The Nonstatutory Labor Exemption and the Conspiracy Between the NHL and OHL in NHLPA V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nfl Anti-Tampering Policy

NFL ANTI-TAMPERING POLICY TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1. DEFINITION ............................................................................... 2 Section 2. PURPOSE .................................................................................... 2 Section 3. PLAYERS ................................................................................. 2-8 College Players ......................................................................................... 2 NFL Players ........................................................................................... 2-8 Section 4. NON-PLAYERS ...................................................................... 8-18 Playing Season Restriction ..................................................................... 8-9 No Consideration Between Clubs ............................................................... 9 Right to Offset/Disputes ............................................................................ 9 Contact with New Club/Reasonableness ..................................................... 9 Employee’s Resignation/Retirement ..................................................... 9-10 Protocol .................................................................................................. 10 Permission to Discuss and Sign ............................................................... 10 Head Coaches ..................................................................................... 10-11 Assistant Coaches .............................................................................. -

Developing a Metric to Evaluate the Performances of NFL Franchises In

Developing a Metric to Evaluate the Performance of NFL Franchises in Free Agency Sampath Duddu, William Wu, Austin Macdonald, Rohan Konnur University of California - Berkeley Abstract This research creates and offers a new metric called Free Agency Rating (FAR) that evaluates and compares franchises in the National Football League (NFL). FAR is a measure of how good a franchise is at signing unrestricted free agents relative to their talent level in the offseason. This is done by collecting and combining free agent and salary information from Spotrac and player overall ratings from Madden over the last six years. This research allowed us to validate our assumptions about which franchises are better in free agency, as we could compare them side to side. It also helped us understand whether certain factors that we assumed drove free agent success actually do. In the future, this research will help teams develop better strategies and help fans and analysts better project where free agents might go. The results of this research show that the single most significant factor of free agency success is a franchise’s winning culture. Meanwhile, factors like market size and weather, do not correlate to a significant degree with FAR, like we might anticipate. 1 Motivation NFL front offices are always looking to build balanced and complete rosters and prepare their team for success, but often times, that can’t be done without succeeding in free agency and adding talented veteran players at the right value. This research will help teams gain a better understanding of how they compare with other franchises, when it comes to signing unrestricted free agents. -

2021 Nfl Free Agency Questions & Answers

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 3/15/21 http://twitter.com/nfl345 2021 NFL FREE AGENCY QUESTIONS & ANSWERS SALARY CAP SET AT $182.5 MILLION Q. When does the 2021 free agency signing period begin? A. At 4:00 p.m. ET on Wednesday, March 17. Q. When is the two-day negotiating period for potential unrestricted free agents? A. From 12:00 p.m. ET on Monday, March 15 until 3:59:59 p.m. ET on Wednesday, March 17, clubs are permitted to contact and enter into contract negotiations with the certified agents of players who will become unrestricted free agents upon expiration of their 2020 player contracts at 4:00 p.m. ET on March 17. Q. What are the categories of free agency? A. Players are either “restricted free agents” or “unrestricted free agents.” A restricted free agent may be subject to a “qualifying offer.” A restricted or unrestricted free agent may be designated by his prior club as its franchise player or transition player. Q. What is the time period for free agency signings this year? A. For restricted free agents, from March 17 to April 23. For unrestricted free agents who have received a tender from their prior club by the Monday immediately following the final day of the NFL Draft for the 2021 League Year (i.e., May 3), from March 17 to July 22 (or the first scheduled day of the first NFL training camp, whichever is later). For franchise players, from March 17 until the Tuesday following Week 10 of the regular season, November 16. -

Official Alumni News of the Kitchener Rangers Spring 2019 Edition

OFFICIAL ALUMNI NEWS OF THE KITCHENER RANGERS SPRING 2019 EDITION FORMER COACH AND GENERAL MANAGER focuses on as he helps his team navigate You are focused on your individual teams. OF THE KITCHENER RANGERS AND their way through the playoffs. “I think the But yes, you do take a lot of pride in seeing CURRENT ASSISTANT COACH OF THE level of stress in the playoffs goes up for them succeed and obviously love seeing us as coaches. I don’t think you coach too players do well as they were a big part SAN JOSE SHARKS, STEVE SPOTT, WEIGHS differently, but the one area we pay more of our team here in Kitchener.” Looking IN ON HIS PLAYOFF EXPERIENCE AND HIS attention to is making sure you have the back on his time here in KW, Steve can’t TIME IN THE NHL. right people on the ice at the right time,” help but reminisce about the Rangers’ — said Steve. Memorial Cup victory in 2003. It was Steve describes the NHL as having three moments like this one that has helped seasons—the preseason, the regular “When you play against some of the prepare him for as some call it, ‘the show.’ season and the playoffs. Each season best players in the world you have to brings new experiences and requires try and negate their opportunity to “Winning the Memorial Cup with Kitchener players and coaches to shift and adjust score by matching your team up has definitely prepared me for this,” their game and coaching style. against the right players.” said Steve. -

