Blunts and Blowt Jes: Cannabis Use Practices in Two Cultural Settings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 5: Smoking Regulations for Food Service Establishments

Section 5: Smoking Regulations Statement of Purpose Whereas there exists conclusive evidence that tobacco smoke causes cancer, respiratory and cardiac diseases, negative birth outcomes, irritations to the eyes, nose and throat; and whereas more than eighty percent of all smokers begin smoking before the age of eighteen years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Youth Surveillance - United States 2000," 50 MMWR 1(Nov. 2000); and whereas nationally in 2000, sixty nine percent of middle school age children who smoke at least once a month were not asked to show proof of age when purchasing cigarettes (Id.); and whereas the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has concluded that nicotine is as addictive as cocaine or heroin; and whereas the Institute of Medicine (IOM) concludes that raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products to 21 will reduce tobacco initiation, particularly among adolescents 15 – 17, and will improve health across the lifespan and save lives; and whereas sales of flavored little cigars increased by 23% between 2008 and 2010 and many non-cigarette tobacco products, such as cigars and cigarillos, can be sold in a single “dose;” enjoy a relatively low tax as compared to cigarettes; are available in fruit, candy and alcohol flavors; and are popular among youth; and whereas the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Surgeon General have stated that flavored tobacco products are considered to be “starter” products that help establish smoking habits that can lead to long-term addiction; and whereas despite state laws prohibiting the sale of tobacco products to minors, access by minors to tobacco products is a major problem; and whereas the sale of tobacco products is incompatible with the mission of health care institutions because it is detrimental to the public health and undermines efforts to educate patients on the safe and effective use of medication; now, therefore it is the intention of the Wareham Board of Health to regulate the access of tobacco products. -

Cannabis (Sub)Culture, the Subcultural Repository, and Networked Mediation

SIMULATED SESSIONS: CANNABIS (SUB)CULTURE, THE SUBCULTURAL REPOSITORY, AND NETWORKED MEDIATION Nathan J. Micinski A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2014 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Rob Sloane © 2014 Nathan Micinski All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor Subcultural theory is traditionally rooted in notions of social deviance or resistance. The criteria for determining who or what qualifies as subcultures, and the most effective ways to study them, are based on these assumptions. This project seeks to address these traditional modes of studying subcultures and discover ways in which their modification may lead to new understandings and ways of studying subcultures in the contemporary moment. This will be done by suggesting a change in the criteria of examining subcultures from that of deviance or resistance to identification with a collection of images, symbols, rituals, and narratives. The importance of this distinction is the ability to utilize the insights that studying subcultures can offer while avoiding the faults inherent in speaking for or at a subculture rather than with or from it. Beyond addressing theoretical concerns, this thesis aims to apply notions of subcultural theory to study the online community of Reddit, in particular, a subset known as r/trees–a virtual repository for those images, symbols, rituals, and narratives of cannabis subculture. R/trees illustrates the life and vibrancy of a unique subcultural entity, which to this point has evaded a cultural studies analysis. To that end, this project advocates for the importance of the cultural studies approach to analyzing cannabis subculture and further, to insert the findings of this study into that gap in the literature. -

Consumer Education

CONSUMER EDUCATION Massachusetts General Laws Penalties for Possession or Possession with the Intent to Distribute • Consumers may not sell marijuana to any other individual • Marijuana is a class D controlled substance under the Massachusetts Controlled Substances Act - Mass. Gen. Laws. ch. 94C, § 31 Possession for Personal Use An adult may possess up to one ounce of marijuana; up to 5 grams of marijuana may be marijuana concentrate. Within a primary residence, an adult may possess up to 10 ounces of marijuana and any marijuana produced by marijuana plants cultivated on the premises. An adult who possesses more than one ounce of marijuana or marijuana products must secure the products with a lock. • Mass. Gen. Laws. ch. 94G, § 7 • Mass. Gen. Laws. ch. 94G § 13(b) Possession of more than one ounce of marijuana is punishable by a fine of $500 and/or imprisonment of up to 6 months. However, first offenders of the controlled substances act will be placed on probation and all official records relating to the conviction will be sealed upon successful completion of probation. Subsequent offenses may result in a fine of $2000 and/or imprisonment of up to 2 years. Individuals previously convicted of felonies under the controlled substances act who are arrested with over an ounce of marijuana may be subject to a fine of $2000 and/or up to 2 years of imprisonment. • Mass. Gen. Laws. ch. 94C, § 34 Possession with Intent to Distribute For first offenders, possessing less than 50 pounds of marijuana with the intent to manufacture, distribute, dispense or cultivate is punishable by a fine of $500-$5,000 and/or imprisonment of up to 2 years. -

Other Tobacco Products (OTP) Are Products Including Smokeless and “Non-Cigarette” Materials

