Induced Ocean Acidification for Ocean in the East China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endoskeleton

THE EVOLUTION OF THE VERTEBRATE ENDOSKELETON AN ESSAY ON THE SIGNIFICANCE AND) MEANING OF' SEGMENTATION IN COELOMATE ANIMIALS By W1T. 13. PRIMIROSE, M.B.. Cii.B. Lately Seniior Deniionistrator of lAnatomtiy i? the (nWizversity (of Glasgozc THE EVOLUTION OF THE VERTEBRATE ENDOSKELETON WVHEN investigating the morphology of the vertebrate head, I found it necessary to discover the morphological principles on which the segmentation of the body is founded. This essay is one of the results of this investigations, and its object is to show what has determined the segmented form in vertebrate animals. It will be seen that the segmented form in vertebrates results from a condition which at no time occurs in vertebrate animals. This condition is a form of skeleton found only in animals lower in the scale of organisation than vertebrates, and has the characters of a space containing water. This space is the Coelomic Cavity. The coelomic cavity is the key to the formation of the segmented structure of the body, and is the structure that determines the vertebrate forni. The coclomic cavity is present in a well defined state from the Alnelida tuwards, so that in ainielides it is performing the functions for which a coelom was evolved. It is, however, necessary to observe the conditions prevailing anon)g still lower forms to see why a separate cavity was formed in animals, which became the means of raising them in the scale of organisation, and ultimately leading to the evolution of the vertebrate animal. I therefore propose to trace the steps in evolution by which, I presume, the coelomic cavity originated, and then show how it or its modifications have been the basis on which the whole vertebrate structure of animals is founded. -

Drought and Ecosystem Carbon Cycling

Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 151 (2011) 765–773 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Agricultural and Forest Meteorology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/agrformet Review Drought and ecosystem carbon cycling M.K. van der Molen a,b,∗, A.J. Dolman a, P. Ciais c, T. Eglin c, N. Gobron d, B.E. Law e, P. Meir f, W. Peters b, O.L. Phillips g, M. Reichstein h, T. Chen a, S.C. Dekker i, M. Doubková j, M.A. Friedl k, M. Jung h, B.J.J.M. van den Hurk l, R.A.M. de Jeu a, B. Kruijt m, T. Ohta n, K.T. Rebel i, S. Plummer o, S.I. Seneviratne p, S. Sitch g, A.J. Teuling p,r, G.R. van der Werf a, G. Wang a a Department of Hydrology and Geo-Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Earth and Life Sciences, VU-University Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1085, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands b Meteorology and Air Quality Group, Wageningen University and Research Centre, P.O. box 47, 6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands c LSCE CEA-CNRS-UVSQ, Orme des Merisiers, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France d Institute for Environment and Sustainability, EC Joint Research Centre, TP 272, 2749 via E. Fermi, I-21027 Ispra, VA, Italy e College of Forestry, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-5752 USA f School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh, EH8 9XP Edinburgh, UK g School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK h Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, PO Box 100164, D-07701 Jena, Germany i Department of Environmental Sciences, Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University, PO Box 80115, 3508 TC Utrecht, The Netherlands j Institute of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Vienna University of Technology, Gusshausstraße 27-29, 1040 Vienna, Austria k Geography and Environment, Boston University, 675 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA 02215, USA l Department of Global Climate, Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, P.O. -

