Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014-15 Hockey Hall of Fame Donor List

2014-15 Hockey Hall of Fame Donor List The Hockey Hall of Fame would like to express its sincere appreciation to the following donors: Leagues/Associations: American Hockey League, Canadian Deaf Ice Hockey Federation, Canadian Hockey League, College Hockey Inc., ECHL, National Hockey League, Ontario Junior Hockey League, Ontario Women's Hockey Association, Quebec International Pee-Wee Hockey Tournament, Quebec Major Junior Hockey League, Western Hockey League Companies/Organizations: 90th Parallel Productions Ltd., City of Windsor, CloutsnChara, Golf Canada, Historica Canada, Ilitch Holdings, Inc., MTM Equipment Rentals, Nike Hockey, Nova Scotia Sports Hall of Fame, ORTEMA GmbH, Penn State All-Sports Museum, Sport Entertainment Atlantic, The MeiGray Group IIHF Members: International Ice Hockey Federation, Champions Hockey League, Hockey Canada, Czech Ice Hockey Association, Denmark Ishockey Union, Ice Hockey Federation of Russia, Slovak Ice Hockey Federation, Ice Hockey Federation of Slovenia, Swedish Ice Hockey Association, Swiss Ice Hockey, USA Hockey Hockey Clubs: Allen Americans, Anaheim Ducks, Belleville Bulls, Boston Bruins, Chicago Blackhawks, Columbus Blue Jackets, Connecticut Wolf Pack, Detroit Red Wings, Florida Panthers, Kalamazoo Wings, Kelowna Rockets, Los Angeles Kings, Melbourne Mustangs, Michigan Technological University Huskies, Montreal Canadiens, Newmarket Hurricanes, Ontario Reign, Orlando Solar Bears, Oshawa Generals, Ottawa Senators, Pittsburgh Penguins, Providence College Friars, Quebec Remparts, Rapid City Rush, Rimouski Oceanic, San Jose Sharks, Syracuse Crunch, Tampa Bay Lightning, Toledo Walleye, Toronto Maple Leafs, Toronto Nationals, University of Alberta Golden Bears, University of Manitoba Bisons, University of Massachusetts Minutemen, University of Saskatchewan Huskies, University of Western Ontario Mustangs, Utah Grizzlies, Vancouver Canucks, Vancouver Giants, Washington Capitals, Wheeling Nailers, Youngstown Phantoms Individuals: DJ Abisalih, Jim Agnew, Jan Albert, Mike Aldrich, Kent Angus, Sharon Arend, Michael Auksi, Peter J. -

1977-78 Topps Hockey Card Set Checklist

1977-78 TOPPS HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Marcel Dionne Goals Leaders 2 Tim Young Assists Leaders 3 Steve Shutt Scoring Leaders 4 Bob Gassoff Penalty Minute Leaders 5 Tom Williams Power Play Goals Leaders 6 Glenn "Chico" Resch Goals Against Average Leaders 7 Peter McNab Game-Winning Goal Leaders 8 Dunc Wilson Shutout Leaders 9 Brian Spencer 10 Denis Potvin Second Team All-Star 11 Nick Fotiu 12 Bob Murray 13 Pete LoPresti 14 J.-Bob Kelly 15 Rick MacLeish 16 Terry Harper 17 Willi Plett RC 18 Peter McNab 19 Wayne Thomas 20 Pierre Bouchard 21 Dennis Maruk 22 Mike Murphy 23 Cesare Maniago 24 Paul Gardner RC 25 Rod Gilbert 26 Orest Kindrachuk 27 Bill Hajt 28 John Davidson 29 Jean-Paul Parise 30 Larry Robinson First Team All-Star 31 Yvon Labre 32 Walt McKechnie 33 Rick Kehoe 34 Randy Holt RC 35 Garry Unger 36 Lou Nanne 37 Dan Bouchard 38 Darryl Sittler 39 Bob Murdoch 40 Jean Ratelle 41 Dave Maloney 42 Danny Gare Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Jim Watson 44 Tom Williams 45 Serge Savard 46 Derek Sanderson 47 John Marks 48 Al Cameron RC 49 Dean Talafous 50 Glenn "Chico" Resch 51 Ron Schock 52 Gary Croteau 53 Gerry Meehan 54 Ed Staniowski 55 Phil Esposito 56 Dennis Ververgaert 57 Rick Wilson 58 Jim Lorentz 59 Bobby Schmautz 60 Guy Lapointe Second Team All-Star 61 Ivan Boldirev 62 Bob Nystrom 63 Rick Hampton 64 Jack Valiquette 65 Bernie Parent 66 Dave Burrows 67 Robert "Butch" Goring 68 Checklist 69 Murray Wilson 70 Ed Giacomin 71 Atlanta Flames Team Card 72 Boston Bruins Team Card 73 Buffalo Sabres Team Card 74 Chicago Blackhawks Team Card 75 Cleveland Barons Team Card 76 Colorado Rockies Team Card 77 Detroit Red Wings Team Card 78 Los Angeles Kings Team Card 79 Minnesota North Stars Team Card 80 Montreal Canadiens Team Card 81 New York Islanders Team Card 82 New York Rangers Team Card 83 Philadelphia Flyers Team Card 84 Pittsburgh Penguins Team Card 85 St. -

