Volume 25, Number 02, July 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Alumni News of the Kitchener Rangers Spring 2019 Edition

OFFICIAL ALUMNI NEWS OF THE KITCHENER RANGERS SPRING 2019 EDITION FORMER COACH AND GENERAL MANAGER focuses on as he helps his team navigate You are focused on your individual teams. OF THE KITCHENER RANGERS AND their way through the playoffs. “I think the But yes, you do take a lot of pride in seeing CURRENT ASSISTANT COACH OF THE level of stress in the playoffs goes up for them succeed and obviously love seeing us as coaches. I don’t think you coach too players do well as they were a big part SAN JOSE SHARKS, STEVE SPOTT, WEIGHS differently, but the one area we pay more of our team here in Kitchener.” Looking IN ON HIS PLAYOFF EXPERIENCE AND HIS attention to is making sure you have the back on his time here in KW, Steve can’t TIME IN THE NHL. right people on the ice at the right time,” help but reminisce about the Rangers’ — said Steve. Memorial Cup victory in 2003. It was Steve describes the NHL as having three moments like this one that has helped seasons—the preseason, the regular “When you play against some of the prepare him for as some call it, ‘the show.’ season and the playoffs. Each season best players in the world you have to brings new experiences and requires try and negate their opportunity to “Winning the Memorial Cup with Kitchener players and coaches to shift and adjust score by matching your team up has definitely prepared me for this,” their game and coaching style. against the right players.” said Steve. -

Dallas Section1.Pdf

2009-2010 media guide STARS ORGANIZATION Top 10 Rankings . .187 Staff Directory . .2-5 Career Leaders . .188 American Airlines Center . .5-6 Single Season Leaders . .189 Dr Pepper StarCenters . .7 20-Goal Scorers . .190 Dr Pepper Arena . .8 Hat Tricks . .191-193 Texas Stars - Cedar Park Center . .9 Goaltenders Year-By-Year . .194-196 Thomas O. Hicks . .10 Shutouts . .197-201 Jeff Cogen . .11 Penalty Shots . .202 Hicks Holdings, LLC . .12 Special Teams . .203 Joe Nieuwendyk . .13 Overtime . .204-205 Les Jackson . .14 Shootout Results . .206 Frank Provenzano . .14 Best Record After… . .207 Brett Hull . .15 Individual Records vs. Opponents . .208 Dave Taylor . .15 Stanley Cup Champions . .208 Marc Crawford . .16 Seasonal Streaks . .209 Assistant Coaches . .17 All-Time Longest Streaks . .210 Senior Management . .18 Record By Month . .211-212 Scouting Staff . .19 Record By Day . .213-214 Training and Medical Staff . .20 Youngest and Oldest Stars . .215 Hockey Operations Staff . .21-23 Yearly Attendance . .215 Broadcasting . .24 The Last Time... .216 Communications Staff . .25 Regular Season Records . .217-222 Scoring and Results, Year-By-Year . .223-262 2009-2010 DALLAS STARS Administration . .263 Players . .26-84 Coaching Tenures . .263 In The System . .85-90 Coaching Records . .264 Future Stars . .91-93 All-Time Roster . .265-272 2009 Draft Selections . .94 All-Time Goaltenders . .273 All-Time Draft Selections . .95-98 Last Trade By Club . .274 Player Personnel . .99-100 Dallas Stars Trades . .275-278 Pronunciation Guide . .100 All-Time Jersey Numbers . .279-280 Texas Stars Information/Management . .101-102 National Awards . .281 Idaho Steelheads Directory/Schedule . .103 Retired Numbers . -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 6/12/2021 Arizona Coyotes Colorado Avalanche 1215584 Coyotes interview Stars assistant Todd Nelson for open 1215612 Positives to Avalanche’s season buried beneath the bitter HC job end 1215585 Coyotes to interview Blues assistant Mike Van Ryn for 1215613 For Avalanche, another Stanley Cup that got away head-coachinG job 1215614 Fine lines: Knights receive scoring help across all 4 units 1215615 Dater Column: Avalanche, like Sisyphus, Can’t Get Over Boston Bruins the Hump 1215586 With no contract and upcominG surGery, Tuukka Rask’s hockey future is uncertain but he only wants to play in B Columbus Blue Jackets 1215587 Bruins veteran David Krejci is doinG some deep thinking 1215616 'Nobody seemed to Get over the ‘Lars bar.' Why the Blue about his future Jackets chose Brad Larsen as new head coach 1215588 Tuukka Rask plans to have offseason hip surgery, and 1215617 Michael Arace: Maybe the Brad Larsen hire isn't as other news from the Bruins’ exit interviews uninspired and ambitionless as it looks 1215589 Bruins notebook: David Krejci’s future undecided 1215618 Blue Jackets were zeroed in on Brad Larsen from the start 1215590 Tuukka Rask has been playing with torn labrum, will have of the coaching search surGery 1215591 Conroy: BiG questions for Bruins’ offseason Detroit Red Wings 1215592 Coyle calls criticism Tuukka Rask deals with 'insane' 1215619 Here's where the Detroit Red WinGs' draft pick from the 1215593 Bruins star David Krejci can't see himself playinG for WashinGton Capitals falls different team 1215620 -

