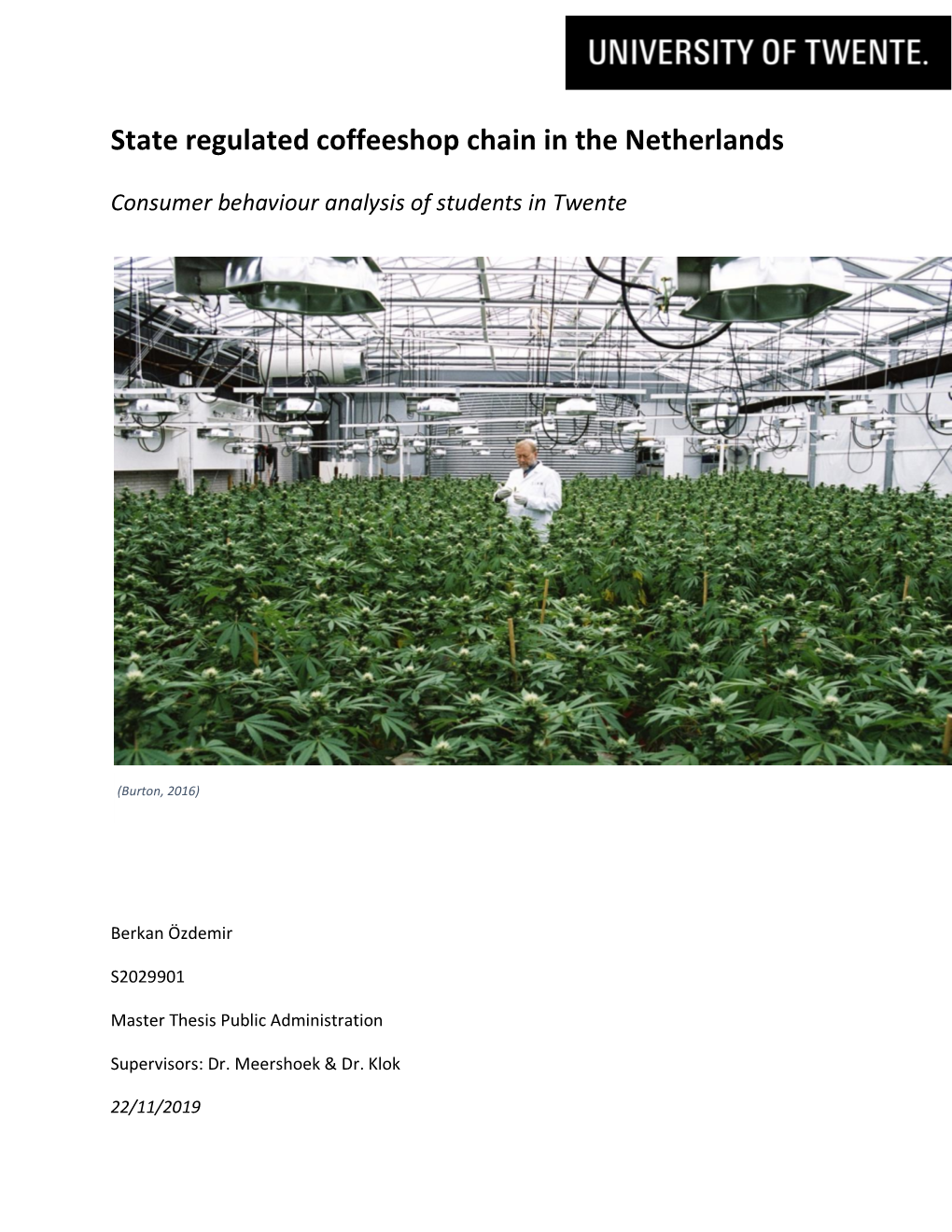

State Regulated Coffeeshop Chain in the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big-Catalogue-English-2020.Pdf