2009-2010 Colorado Avalanche Media Guide

Qwest_AVS_MediaGuide.pdf 8/3/09 1:12:35 PM UCQRGQRFCDDGAG?J GEF³NCCB LRCPLCR PMTGBCPMDRFC Colorado MJMP?BMT?J?LAFCÍ Upgrade your speed. CUG@CP³NRGA?QR LRCPLCRDPMKUCQR®. Available only in select areas Choice of connection speeds up to: C M Y For always-on Internet households, wide-load CM Mbps data transfers and multi-HD video downloads. MY CY CMY For HD movies, video chat, content sharing K Mbps and frequent multi-tasking. For real-time movie streaming, Mbps gaming and fast music downloads. For basic Internet browsing, Mbps shopping and e-mail. ���.���.���� qwest.com/avs Qwest Connect: Service not available in all areas. Connection speeds are based on sync rates. Download speeds will be up to 15% lower due to network requirements and may vary for reasons such as customer location, websites accessed, Internet congestion and customer equipment. Fiber-optics exists from the neighborhood terminal to the Internet. Speed tiers of 7 Mbps and lower are provided over fiber optics in selected areas only. Requires compatible modem. Subject to additional restrictions and subscriber agreement. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Copyright © 2009 Qwest. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Joe Sakic ...........................................................................2-3 FRANCHISE RECORD BOOK Avalanche Directory ............................................................... 4 All-Time Record ..........................................................134-135 GM’s, Coaches ................................................................. -

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup Calgary Flames Edmonton Oilers St. Louis Blues 2 Flames logo 50 Oilers logo 98 Blues logo 3 Flames uniform 51 Oilers uniform 99 Blues uniform 4 Mike Vernon 52 Grant Fuhr 100 Greg Millen 5 Al MacInnis 53 Charlie Huddy 101 Brian Benning 6 Brad McCrimmon 54 Kevin Lowe 102 Gordie Roberts 7 Gary Suter 55 Steve Smith 103 Gino Cavallini 8 Mike Bullard 56 Jeff Beukeboom 104 Bernie Federko 9 Hakan Loob 57 Glenn Anderson 105 Doug Gilmour 10 Lanny McDonald 58 Wayne Gretzky 106 Tony Hrkac 11 Joe Mullen 59 Jari Kurri 107 Brett Hull 12 Joe Nieuwendyk 60 Craig MacTavish 108 Mark Hunter 13 Joel Otto 61 Mark Messier 109 Tony McKegney 14 Jim Peplinski 62 Craig Simpson 110 Rick Meagher 15 Gary Roberts 63 Esa Tikkanen 111 Brian Sutter 16 Flames team photo (left) 64 Oilers team photo (left) 112 Blues team photo (left) 17 Flames team photo (right) 65 Oilers team photo (right) 113 Blues team photo (right) Chicago Blackhawks Los Angeles Kings Toronto Maple Leafs 18 Blackhawks logo 66 Kings logo 114 Maple Leafs logo 19 Blackhawks uniform 67 Kings uniform 115 Maple Leafs uniform 20 Bob Mason 68 Glenn Healy 116 Alan Bester 21 Darren Pang 69 Rolie Melanson 117 Ken Wregget 22 Bob Murray 70 Steve Duchense 118 Al Iafrate 23 Gary Nylund 71 Tom Laidlaw 119 Luke Richardson 24 Doug Wilson 72 Jay Wells 120 Borje Salming 25 Dirk Graham 73 Mike Allison 121 Wendel Clark 26 Steve Larmer 74 Bobby Carpenter 122 Russ Courtnall 27 Troy Murray -

