Unit 1 Indian Aesthetics: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets

Voices from the Margins: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets by Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2016 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2018 © Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes 2018 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, a thesis/dissertation entitled: Voices from the Margins: Aesthetics, Subjectivity, and Classical Sanskrit Women Poets submitted by Kathryn Marie Sloane Geddes in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Asian Studies Examining Committee: Adheesh Sathaye, Asian Studies Supervisor Thomas Hunter, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member Anne Murphy, Asian Studies Supervisory Committee Member Additional Examiner ii Abstract In this thesis, I discuss classical Sanskrit women poets and propose an alternative reading of two specific women’s works as a way to complicate current readings of Classical Sanskrit women’s poetry. I begin by situating my work in current scholarship on Classical Sanskrit women poets which discusses women’s works collectively and sees women’s work as writing with alternative literary aesthetics. Through a close reading of two women poets (c. 400 CE-900 CE) who are often linked, I will show how these women were both writing for a courtly, educated audience and argue that they have different authorial voices. In my analysis, I pay close attention to subjectivity and style, employing the frameworks of Sanskrit aesthetic theory and Classical Sanskrit literary conventions in my close readings. -

Sanskrit Literature and the Scientific Development in India

SANSKRIT LITERATURE AND THE SCIENTIFIC DEVELOPMENT IN INDIA By : Justice Markandey Katju, Judge, Supreme Court of India Speech delivered on 27.11.2010 at Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi Friends, It is an honour for me to be invited to speak in this great University which has produced eminent scholars, many of them of world repute. It is also an honour for me to be invited to Varanasi, a city which has been a great seat of Indian culture for thousands of years. The topic which I have chosen to speak on today is : ‘Sanskrit Literature and the Scientific Development in India’. I have chosen this topic because this is the age of science, and to progress we must spread the scientific outlook among our masses. Today India is facing huge problems, social, economic and cultural. In my opinion these can only be solved by science. We have to spread the scientific outlook to every nook and corner of our country. And by science I mean not just physics, chemistry and biology but the entire scientific outlook. We must transform our people and make them modern minded. By modern I do not mean wearing a fine suit or tie or a pretty skirt or jeans. A person can be wearing that and yet be backward mentally. By being modern I mean having a modern mind, which means a logical mind, a questioning mind, a scientific mind. The foundation of Indian culture is based on the Sanskrit language. There is a misconception about the Sanskrit language that it is only a language for chanting mantras in temples or religious ceremonies. -

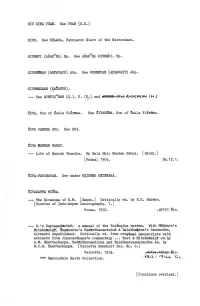

P. ) AV Gereaw (M.) Hitherto Unpublished. Critically Ed. From

SIU KING YUAN. See YUAN (S.K.) SIUD. See SULACA, Patriarch Elect of the Nestorians. SIUNECI (ARAKcEL) Bp. See ARAKcEL SIUNECI, Bp. SIURMEEAN (ARTAVAZD) Abp. See SURMEYAN (ARDAVAZT) Abp. SIURMELEAN (KOATUR). - -- See AVETIKcEAN (G.), S. (K.) and AUCIILR {P. ) AV GEREAw (M.) SIVA, Son of Sukla Visrama. See SIVARAMA, Son of Sukla Visrama. SIVA CANDRA GUI. See GUI. SIVA NANDAN SAHAY. - -- Life of Harish Chandra. By Balm Shio Nandan Sahai. [Hindi.] [Patna] 1905. Br.12.1. SIVA- PARINAYAH. See under KRISHNA RAJANAKA. SIVADATTA MISRA. - -- The Sivakosa of S.M. [Sansk.] Critically ed. by R.G. Harshe. [Sources of Indo -Aryan Lexicography, 7.] Poona, 1952. .49123 Siv. - -- S.'s Saptapadartht; a manual of the Vaisesika system. With Madhava's Mitabhasint, Sesananta's Padarthacandrika & Balabhaadra's Sandarbha, hitherto unpublished. Critically ed. from original manuscripts with extracts from Jinavardhana's commentary ... Text & Mitabhasint ed.by A.M. Bhattacharya, Padarthacandrika and Balabhadrasandarbha ed. by N.C.B. Bhattacharya. [Calcutta Sanskrit Ser. No. 8.] Calcutta, 1934. .6912+.1-4143 giv. * ** Berriedale Keith Collection. [Continued overleaf.] ADDITIONS SIU (BOBBY). - -- Women of China; imperialism and women's resistance, 1900 -1949. Lond., 1982. .3961(5103 -04) Siu. SIVACHEV (NIKOLAY V.). - -- and YAKOVLEV (NIKOLAY N.). - -- Russia and the United States. Tr. by O.A. Titelbaum. [The U.S. in the World: Foreign Perspectives.] Chicago, 1980. .327(73 :47) Siv. gIVADITYA MARA [continued]. - -- Saptapadartht. Ed. with introd., translation and notes by D. Gurumurti. With a foreword by Sir S. Radhakrishnan. [Devanagari and Eng.] Madras, 1932. .8712:.18143 LN: 1 S / /,/t *** Berriedale Keith Collection. 8q12: SIVADJIAN (J.). - -- Les fièvres et les médicaments antithermiques. -

