Arctic Climate Feedbacks: Global Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drought and Ecosystem Carbon Cycling

Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 151 (2011) 765–773 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Agricultural and Forest Meteorology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/agrformet Review Drought and ecosystem carbon cycling M.K. van der Molen a,b,∗, A.J. Dolman a, P. Ciais c, T. Eglin c, N. Gobron d, B.E. Law e, P. Meir f, W. Peters b, O.L. Phillips g, M. Reichstein h, T. Chen a, S.C. Dekker i, M. Doubková j, M.A. Friedl k, M. Jung h, B.J.J.M. van den Hurk l, R.A.M. de Jeu a, B. Kruijt m, T. Ohta n, K.T. Rebel i, S. Plummer o, S.I. Seneviratne p, S. Sitch g, A.J. Teuling p,r, G.R. van der Werf a, G. Wang a a Department of Hydrology and Geo-Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Earth and Life Sciences, VU-University Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1085, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands b Meteorology and Air Quality Group, Wageningen University and Research Centre, P.O. box 47, 6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands c LSCE CEA-CNRS-UVSQ, Orme des Merisiers, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France d Institute for Environment and Sustainability, EC Joint Research Centre, TP 272, 2749 via E. Fermi, I-21027 Ispra, VA, Italy e College of Forestry, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-5752 USA f School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh, EH8 9XP Edinburgh, UK g School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK h Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, PO Box 100164, D-07701 Jena, Germany i Department of Environmental Sciences, Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University, PO Box 80115, 3508 TC Utrecht, The Netherlands j Institute of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Vienna University of Technology, Gusshausstraße 27-29, 1040 Vienna, Austria k Geography and Environment, Boston University, 675 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA 02215, USA l Department of Global Climate, Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, P.O. -

Assessing the Role of Carbon Dioxide Removal in Companies' Climate

Net Expectations Assessing the role of carbon dioxide removal in companies’ climate plans. Briefing by Greenpeace UK January 2021 ~ While a few companies plan to deliver CDR Executive in specific projects, many plan to simply purchase credits on carbon markets, summary which have been beset with integrity problems and dubious accounting, even where certified. To stabilise global temperatures at any level – whether 1.5˚C, 2˚C, 3˚C or 5˚C Limits and uncertainties – carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions must The IPCC warns that reliance on CDR is a major reach net zero at some point, because risk to humanity’s ability to achieve the Paris goals. of CO2’s long-term, cumulative effect. The uncertainties are not whether mechanisms to remove CO2 “work”: they all work in a laboratory According to the Intergovernmental at least. Rather, it is whether they can be delivered Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), at scale, with sufficient funding and regulation, to store CO2 over the long term without unacceptable limiting warming to 1.5˚C requires net- social and environmental impacts. zero CO2 to be reached by about 2050. To illustrate the need for regulation, the carbon A small proportion of emissions is likely to be dioxide captured by forests is highly dependent on unavoidable and must be offset by carbon dioxide their specific circumstances, including their removal (CDR), such as by tree-planting (afforestation/ species diversity, the prior land use, and future reforestation) or by technological approaches like risks to the forest (such as fires or pests). In some bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) cases, forests and BECCS can increase rather than or direct air carbon capture with storage (DACCS). -

Forestry As a Natural Climate Solution: the Positive Outcomes of Negative Carbon Emissions