PAS CH SIO UT N D ® CATALOGUE English SEED COMPANY Feminized, autoflower and regular cannabis seeds AMSTERDAM, ESTABLISHED 1987 for recreational and medical use. Amsterdam - Maastricht YOUR PASSION OUR PASSION DUTCH PASSION 02 Contents Welcome to Dutch Passion Welcome to Dutch Passion 02 Dutch Passion was the second Cannabis Seed Company in the world, established in Amsterdam in 1987. It is our mission to supply Bestsellers 2019 02 the recreational and medical home grower with the highest quality cannabis products available in all countries where this is legally Regular, Feminized and Autoflower 03 allowed. Cannabinoids 03 Medical use of cannabis 03 After many years of dedication Dutch Passion remains a leading supplier of the world’s best cannabis genetics. Our experienced Super Sativa Seed Club 04 team do their utmost to maintain the quality of our existing varieties and constantly search for new ones from an extensive network Special Cannabinoids / THC-Victory 05 of worldwide sources. We supply thousands of retailers and seed distributors around the world. Dutch Outdoor 06 High Altitude 09 CBD Rich 10 Dutch Passion have never been afraid to upset conventional thinking; we invented feminized seeds in the 1990’s and more recently Latin America 13 have pioneered the introduction of 10-week Autoflower seeds which have helped make life even easier for the self-sufficient Classics 14 cannabis grower. CBD-rich medical cannabis genetics is a new area that we are proud to be leading. Skunk Family 19 Orange Family 21 The foundation of our success is the genetic control we have over our strains and the constant influx of new genetics that we obtain Blue Family 24 worldwide. -

Considering Marijuana Legalization

Research Report Considering Marijuana Legalization Insights for Vermont and Other Jurisdictions Jonathan P. Caulkins, Beau Kilmer, Mark A. R. Kleiman, Robert J. MacCoun, Gregory Midgette, Pat Oglesby, Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, Peter H. Reuter C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/rr864 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2015 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Marijuana legalization is a controversial and multifaceted issue that is now the subject of seri- ous debate. In May 2014, Governor Peter Shumlin signed Act 155 (S. -

Pink Floyd Amsterdam Coffeeshop

Pink floyd amsterdam coffeeshop Review of Amsterdam coffeeshop Pink Floyd, including atmosphere, pictures, contact, address, feeling and tips for visitors. Pink Floyd was a powerhouse of a coffeeshop in the good old daze of Amsterdam's 90's and naughties! Dampkring 2 is one of my favorite coffeeshops in Amsterdam for many reasons. It's still the same shop, still called Pink Floyd, but with the Dampkring menu. Years ago, Pink Floyd Coffeeshop was considered by many to be one of the best in all of Amsterdam. And while the quality of the service and. 2 reviews of Pink Floyd - CLOSED "This is my favourite coffee shop in the Recommended Reviews for Pink Floyd Best of Yelp Amsterdam – Coffee & Tea. Pink Floyd Coffeeshop. likes · 83 talking about this · were here. 64 Mohamed al Mokled st. right after AWLAD RAGAB Mostafa Alnahas themed. sitting at pink floyd coffeeshop amsterdam smoking. Coffeeshop Amsterdam is the best coffee shop in Amsterdam to truly experience the dutch cannabis culture. Modern interior with extensive menu & great music! Online menus from Coffeeshop Pink Floyd in Amsterdam Netherlands. Pink Floyd was bang opposite our hotel. it was our 1st and last stop . Went to Amsterdam twice and both times my first stop was the Pink Floyd Coffeeshop! great coffeshop! pink floyd album artwork all over the walls. very friendly staff,knowledgable weed men. One of the musts in the Amsterdam coffeeshop scene. then try Pink Floyd's Ummagumma. lol or Zappa on low.. if Dekuil turned it up There really aren't any coffee shops in the Amsterdam centrum and fringe areas. -

The Development of International Drug Control: Lessons Learned and Strategic Challenges for the Future