2011-12 WCHA Men's Season-In-Review

Western Collegiate Hockey Association Bruce M. McLeod Commissioner Carol LaBelle-Ehrhardt Assistant Commissioner of Operations Greg Shepherd Supervisor of Officials Administrative Office April 23, 2012 Western Collegiate Hockey Association 2211 S. Josephine Street, Room 302 Denver, CO 80210 2011-12 WCHA Men’s Season-in-Review p: 303 871-4491. f: 303 871-4770 Minnesota Reigns as Regular Season/MacNaughton Cup Champion; Gophers Win NCAA West [email protected] Regional to Represent WCHA at NCAA Men’s Frozen Four; North Dakota Captures Record Third Doug Spencer Straight WCHA Final Five Title and Broadmoor Trophy; UND, Minnesota Duluth, Denver Also Earn Associate Commissioner for Public Relations NCAA Tourney Bids But Fall Short at Regionals; UMD Forward Jack Connolly Named Hobey Baker Western Collegiate Hockey Association Memorial Award and Lowe’s Senior CLASS Winner; Seven WCHA Players Earn All-American Honors; 559 D’Onofrio Drive, Ste. 103 Madison, WI 53719-2096 DU Defenseman Joey LaLeggia Named National Rookie of the Year; UM’s Don Lucia, MTU’s Mel p: 608 829-0100. f: 608 829-0200 Pearson Named Finalists for Men’s Div. 1 National Coach of the Year; UMD’s Jack Connolly Named [email protected] WCHA Player of the Year, UND’s Brad Eidsness is Student-Athlete of the Year, MTU’s Mel Pearson Home of a Collegiate Record 37 is League’s Coach of the Year to Highlight Conference Awards for 2011-12; League Announces Men’s National Championship Record Numbers for WCHA Scholar-Athletes, All-WCHA Academic Team Honorees; Final Two Div. Teams Since 1951 1 Men’s Weekly National Polls Show UM at No. -