Other tobacco products (OTP) are products including smokeless and “non-cigarette” materials. For more information on smoking and how to quit using tobacco products, check out our page on tobacco. A tobacco user may actually absorb more nicotine from chewing tobacco or snuff than they do from a cigarette (Mayo Clinic). The health consequences of smokeless tobacco use include oral, throat and pancreatic cancer, tooth loss, gum disease and increased risk of heart disease, heart attack and stroke. (American Cancer Society, “Smokeless Tobacco” 2010) Smokeless tobacco products contain at least 28 cancer-causing agents. The risk of certain types of cancer increases with smokeless tobacco: Esophageal cancer, oral cancer (cancer of the mouth, throat, cheek, gums, lips, tongue). Other Tobacco Products (OTP) Include: Chewing/Spit Tobacco A smokeless tobacco product consumed by placing a portion of the tobacco between the cheek and gum or upper lip teeth and chewing. Must be manually crushed with the teeth to release flavor and nicotine. Spitting is required to get rid of the unwanted juices. Loose Tobacco Loose (pipe) tobacco is made of cured and dried leaves; often a mix of various types of leaves (including spiced leaves), with sweeteners and flavorings added to create an "aromatic" flavor. The tobacco used resembles cigarette tobacco, but is more moist and cut more coarsely. Pipe smoke is usually held in the mouth and then exhaled without inhaling into the lungs. Blunt Wraps Blunt wraps are hollowed out tobacco leaf to be filled by the consumer with tobacco (or other drugs) and comes in different flavors. Flavors are added to create aromas and flavors. -

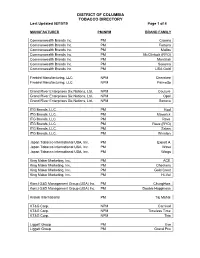

DISTRICT of COLUMBIA TOBACCO DIRECTORY Last Updated 08/15/19 Page 1 of 4

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TOBACCO DIRECTORY Last Updated 08/15/19 Page 1 of 4 MANUFACTURER PM/NPM BRAND FAMILY Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM Crowns Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM Fortuna Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM Malibu Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM McClintock (RYO) Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM Montclair Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM Sonoma Commonwealth Brands Inc. PM USA Gold Firebird Manufacturing, LLC NPM Cherokee Firebird Manufacturing, LLC NPM Palmetto Grand River Enterprises Six Nations, Ltd. NPM Couture Grand River Enterprises Six Nations, Ltd. NPM Opal Grand River Enterprises Six Nations, Ltd. NPM Seneca ITG Brands, LLC. PM Kool ITG Brands. LLC. PM Maverick ITG Brands, LLC. PM Rave ITG Brands, LLC. PM Rave (RYO) ITG Brands, LLC. PM Salem ITG Brands, LLC. PM Winston Japan Tobacco International USA, Inc. PM Export A Japan Tobacco International USA, Inc. PM Wave Japan Tobacco International USA, Inc. PM Wings King Maker Marketing, Inc. PM ACE King Maker Marketing, Inc. PM Checkers King Maker Marketing, Inc. PM Gold Crest King Maker Marketing, Inc. PM Hi-Val Konci G&D Management Group (USA) Inc. PM ChungHwa Konci G&D Management Group (USA) Inc. PM Double Happiness Kretek International PM Taj Mahal KT&G Corp. NPM Carnival KT&G Corp. NPM Timeless Time KT&G Corp. NPM This Liggett Group PM Eve Liggett Group PM Grand Prix DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TOBACCO DIRECTORY Last Updated 08/15/19 Page 2 of 4 MANUFACTURER PM/NPM BRAND FAMILY Liggett Group PM Liggett Select Liggett Group PM Montego Liggett Group PM Pyramid NASCO PM Red Sun NASCO PM SF Ohserase Manufacturing LLC NPM Signal Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM Amsterdam Shag (RYO) Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM Danish Export (RYO) Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM London Export (RYO) Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM Norwegian Shag (RYO) Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM Stockholm Blend (RYO) Peter Stokkebye Tobaksfabrik A/S PM Turkish Export (RYO) Philip Morris USA Inc. -

The Green Regulatory Arbitrage

Table of Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 1 II. PROHIBITION - HOW CANNABIS BECAME ILLEGAL ..................................................... 4 III. THE LEGAL LANDSCAPE .................................................................................................... 7 A. Federal Law And Its Impact On The Cannabis Industry ..................................................... 7 1. Cannabis Is A Schedule 1 Substance ............................................................................ 7 2. Access To Capital Markets Restricted ......................................................................... 9 3. Banking Services Limited .......................................................................................... 10 4. Tax Burdens .............................................................................................................. 11 5. Interstate And International Commerce Restrictions ................................................. 11 6. Insurance Options Limited ........................................................................................ 12 7. Medical Research And Clinical Trials Stymied .......................................................... 12 8. Professional Services Harder To Find ........................................................................ 13 9. Real Estate Challenges .............................................................................................. 13 B. The States -