THE DEVELOPMENT OF INTERNATIONAL DRUG CONTROL: LESSONS LEARNED AND STRATEGIC CHALLENGES FOR THE FUTURE Martin Jelsma * Working Paper Prepared for the First Meeting of the Commission Geneva, 24-25 January 2011 * Martin Jelsma coordinates the Drugs & Democracy programme at the Transnational Institute (TNI) in The Netherlands. He contributed two support papers to the Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy: “The current state of drug policy debate. Trends in the last decade in the European Union and United Nations”, April 2008; and “Legislative Innovation in Drug Policy”, October 2009. The original English text was edited by David Aronson. 1 Abstract The emergence of more pragmatic and less punitive approaches to the drugs issue may represent the beginning of change in the current global drug control regime. The spread of HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users, the overcrowding of prisons, the reluctance in South America to remain a theatre for military anti-drug operations, and the ineffectiveness of repressive anti-drug efforts to reduce the illicit market have all contributed to the global erosion of support for the United States-style war on drugs. Over the last decade rapidly widening cracks have begun to split global drug control consensus. The zero-tolerance ideology is increasingly challenged by calls for decriminalisation, harm reduction and embedding human rights principles in drug control. And in recent years the merits of a regulated legal market for cannabis has been accepted as part of the mainstream debate about a more effective control model. This paper describes how the foundations for the global control system were established, the radicalization of the system toward more repressive implementation, consequently leading to soft defections and de-escalation efforts becoming more widespread; and in the last section projects a future for the ongoing reform process toward a modernization and humanization of the control system’s international legal framework as laid down in the UN drug control conventions. -

Healing Herb Fitness High Stress Less

CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT ® ® WOMEN WEED™ STRESS& LESS HEALING HERB Discover the Marijuana's Calm of CBD Medical Miracles COVID-19 FITNESS HIGH Why the Plant How THC WOMEN & WEED & WOMEN Can Help Boosts Workouts ™ PLUS Is Cannabis CENTENNIAL SPECIALS the Female Viagra? Display Until 4/26/21 $12.99 CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT ® ® WOMEN WEED™ STRESS& LESS HEALING HERB Discover the Marijuana's Calm of CBD Medical Miracles COVID-19 FITNESS HIGH Why the Plant How THC WOMEN & WEED & WOMEN Can Help Boosts Workouts ™ PLUS Is Cannabis CENTENNIAL SPECIALS the Female Viagra? Display Until 4/26/21 $15.99 CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT® WOMEN &WEED™ 2 WOMEN & WEED 3 SECTION 1 34 CANNABIS PRIMER 8 News of the Weed World 14 Words of Weed 54 EDITOR’S LETTER 16 Terpenes & Cannabinoids 20 Seven Studies to Know Now So 2020 was … well, it was 24 State of Disunion something. Between the 28 What’s Legal Where COVID-19 pandemic, murder You Live hornets, civil unrest and an election like no other, it’s no wonder so many of us are SECTION 2 excited to dive headfirst into 2021. And things are looking HEALTH AND WELLNESS good…at least on the cannabis 34 The Wonder Weed front. In this issue, we’ll talk 40 CBD and Stress about how weed won big in the 44 Could CBD Be the November elections, with five Female Viagra? states passing measures to 46 Weed With Your Workout legalize medical or adult-use marijuana and more soon to 50 When Pot Isn’t 28 follow, plus what the Biden Working for You administration means for federal legalization. -

