The Languages of Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gerry Adams Comments on the Attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin

Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin Friday, March 13, 2009 News Feed Comments ● Home ● About ❍ Note about this website ❍ Contact Us ❍ Representatives ❍ Leadership ❍ History ❍ Links ● Ard Fheis 2009 ❍ Clár and Motions ❍ Gerry Adams’ Presidential Address ❍ Martin McGuinness Keynote Speech on Irish Unity ❍ Keynote Economic Address - Mary Lou McDonald MEP ❍ Pat Doherty MP - Opening Address ❍ Gerry Kelly on Justice ❍ Pádraig Mac Lochlainn North West EU Candidate Lisbon Speech ❍ Minister for Agriculture & Rural Development Michelle Gildernew MP ❍ Bairbre de Brún MEP –EU Affairs ● Issues ❍ Irish Unity ❍ Economy ❍ Education ❍ Environment ❍ EU Affairs ❍ Health ❍ Housing ❍ International Affairs http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (1 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin ❍ Irish Language & Culture ❍ Justice & the Community ❍ Rural Regeneration ❍ Social Inclusion ❍ Women’s Rights ● Help/Join ❍ Help Sinn Féin ❍ Join Sinn Féin ❍ Friends of Sinn Féin ❍ Cairde Sinn Féin ● Donate ● Social Networks ● Campaign Literature ● Featured Stories ● Gerry Adams Blog ● Latest News ● Photo Gallery ● Speeches Ard Fheis '09 ● Videos ❍ Ard Fheis Videos Browse > Home / Featured Stories / Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim March 10, 2009 by admin Filed under Featured Stories Leave a comment Gerry Adams statement in the Assembly Monday March 9, 2009 http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (2 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin —————————————————————————— http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (3 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin Gerry Adams Blog Monday March 9th, 2009 The only way to go is forward On Saturday night I was in County Clare. -

Miscellaneous Notes on Republicanism and Socialism in Cork City, 1954–69

MISCELLANEOUS NOTES ON REPUBLICANISM AND SOCIALISM IN CORK CITY, 1954–69 By Jim Lane Note: What follows deals almost entirely with internal divisions within Cork republicanism and is not meant as a comprehensive outline of republican and left-wing activities in the city during the period covered. Moreover, these notes were put together following specific queries from historical researchers and, hence, the focus at times is on matters that they raised. 1954 In 1954, at the age of 16 years, I joined the following branches of the Republican Movement: Sinn Féin, the Irish Republican Army and the Cork Volunteers’Pipe Band. The most immediate influence on my joining was the discovery that fellow Corkmen were being given the opportunity of engag- ing with British Forces in an effort to drive them out of occupied Ireland. This awareness developed when three Cork IRA volunteers were arrested in the North following a failed raid on a British mil- itary barracks; their arrest and imprisonment for 10 years was not a deterrent in any way. My think- ing on armed struggle at that time was informed by much reading on the events of the Tan and Civil Wars. I had been influenced also, a few years earlier, by the campaigning of the Anti-Partition League. Once in the IRA, our initial training was a three-month republican educational course, which was given by Tomas Óg MacCurtain, son of the Lord Mayor of Cork, Tomas MacCurtain, who was murdered by British forces at his home in 1920. This course was followed by arms and explosives training. -

Revisionism: the Provisional Republican Movement

Journal of Politics and Law March, 2008 Revisionism: The Provisional Republican Movement Robert Perry Phd (Queens University Belfast) MA, MSSc 11 Caractacus Cottage View, Watford, UK Tel: +44 01923350994 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article explores the developments within the Provisional Republican Movement (IRA and Sinn Fein), its politicization in the 1980s, and the Sinn Fein strategy of recent years. It discusses the Provisionals’ ending of the use of political violence and the movement’s drift or determined policy towards entering the political mainstream, the acceptance of democratic norms. The sustained focus of my article is consideration of the revision of core Provisional principles. It analyses the reasons for this revisionism and it considers the reaction to and consequences of this revisionism. Keywords: Physical Force Tradition, Armed Stuggle, Republican Movement, Sinn Fein, Abstentionism, Constitutional Nationalism, Consent Principle 1. Introduction The origins of Irish republicanism reside in the United Irishman Rising of 1798 which aimed to create a democratic society which would unite Irishmen of all creeds. The physical force tradition seeks legitimacy by trying to trace its origin to the 1798 Rebellion and the insurrections which followed in 1803, 1848, 1867 and 1916. Sinn Féin (We Ourselves) is strongly republican and has links to the IRA. The original Sinn Féin was formed by Arthur Griffith in 1905 and was an umbrella name for nationalists who sought complete separation from Britain, as opposed to Home Rule. The current Sinn Féin party evolved from a split in the republican movement in Ireland in the early 1970s. Gerry Adams has been party leader since 1983, and led Sinn Féin in mutli-party peace talks which resulted in the signing of the 1998 Belfast Agreement. -