Biology of Echinoderms

Echinoderms Branches on the Tree of Life Programs ECHINODERMS Written and photographed by David Denning and Bruce Russell Produced by BioMEDIA ASSOCIATES ©2005 - Running time 16 minutes. Order Toll Free (877) 661-5355 Order by FAX (843) 470-0237 The Phylum Echinodermata consists of about 6,000 living species, all of which are marine. This video program compares the five major classes of living echinoderms in terms of basic functional biology, evolution and ecology using living examples, animations and a few fossil species. Detailed micro- and macro- photography reveal special adaptations of echinoderms and their larval biology. (THUMBNAIL IMAGES IN THIS GUIDE ARE FROM THE VIDEO PROGRAM) Summary of the Program: Introduction - Characteristics of the Class Echinoidea phylum. spine adaptations, pedicellaria, Aristotle‘s lantern, sand dollars, urchin development, Class Asteroidea gastrulation, settlement skeleton, water vascular system, tube feet function, feeding, digestion, Class Holuthuroidea spawning, larval development, diversity symmetry, water vascular system, ossicles, defensive mechanisms, diversity, ecology Class Ophiuroidea regeneration, feeding, diversity Class Crinoidea – Topics ecology, diversity, fossil echinoderms © BioMEDIA ASSOCIATES (1 of 7) Echinoderms ... ... The characteristics that distinguish Phylum Echinodermata are: radial symmetry, internal skeleton, and water-vascular system. Echinoderms appear to be quite different than other ‘advanced’ animal phyla, having radial (spokes of a wheel) symmetry as adults, rather than bilateral (worm-like) symmetry as in other triploblastic (three cell-layer) animals. Viewers of this program will observe that echinoderm radial symmetry is secondary; echinoderms begin as bilateral free-swimming larvae and become radial at the time of metamorphosis. Also, in one echinoderm group, the sea cucumbers, partial bilateral symmetry is retained in the adult stages -- sea cucumbers are somewhat worm–like. -

Forestry As a Natural Climate Solution: the Positive Outcomes of Negative Carbon Emissions

PNW Pacific Northwest Research Station INSIDE Tracking Carbon Through Forests and Streams . 2 Mapping Carbon in Soil. .3 Alaska Land Carbon Project . .4 What’s Next in Carbon Cycle Research . 4 FINDINGS issue two hundred twenty-five / march 2020 “Science affects the way we think together.” Lewis Thomas Forestry as a Natural Climate Solution: The Positive Outcomes of Negative Carbon Emissions IN SUMMARY Forests are considered a natural solu- tion for mitigating climate change David D’A more because they absorb and store atmos- pheric carbon. With Alaska boasting 129 million acres of forest, this state can play a crucial role as a carbon sink for the United States. Until recently, the vol- ume of carbon stored in Alaska’s forests was unknown, as was their future car- bon sequestration capacity. In 2007, Congress passed the Energy Independence and Security Act that directed the Department of the Inte- rior to assess the stock and flow of carbon in all the lands and waters of the United States. In 2012, a team com- posed of researchers with the U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Forest Ser- vice, and the University of Alaska assessed how much carbon Alaska’s An unthinned, even-aged stand in southeast Alaska. New research on carbon sequestration in the region’s coastal temperate rainforests, and how this may change over the next 80 years, is helping land managers forests can sequester. evaluate tradeoffs among management options. The researchers concluded that ecosys- tems of Alaska could be a substantial “Stones have been known to move sunlight, water, and atmospheric carbon diox- carbon sink. -

Carbon Cycling and Biosequestration Integrating Biology and Climate Through Systems Science March 2008 Workshop Report

Carbon Cycling and Biosequestration Integrating Biology and Climate through Systems Science March 2008 Workshop Report http://genomicsgtl.energy.gov/carboncycle/ ne of the most daunting challenges facing science in processes that drive the global carbon cycle, (2) achieve greater the 21st Century is to predict how Earth’s ecosystems integration of experimental biology and biogeochemical mod- will respond to global climate change. The global eling approaches, (3) assess the viability of potential carbon Ocarbon cycle plays a central role in regulating atmospheric biosequestration strategies, and (4) develop novel experimental carbon dioxide (CO2) levels and thus Earth’s climate, but our approaches to validate climate model predictions. basic understanding of the myriad tightly interlinked biologi- cal processes that drive the global carbon cycle remains lim- A Science Strategy for the Future ited. Whether terrestrial and ocean ecosystems will capture, Understanding and predicting processes of the global carbon store, or release carbon is highly dependent on how changing cycle will require bold new research approaches aimed at linking climate conditions affect processes performed by the organ- global-scale climate phenomena; biogeochemical processes of isms that form Earth’s biosphere. Advancing our knowledge ecosystems; and functional activities encoded in the genomes of of biological components of the global carbon cycle is crucial microbes, plants, and biological communities. This goal presents to predicting potential climate change impacts, assessing the a formidable challenge, but emerging systems biology research viability of climate change adaptation and mitigation strate- approaches provide new opportunities to bridge the knowledge gies, and informing relevant policy decisions. gap between molecular- and global-scale phenomena. -