PNW Pacific Northwest Research Station INSIDE Tracking Carbon Through Forests and Streams . 2 Mapping Carbon in Soil. .3 Alaska Land Carbon Project . .4 What’s Next in Carbon Cycle Research . 4 FINDINGS issue two hundred twenty-five / march 2020 “Science affects the way we think together.” Lewis Thomas Forestry as a Natural Climate Solution: The Positive Outcomes of Negative Carbon Emissions IN SUMMARY Forests are considered a natural solu- tion for mitigating climate change David D’A more because they absorb and store atmos- pheric carbon. With Alaska boasting 129 million acres of forest, this state can play a crucial role as a carbon sink for the United States. Until recently, the vol- ume of carbon stored in Alaska’s forests was unknown, as was their future car- bon sequestration capacity. In 2007, Congress passed the Energy Independence and Security Act that directed the Department of the Inte- rior to assess the stock and flow of carbon in all the lands and waters of the United States. In 2012, a team com- posed of researchers with the U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Forest Ser- vice, and the University of Alaska assessed how much carbon Alaska’s An unthinned, even-aged stand in southeast Alaska. New research on carbon sequestration in the region’s coastal temperate rainforests, and how this may change over the next 80 years, is helping land managers forests can sequester. evaluate tradeoffs among management options. The researchers concluded that ecosys- tems of Alaska could be a substantial “Stones have been known to move sunlight, water, and atmospheric carbon diox- carbon sink. -

C2G Evidence Brief: Carbon Dioxide Removal and Its Governance

Carnegie Climate EVIDENCE BRIEF Governance Initiative Carbon Dioxide Removal An initiative of and its Governance 2 March 2021 Summary This briefing summarises the latest evidence relating to Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) techniques and their governance. It describes a range of techniques currently under consideration, exploring their technical readiness, current research, applicable governance frameworks, and other socio-political considerations in section I. It also provides an overview of some generic CDR governance issues and the key instruments relevant for the governance of CDR in section II. About C2G The Carnegie Climate Governance Initiative (C2G) seeks to catalyse the creation of effective governance for climate-altering approaches, in particular for solar radiation modification (SRM) and large-scale carbon dioxide removal (CDR). In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reaffirmed that large-scale CDR is required in all pathways to limit global warming to 1.5°C with limited or no overshoot. Some scientists say SRM may also be needed to avoid that overshoot. C2G is impartial regarding the potential use of specific approaches, but not on the need for their governance - which includes multiple, diverse processes of learning, discussion and decision-making, involving all sectors of society. It is not C2G’s role to influence the outcome of these processes, but to raise awareness of the critical governance questions that underpin CDR and SRM. C2G’s mission will have been achieved once their governance is taken on board by governments and intergovernmental bodies, including awareness raising, knowledge generation, and facilitating collaboration. C2G has prepared several other briefs exploring various CDR and SRM technologies and associated issues. -

Principles for Thinking About Carbon Dioxide Removal in Just Climate Policy

ll Commentary Principles for Thinking about Carbon Dioxide Removal in Just Climate Policy David R. Morrow,1,* Michael S. Thompson,2 Angela Anderson,3 Maya Batres,4 Holly J. Buck,5 Kate Dooley,6 Oliver Geden,7,8 Arunabha Ghosh,9 Sean Low,10 Augustine Njamnshi,11 John Noel,€ 4 Olu´ fẹ́mi O. Ta´ ı´wo` ,12 Shuchi Talati,3 and Jennifer Wilcox13 1Institute for Carbon Removal Law and Policy, American University, Washington, DC, USA 2Carnegie Climate Governance Initiative, New York, NY, USA 3Union of Concerned Scientists, Washington, DC, USA 4Independent scholar, USA 5UCLA School of Law, Los Angeles, CA, USA 6Australian-German Climate and Energy College, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia 7German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, Germany 8International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria 9Council on Energy, Environment, and Water, New Delhi, India 10Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, Potsdam, Germany 11Pan-African Climate Justice Alliance, Nairobi, Kenya 12Department of Philosophy, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA 13Chemical Engineering Department, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, MA, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.07.015 Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) is rising up the climate-policy agenda. Four principles for thinking about its role in climate policy can help ensure that CDR supports the kind of robust, abatement-focused long-term climate strategy that is essential to fair and effective implementation. Carbon dioxide removal (CDR), some- agencies are wrestling with the chal- Different people and institutions will times called carbon removal or negative lenge of forming positions on CDR, have different expectations about long- emissions, is the practice of capturing including whether to support it at all term climate strategies. -

Carbon Cycling and Biosequestration Integrating Biology and Climate Through Systems Science March 2008 Workshop Report