Ten Messages Against Legalization

www.learnaboutsam.org Top 10 Messages Against Legalization* Emphasize the “Big Three” 1. Legalization in Colorado has produced negative consequences – pot gummy bears marketed to kids1, more stoned people on the roads, and more positive workplace drug tests and overall marijuana prevalence. 2 As such, the majority of localities in Colorado have now banned sales. 2. Marijuana legalization will usher in America’s new version of “Big Tobacco.” Already, private holding groups and financiers have raised millions of start-up dollars to promote businesses that will sell marijuana and marijuana-related merchandise. The former head of Strategy for Microsoft has said that he wants to “mint more millionaires than Microsoft” with marijuana and that he wants to create the “Starbucks of marijuana.”3 3. Today’s marijuana is not your Woodstock weed. In the 1960s and ‘70s, THC levels of the marijuana smoked by baby boomers averaged around 1%, increasing to just under 4% in 1983, and almost tripling in the subsequent 30 years to around 14% in 2014.4 Other points: A. More on Colorado. Highlights from 2014, when retail marijuana businesses began operating in Colorado, include, rapid changes in just one year after legalization†: • 32% increase in marijuana-related traffic deaths in just one year from 2013 • Colorado youth usage (ages 12 - 17) ranks 56% higher than the national average • 29% increase in the number of marijuana-related emergency room visits • 38% increase in the number of marijuana-related hospitalizations • Seizures of illegal Colorado marijuana increased another 34% 1. Marijuana is especially harmful to kids and adolescents. • Marijuana contributes to psychosis and schizophrenia5, addiction for 1 in 6 kids who ever use it once6, and it reduces IQ among those who started smoking before age 18.7 • According to data from the 2012 National Survey of American Attitudes on Substance Abuse, alcohol and cigarettes were the most readily accessible substances for youth 12 to 17, with 50% and 44%, respectively, reporting that they could obtain them within a day. -

The Rise and Decline of Cannabis Prohibition the History of Cannabis in the UN Drug Control System and Options for Reform

TRANSNATIONAL I N S T I T U T E THE RISE AND DECLINE OF CANNABIS PROHIBITION THE HISTORY OF CANNABIS IN THE UN DruG CONTROL SYSTEM AND OPTIONS FOR REFORM 3 The Rise and Decline of Cannabis Prohibition Authors Dave Bewley-Taylor Tom Blickman Martin Jelsma Copy editor David Aronson Design Guido Jelsma www.guidojelsma.nl Photo credits Hash Marihuana & Hemp Museum, Amsterdam/ Barcelona Floris Leeuwenberg Pien Metaal UNOG Library/League of Nations Archives UN Photo Printing Jubels, Amsterdam Contact Transnational Institute (TNI) De Wittenstraat 25 1052 AK Amsterdam Netherlands Tel: +31-(0)20-6626608 Fax: +31-(0)20-6757176 [email protected] www.tni.org/drugs www.undrugcontrol.info www.druglawreform.info Global Drug Policy Observatory (GDPO) Research Institute for Arts and Humanities Rooms 201-202 James Callaghan Building Swansea University Financial contributions Singleton Park, Swansea SA2 8PP Tel: +44-(0)1792-604293 This report has been produced with the financial www.swansea.ac.uk/gdpo assistance of the Hash Marihuana & Hemp Museum, twitter: @gdpo_swan Amsterdam/Barcelona, the Open Society Foundations and the Drug Prevention and Information Programme This is an Open Access publication distributed under (DPIP) of the European Union. the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which of TNI and GDPO and can under no circumstances be permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction regarded as reflecting the position of the donors. in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. TNI would appreciate receiving a copy of the text in which this document is used or cited. -

Blunts and Blowt Jes: Cannabis Use Practices in Two Cultural Settings

Free Inquiry In Creative Sociology Volume 31 No. 1 May 2003 3 BLUNTS AND BLOWTJES: CANNABIS USE PRACTICES IN TWO CULTURAL SETTINGS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR SECONDARY PREVENTION Stephen J. Sifaneck, Institute for Special Populations Research, National Development & Research Institutes, Inc. Charles D. Kaplan, Limburg University, Maastricht, The Netherlands. Eloise Dunlap, Institute for Special Populations Research, NDRI. and Bruce D. Johnson, Institute for Special Populations Research, NDRI. ABSTRACT Thi s paper explores two modes of cannabis preparati on and smoking whic h have manifested within the dru g subcultures of th e United States and the Netherlan ds. Smoking "blunts," or hollowed out cigar wrappers fill ed wi th marijuana, is a phenomenon whi ch fi rst emerged in New York Ci ty in the mid 1980s, and has since spread throughout th e United States. A "bl owtj e," (pronounced "blowt-cha") a modern Dutch style j oint whi ch is mixed with tobacco and in cludes a card-board fi lte r and a longer rolling paper, has become th e standard mode of cannabis smoking in the Netherl ands as well as much of Europe. Both are consid ered newer than the more traditi onal practi ces of preparin g and smoking cannabis, including the traditional fi lter-less style joint, the pot pipe, an d the bong or water pipe. These newer styles of preparati on and smoking have implications for secondary preventi on efforts wi th ac tive youn g cannabis users. On a social and ritualistic level th ese practices serve as a means of self-regulating cannabi s use. -