2016-17-OHL-Information-Guide.Pdf

CCM® IS A REGISTERED TRADEMARK OF SPORT MASKA INC. AND IS USED UNDER LICENSE BY REEBOK-CCM HOCKEY, U.S., INC. BE AHEAD OF THE GAME ONE PIECE SEAMLESS BOOT CONSTRUCTION THE NEW MONOFRAME 360 TECHNOLOGY IS ENGINEERED FAST. THIS UNPARALLELED ONE PIECE SEAMLESS BOOT CONSTRUCTION OFFERS A UNIQUE CLOSE FIT TO HELP MAXIMIZE DIRECT ENERGY TRANSFER. CCMHOCKEY.COM/SUPERTACKS 2016CCM_SuperTacks_Print_ads_OHL.indd 1 2016-08-02 10:25 CCM® IS A REGISTERED TRADEMARK OF SPORT MASKA INC. AND IS USED UNDER LICENSE BY REEBOK-CCM HOCKEY, U.S., INC. Contents Ontario Hockey League Individual Records 136 Ontario Hockey League Directory 4 Awards and Trophies BE History of the OHL 6 Team Trophies 140 Individual Trophies 143 Member Teams Canadian Hockey League Awards 154 Barrie Colts 8 OHL Graduates in the Hall of Fame 155 s Erie Otter 11 Flint Firebirds 14 All-Star Teams AHEAD mGuelph Stor 17 All-Star Teams 156 Hamilton Bulldogs 20 All-Rookie Teams 161 OF THE Kingston Frontenacs 23 Kitchener Rangers 26 2016 OHL Playoffs London Knights 29 Robertson Cup 164 Mississauga Steelheads 32 OHL Championship Rosters 165 Niagara IceDogs 35 Playoff Records 168 North Bay Battalion 38 Results 169 Oshawa Generals 41 Playoff Scoring Leaders 170 Ottawa 67’s 44 Goaltender Statistics 172 GAME Owen Sound Attack 47 Player Statistics 173 Peterborough Petes 50 2016 OHL Champions photo 178 Saginaw Spirit 53 Sarnia Sting 56 Memorial Cup Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds 59 History 179 Sudbury Wolves 62 All-Star Teams 180 Windsor Spitfires 65 Trophies 181 Records 182 Officiating Staff Directory -

The Nonstatutory Labor Exemption and the Conspiracy Between the NHL and OHL in NHLPA V

Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 1 2007 Icing the Competition: The Nonstatutory Labor Exemption and the Conspiracy between the NHL and OHL in NHLPA v. Plymouth Whalers Hockey Club Thomas Brophy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Thomas Brophy, Icing the Competition: The Nonstatutory Labor Exemption and the Conspiracy between the NHL and OHL in NHLPA v. Plymouth Whalers Hockey Club, 14 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 1 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol14/iss1/1 This Casenote is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Brophy: Icing the Competition: The Nonstatutory Labor Exemption and the C VILLANOVA SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL VOLUME XIV 2007 ISSUE 1 Casenote ICING THE COMPETITION: THE NONSTATUTORY LABOR EXEMPTION AND THE CONSPIRACY BETWEEN THE NHL AND OHL IN NHLPA v. PLYMOUTH WHALERS HOCKEY CLUB I. INTRODUCTION: THE PRE-GAME WARM UP SKATE The New Jersey Devils stressed the team over the individual and won three Stanley Cups in eight years.1 Resulting in some suc- cess, the National Hockey League ("NHL") emphasizes collective bargaining with the National Hockey League Players Association ("NHLPA") over individual bargaining with a player.2 Generally, 1. See Tom Bartunek, Essay; Mystique Keeps Fans in the Seats, N.Y. -

BOSTON BRUINS Vs. WASHINGTON CAPITALS 2008-09 Season Series

2008-09 REGULAR SEASON SCORING No Player GP G A PTS PIM PP SH GW OT Shots %age +/- 91 Marc Savard 82 25 63 88 70 9 - 5 - 213 11.7 +25 46 David Krejci 82 22 51 73 26 5 2 6 1 146 15.1 +37 28 Mark Recchi/Tampa Bay 62 13 32 45 20 2 - 1 - 97 13.4 -15 /Boston 18 10 6 16 2 4 - 2 1 32 31.3 - 3 /Total 80 23 38 61 22 6 - 3 1 129 17.8 -18 81 Phil Kessel 70 36 24 60 16 8 - 6 - 232 15.5 +23 73 Michael Ryder 74 27 26 53 26 10 - 7 - 185 14.6 +28 33 Zdeno Chara 80 19 31 50 95 11 - 3 - 216 8.8 +23 6 Dennis Wideman 79 13 37 50 34 6 1 2 1 169 7.7 +32 26 Blake Wheeler 81 21 24 45 46 3 2 3 - 150 14.0 +36 12 Chuck Kobasew 68 21 21 42 56 6 - 3 - 129 16.3 + 5 17 Milan Lucic 72 17 25 42 136 2 - 3 - 97 17.5 +17 37 Patrice Bergeron 64 8 31 39 16 1 1 1 - 155 5.2 + 2 11 P. J. Axelsson 75 6 24 30 16 2 - - - 87 6.9 - 1 48 Matt Hunwick 53 6 21 27 31 - - 1 - 58 10.3 +15 23 Steve Montador/Anaheim 65 4 16 20 125 - - - - 100 4.0 +14 /Boston 13 - 1 1 18 - - - - 17 0.0 + 3 /Total 78 4 17 21 143 - - - - 117 3.4 +17 18 Stephane Yelle 77 7 11 18 32 1 - 2 - 72 9.7 + 6 45 Mark Stuart 82 5 12 17 76 - - 1 - 61 8.2 +20 21 Andrew Ference 47 1 15 16 40 1 - - - 72 1.4 + 7 16 Marco Sturm 19 7 6 13 8 4 - - - 45 15.6 + 9 34 Shane Hnidy 65 3 9 12 45 1 - 1 - 49 6.1 + 6 22 Shawn Thornton 79 6 5 11 123 - - 2 - 136 4.4 - 2 44 Aaron Ward 65 3 7 10 44 - 1 - - 53 5.7 +16 61 Byron Bitz 35 4 3 7 18 - - - - 31 12.9 Evn 60 Vladimir Sobotka 25 1 4 5 10 - - - - 19 5.3 -10 47 Martin St. -