The Carbon Cycle

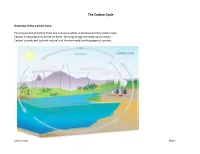

The Carbon Cycle Overview of the Carbon Cycle The movement of carbon from one area to another is the basis for the carbon cycle. Carbon is important for all life on Earth. All living things are made up of carbon. Carbon is produced by both natural and human-made (anthropogenic) sources. Carbon Cycle Page 1 Nature’s Carbon Sources Carbon is found in the Carbon is found in the lithosphere Carbon is found in the Carbon is found in the atmosphere mostly as carbon in the form of carbonate rocks. biosphere stored in plants and hydrosphere dissolved in ocean dioxide. Animal and plant Carbonate rocks came from trees. Plants use carbon dioxide water and lakes. respiration place carbon into ancient marine plankton that sunk from the atmosphere to make the atmosphere. When you to the bottom of the ocean the building blocks of food Carbon is used by many exhale, you are placing carbon hundreds of millions of years ago during photosynthesis. organisms to produce shells. dioxide into the atmosphere. that were then exposed to heat Marine plants use cabon for and pressure. photosynthesis. The organic matter that is produced Carbon is also found in fossil fuels, becomes food in the aquatic such as petroleum (crude oil), coal, ecosystem. and natural gas. Carbon is also found in soil from dead and decaying animals and animal waste. Carbon Cycle Page 2 Natural Carbon Releases into the Atmosphere Carbon is released into the atmosphere from both natural and man-made causes. Here are examples to how nature places carbon into the atmosphere. -

ZOOLOGY Zoology 109 (2006) 164–168

ARTICLE IN PRESS ZOOLOGY Zoology 109 (2006) 164–168 www.elsevier.de/zool Mineralized Cartilage in the skeleton of chondrichthyan fishes Mason N. Dean, Adam P. Summersà Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California – Irvine, 321 Steinhaus Hall, Irvine, CA 92697-2525, USA Received 10 February 2006; received in revised form 2 March 2006; accepted 3 March 2006 Abstract The cartilaginous endoskeleton of chondrichthyan fishes (sharks, rays, and chimaeras) exhibits complex arrangements and morphologies of calcified tissues that vary with age, species, feeding behavior, and location in the body. Understanding of the development, evolutionary history and function of these tissue types has been hampered by the lack of a unifying terminology. In order to facilitate reciprocal illumination between disparate fields with convergent interests, we present levels of organization in which crystal orientation/size delimits three calcification types (areolar, globular, and prismatic) that interact in two distinct skeletal types, vertebral and tessellated cartilage. The tessellated skeleton is composed of small blocks (tesserae) of calcified cartilage (both prismatic and globular) overlying a core of unmineralized cartilage, while vertebral cartilage usually contains all three types of calcification. r 2006 Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved. Keywords: Elasmobranch skeleton; Mineralization; Calcified cartilage; Tesserae Introduction (Summers, 2000; Schaefer and Summers, 2005; Dean et al., 2006) interests in cartilaginous skeletons, we need The breadth of morphological variation of the a common language. Furthermore, the current termi- mineralized cartilage of the endoskeleton of chon- nology masks unappreciated complexity in morphology drichthyan fishes (sharks, rays, and chimaeras) has led that will fuel future research in several of these fields. -