Vancouver Canucks 2009 Playoff Guide

VANCOUVER CANUCKS 2009 PLAYOFF GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS VANCOUVER CANUCKS TABLE OF CONTENTS Company Directory . .3 Vancouver Canucks Playoff Schedule. 4 General Motors Place Media Information. 5 800 Griffiths Way CANUCKS EXECUTIVE Vancouver, British Columbia Chris Zimmerman, Victor de Bonis. 6 Canada V6B 6G1 Mike Gillis, Laurence Gilman, Tel: (604) 899-4600 Lorne Henning . .7 Stan Smyl, Dave Gagner, Ron Delorme. .8 Fax: (604) 899-4640 Website: www.canucks.com COACHING STAFF Media Relations Secured Site: Canucks.com/mediarelations Alain Vigneault, Rick Bowness. 9 Rink Dimensions. 200 Feet by 85 Feet Ryan Walter, Darryl Williams, Club Colours. Blue, White, and Green Ian Clark, Roger Takahashi. 10 Seating Capacity. 18,630 THE PLAYERS Minor League Affiliation. Manitoba Moose (AHL), Victoria Salmon Kings (ECHL) Canucks Playoff Roster . 11 Radio Affiliation. .Team 1040 Steve Bernier. .12 Television Affiliation. .Rogers Sportsnet (channel 22) Kevin Bieksa. 14 Media Relations Hotline. (604) 899-4995 Alex Burrows . .16 Rob Davison. 18 Media Relations Fax. .(604) 899-4640 Pavol Demitra. .20 Ticket Info & Customer Service. .(604) 899-4625 Alexander Edler . .22 Automated Information Line . .(604) 899-4600 Jannik Hansen. .24 Darcy Hordichuk. 26 Ryan Johnson. .28 Ryan Kesler . .30 Jason LaBarbera . .32 Roberto Luongo . 34 Willie Mitchell. 36 Shane O’Brien. .38 Mattias Ohlund. .40 Taylor Pyatt. .42 Mason Raymond. 44 Rick Rypien . .46 Sami Salo. .48 Daniel Sedin. 50 Henrik Sedin. 52 Mats Sundin. 54 Ossi Vaananen. 56 Kyle Wellwood. .58 PLAYERS IN THE SYSTEM. .60 CANUCKS SEASON IN REVIEW 2008.09 Final Team Scoring. .64 2008.09 Injury/Transactions. .65 2008.09 Game Notes. 66 2008.09 Schedule & Results. -

View Program

23rd Annual SMITHERS CELEBRITY GOLF TOURNAMENT 2015 Contents Bulkley Valley Health Care & Hospital Foundation ........ 2 Message from the Chairmen ........................ 3 Tournament Rules ................................ 4 Calcutta Rules ................................... 5 rd On Course Activities ............................... 6 23 Annual Course map ..................................... 8 Schedule of Events ............................... 10 SMITHERS Sponsor Advertisers Index ......................... 11 Hole-in-One Sponsors. .11 Other Sponsors .................................. 11 CELEBRITY GOLF History of the Celebrity Golf Tournament .............. 12 Aaron Pritchett ............................. 14 Angus Reid ................................ 14 TOURNAMENT Bobby Orr ................................. 16 Brandon Manning ........................... 20 Chanel Beckenlehner ........................ 22 Charlie Simmer ............................. 22 August 13 – 15, 2015 Dan Hamhuis .............................. 24 Smithers Golf & Country Club Dennis Kearns .............................. 24 Faber Drive ................................ 26 Garret Stroshein ............................ 28 Geneviève Lacasse .......................... 28 Harold Snepsts ............................. 34 Jack McIlhargey ............................ 36 Jamie McCartney ............................ 36 Jeff Carlson, Steve Carlson, Dave Hanson ......... 38 Jessica Campbell ........................... 40 Jim Cotter ................................. 40 Jimmy Watson -