Carbon Cycling and Biosequestration Integrating Biology and Climate through Systems Science March 2008 Workshop Report http://genomicsgtl.energy.gov/carboncycle/ ne of the most daunting challenges facing science in processes that drive the global carbon cycle, (2) achieve greater the 21st Century is to predict how Earth’s ecosystems integration of experimental biology and biogeochemical mod- will respond to global climate change. The global eling approaches, (3) assess the viability of potential carbon Ocarbon cycle plays a central role in regulating atmospheric biosequestration strategies, and (4) develop novel experimental carbon dioxide (CO2) levels and thus Earth’s climate, but our approaches to validate climate model predictions. basic understanding of the myriad tightly interlinked biologi- cal processes that drive the global carbon cycle remains lim- A Science Strategy for the Future ited. Whether terrestrial and ocean ecosystems will capture, Understanding and predicting processes of the global carbon store, or release carbon is highly dependent on how changing cycle will require bold new research approaches aimed at linking climate conditions affect processes performed by the organ- global-scale climate phenomena; biogeochemical processes of isms that form Earth’s biosphere. Advancing our knowledge ecosystems; and functional activities encoded in the genomes of of biological components of the global carbon cycle is crucial microbes, plants, and biological communities. This goal presents to predicting potential climate change impacts, assessing the a formidable challenge, but emerging systems biology research viability of climate change adaptation and mitigation strate- approaches provide new opportunities to bridge the knowledge gies, and informing relevant policy decisions. gap between molecular- and global-scale phenomena. -

The Need for Fast Near-Term Climate Mitigation to Slow Feedbacks and Tipping Points

The Need for Fast Near-Term Climate Mitigation to Slow Feedbacks and Tipping Points Critical Role of Short-lived Super Climate Pollutants in the Climate Emergency Background Note DRAFT: 27 September 2021 Institute for Governance Center for Human Rights and & Sustainable Development (IGSD) Environment (CHRE/CEDHA) Lead authors Durwood Zaelke, Romina Picolotti, Kristin Campbell, & Gabrielle Dreyfus Contributing authors Trina Thorbjornsen, Laura Bloomer, Blake Hite, Kiran Ghosh, & Daniel Taillant Acknowledgements We thank readers for comments that have allowed us to continue to update and improve this note. About the Institute for Governance & About the Center for Human Rights and Sustainable Development (IGSD) Environment (CHRE/CEDHA) IGSD’s mission is to promote just and Originally founded in 1999 in Argentina, the sustainable societies and to protect the Center for Human Rights and Environment environment by advancing the understanding, (CHRE or CEDHA by its Spanish acronym) development, and implementation of effective aims to build a more harmonious relationship and accountable systems of governance for between the environment and people. Its work sustainable development. centers on promoting greater access to justice and to guarantee human rights for victims of As part of its work, IGSD is pursuing “fast- environmental degradation, or due to the non- action” climate mitigation strategies that will sustainable management of natural resources, result in significant reductions of climate and to prevent future violations. To this end, emissions to limit temperature increase and other CHRE fosters the creation of public policy that climate impacts in the near-term. The focus is on promotes inclusive socially and environmentally strategies to reduce non-CO2 climate pollutants, sustainable development, through community protect sinks, and enhance urban albedo with participation, public interest litigation, smart surfaces, as a complement to cuts in CO2. -

Climate Intervention (July 2021)