Permafrost Soils and Carbon Cycling

SOIL, 1, 147–171, 2015 www.soil-journal.net/1/147/2015/ doi:10.5194/soil-1-147-2015 SOIL © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Permafrost soils and carbon cycling C. L. Ping1, J. D. Jastrow2, M. T. Jorgenson3, G. J. Michaelson1, and Y. L. Shur4 1Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, Palmer Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1509 South Georgeson Road, Palmer, AK 99645, USA 2Biosciences Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL 60439, USA 3Alaska Ecoscience, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA 4Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA Correspondence to: C. L. Ping ([email protected]) Received: 4 October 2014 – Published in SOIL Discuss.: 30 October 2014 Revised: – – Accepted: 24 December 2014 – Published: 5 February 2015 Abstract. Knowledge of soils in the permafrost region has advanced immensely in recent decades, despite the remoteness and inaccessibility of most of the region and the sampling limitations posed by the severe environ- ment. These efforts significantly increased estimates of the amount of organic carbon stored in permafrost-region soils and improved understanding of how pedogenic processes unique to permafrost environments built enor- mous organic carbon stocks during the Quaternary. This knowledge has also called attention to the importance of permafrost-affected soils to the global carbon cycle and the potential vulnerability of the region’s soil or- ganic carbon (SOC) stocks to changing climatic conditions. In this review, we briefly introduce the permafrost characteristics, ice structures, and cryopedogenic processes that shape the development of permafrost-affected soils, and discuss their effects on soil structures and on organic matter distributions within the soil profile. -

Iron Biominerals: an Overview

IRON BIOMINERALS: AN OVERVIEW Richard B. Frankel Department of Physics California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 INTRODUCfION Biomineralization processes, by which organisms form inorganic minerals, are broadly distributed and occur in almost every phylum of the biological world 1,2,3. There is a large diversity of minerals formed, with over 60 currently known1. The cations of the most widely occuring minerals are the divalent alkaline earths Mg, Ca, Sr and Ba. These are paired with the anions carbonate, hydroxide, oxalate, oxide, phosphate, sulfate and sulfide. Silica, hydrous silicon oxide, also occurs widely in algae (fable 1). These minerals function as exo- and endoskeletons, cation storage, lenses, gravity devices and in other roles in various organisms. IRON BIOMINERALS Minerals of iron are also known to occur in many organisms. This is due perhaps, to the important role of iron in many metabolic processes, and to the difficulty for organisms posed by the toxic products of ferrous iron oxidation by 02 together with the insolubility of ferric iron at neutral pH. Formation of iron minerals allows organisms to accumulate iron for future metabolic needs while avoiding high intracellular concentrations of ferrous iron. Other attributes of iron biominerals that are potentially useful to organisms include hardness, density and magnetism. An important class of iron biominerals are the ferric hydroxides or oxy hydroxides, which occur as amorphous, colloidal precipiates, as quasi crystalline minerals such as ferrihydrite, or as crystalline minerals such as lepidocrocite or goethite (fable 2). Amorphous iron oxy-hydroxides are found in the sheaths and stalks produced by the so-called iron bacteria, Leptothrix and Galljanella, which utilize the oxidation of ferrous ions by 02 as a source of Table 1. -

Initial Stages of Calcium Uptake and Mineral Deposition in Sea Urchin Embryos

Initial stages of calcium uptake and mineral deposition in sea urchin embryos Netta Vidavskya, Sefi Addadib, Julia Mahamidc, Eyal Shimonid, David Ben-Ezrae, Muki Shpigele, Steve Weinera, and Lia Addadia,1 aDepartment of Structural Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel; bB-nano Ltd., Rehovot 76326, Israel; cDepartment of Molecular Structural Biology, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, 82152 Martinsried, Germany; dDepartment of Chemical Research Support, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel; and eIsrael Oceanographic and Limnological Research, National Center for Mariculture, Eilat 88112, Israel Edited by Patricia M. Dove, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, and approved October 31, 2013 (received for review July 10, 2013) Sea urchin larvae have an endoskeleton consisting of two calcitic fluorescent signal at the spicule tip (13). The dynamics of spicule spicules. We reconstructed various stages of the formation elongation also was studied in vivo by using calcein, which la- pathway of calcium carbonate from calcium ions in sea water to beled the surface of newly formed spicule areas (7, 14). Blocking mineral deposition and integration into the forming spicules. or interfering with calcium uptake by the cells, both in vivo and Monitoring calcium uptake with the fluorescent dye calcein shows in PMC cultures, shows that for the spicule to be formed, cal- that calcium ions first penetrate the embryo and later are de- cium first has to penetrate the cells (15–17). The manner in posited intracellularly. Surprisingly, calcium carbonate deposits are which calcium is transported to the PMCs is not known (7). It is distributed widely all over the embryo, including in the primary known that the ectoderm cells take part in spicule mineraliza- mesenchyme cells and in the surface epithelial cells. -