Language of Sanskrit Drama Language of Sanskrit Drama

Language of Sanskrit Drama Saroja BhatBhateeee ljkstk HkkVs egkHkkxk laLÑr:iosQ"kq izkÑrkuka iz;ksxoSfp=;L; dkj.kkfu iz;kstu×p vfUo";Urh HkjrukVÔ'kkL=ks ,rf}"k;dfo/huka fo'ys"k.ka fo/k;] lkekftd&jktdh;&n`"VÔk ojRokojRoiz;qDrr;k izkÑrHkk"kkiz;ksxs oSfoè;a ukVÔ'kkL=klEera O;k[;k;] okLrfod:is.k e`PNdfVd&vfHkKku& 'kkoqQUrykfn:iosQ"kq iz;qDrkuka izkÑrHkk"kkiz;ksxk.kkeuq'khyus rq rÙkkn`'k& fu;ekukeifjikyua foHkkO; egkdkO;sH;% oSy{k.;lEiknua oSfp=;k/ku}kjk lkSUn;Zifjiks"k.ka Dofpr~ lkekftd jktdh;kfHkKkuis{k;k vfrfjDreso fdf×pr~ vlk/kj.ke~ vfHkKkunkua iz;kstua HkforqegZrhfr fuxe;frA An attempt is made here to present a brief account of the language of Sanskrit drama particularly with reference to aspects of identity related to them. Theorists of Sanskrit literature recommend three idioms of poetry: Sanskrit, Prakrit and Apabhraṃśa. We are, for the present, concerned with the first two since they constitute classical dramatic literature of India. Scholars both, traditional as well as modern, record different opinions about the relationship between these two. I follow the generally accepted view. Sanskrit is the name given to an ancient vernacular, which was "refined", "rendered fit", while the word Prakrit stands for a group of vernaculars initially spoken by different communities settled in different parts of ancient India which were later systematically formalized by grammarians and developed into literary idioms. In the beginning Sanskrit and some Prākṛits were very much similar in form, almost like twin sisters. They deviated from each other in the course of time. -

The Lyricism of Kalidasa and the Classical Sanskrit Drama

The Lyricism of Kalidasa and the Classical Sanskrit Drama The World’s Classics lecture series The topics about which I shall speak today… • What is Classical Sanskrit literature? • Who is Kalidasa? Why should we be interested in him? • The lyric drama of Kalidasa, Recognition of Shakuntala • What we can gain from studying Kalidasa’s works. India and the Classics Modern Indian Languages: 1652; 129 languages spoken by more than a million people Official Indian Classical Languages: Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada What makes a language classical? a. “High antiquity of its early texts/recorded history over a period of 1500-2000 years; b. A body of ancient literature/texts, which is considered a valuable heritage by generations of speakers; c. The literary tradition it original and not borrowed from another speech community” Two Distinct but Interrelated Classical Traditions • 1. Dravidian South : Tamil, Kannada, Telugu Indo-European North • Sanskrit and its ancient sisters • These will become Hindi, Gujarati, Bengali etc. Why do we read the classical literature of India? • It has shaped the culture of a major civilization of the world. • It helps us to understand the mind-set of a major portion of the world’s population. • It is full of excellent works that speak to all of us. Classical India: AD 400-1000 • In itself an historical concept = India of the Gupta Emperors • The area covered is huge. • Many different cultures and languages. • Sankrit provides a lingua franca among the educated. The Physical Reality of India of the 1st Millennium of our Era Classical India • The literary legacy of Sanskrit Literature • The Classical Language as standardized by Panini • The literature produced in Classical Sanskrit includes works by Dravidian, Nepali and Sinhalese as well as Indian authors. -

The Journal Ie Music Academy

THE JOURNAL OF IE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY OTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC XIII 1962 Parts I-£V _ j 5tt i TOTftr 1 ®r?r <nr firerftr ii dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, - the Sun; where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, ! ” EDITED BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., PH.D. 1 9 6 2 PUBLISHED BY HE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, M OW BRAY’S RO AD, M ADRAS-14. "iption—Inland Rs, 4. Foreign 8 sh. Post paid. i ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES I S COVER PAGES: if Back (outside) $ if Front (inside) i Back (D o.) if 0 if INSIDE PAGES: if 1st page (after cover) if if Ot^er pages (each) 1 £M E N i if k reference will be given to advertisers of if instruments and books and other artistic wares. if I Special position and special rate on application. Xif Xtx XK XK X&< i - XK... >&< >*< >*<. tG O^ & O +O +f >*< >•< >*« X NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. R Editor, Journal of the Music Academy, Madras-14. Articles on subjects of music and dance are accep publication on the understanding that they are contribute) to the Journal of tlie Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferab written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and be signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for t1 expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement, moneys and cheque ♦ended for the Journal should be sent to D CONTENTS 'le X X X V th Madras Music Conference, 1961 : Official Report Alapa and Rasa-Bhava id wan C. -