2021 Nhl Awards Presented by Bridgestone Information Guide

2021 NHL AWARDS PRESENTED BY BRIDGESTONE INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 NHL Award Winners and Finalists ................................................................................................................................. 3 Regular-Season Awards Art Ross Trophy ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................. 6 Calder Memorial Trophy ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Frank J. Selke Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Hart Memorial Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 18 Jack Adams Award .................................................................................................................................................. 24 James Norris Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................ 28 Jim Gregory General Manager of the Year Award ................................................................................................. -

2019 - 202O SEASON SCHOOL DAY NOVEMBER 14, 2019 | PRESENTED BY: Dear Students

2019 - 202O SEASON SCHOOL DAY NOVEMBER 14, 2019 | PRESENTED BY: Dear Students, The Icemen organization and I are thrilled to have you join us to share the excitement of our third season! Our organization is dedicated to becoming an integral part of our community. The Icemen are proud to be partnered with the National Hockey League and our NHL affiliate, the Winnipeg Jets. You will have the opportunity to watch, learn about, and cheer on future NHL stars that begin their journey to the big show, proudly wearing the Icemen crest. We will continue to introduce new and exciting promotional nights for all 36 regular season home games. We treat each game as a major entertainment event. Our goal remains to bring you the best from the moment you arrive to the time the final horn sounds. Our mission is for you to have fun enjoying the Icemen Experience. From the entire Icemen family, thank you for being here with us today for the third Annual School Day Hockey Game. We hope you enjoy the game and learn about the sport of hockey. Good luck and go Icemen! Bob Ohrablo Bob Ohrablo, President TABLE OF 1 Table of Contents 2 Hockey Vocabulary 3 Vocabulary Bingo 4 - 5 The Amazing Zamboni 6 Color Mixing 7 Jacksonville Hockey History Timeline 8 Shapes in Hockey 9 Word Problems 10 Statistics & Graphing 11 Hockey Science 12 Science Friction 13 Teamwork 14 Player’s Anatomy 15 Compare & Contrast 16 English 101 with Mad Libs 17 Game Recap with the 5Ws 18 - 19 Sportsmanship 20 Create-a-Jersey INTRO TO HOCKEY Check off the words as they occur in game. -

The Effects of Collective Bargaining on Minor League Baseball Players

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLS\4-1\HLS102.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-MAY-13 15:57 Touching Baseball’s Untouchables: The Effects of Collective Bargaining on Minor League Baseball Players Garrett R. Broshuis* Abstract Collective bargaining has significantly altered the landscape of labor relations in organized baseball. While its impact on the life of the major league player has garnered much discussion, its impact on the majority of professional baseball players—those toiling in the minor leagues—has re- ceived scant attention. Yet an examination of every collective bargaining agreement between players and owners since the original 1968 Basic Agree- ment reveals that collective bargaining has greatly impacted minor league players, even though the Major League Baseball Players Association does not represent them. While a few of the effects of collective bargaining on the minor league player have been positive, the last two agreements have estab- lished a dangerous trend in which the Players Association consciously con- cedes an issue with negative implications for minor leaguers in order to receive something positive for major leaguers. Armed with a court-awarded antitrust exemption solidified by legisla- tion, Major League Baseball has continually and systematically exploited mi- * Prior to law school, the author played six years as a pitcher in the San Francisco Giants’ minor league system and wrote about life in the minors for The Sporting News and Baseball America. He has represented players as an agent and is a J.D. Candidate, 2013, at Saint Louis University School of Law. The author would like to thank Professor Susan A. FitzGibbon, Director, William C. -

