry is interested in professional boxing from the bareknuckle era to 1959 in the U.S.A. His specific interests include Fritzie Zivic and Harry Greb. -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript JAMA

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript JAMA. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 August 19. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: JAMA. 2014 February 19; 311(7): 682–691. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.93. Effect of Citalopram on Agitation in Alzheimer's Disease – The CitAD Randomized Controlled Trial Anton P. Porsteinsson, MD1,†, Lea T. Drye, PhD2, Bruce G. Pollock, MD, PhD3, D.P. Devanand, MD4, Constantine Frangakis, PhD2, Zahinoor Ismail, MD5, Christopher Marano, MD6, Curtis L. Meinert, PhD2, Jacobo E. Mintzer, MD, MBA7, Cynthia A. Munro, PhD6, Gregory Pelton, MD4, Peter V. Rabins, MD6, Paul B. Rosenberg, MD6, Lon S. Schneider, MD8, David M. Shade, JD2, Daniel Weintraub, MD9, Jerome Yesavage, MD10, Constantine G. Lyketsos, MD, MHS6, and CitAD Research Group 1University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, NY, USA 2Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA 3Campbell Institute, CAMH, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada 4Division of Geriatric Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute and College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, New York, NY, USA 5Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology, Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada 6Johns Hopkins Bayview and Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA 7Clinical Biotechnology Research Institute, Roper St. Francis Healthcare, Charleston, SC, USA 8University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA, USA 9Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA 10Stanford University School of Medicine and VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Stanford, CA, USA Abstract Importance—Agitation is common, persistent, and associated with adverse consequences for patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD). -

The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 8 – No 3 2Nd March , 2012

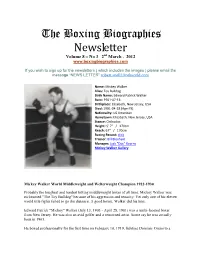

The Boxing Biographies Newsletter Volume 8 – No 3 2nd March , 2012 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to sign up for the newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] Name: Mickey Walker Alias: Toy Bulldog Birth Name: Edward Patrick Walker Born: 1901-07-13 Birthplace: Elizabeth, New Jersey, USA Died: 1981-04-28 (Age:79) Nationality: US American Hometown: Elizabeth, New Jersey, USA Stance: Orthodox Height: 5′ 7″ / 170cm Reach: 67″ / 170cm Boxing Record: click Trainer: Bill Bloxham Manager: Jack "Doc" Kearns Mickey Walker Gallery Mickey Walker World Middleweight and Welterweight Champion 1922-1930 Probably the toughest and hardest hitting middleweight boxer of all time, Mickey Walker was nicknamed "The Toy Bulldog" because of his aggression and tenacity. Yet only one of his eleven world title fights failed to go the distance. A good boxer, Walker did his best. Edward Patrick "Mickey" Walker (July 13, 1903 - April 28, 1981) was a multi-faceted boxer from New Jersey. He was also an avid golfer and a renowned artist. Some say he was actually born in 1901. He boxed professionally for the first time on February 10, 1919, fighting Dominic Orsini to a four round no-decision in his hometown of Elizabeth, New Jersey. Walker did not venture from Elizabeth until his eighteenth bout, he went to Newark. On April 29 of 1919, he was defeated by knockout in round one by K.O. Phil Delmontt, suffering his first defeat. In 1920, he boxed twelve times, winning two and participating in ten no-decisions. -

11R= %Zifii"Imuil=Ttn International Boxing Research Organization

■NWWWWOMMAA00/// NVV1,WWww■m^4440e, alri=77;11r= OM! OEM Old ' blork •10001111.1.6.m.m..4.61.11411 AO.%I %ZifiiImui"l=ttn International Boxing Research Organization BOX 84, GUILFORD, N.Y. 13780 Newsletter #9 November, 1983 WELCOME IBRO welcomes new members Dr. Giuseppe Ballarati, "K.O." Becky O'Neill and Jerome Shochet. Their addresses and description of their boxing interests appear elsewhere in this newsletter. THANKS Thanks to Dave Bloch, Luckett Davis, Laurence Fielding, Herb Goldman, Bruce Harris, Henry Hascup, John Robertson, Johnny Shevalla, Bob Soderman, Julius Weiner and Bob Yalen for material contributed to this newsletter. There was a wealth of material contributed for this issue but unfortunately space considerations caused some to be omitted. Apologies especially to Bob Soderman who contributed an extensive set of corrections for the years 1920 - 24 based on newspaper reports. Hopefully, a special edition of the newsletter can be distributed during the next month to include this information. COMMISSION REPORTS As mentioned in the last newsletter, a request has been made to various state boxing commissions for copies of their official results. A selection of those received is included with this newsletter. Please I et me know your thoughts on having these included with the newsletter. SAMMY BAKER Late additions to the record appearing in this newsletter: (from Luckett Davis) Add: 7/16/24 Bil Williams, Mineola W K OT 1 7/19/24 Sammy Stearns, Mineola W KO 3 7/30/24 Joe Daly, Mineola W KO 1 4/22/25 Pete Hartley, Mineola W PTS 8 10/3/25 Frisco McGale, New York W PTS 10 Change: 7/ /24 Marty Summers to 8/ /24 4//25 Eddie Shevlin to 5//25 and add * indicating newspaper decision / /25 Jack Rappaport - add * indicating newspaper decision / /26 Paul Gulotta - change chronological sequence to between 8/4/26 and 9/8/26 LOUIS "KID" KAPLAN Credit for the record of Louis "Kid" Kaplan appearing in this newsletter was inadvertently omitted. -

Kss Hiolimpairs!

THE SUNDAY OREGOXIAX, PORTLAND, NOVEMBER 13, 1931 3 PRINCIPALS IN FRIDAY NIGHTS MAIN EVENT AT MILWAUKIE. Willi HAS CHANCE WAS1GT11 SQUAD Wish atkturwltdgmtKts to K. C. B, TO MIKE FORTUNE HE6H SCHOOL LEADER Victory Over Wills Means Colonials Win Championship kss a hioL Impairs! Earning of $100,000. in Portland League. HER NICE new busband. STEPPED OUT of the honsa. NEGRO OFTEN UNLUCKY ALL COMERS DEFEATED WHISTLING LIKE a bird. WHICH ALARMED yotme wife, Commerce, Benson and Franklin Fighter Whose Strength Once ANOTHER BIG BOUT BREWS ESPECIALLY WHEN. Place, With ii Cor-bc- tt Tied for Second h P4 pi Frlchtencd Jeffries and SHE FOUND she'd picked Hopes for Big Money. James John in Cellar. DEMPSEY-CAKPENTIE- R MATCH THE WRONG package : h l'OU EUROPE CONSIDERED. AND Standings. INSTEAD of oatmeal BY DICK SHARP. Portland Public School Lrecue W. L. Pet. W. L. Pot HAD birdseed. .Denver Ed Martin stands on the Fight Fans Across Water Do Not Wash'ton.. 0 l.OOO Jcfferson 2 3 GIVEN him threshold of a fortune that was de- Commerce. 3 2 eou i.incoln 1 4 .1MKI nied him in hfs prime 21 years ago. Believe Frenchman Defeated Benson.... 3 2 .OU Jaraea John. V 5 .UUU BUT DO NT think from this, Or, on the threshold of a Franklin... 3 2 .6O0 drop. greatest negro heavy- and Want to lie Shown. This Week's Schedule. The Wednesday, Benson vs. James John: THAT EVERY Rtry. weight in the world In 1S00, Martin Thursday, Jefferson vs. Lincoln; Friday. found It impossible to obtain matches Franklin vi.