Toronto Maple Leafs 2009-10 Schedule

TORONTO MARLIES 2009-10 2009-10 FEEL THE SPIRIT 2008-09 TORONTO MARLIES MEDIA GUIDE TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS Toronto Maple Leafs 2009-10 Schedule SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT MTL WSH OCT 127:00 CBC 3 7:00 CBC OTT PIT 456789107:00 TSN 7:00 CBC NYR COL NYR 11 127:00 RSN 137:30 LTV 14 15 16 17 7:00 CBC VAN 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 7:00 CBC ANA DAL BUF MTL 25 2610:00 LTV27 28 8:00 TSN29 30 7:30 RSN 31 7:00 CBC NOV TBL CAR DET 123457:30 RSN 6 7:00 LTV 7 7:00 CBC MIN CHI CGY 8 9 107:00 RSN 11 12 13 8:30 RSN 14 7:00 CBC OTT CAR WSH 0]SfTS^]½cVXeTX]7TaT½bc^cWTPcW[TcTbfW^Z]^fXcP]SP 15 16 177:30 RSN18 19 7:00 TSN 20 21 7:00 CBC NYI TBL FLA 22 237:00 RSN 24 257:00 TSN26 27 7:30 LTV 28 BUF 8]cWXbR^d]cahcWTaT½bPf^aSU^aVTccX]VcWX]VbS^]T8c\TP] 29 307:00 RSN MTL CBJ BOS DEC 17:30 TSN2 3 7:00 LTV4 5 7:00 CBC <^[b^]2P]PSXP]Xb_a^dSc^QTcWT^UÄRXP[QTTabd__[XTa^UcWT ATL NYI BOS WSH 67897:00 RSN 7:00 TSN 107:00 LTV 11 12 7:00 CBC OTT PHX BUF BOS 13 147:00 RSN 15 16 7:30 TSN 17 18 7:30 TSN 19 7:00 CBC BUF NYI MTL 20 217:00 RSN 22 237:00 LTV 24 25 26 7:00 CBC PIT EDM 277:00 LTV28 29 30 9:30 RSN 31 CGY JAN 1 2 7:00 CBC FLA PHI BUF PIT 3457:00 RSN 67:00 TSN7 8 7:30 RSN 9 7:00 CBC CAR PHI WSH 10 11 127:00 RSN 13 14 7:00 TSN 15 7:00 TSN 16 NSH ATL TBL FLA 17 188:00 RSN 19 7:00 LTV20 21 7:00 TSN22 23 7:00 CBC LAK NJD VAN 24 25 267:00 RSN 27 28 29 7:00 TSN 30 7:00 CBC 31 NJD NJD OTT FEB 12347:00 RSN 5 7:00 RSN 6 7:00 CBC SJS STL 7 87:00 RSN 9101112 8:00 LTV 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 [[2P]PSXP]bfW^bW^fXc CAR BOS OTT MAR 1237:00 RSN 47:00 TSN5 6 7:00 CBC ! -