1982-83 O-Pee-Chee Hockey Set Checklist

1982-83 O-Pee-Chee Hockey Set Checklist 1 Wayne Gretzky Highlight 2 Mike Bossy Highlight 3 Dale Hawerchuk Highlight 4 Mikko Leinonen Highlight 5 Bryan Trottier Highlight 6 Rick Middleton Team Leader 7 Ray Bourque 8 Wayne Cashman 9 Bruce Crowder RC 10 Keith Crowder RC 11 Tom Fergus RC 12 Steve Kasper 13 Normand Leveille RC 14 Don Marcotte 15 Rick Middleton 16 Peter McNab 17 Mike O'Connell 18 Terry O'Reilly 19 Brad Park 20 Barry Pederson RC 21 Brad Palmer RC 22 Pete Peeters 23 Rogatien Vachon 24 Ray Bourque In Action 25 Gilbert Perreault Team Leader 26 Mike Foligno 27 Yvon Lambert 28 Dale McCourt 29 Tony McKegney 30 Gilbert Perreault 31 Lindy Ruff 32 Mike Ramsey 33 J.F. Sauve RC 34 Bob Sauve 35 Ric Seiling 36 John Van Boxmeer 37 John Van Boxmeer In Action 38 Lanny McDonald Team Leader 39 Mel Bridgman 40 Mel Bridgman In Action 41 Guy Chouinard 42 Steve Christoff Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Denis Cyr RC 44 Bill Clement 45 Richie Dunn 46 Don Edwards 47 Jamie Hislop 48 Steve Konroyd RC 49 Kevin LaVallee 50 Reggie Lemelin 51 Lanny McDonald 52 Lanny McDonald In Action 53 Bob Murdoch 54 Kent Nilsson 55 Jim Peplinski 56 Paul Reinhart 57 Doug Risebrough 58 Phil Russell 59 Howard Walker RC 60 Al Secord Team Leader 61 Murray Bannerman 62 Keith Brown 63 Doug Crossman RC 64 Tony Esposito 65 Greg Fox 66 Tim Higgins 67 Reg Kerr 68 Tom Lysiak 69 Grant Mulvey 70 Bob Murray 71 Rich Preston 72 Terry Ruskowski 73 Denis Savard 74 Al Secord 75 Glen Sharpley 76 Darryl Sutter 77 Doug Wilson 78 Doug Wilson In Action 79 John Ogrodnick Team Leader -

Ice Hockey Rules Comparison Chart

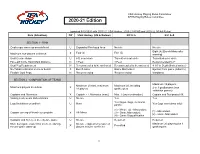

USA Hockey Playing Rules Committee NFHS Playing Rules Committee 2020-21 E (updated 9/10/2020 with 2017-21 USA Hockey, 2020-21 NFHS and 2020-22 NCAA Rules) Rule (Situation) Dif USA Hockey (HS & Below) N F H S N C A A SECTION 1 - RINK Goalkeeper warm-up area defined U Expanded Privileged Area No rule No rule Eight (8) [Bench Minor after X Four (4) Five (5) Maximum non-players on bench warning] Goal Crease shape U 6 ft. semi-circle Truncated semi-circle Truncated semi-circle Face-Off Circle Hash Mark Distance N 4 Feet 4 Feet Recommended 5’-7” Goal Peg Requirement N Recommended to be anchored Recommended to be anchored 8-10” in Depth (limited waiver) No Tobacco/Alcohol on ice or bench X Bench minor Game Misconduct Ejection from game (tobacco) Flexible Goal Pegs N Recommended Recommended Mandated SECTION 2 - COMPOSITION OF TEAMS Maximum 19 players; Maximum 20 total, maximum Maximum 20, including Maximum players in uniform X 18 players goalkeepers 2 or 3 goalkeepers (non- exhibition games) Captains and Alternates X Captain + 2 Alternates (max.) Max. 3 (any combination) Captain and Designated Alt. Visiting team wears dark uniforms U No rule Yes Yes Yes (logos, flags, memorial Logo limitations on uniform U None Yes (logo restrictions only) patch) (1) - Minor; (2) - Misconduct; (1) - Misconduct Captain coming off bench to complain X All- Minor (3) - Game Misconduct; (2) - Game Misconduct (4) - Game Disqualification Captains and Referees meet before game U No rule Required Required More than game roster limit on the ice during No rule - implied -