The Devlinite Irish News, Northern Ireland's "Trapped" Nationalist Minority, and the Irish Boundary Question, 1921-1925

WITHOUT A "DOG'S CHANCE:" THE DEVLINITE IRISH NEWS, NORTHERN IRELAND'S "TRAPPED" NATIONALIST MINORITY, AND THE IRISH BOUNDARY QUESTION, 1921-1925 by James A. Cousins Master ofArts, Acadia University 2000 Bachelor ofArts, Acadia University 1997 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Department ofHistory © James A. Cousins 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission ofthe author. APPROVAL Name: James A. Cousins Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title ofProject: Without a "Dog's Chance:" The Devlinite Irish News, Northern Ireland's "Trapped" Nationalist Minority, and the Irish Boundary Question, 1921-1925 Examining Committee: Chair Dr. Alexander Dawson, Associate Professor Department ofHistory Dr. John Stubbs, Professor Senior Supervisor Department ofHistory Dr. Wil1een Keough, Assistant Professor Supervisor Department ofHistory Dr. Leith Davis, Professor Supervisor Department ofEnglish Dr. John Craig, Professor Internal Examiner Department ofHistory Dr. Peter Hart, Professor External Examiner Department ofHistory, Memorial University of Newfoundland Date Approved: 11 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

PDF(All Devices)

Published by: The Irish Times Limited (Irish Times Books) © The Irish Times 2014. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of The Irish Times Limited, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organisation or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Watching from a window as we all stay the same ................................................................ 4 Emigration- an Irish guarantor of continuity ........................................................................ 7 Completing a transaction called Ireland ................................................................................ 9 In the land of wink and nod ................................................................................................. 13 Rhetoric, reality and the proper Charlie .............................................................................. 16 The rise to becoming a beggar on horseback ...................................................................... 19 The real spiritual home of Fianna Fáil ................................................................................ 21 Electorate gives ethics the cold shoulders ........................................................................... 24 Corruption well known – and nothing was done ................................................................ 26 Questions the IRA is happy to ignore ................................................................................ -

“A Peace of Sorts”: a Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn Mcnamara

“A Peace of Sorts”: A Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn McNamara A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy, Australian National University, March 2017 Declaration ii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank Professor Nicholas Brown who agreed to supervise me back in October 2014. Your generosity, insight, patience and hard work have made this thesis what it is. I would also like to thank Dr Ben Mercer, your helpful and perceptive insights not only contributed enormously to my thesis, but helped fund my research by hiring and mentoring me as a tutor. Thank you to Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Malcolm whose knowledge and experience thoroughly enhanced this thesis. I could not have asked for a better panel. I would also like to thank the academic and administrative staff of the ANU’s School of History for their encouragement and support, in Monday afternoon tea, seminars throughout my candidature and especially useful feedback during my Thesis Proposal and Pre-Submission Presentations. I would like to thank the McClay Library at Queen’s University Belfast for allowing me access to their collections and the generous staff of the Linen Hall Library, Belfast City Library and Belfast’s Newspaper Library for all their help. Also thanks to my local libraries, the NLA and the ANU’s Chifley and Menzies libraries. A big thank you to Niamh Baker of the BBC Archives in Belfast for allowing me access to the collection. I would also like to acknowledge Bertie Ahern, Seán Neeson and John Lindsay for their insightful interviews and conversations that added a personal dimension to this thesis. -