Hockey Trivia Questions

Hockey Trivia Questions 1. Q: What hockey team has won the most Stanley cups? A: Montreal Canadians 2. Who scored a record 10 hat tricks in one NHL season? A: Wayne Gretzky 3. Q: What hockey speedster is nicknamed the Russian Rocket? A: Pavel Bure 4. Q: What is the penalty for fighting in the NHL? A: Five minutes in the penalty box 5. Q: What is the Maurice Richard Trophy? A: Given to the player who scores the most goals during the regular season 6. Q: Who is the NHL’s all-time leading goal scorer? A: Wayne Gretzky 7. Q: Who was the first defensemen to win the NHL- point scoring title? A: Bobby Orr 8. Q: Who had the most goals in the 2016-2017 regular season? A: Sidney Crosby 9. Q: What NHL team emerges onto the ice from the giant jaws of a sea beast at home games? A: San Jose Sharks 10. Q: Who is the player to hold the record for most points in one game? A: Darryl Sittler (10 points, in one game – 6 g, 4 a) 11. Q: Which team holds the record for most goals scored in one game? A: Montreal Canadians (16 goals in 1920) 12. Q: Which team won 4 Stanley Cups in a row? A: New York Islanders 13. Q: Who had the most points in the 2016-2017 regular season? A: Connor McDavid 14. Q: Who had the best GAA average in the 2016-2017 regular season? A: Sergei Bobrovsky, GAA 2.06 (HINT: Columbus Blue Jackets) 15. -

1987 SC Playoff Summaries

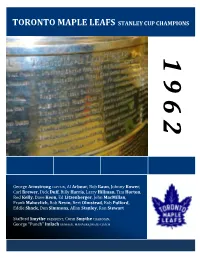

TORONTO MAPLE LEAFS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 1 9 6 2 George Armstrong CAPTAIN, Al Arbour, Bob Baun, Johnny Bower, Carl Brewer, Dick Duff, Billy Harris, Larry Hillman, Tim Horton, Red Kelly, Dave Keon, Ed Litzenberger, John MacMillan, Frank Mahovlich, Bob Nevin, Bert Olmstead, Bob Pulford, Eddie Shack, Don Simmons, Allan Stanley, Ron Stewart Stafford Smythe PRESIDENT, Conn Smythe CHAIRMAN, George “Punch” Imlach GENERAL MANAGER/HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 1962 STANLEY CUP SEMI-FINAL 1 MONTRÉAL CANADIENS 98 v. 3 CHICAGO BLACK HAWKS 75 GM FRANK J. SELKE, HC HECTOR ‘TOE’ BLAKE v. GM TOMMY IVAN, HC RUDY PILOUS BLACK HAWKS WIN SERIES IN 6 Tuesday, March 27 Thursday, March 29 CHICAGO 1 @ MONTREAL 2 CHICAGO 3 @ MONTREAL 4 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD NO SCORING 1. CHICAGO, Bobby Hull 1 (Bill Hay, Stan Mikita) 5:26 PPG 2. MONTREAL, Dickie Moore 2 (Bill Hicke, Ralph Backstrom) 15:10 PPG Penalties – Moore M 0:36, Horvath C 3:30, Wharram C Fontinato M (double minor) 6:04, Fontinato M 11:00, Béliveau M 14:56, Nesterenko C 17:15 Penalties – Evans C 1:06, Backstrom M 3:35, Moore M 8:26, Plante M (served by Berenson) 9:21, Wharram C 14:05, Fontinato M 17:37 SECOND PERIOD NO SCORING SECOND PERIOD 3. -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