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ______

RECOMMENDED FOR FULL-TEXT PUBLICATION Pursuant to Sixth Circuit Rule 206 File Name: 05a0344p.06 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT _________________ NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE PLAYERS X ASSOCIATION, et al., - Plaintiffs-Appellants, - - No. 04-1173 - v. > , - PLYMOUTH WHALERS HOCKEY CLUB, et al., - Defendants-Appellees. - - N Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan at Detroit. No. 01-70968—Victoria A. Roberts, District Judge. Argued: February 4, 2005 Decided and Filed: August 15, 2005 Before: SILER, COLE, and CLAY, Circuit Judges. _________________ COUNSEL ARGUED: Michael P. Conway, GRIPPO & ELDEN LLC, Chicago, Illinois, for Appellants. Stephen F. Wasinger, WASINGER, KICKHAM & HANLEY, Royal Oak, Michigan, for Appellees. ON BRIEF: John E. Bucheit, John R. McCambridge, GRIPPO & ELDEN LLC, Chicago, Illinois, for Appellants. Stephen F. Wasinger, Gregory D. Hanley, WASINGER, KICKHAM & HANLEY, Royal Oak, Michigan, for Appellees. _________________ OPINION _________________ CLAY, Circuit Judge. Plaintiffs, the National Hockey League Players Association (“NHLPA”), Anthony Aquino (“Aquino”), and Edward Caron (“Caron”) appeal the dismissal, pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, of their suit under the Sherman Antitrust Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1, against Defendants, the Ontario Hockey League (“OHL”), its member Clubs, and its Commissioner, David Branch (“Branch”). This case is before this Court for the second time. In 2003, we reversed the district court’s grant of a preliminary injunction to Plaintiffs, on the ground that Plaintiffs had failed to identify a relevant market as required under the Sherman Act. Nat’l Hockey League Players Ass’n v. Plymouth Whalers Hockey Club (“NHLPA I”), 325 F.3d 712, 714-17 (6th Cir. -

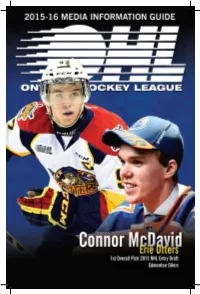

2015-16 OHL Information Guide

15-16 OHL Guide Ad-Print.pdf 1 7/30/2015 2:02:27 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 15-16 OHL Guide Ad-Print.pdf 1 7/30/2015 2:02:27 PM Contents Ontario Hockey League Awards and Trophies Ontario Hockey League Directory 4 Team Trophies 128 History of the OHL 6 Individual Trophies 131 Canadian Hockey League Awards 142 Member Teams OHL Graduates in the Hall of Fame 143 Barrie Colts 8 Erie Otters 11 All-Star Teams Flint Firebirds 14 All-Star Teams 144 Guelph Storm 17 All-Rookie Teams 149 Hamilton Bulldogs 20 Kingston Frontenacs 23 2015 OHL Playoffs Kitchener Rangers 26 Robertson Cup 152 London Knights 29 OHL Championship Rosters 153 Mississauga Steelheads 32 Playoff Records 156 Niagara IceDogs 35 Results 157 North Bay Battalion 38 Playoff Scoring Leaders 158 Oshawa Generals 41 Goaltender Statistics 160 Ottawa 67’s 44 Player Statistics 161 Owen Sound Attack 47 2015 OHL Champions photo 166 C Peterborough Petes 50 M Saginaw Spirit 53 Memorial Cup Sarnia Sting 56 History 167 Y Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds 59 All-Star Teams 168 CM Sudbury Wolves 62 Trophies 169 Windsor Spitfires 65 Records 170 MY Ontario teams to win the Memorial Cup 172 CY Officiating Staff Directory 68 NHL Draft CMY 2014-15 Season in Review Results of the 2015 NHL Draft 174 K Team Standings 69 OHL Honour Roll 176 Scoring Leaders 69 Goaltending Leaders 71 All-Time Coaching Leaders 178 Coaches Poll 72 Goaltender Statistics 73 Media Directory Player Statistics 75 OHL Media Policies 179 Historical Season Results 84 OHL Media Contacts 180 Media covering the OHL 181 Records Team Records 120 2015-16 OHL Schedule 182 Individual Records 124 The 2015-16 Ontario Hockey League Information Guide and Player Register is published by the Ontario Hockey League. -