“Colin Duffy Is As Entitled to Due Process As Anyone Else” : Sinn Féin

“Colin Duffy is as entitled to due process as anyone else” : Sinn Féin Friday, March 27, 2009 News Feed Comments ● Home ● About ❍ Note about this website ❍ Accessing our old website ❍ Contact Us ❍ Representatives ❍ History ❍ Leadership ❍ Links ● Ard Fheis 2009 ❍ Clár and Motions ❍ Gerry Adams’ Presidential Address ❍ Martin McGuinness Keynote Speech on Irish Unity ❍ Keynote Economic Address - Mary Lou McDonald MEP ❍ Pat Doherty MP - Opening Address ❍ Gerry Kelly on Justice ❍ Pádraig Mac Lochlainn North West EU Candidate Lisbon Speech ❍ Minister for Agriculture & Rural Development Michelle Gildernew MP ❍ Bairbre de Brún MEP –EU Affairs ● Issues ❍ Irish Unity ❍ Economy ❍ Education ❍ Environment ❍ EU Affairs ❍ Health ❍ Housing http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=995 (1 of 7)27/03/2009 13:54:00 “Colin Duffy is as entitled to due process as anyone else” : Sinn Féin ❍ International Affairs ❍ Irish Language & Culture ❍ Justice & the Community ❍ Rural Regeneration ❍ Social Inclusion ❍ Women’s Rights ● Help/Join ❍ Help Sinn Féin ❍ Join Sinn Féin ❍ Friends of Sinn Féin ❍ Cairde Sinn Féin ● Donate ● Social Networks ● Campaign Literature ● Featured Stories ● Gerry Adams Blog ● Latest News ● Photo Gallery ● Speeches Ard Fheis '09 ● Videos ❍ Ard Fheis Videos Browse > Home / Latest News / “Colin Duffy is as entitled to due process as anyone else” “Colin Duffy is as entitled to due process as anyone else” March 27, 2009 by sinnfein Filed under Latest News Leave a comment “Colin Duffy is as entitled to due process as anyone else” Commenting after Lurgan man Colin Duffy was charged in connection with the attack at Antrim Barracks, Sinn http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=995 (2 of 7)27/03/2009 13:54:00 “Colin Duffy is as entitled to due process as anyone else” : Sinn Féin Féin Assembly member for Upper Bann John O’Dowd has reminded the media that Mr Duffy is entitled to due process and more importantly the presumption of innocence. -

Sinn Féin in 2017

Sinn Féin in 2017 Seamus O’Kane Appearing in these pages this time toxic reputation of Gerry Adams in the three years ago was Kieran Allen’s arti- eyes of a Southern electorate, his poor cle, ‘The Politics of Sinn Féin: Rhetoric performance in leaders’ debates, and an and Reality’1 which provided a clear anal- establishment media opposed to anything ysis of a party whose radical image did to the left of Thatcher (nevermind any- not match their actions. Merely updat- thing republican). ing this article would not be particularly The Assembly election in the North useful as it remains relevant. Indeed, if but a few months later saw a continuation one requires a broad overview of the party of what commentator Chris Donnelly had from a socialist perspective, one would be been describing as ‘nationalist malaise’3 advised to re-read it. It is worth noting, characterised by falling voter turnout and however, the significant gains made by a decline in support for nationalist parties the party since then, both in the North as their traditional support base switched and in the South. off from politics, changed their alle- The 2016 General Election saw Sinn giances, or became outright disillusioned. Féin return to the Dáil with 23 seats, at- Sinn Féin’s drop in support resulted in tracting many of the voters who had been the loss of four incumbents, and a net betrayed by the Labour Party and were loss of one MLA. One of these losses was politicised by the water charges struggle. due to a bizarre decision in Fermanagh This led to them overtaking Labour to be- and South Tyrone to run four candi- come the third largest party for the first dates where only three Sinn Féin seats time since Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin became existed, leading to the loss of incumbent the first Sinn Féin TD to take a Dáil seat Phil Flanagan. -

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard)

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard) Vol u m e 2 (15 February 1999 to 15 July 1999) BELFAST: THE STATIONERY OFFICE LTD £70.00 © Copyright The New Northern Ireland Assembly. Produced and published in Northern Ireland on behalf of the Northern Ireland Assembly by the The Stationery Office Ltd, which is responsible for printing and publishing Northern Ireland Assembly publications. ISBN 0 339 80001 1 ASSEMBLY MEMBERS (A = Alliance Party; NIUP = Northern Ireland Unionist Party; NIWC = Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition; PUP = Progressive Unionist Party; SDLP = Social Democratic and Labour Party; SF = Sinn Fein; DUP = Ulster Democratic Unionist Party; UKUP = United Kingdom Unionist Party; UUP = Ulster Unionist Party; UUAP = United Unionist Assembly Party) Adams, Gerry (SF) (West Belfast) Kennedy, Danny (UUP) (Newry and Armagh) Adamson, Ian (UUP) (East Belfast) Leslie, James (UUP) (North Antrim) Agnew, Fraser (UUAP) (North Belfast) Lewsley, Patricia (SDLP) (Lagan Valley) Alderdice of Knock, The Lord (Initial Presiding Officer) Maginness, Alban (SDLP) (North Belfast) Armitage, Pauline (UUP) (East Londonderry) Mallon, Seamus (SDLP) (Newry and Armagh) Armstrong, Billy (UUP) (Mid Ulster) Maskey, Alex (SF) (West Belfast) Attwood, Alex (SDLP) (West Belfast) McCarthy, Kieran (A) (Strangford) Beggs, Roy (UUP) (East Antrim) McCartney, Robert (UKUP) (North Down) Bell, Billy (UUP) (Lagan Valley) McClarty, David (UUP) (East Londonderry) Bell, Eileen (A) (North Down) McCrea, Rev William (DUP) (Mid Ulster) Benson, Tom (UUP) (Strangford) McClelland, Donovan (SDLP) (South -