1965-66 Toronto Maple Leafs 1965-66 Detroit Red Wings 1965

1965-66 Montreal Canadiens 1965-66 Chicago Blackhawks W L T W L T 41 21 8 OFF 3.41 37 25 8 OFF 3.43 DEF 2.47 DEF 2.67 PLAYER POS GP G A PTS PIM G A PIM PLAYER POS GP G A PTS PIM G A PIM Bobby Rousseau RW 70 30 48 78 20 13 12 2 C Bobby Hull LW 65 54 43 97 70 23 11 9 A Jean Beliveau C 67 29 48 77 50 25 24 8 B Stan Mikita F 68 30 48 78 58 35 23 16 B Henri Richard F 62 22 39 61 47 34 34 13 B Phil Esposito C 69 27 26 53 49 46 30 22 B Claude Provost RW 70 19 36 55 38 42 44 18 B Bill Hay C 68 20 31 51 20 55 38 24 C Gilles Tremblay LW 70 27 21 48 24 53 49 20 B Doug Mohns F 70 22 27 49 63 64 45 32 B Dick Duff LW 63 21 24 45 78 62 55 29 A Chico Maki RW 68 17 31 48 41 71 53 37 B Ralph Backstrom C 67 22 20 42 10 71 60 30 C Ken Wharram C 69 26 17 43 28 82 57 41 B J.C. Tremblay D 59 6 29 35 8 74 67 31 C Eric Nesterenko C 67 15 25 40 58 88 63 48 B Claude Larose RW 64 15 18 33 67 80 72 39 A Pierre Pilote D 51 2 34 36 60 89 72 55 B Jacques Laperriere D 57 6 25 31 85 82 78 49 A Pat Stapleton D 55 4 30 34 52 91 80 62 B Yvan Cournoyer F 65 18 11 29 8 90 81 49 C Ken Hodge RW 63 6 17 23 47 93 84 67 B John Ferguson RW 65 11 14 25 153 95 85 67 A Doug Jarrett D 66 4 12 16 71 95 87 76 A Jean-Guy Talbot D 59 1 14 15 50 - 88 73 B Matt Ravlich D 62 0 16 16 78 - 91 86 A Ted Harris D 53 0 13 13 87 - 92 82 A Lou Angotti (fr NYR) RW 30 4 10 14 12 97 94 87 C Terry Harper D 69 1 11 12 91 - 94 93 A Len Lunde LW 24 4 7 11 4 99 96 88 C Jim Roberts D 70 5 5 10 20 97 96 95 C Elmer Vasko D 56 1 7 8 44 - 97 93 B Dave Balon LW 45 3 7 10 24 98 97 98 B Dennis Hull LW 25 1 5 6 6 -

Sabres Keep Vanek by Matching Oilers' $50M Offer - USATODAY.Com

1/29/13 Sabres keep Vanek by matching Oilers' $50M offer - USATODAY.com Cars Auto Financing Event Tickets Jobs Real Estate Online Degrees Business Opportunities Shopping Search How do I find it? Subscribe to paper Become a member of the USA Home News Travel Money Sports Life Tech Weather Log in Sports » NHL Fantasy Mucking and Grinding Team Pages Scores Standings Statistics Schedules Odds/Matchups More Hockey Buffalo Sabres Buy Sabres Tickets Featured video Team report Schedule Salaries Roster Depth chart Player notes Injuries Transactions Statistics Sabres keep Vanek by matching Oilers' $50M offer Royal family Charlie Sheen Updated 7/6/2007 5:16 PM | Comment | Recommend E-mail | Print | Can w edding Actor seeks boost monarchy's custody of tw ins. By Kevin Allen, USA TODAY popularity? More: Video THE VANEK OFFER IN CONTEXT The Buffalo Sabres had seven days to match the Edmonton Oilers' stunning seven-year, $50 million Digg What's this? offer to 23-year-old restricted free agent Thomas There were four major offer sheets to restricted Vanek, but the Sabres didn't even need seven del.icio.us free agents in the last collective-bargaining agreement and one in the current one before minutes to match the offer. New svine Friday's offer by the Edmonton Oilers to the Reddit Buffalo Sabres' Thomas Vanek. A look: "The message is that we aren't going to become a farm team for the other NHL teams," said Buffalo Facebook 1995 - Keith Tkachuk: The Chicago Blackhaw ks general manager Darcy Regier. gave Winnipeg Jets left w ing Keith Tkachuk a What's this? five-year, $17.2 million offer that paid $6 million in the first year. -

2021 Nhl Awards Presented by Bridgestone Information Guide

2021 NHL AWARDS PRESENTED BY BRIDGESTONE INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 NHL Award Winners and Finalists ................................................................................................................................. 3 Regular-Season Awards Art Ross Trophy ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................. 6 Calder Memorial Trophy ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Frank J. Selke Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Hart Memorial Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 18 Jack Adams Award .................................................................................................................................................. 24 James Norris Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................ 28 Jim Gregory General Manager of the Year Award .................................................................................................