Preparative Isolation of Cannabinoids from Cannabis Sativa by Centrifugal Partition Chromatography

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/244594577 Preparative Isolation of Cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa by Centrifugal Partition Chromatography Article in Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies · December 2004 DOI: 10.1081/JLC-200028170 CITATIONS READS 47 2,645 5 authors, including: Arno Hazekamp Robert Verpoorte Bedrocan BV Leiden University 50 PUBLICATIONS 975 CITATIONS 732 PUBLICATIONS 21,203 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: The effects of inhaled delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) on pain relief and subjective effects in fibromyalgia patients View project All content following this page was uploaded by Robert Verpoorte on 20 June 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Cannabis; extracting the medicine i Arno Hazekamp Cannabis; extracting the medicine Proefschrift Universiteit Leiden ISBN 978-90-9021997-4 Printed by PrintPartners Ipskamp B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands Paper cover: Cannabis Pur 100% (250 grams) from Grafisch Papier, The Nederlands. Photo cover: Dutch medicinal cannabis, variety “Bedrocan”. ii Cannabis; extracting the medicine Proefschrift Ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. mr. P. F. van der Heijden, hoogleraar in de faculteit der Rechtsgeleerdheid, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 5 september 2007 klokke 15.00 uur door Arno Hazekamp Geboren op 15 maart 1976 te Bilthoven iii Promotiecommissie Promotor Prof. dr. R. Verpoorte Referent Dr. C. Giroud (Institut Universitaire de Médecine Légale, Lausanne, Switzerland) Overige leden Prof. -

The Official High Times Cannabis Cookbook: More Than 50 Irresistible Recipes That Will Get You High

CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION TO CANNABIS COOKERY CHAPTER 1: Active Ingredients Basic Recipes THC Oil (Cannabis-Infused Oil) Cannacoconut Oil Cannabis-Infused Mayonnaise Simple Cannabutter Long-Simmering Cannabutter Wamm Marijuana Flour Tinctures Quick Cannabis Glycerite Long-Simmering Ganja Glycerin Green Avenger Cannabis Tincture CHAPTER 2: Irie Appetizers Roasted Ganja Garlic Cannellini Dip Hookah Lounge Hummus Green Leafy Kale Salad in Brown Cannabutter Vinaigrette Obama’S Sativa Samosas Stuffed Stoned JalapeñO Poppers Sativa Shrimp Spring Rolls with Mango Sauce Ganja Guacamole Mini Kind Veggie Burritos Pico de Ganja and Nachos Kind Bud Bruschetta with Pot Pesto Stoner Celebrity Favorite: Lil’ Snoop Hot Doggy Doggs CHAPTER 3: Munchie Meals Reggae Rice and Bean Soup Cream of Sinsemilla Soup Tom Yum Ganja Stoner Celebrity Favorite: Texas Cannabis Chili Shroomin’ Broccoli Casserole Om Circle Stuffed Butternut Squash Chicken and Andouille Ganja Gumbo Time-Warp Tamales Red, Green, and Gold Rasta Pasta Potato Gnocchi with Wild Mushroom Ragu Big Easy Eggplant Alfredo Ganja Granny’s Smoked Mac ‘n’ Cheese Psychedelic Spanakopita Sour Diesel Pot Pie Cheeto Fried Chicken Bacon-Wrapped Pork Tenderloin with Mango Chipotle Glaze Pot-and-Pancetta-Stuffed Beef Tenderloin with Port Mushrooms CHAPTER 4: High Holidays Valentine’s Day, February 14: Sexy Ganja–Dipped Strawberries St. Patrick’s Day, March 17: Green Ganja Garlic Smashed Potatoes 4/20, Cannabis Day, April 20: 420 Farmers’ Market Risotto Independence Day, July 4: Sweet and Tangy Bar–B–Cannabis -