State of the Science FACT SHEET Climate Intervention Climate Intervention (CI), also called climate engineering or geoengineering, refers to deliberate, large‐scale actions intended to counteract aspects of climate change. This Fact Sheet explains some of the fundamental principles and issues associated with CI (1). Why Might Climate Intervention Be Considered? The main driver of climate change over the past century has been anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), a greenhouse gas (GHG). Increasing emission rates have caused present‐day atmospheric CO2 to reach the highest value in over a million years based on studies of emissions of atmospheric CO2 and its accumulation in the atmosphere, ocean, and terrestrial biosphere. The increased emissions of other GHGs, such as methane, nitrous oxide and ozone, also contribute to anthropogenic climate change. The increased accumulation of GHGs has led to warming over much of the globe, to acidification of ocean surface waters (from CO2) (2), and to many other well‐documented climate impacts (3). As climate change continues, if the world does not make the desired greenhouse gas emissions reductions (4) such as those initiated by the Paris agreement (5), governments and other entities might turn to CI to counteract increasing climate change impacts. CI could potentially be implemented by consensus or unilaterally; either way, a thorough understanding of CI methods, and their associated uncertainties and unintended side effects is essential. Principal CI methods are divided into two How might CDR be accomplished? general categories (6) (see figure): Oceanic sequestration: Adding nutrients, such as iron, to “ferti‐ lize” the ocean enhances biological growth (e.g., phytoplank‐ Carbon dioxide removal (CDR): CDR is a process to remove ton), which removes CO2 from surface waters and leads to lower CO2 from the atmosphere for long‐term storage on land or atmospheric levels. -

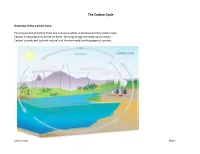

The Carbon Cycle

The Carbon Cycle Overview of the Carbon Cycle The movement of carbon from one area to another is the basis for the carbon cycle. Carbon is important for all life on Earth. All living things are made up of carbon. Carbon is produced by both natural and human-made (anthropogenic) sources. Carbon Cycle Page 1 Nature’s Carbon Sources Carbon is found in the Carbon is found in the lithosphere Carbon is found in the Carbon is found in the atmosphere mostly as carbon in the form of carbonate rocks. biosphere stored in plants and hydrosphere dissolved in ocean dioxide. Animal and plant Carbonate rocks came from trees. Plants use carbon dioxide water and lakes. respiration place carbon into ancient marine plankton that sunk from the atmosphere to make the atmosphere. When you to the bottom of the ocean the building blocks of food Carbon is used by many exhale, you are placing carbon hundreds of millions of years ago during photosynthesis. organisms to produce shells. dioxide into the atmosphere. that were then exposed to heat Marine plants use cabon for and pressure. photosynthesis. The organic matter that is produced Carbon is also found in fossil fuels, becomes food in the aquatic such as petroleum (crude oil), coal, ecosystem. and natural gas. Carbon is also found in soil from dead and decaying animals and animal waste. Carbon Cycle Page 2 Natural Carbon Releases into the Atmosphere Carbon is released into the atmosphere from both natural and man-made causes. Here are examples to how nature places carbon into the atmosphere. -

![Permafrost Carbon Feedbacks Threaten Global Climate Goals Downloaded by Guest on October 1, 2021 [EU] Member States Were Included in the EU’S Commitment)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2787/permafrost-carbon-feedbacks-threaten-global-climate-goals-downloaded-by-guest-on-october-1-2021-eu-member-states-were-included-in-the-eu-s-commitment-1262787.webp)

Permafrost Carbon Feedbacks Threaten Global Climate Goals Downloaded by Guest on October 1, 2021 [EU] Member States Were Included in the EU’S Commitment)

Permafrost carbon feedbacks threaten global BRIEF REPORT climate goals Susan M. Natalia,1, John P. Holdrenb, Brendan M. Rogersa, Rachael Treharnea, Philip B. Duffya, Rafe Pomerancea, and Erin MacDonalda aWoodwell Climate Research Center, Falmouth, MA 02540; and bBelfer Center for Science and International Affairs, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 Edited by Robert E. Dickinson, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, and approved March 9, 2021 (received for review January 5, 2021) Rapid Arctic warming has intensified northern wildfires and is wildfires (8, 9) that emit large amounts of carbon both directly thawing carbon-rich permafrost. Carbon emissions from perma- from combustion and indirectly by accelerating permafrost thaw. frost thaw and Arctic wildfires, which are not fully accounted for Fire-induced permafrost thaw and the subsequent decomposition in global emissions budgets, will greatly reduce the amount of of previously frozen organic matter may be a dominant source of greenhouse gases that humans can emit to remain below 1.5 °C Arctic carbon emissions during the coming decades (9). or 2 °C. The Paris Agreement provides ongoing opportunities to Despite the potential for a strong positive feedback from increase ambition to reduce society’s greenhouse gas emissions, permafrost carbon on global climate, permafrost carbon emissions which will also reduce emissions from thawing permafrost. In De- are not accounted for by most Earth system models (ESMs) or cember 2020, more than 70 countries announced more ambitious integrated assessment models (IAMs), including those that in- nationally determined contributions as part of their Paris Agree- formed the last assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel ment commitments; however, the carbon budgets that informed on Climate Change (IPCC) and the IAMs which informed the these commitments were incomplete, as they do not fully account IPCC’s special report on global warming of 1.5 °C (10, 11). -