PDF (All Devices)

Published by: The Irish Times Limited (Irish Times Books) © The Irish Times 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of The Irish Times Limited, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organisation or as expressly permitted by law. Contents Introduction: ............................................................................................................................... 4 Beyond heroes and villains ........................................................................................................ 4 Contributors to Stories from the Revolution .............................................................................. 6 ‘Should the worst befall me . .’ ................................................................................................ 7 ‘A tigress in kitten’s fur’ .......................................................................................................... 10 Family of divided loyalties that was reunited in grief ............................................................. 13 Excluded by history ................................................................................................................. 16 One bloody day in the War of Independence ........................................................................... 19 Millionaire helped finance War of Independence ................................................................... -

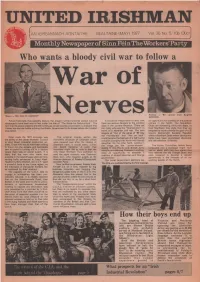

U N I T E D I R I S H M

UNITED IRISHMAN AN tElREANNACH AONTA BEALTAINE (MAY) 1977 Vol. 35 No. 5. lOp (30c) Monthly Newspaper of Sinn Fein The Workers'Party Who wants a bloody civil war to follow a War of Paisley — We cannot trust English Mason — Who does he represent? Nerves politicians. Future historians may possibly declare the present United Unionist Action Council It would be irresponsible to deny that an opportunity for a testing of the political stoppage to have been won or lost under the title of "The Battle for Ballylumford". The there are serious dangers to the working climate in the North. The Republican fact that the power stations are still running as we go to press would seem to Indicate that class in the current situation. There are Clubs are contesting thirty-two seats. In Paisley has lost the battle to bring the British Government to its knees before the Loyalist too many who see the "final solution" in their Manifesto they state that they are population. terms of a sectarian civil war. The twin prepared to work towards the goal of a 32 slogans of "Out of the ashes of '69 rose County Democratic Socialist Republic the Provisionals" and "Not an Inch" within a Northern State where democratic What made the 1974 stoppage was The original cracks within the could become the banners of a right-wing rights have been guaranteed absolutely the ability of the Ulster Workers' Council monolithic structure of Unionism which collusion plunging the North into bloody and sectarianism outlawed. to shut down industrial production en• were papered over after the closing of slaughter. -

13 Lúnasa, 2010 1 NUACHT NÁISIÚNTA Alt Conspóideach Cith Cumhachtach Imithe As Reachtaíocht Úr Ar Dhlí Na Mórshiúlta

www.gaelsceal.ie Feachtas Seanscoil chéanna leanúnach na Seanscéal céanna n-easaontóirí L. 16 poblachtacha Comórtas Tinte ealaíne L. 4 Snámha na le feiscint L. 21 hEorpa L. 29 €1.65 (£1.50) Ag Cothú Phobal na Gaeilge 13.08.2010 Uimh. 21 • Spotaí & Stríocaí IDIRNÁISIÚNTA GRIANGHRAF: MARK STEDMAN/PHOTOCALL IRELAND €100k chun Sleamhnuithe láibe sa tSín gach altra Meadhbh Ní Eadhra TÁTHAR ag maíomh gur thug eolaithe Síneacha rab- hadh 13 bliana ó shin faoin síciatrach mbaol a bhaineann le dífho- raoisiú a dhéanamh i lim- istéir íogaire comhshaoil. Tá gar do 2,000 duine marbh a oiliúint mar gheall ar shleamhnu- ithe láibe sa tír le déanaí. Cé gur báisteach throm ba Ach ní féidir iad a fhostú in Éirinn chúis le formhór na sleamh- nuithe láibe sa tír, tá foinsí Meadhbh Ní Eadhra eolas faoi, ach níl sé de ag rá go raibh siad i bhfad chumhacht acu tuilleadh níos measa mar gheall ar an IN ainneoin go mbeidh na altraí a fhostú. Cuirtear bac dífhoraoisiú. Gearradh céadta altra nua ag cáiliú in orthu mar gheall ar an mhor- 313,000 acra foraoise i Éirinn i gceann seachtaine nó atóir rialtais ata i bhfeidhm.” Zhouqu idir 1952 agus 1990, dhó, tá géarchéim ann i Dar leis an PNA, caithfear ag cur le baol na sleamhnu- measc seirbhísí meabhairsh- na rialacha a bhaineann leis ithe láibe. láinte sa tír seo, dar le tuairisc an moratóir seo a mhaolú a d’fhoilsigh an Comhlachas ionas gur féidir dul i ngleic Altraí Síciatracha (PNA) an leis an ngéarchéim seo. Níl fórsaí na tseachtain seo.