Medicinal Cannabis in the Netherlands: Most Patients Prefer Coffeeshop Over Pharmacy by Derrick Bergman (Encod, VOC)

Medicinal cannabis in the Netherlands: most patients prefer coffeeshop over pharmacy by Derrick Bergman (Encod, VOC) Medicinal cannabis has been legally available in Dutch pharmacies since 2003. But patients still face a lot of hurdles and problems to get -and keep- access to their medicine. In his book 'Medicinal Weed Oil: the ideal folk medicine', Dutch cannabis pioneer Wernard Bruining writes about a morning about twenty years ago. Bruining opened up the first cannabis coffeeshop in Amsterdam in 1973 and founded Europe's first growshop Positronics in 1985. He writes: “On a morning in 1994 I woke up with a little sentence in my head that kept coming back to me: 'Mediwiet en anders niet!'” This would translate as 'Medical Weed and nothing else!' Wernard continues: “I understood that I had to introduce the new word “MEDIWIET” in the Dutch language to broaden the image people have of cannabis and to reduce their focus on recreational use by pointing out other positive possibilities of this miraculous plant.” Wernard designed a “Mediwiet” logo with a big cannabis leaf and two Staffs of Asclepius, symbolizing the double benefit of cannabis, both on mind and body. He approached a number of cannabis coffeeshops and asked them to sell cannabis to medicinal users for half of their normal price. Within weeks fifty coffeeshops had agreed to do this. Wernard sent them posters with the text “Official Mediwiet Dealer”. Around the same time, a man called Ger de Zwaan started a foundation for medicinal cannabis in Rotterdam. Having went through the whole pharmaceutical circus himself, without any results apart from severe side effects, he had discovered cannabis and made a quite unbelievable recovery. -

Marijuana & Ohio Past, Present, Potential

MARIJUANA & OHIO PAST, PRESENT, POTENTIAL A research-based public policy review and discussion presented by the Marijuana Policies of Ohio Taskforce Joe Deters, Chair June 2015 Table of Contents Chair’s Letter . 2 Executive Summary . 3 Impact on Ohio’s Economy . 35 Impact on Public Safety . 53 Consequences of Marijuana Possession Offenses . 69 Impact on Individual and Public Health . 81 Appendix A: Bibliography . 147 Appendix B: The Economic Model Used . 166 Appendix C: Taskforce Members . 179 MARIJUANA POLICIES OF OHIO TASKFORCE 1 My Fellow Ohioans, Our nation’s laws, perceptions and opinions about marijuana are evolving rapidly . After spending much of the 20th Century imposing ever-stricter prohibitions on marijuana, America has recently taken a second look at the impacts of marijuana use, its potential as a medicine, and the tangible tradeoffs and costs that criminalizing its possession has had on our communities . This reevaluation has pushed the national conversation about marijuana, broadly, in one direction: toward a less restrictive, less criminalized stance . This conversation is taking place in every state, and true to the genius of our Constitution, different states are trying to find approaches to marijuana law that most appropriately reflect the opinions, beliefs, and needs of their citizens . The question of changing Ohio’s approach to marijuana policy may soon be put before voters – most likely on the November 2015 ballot . The rapid pace of change in marijuana policy across the country, however, has made it difficult to keep up with the experiences, research, and practices occurring in different states . Political arguments from all sides of this debate have made it even more challenging to separate fact from opinion .