Big-Catalogue-English-2020.Pdf

PAS CH SIO UT N D ® CATALOGUE English SEED COMPANY Feminized, autoflower and regular cannabis seeds AMSTERDAM, ESTABLISHED 1987 for recreational and medical use. Amsterdam - Maastricht YOUR PASSION OUR PASSION DUTCH PASSION 02 Contents Welcome to Dutch Passion Welcome to Dutch Passion 02 Dutch Passion was the second Cannabis Seed Company in the world, established in Amsterdam in 1987. It is our mission to supply Bestsellers 2019 02 the recreational and medical home grower with the highest quality cannabis products available in all countries where this is legally Regular, Feminized and Autoflower 03 allowed. Cannabinoids 03 Medical use of cannabis 03 After many years of dedication Dutch Passion remains a leading supplier of the world’s best cannabis genetics. Our experienced Super Sativa Seed Club 04 team do their utmost to maintain the quality of our existing varieties and constantly search for new ones from an extensive network Special Cannabinoids / THC-Victory 05 of worldwide sources. We supply thousands of retailers and seed distributors around the world. Dutch Outdoor 06 High Altitude 09 CBD Rich 10 Dutch Passion have never been afraid to upset conventional thinking; we invented feminized seeds in the 1990’s and more recently Latin America 13 have pioneered the introduction of 10-week Autoflower seeds which have helped make life even easier for the self-sufficient Classics 14 cannabis grower. CBD-rich medical cannabis genetics is a new area that we are proud to be leading. Skunk Family 19 Orange Family 21 The foundation of our success is the genetic control we have over our strains and the constant influx of new genetics that we obtain Blue Family 24 worldwide. -

TOBACCO WORLD RETAIL PRICES (Ovor 5,000 Retail PI-ICM)

THE CIGAR AND THE TOBACCO WORLD THE POPULAR JOURNAL TOBACCO OVER 40 YEARS OF TRADE USEFULNESS WORLD The Subscription includes : TOBACCO WORLD RETAIL PRICES (Ovor 5,000 Retail PI-ICM). RETAIL PRICES THE TOBACCO WORLD ANNUAL (Containing a word of Trad* Brand*—with Nam* and Addrau In each cms*). Membership of: TOBACCO WORLD SERVICE JUNE 1935 (With Pott Fnta raplUa In all Trad* difficult!**). The Cigar & Tobacco World HIYWOOO A COMPANY LTD. Dmrr How*, Kin—U 3tr*M, Ontry Una, London, W.C1 trantfc OACM f Baadmur. •trmlnfhtn, Uteanar. ToWfTHM i OffUlfrunt, Phono, LonAon. •Phono I TomaU far M1J Published by THE CIGAR & TOBACCO WORLD HEYWOOD & CO., LTD. DRURY HOUSE, RUSSELL STREET, DRURY LANE, LONDON, W.C.2 Branch Offices: MANCHESTER, BIRMINGHAM, LEICESTER Talagrarm : "Organigram. Phono, London." Phono : Tampla Bar MZJ '' Inar) "TOBACCO WORLD" RETAIL PRICES 1935 Authorised retail prices of Tobaccos, Cigarettes, Fancy Goods, and Tobacconists' Sundries. ABDULLA & Co., Ltd. (\BDULD^ 173 New Bond Street, W.l. Telephone; Bishopsgnte 4815, Authorised Current Retail Prices. Turkish Cigarettes. Price per Box of 100 50 25 20 10 No. 5 14/6 7/4 3/8 — 1/6 No. 5 .. .. Rose Tipped .. 28/9 14/6 7/3 — 3/- No. 11 11/8 5/11 3/- - 1/3 No. II .. .. Gold Tipped .. 13/S 6/9 3/5 - No. 21 10/8 5/5 2/9 — 1/1 Turkish Coronet No. 1 7/6 3/9 1/10J 1/6 9d. No. "X" — 3/- 1/6 — — '.i^Sr*** •* "~)" "Salisbury" — 2/6 — 1/- 6d. Egyptian Cigarettes. No. 14 Special 12/5 6/3 3/2 — — No. -