Carolina Hurricanes

CAROLINA HURRICANES NEWS CLIPPINGS • May 12, 2021 Hurricanes’ home-ice advantage won’t be what it usually is against the Predators By Luke DeCock perhaps only a few weeks away -- it does seem like there’s room for rational relaxation under the circumstances, at least Home ice won’t be as much of an advantage as it usually is to the 50 percent mark which was the intent (if not the letter) for the Carolina Hurricanes in the first round of the playoffs. of the guidelines. Yes, the Hurricanes get to host a potential Game 7 against So it wouldn’t be playing favorites if the Hurricanes-uber-fan- the Nashville Predators, but they’ll be limited to around 6,000 governor found a way to get a few more of his compatriots in fans in PNC Arena when the series begins Sunday or the building, especially this close to June 1. Monday, while the Predators will be allowed as many as 14,000 at their home games. “The Governor is continuing to listen to and work with state health officials on pandemic response and the plan is to lift North Carolina’s COVID capacity restrictions are likely to be mandatory capacity limits by the end of the month,” a loosened June 1, Gov. Roy Cooper has said, but the state spokesperson for the governor wrote in an email. “We has rejected the Hurricanes’ request to allow more fans in understand that businesses and teams are eager to welcome the arena in the two weeks of playoff hockey before then. -

2005-2006 Parkhurst Hockey

2005-2006 Parkhurst Hockey Page 1 of 5 Anaheim Ducks Buffalo Sabres Chicago Blackhawks 1 Andy McDonald 50 Ales Kotalik 101 Brandon Bochenski RC 2 Teemu Selanne 51 Maxim Afinogenov 102 Kyle Calder 3 Scott Niedermayer 52 Chris Drury 103 Mark Bell 4 Joffrey Lupul 53 Tim Connolly 104 Martin Lapointe 5 Todd Marchant 54 Ryan Miller 105 Pavel Vorobiev 6 Chris Kunitz 55 Brian Campbell 106 Nikolai Khabibulin 7 Jean-Sebastien Giguere 56 Jochen Hecht 107 Craig Anderson 8 Samuel Pahlsson 57 Teppo Numminen 108 Matthew Barnaby 9 Jonathan Hedstrom 58 Martin Biron 109 Radim Vrbata 10 Ilya Bryzgalov 59 Derek Roy 110 Rene Bourque RC 11 Jeff Friesen 60 Mike Grier 111 Eric Daze 12 Rob Niedermayer 61 Paul Gaustad 112 Tuomo Ruutu 13 Francois Beauchemin 62 Daniel Briere 113 Adrian Aucoin 14 Vitali Vishnevsky 63 Jason Pominville 114 Jim Vandermeer 15 Ruslan Salei 64 Jay McKee 115 Milan Bartovic 16 Todd Fedoruk 65 J.P. Dumont 116 Curtis Brown 17 Dustin Penner RC 66 Henrik Tallinder Colorado Avalanche Atlanta Thrashers Calgary Flames 117 Alex Tanguay 18 Ilya Kovalchuk 67 Jarome Iginla 118 Joe Sakic 19 Marc Savard 68 Daymond Langkow 119 Marek Svatos 20 Marian Hossa 69 Kristian Huselius 120 Jose Theodore 21 Vyacheslav Kozlov 70 Tony Amonte 121 Andrew Brunette 22 Peter Bondra 71 Andrew Ference 122 Milan Hejduk 23 Jaroslav Modry 72 Chuck Kobasew 123 John-Michael Liles 24 Greg De Vries 73 Miikka Kiprusoff 124 Rob Blake 25 Niclas Havelid 74 Robyn Regehr 125 Pierre Turgeon 26 Patrik Stefan 75