Molecular Mechanisms of Biomineralization in Marine Invertebrates Melody S

© 2020. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2020) 223, jeb206961. doi:10.1242/jeb.206961 REVIEW Molecular mechanisms of biomineralization in marine invertebrates Melody S. Clark* ABSTRACT biodiversity (Box 1). They are also important in global carbon Much recent marine research has been directed towards cycling. For example, our recent geological history has seen the ’ understanding the effects of anthropogenic-induced environmental world s oceans become a significant net sink of anthropogenic CO2, ’ change on marine biodiversity, particularly for those animals with with the estimation that the world s continental shelves (see −1 heavily calcified exoskeletons, such as corals, molluscs and urchins. Glossary) alone absorb 0.4 Pg carbon year (see Glossary) This is because life in our oceans is becoming more challenging for (known as blue carbon) (Bauer et al., 2013). The process whereby these animals with changes in temperature, pH and salinity. In the our oceans absorb CO2 is an important buffer for future increases in future, it will be more energetically expensive to make marine atmospheric CO2 and therefore an important weapon in global skeletons and the increasingly corrosive conditions in seawater are resilience to anthropogenic climate change. Previous estimates of expected to result in the dissolution of these external skeletons. blue carbon have concentrated on calculating the carbon assimilated However, initial predictions of wide-scale sensitivity are changing as by microscopic biomineralizers that live in the water column, such we understand more about the mechanisms underpinning skeletal as the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi (Balch et al., 2007). production (biomineralization). These studies demonstrate the However, there is increasing recognition that the invertebrate complexity of calcification pathways and the cellular responses of macrofauna, such as echinoderms and coralline algae, play animals to these altered conditions. -

The Carbon Cycle and Climate Change/J Bret Bennington – First Edition ISBN 1 3: 978-0-495-73855-8;;, ISBN 1 0: 0-495-73855-7

38557_00_cover.qxd 12/24/08 4:36 PM Page 1 The collection of chemical pathways by which carbon moves between Earth systems is called the carbon cycle and it is the flow of carbon through this cycle that ties together the functioning of the Earth’s atmosphere, biosphere, geosphere, and oceans to regulate the climate of our planet. This means that as drivers of planet Earth, anything we do to change the function or state of one Earth system will change the function and state of all Earth systems. If we change the composition of the atmosphere, we will also cause changes to propagate through the biosphere, hydrosphere, and geosphere, altering our planet in ways that will likely not be beneficial to human welfare. Understanding the functioning of the carbon cycle in detail so that we can predict the effects of human activities on the Earth and its climate is one of the most important scientific challenges of the 21st century. Package this module with any Cengage Learning text where learning about the car- bon cycle and humanity’s impact on the environment is important. About the Author Dr. J Bret Bennington grew up on Long Island and studied geology as an under- graduate at the University of Rochester in upstate New York. He earned his doctorate in Paleontology from the Department of Geological Sciences at Virginia Tech in 1995 and has been on the faculty of the Department of Geology at Hofstra University since 1993. Dr. Bennington’s research is focused on quantifying stability and change in marine benthic paleocommunities in the fossil record and on integrating paleontological and sedimentological data to understand the development of depositional sequences in both Carboniferous and Cretaceous marine environments.