Marijuana Myths and Facts: the Truth Behind 10 Popular Misperceptions

MARIJUANA myths & FACTS The Truth Behind 10 Popular Misperceptions OFFICE OF NATIONAL DRUG CONTROL POLICY MARIJUANA myths & FACTS The Truth Behind 10 Popular Misperceptions OFFICE OF NATIONAL DRUG CONTROL POLICY TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.............................................................................. 1 Myth #1: Marijuana is harmless .......................................... 3 Myth #2: Marijuana is not addictive ................................... 7 Myth #3: Marijuana is not as harmful to your health as tobacco............................................................. 9 Myth #4: Marijuana makes you mellow............................. 10 Myth #5: Marijuana is used to treat cancer and other diseases...................................................... 11 Myth #6: Marijuana is not as popular as MDMA (Ecstasy) or other drugs among teens today...................... 13 Myth #7: If I buy marijuana, I’m not hurting anyone else......................................................... 14 Myth #8: My kids won’t be exposed to marijuana ............. 17 Myth #9: There’s not much parents can do to stop their kids from experimenting with marijuana ........... 19 Myth #10: The government sends otherwise innocent people to prison for casual marijuana use......... 21 Conclusion .............................................................................. 23 Glossary.................................................................................. 25 References .............................................................................. -

Considering Marijuana Legalization

Research Report Considering Marijuana Legalization Insights for Vermont and Other Jurisdictions Jonathan P. Caulkins, Beau Kilmer, Mark A. R. Kleiman, Robert J. MacCoun, Gregory Midgette, Pat Oglesby, Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, Peter H. Reuter C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/rr864 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2015 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions.html. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Marijuana legalization is a controversial and multifaceted issue that is now the subject of seri- ous debate. In May 2014, Governor Peter Shumlin signed Act 155 (S. -

Pink Floyd Amsterdam Coffeeshop

Pink floyd amsterdam coffeeshop Review of Amsterdam coffeeshop Pink Floyd, including atmosphere, pictures, contact, address, feeling and tips for visitors. Pink Floyd was a powerhouse of a coffeeshop in the good old daze of Amsterdam's 90's and naughties! Dampkring 2 is one of my favorite coffeeshops in Amsterdam for many reasons. It's still the same shop, still called Pink Floyd, but with the Dampkring menu. Years ago, Pink Floyd Coffeeshop was considered by many to be one of the best in all of Amsterdam. And while the quality of the service and. 2 reviews of Pink Floyd - CLOSED "This is my favourite coffee shop in the Recommended Reviews for Pink Floyd Best of Yelp Amsterdam – Coffee & Tea. Pink Floyd Coffeeshop. likes · 83 talking about this · were here. 64 Mohamed al Mokled st. right after AWLAD RAGAB Mostafa Alnahas themed. sitting at pink floyd coffeeshop amsterdam smoking. Coffeeshop Amsterdam is the best coffee shop in Amsterdam to truly experience the dutch cannabis culture. Modern interior with extensive menu & great music! Online menus from Coffeeshop Pink Floyd in Amsterdam Netherlands. Pink Floyd was bang opposite our hotel. it was our 1st and last stop . Went to Amsterdam twice and both times my first stop was the Pink Floyd Coffeeshop! great coffeshop! pink floyd album artwork all over the walls. very friendly staff,knowledgable weed men. One of the musts in the Amsterdam coffeeshop scene. then try Pink Floyd's Ummagumma. lol or Zappa on low.. if Dekuil turned it up There really aren't any coffee shops in the Amsterdam centrum and fringe areas. -

Maine Coefficient of Conservatism

Coefficient of Coefficient of Scientific Name Common Name Nativity Conservatism Wetness Abies balsamea balsam fir native 3 0 Abies concolor white fir non‐native 0 Abutilon theophrasti velvetleaf non‐native 0 3 Acalypha rhomboidea common threeseed mercury native 2 3 Acer ginnala Amur maple non‐native 0 Acer negundo boxelder non‐native 0 0 Acer pensylvanicum striped maple native 5 3 Acer platanoides Norway maple non‐native 0 5 Acer pseudoplatanus sycamore maple non‐native 0 Acer rubrum red maple native 2 0 Acer saccharinum silver maple native 6 ‐3 Acer saccharum sugar maple native 5 3 Acer spicatum mountain maple native 6 3 Acer x freemanii red maple x silver maple native 2 0 Achillea millefolium common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. borealis common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. millefolium common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea ptarmica sneezeweed non‐native 0 3 Acinos arvensis basil thyme non‐native 0 Aconitum napellus Venus' chariot non‐native 0 Acorus americanus sweetflag native 6 ‐5 Acorus calamus calamus native 6 ‐5 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry native 7 5 Actaea racemosa black baneberry non‐native 0 Actaea rubra red baneberry native 7 3 Actinidia arguta tara vine non‐native 0 Adiantum aleuticum Aleutian maidenhair native 9 3 Adiantum pedatum northern maidenhair native 8 3 Adlumia fungosa allegheny vine native 7 Aegopodium podagraria bishop's goutweed non‐native 0 0 Coefficient of Coefficient of Scientific Name Common Name Nativity