Team Canada's All-Time Records

TEAM CANADA’S ALL-TIME RECORDS WORLD JUNIOR CHAMPIONSHIP (1977 - 2006) FICHE DE TOUS LES TEMPS D’ÉQUIPE CANADA CHAMPIONNAT MONDIAL JUNIOR (1977 À 2006) RECORDS BY YEAR - CANADA ALL-TIME LEADING SCORERS MOST POINTS, FORWARD LINE FICHES PAR ANnéé - CANADA MEILLEURS POINTEURS DE TOUS LES TEMPS PLUS DE POINTS, PAR UN TRIO PLAYER GP G A PTS 69 Markus Naslund, Peter Forsberg, YEAR GP W L T GF GA POS JOUEUR PJ B A PTS Niklas Sundstrom (SWE) 1. Forsberg, Peter (SWE) 14 10 32 42 (30G/B, 39A/P) – 1993 in Sweden/en Suède ANNÉE PJ V D N BP PC Rang 52 Esa Keskinen, Mikko Makela, Esa Tikkanen (FIN) 2006 6 6 0 0 24 6 1st/1er 2. Reichel, Robert (TCH) 21 18 22 40 (24G/B, 28A/P) – 1985 in Finland/en Finlande 2005 6 6 0 0 41 7 1st/1er 3. Bure, Pavel (URS) 21 27 12 39 50 Robert Reichel, Jaromir Jagr, Bobby Holik (TCH) 2004 6 5 1 0 35 9 2nd/2e 4. Mogilny, Alexander (URS) 21 18 17 35 (22G/B, 28A/P) – 1990 in Finland/en Finlande e 5. Tikkanen, Esa (FIN) 21 17 18 35 47 Esa Keskinen, Raimo Helminen, Esa Tikkanen (FIN) 2003 6 5 1 0 26 11 2nd/2 (23G/B, 24A/P) – 1984 in Sweden/en Suède e 6. Ruzicka, Vladimir (TCH) 19 25 9 34 2002 7 5 2 0 40 14 2nd/2 7. Näslund, Markus (SWE) 14 21 13 34 46 Raimo Summanen, Petri Skriko, Risto Jalo (FIN) e 2001 7 4 2 1 26 16 3rd/3 8. -

Volume 25, Number 02, July 2003

ENTERTAINMENT LAW REPORTER WASHINGTON MONITOR FCC adopts new rules that generally permit companies to own more media businesses than they could before The Federal Communications Commission has adopted new media ownership rules, following a 20- month study it said was the “most comprehensive review of media ownership regulation in the agency’s history.” The new rules affect the ownership of four types of media businesses: (1) television networks; (2) television stations; (3) radio stations; and (4) daily newspapers that are owned by companies that also own radio or television stations. In general, the new rules allow companies to own more media businesses than they could before. For that reason, the new rules have been very controversial, VOLUME 25, NUMBER 2, JULY 2003 ENTERTAINMENT LAW REPORTER within Congress and elsewhere. Each of the new rules - there are six of them - is unique and complicated, and their significance can be understood only with some historical background. In the now-distant past, the FCC enforced a host of rules that limited, in many ways, the ownership of radio and television stations, cable systems and newspapers. The FCC itself abandoned some of those rules, like one that used to limit the number of television stations any one company could own in the top-50 markets (ELR 1:17:4). Other rules were eliminated or loosened by Congress; one of those limited the number of stations any one company could own, and it capped the maximum percentage of the national audience that any one broadcasting company could reach, a cap that Congress raised from 25% to 35% in the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (ELR 17:11:14). -

View Rulebook

We want to thank you for purchasing this set of player cards for Hockey Bones. We are very excited to continue to bring you our in-house produced cardsets. Many, many hours of work by many people went into getting the card generator program into a usable fashion that allows us to produce this and future sets. In addition, we will now be able to reintroduce past season card- sets. A task that was not possible with the old program. So let’s get to playing the fastest team sport in the world on your tabletop! Hockey Bones RememBeR if you Have any questions feel fRee to visit ouR foRums at www.spoRts.ptgamesinc.com For players of the original Faceoff Hockey some cosmetic changes to player cards have been made: For the 2013 sets and onward plus the retro seasons under the Hockey Bones name have re- worked the symbols. ONLY for those sets is the not below applicable otherwise, ignore the note below. The star has been replaced by the asterisk *for ace penalty killers. The up arrow ↑ has been replaced by the † for forechecking. For Goalie cards sets. * has been removed from all 2013 onward and 1970 onward Enjoy the set! Bench Minor/Game Misconduct Ratings for 1979-80 Team BM Rating GM Rating Atlanta 1-5(1) 1-10 Boston 1-5(4) 1-8 Buff alo 1-5(5) 1-4(5) Chicago 1-5(2) 1-8(4) Colorado 1-5(4) 1-7 Detroit 1-5(2) 1-10(2) Edmonton 1-5(1) 2-2(1) Hartford 1-5(2) 1-10(5) Los Angeles 1-5(2) 1-7(2) Minnesota 1-4(4) 1-8(3) Montreal 1-4(5) 1-9 New York I 1-3 1-6(4) New York R 1-4(4) 1-10(3) Philadelphia 1-7(4) 2-9(1) Pittsburgh 1-5(1) 2-8(5) Quebec 1-6(3) 1-9(4) St.