Permafrost Soils and Carbon Cycling

SOIL, 1, 147–171, 2015 www.soil-journal.net/1/147/2015/ doi:10.5194/soil-1-147-2015 SOIL © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Permafrost soils and carbon cycling C. L. Ping1, J. D. Jastrow2, M. T. Jorgenson3, G. J. Michaelson1, and Y. L. Shur4 1Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, Palmer Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1509 South Georgeson Road, Palmer, AK 99645, USA 2Biosciences Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL 60439, USA 3Alaska Ecoscience, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA 4Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA Correspondence to: C. L. Ping ([email protected]) Received: 4 October 2014 – Published in SOIL Discuss.: 30 October 2014 Revised: – – Accepted: 24 December 2014 – Published: 5 February 2015 Abstract. Knowledge of soils in the permafrost region has advanced immensely in recent decades, despite the remoteness and inaccessibility of most of the region and the sampling limitations posed by the severe environ- ment. These efforts significantly increased estimates of the amount of organic carbon stored in permafrost-region soils and improved understanding of how pedogenic processes unique to permafrost environments built enor- mous organic carbon stocks during the Quaternary. This knowledge has also called attention to the importance of permafrost-affected soils to the global carbon cycle and the potential vulnerability of the region’s soil or- ganic carbon (SOC) stocks to changing climatic conditions. In this review, we briefly introduce the permafrost characteristics, ice structures, and cryopedogenic processes that shape the development of permafrost-affected soils, and discuss their effects on soil structures and on organic matter distributions within the soil profile. -

Accelerating Offshore Carbon Capture and Storage Opportunities and Challenges for CO2 Removal

Accelerating Offshore Carbon Capture and Storage Opportunities and Challenges for CO2 Removal Report on October 2020 Workshop 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary 2 Motivation 4 Background 5 Workshop Design 6 Essential Project Criteria 7 Workshop Process 8 Discussion Flow 8 Polling and Numerical Data 9 Data Summary and Observations 10 Average U Values by Criterion and Project Design 10 Specific Observations 11 Conclusions and Next Steps 11 Appendices 13 Appendix 1. Participant Biographies 14 Appendix 2. Workshop Agenda 23 Appendix 3. Major and Sub-Criteria for Each Project Design 24 Additional Readings 25 SUMMARY In October 2020, Columbia World Projects (CWP) held a 3-day workshop to discuss the challenge of scoping the uncertainties for offshore carbon dioxide (CO2) capture and mineralization. The workshop is a critical first step in moving potential new and essential technologies towards large-scale implementation. CWP was pleased to help participants envision how they could launch effective demonstration of field projects in the offshore environment. Climate change, caused by anthropogenic CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions, is one of the most urgent and extensive global threats confronting us today. The need to rapidly reduce emissions has prompted growing interest in CO2 capture and sequestration (CCS). However, there are many technical and non-technical challenges associated with implementing CCS technologies, particularly offshore. These include issues associated with long-term liabilities, various engineering and ecological concerns, as well as public acceptance. Workshop discussions focused on two potential offshore locations where designs for future demonstration projects are being considered. 1 Like other climate mitigation activities, offshore CCS poses a dynamic risk management problem.