A History of Persian Literature Volume XVII Volumes of a History of Persian Literature

A History of Persian Literature Volume XVII Volumes of A History of Persian Literature I General Introduction to Persian Literature II Persian Poetry in the Classical Era, 800–1500 Panegyrics (qaside), Short Lyrics (ghazal); Quatrains (robâ’i) III Persian Poetry in the Classical Era, 800–1500 Narrative Poems in Couplet form (mathnavis); Strophic Poems; Occasional Poems (qat’e); Satirical and Invective poetry; shahrâshub IV Heroic Epic The Shahnameh and its Legacy V Persian Prose VI Religious and Mystical Literature VII Persian Poetry, 1500–1900 From the Safavids to the Dawn of the Constitutional Movement VIII Persian Poetry from outside Iran The Indian Subcontinent, Anatolia, Central Asia after Timur IX Persian Prose from outside Iran The Indian Subcontinent, Anatolia, Central Asia after Timur X Persian Historiography XI Literature of the early Twentieth Century From the Constitutional Period to Reza Shah XII Modern Persian Poetry, 1940 to the Present Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan XIII Modern Fiction and Drama XIV Biographies of the Poets and Writers of the Classical Period XV Biographies of the Poets and Writers of the Modern Period; Literary Terms XVI General Index Companion Volumes to A History of Persian Literature: XVII Companion Volume I: The Literature of Pre- Islamic Iran XVIII Companion Volume II: Literature in Iranian Languages other than Persian Kurdish, Pashto, Balochi, Ossetic; Persian and Tajik Oral Literatures A HistorY of Persian LiteratUre General Editor – Ehsan Yarshater Volume XVII The Literature of Pre-Islamic Iran Companion Volume I to A History of Persian Literature Edited by Ronald E. Emmerick & Maria Macuch Sponsored by Persian Heritage Foundation (New York) & Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University Published in 2009 by I. -

Sanskrit Literature

A HISTORY OF SANSKRIT LITERATURE Oxford University Press, Amen House, London E.C.4 GLASGOW NEW YORK "TOR01"'n"O MEL.BOURNE WELLINGTON BOMBAY CALCUTTA·MADRAS KARACHl CAPE TOWN lBADAN NAlROBI ACCkA 5.lNGAPORE FIRST EDITION 1920 Reprinted photographically in Great Britain in 1941, 1948, 1953, 1956 by LOWE & BRYDONE, PRINTERS, LTD., LONDON from sheets of the first edition A HISTORY OF SANSKRIT LITERATURE BY A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.LI'IT. Of the Inner Temple, Barnster-at-Law, and Advocate Regius Professor of Sansknt and Comparative Philology and Lecturer on the Constitution of the British Empire in the UnIversity of Edinburgh OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Pnnted III Great Bntam IN MEMORIAM FRATRIS ALAN DAVIDSON KEITH (1885-1928) PREFACE AKEN in conjunc"tion with my Sanskrit Drama, published T in 19~4, this work covers the field of Classical Sanskrit Literature, as opposed to the Vedic Literature, the epics, and the PuralJ.as~ To bring the subject-matter within the limits of a single volume has rendered it necessary to treat the scientific literature briefly, and to avoid discussions of its subject-matter which appertain rather to the historian of grammar, philosophy, law, medicine, astronomy, or mathematics, than to the literary his torian. This mode of treatment has rendered it possible, for the first time in any treatise in English on Sanskrit Literature, to pay due attention to the literary qualities of the Kavya. Though it was to Englishmen, such as Sir William Jones and H. T. Cole brooke, that our earliest knowledge of Sanskrit poetry was due, no English poet shared Goethe's marvellous appreciation of the merits of works known to him only through the distorting medium of translations, and attention in England has usually been limited to the Vedic literature, as a source for comparative philology, the history of religion, or Indo-European antiquities; to the mysticism and monism of Sanskrit philosophy; and to the fables and fairy-tales in their relations to western parallels. -

The Importance of the Purā As In

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 05, 2020 CONTEMPORARY SANSKRIT LITERATURE: A BRIEF STUDY. Nipam Nath Dev Sarma. Ph.D scholar, Department of Sanskrit,Assam University, Silchar (Assam). Abstract: The purāṇas has acquired an incomparable disposition in Indian literature. As a literature it has been connected with miscellaneous subjects like religion, philosophy, history, geography, sociology, politics, medicine, domicile, astrology, astronomy, and sacrificial rites etc. the purāṇas are the vast literature which has computed at four lakh verses respecting for Vedic authority to restate the ideals of ancient Indian culture and customs. The Puranas are called the fifth veda. The author of all purāṇas is Vedavyasa. The Purāṇas are as superior as Veda. There are many more works have written on the basis of Paurāṇic legends. The purāṇas are the vital store-house of all subjects. The present paper highlights the importance of the purāṇa in contemporary Sanskrit literature. In this paper the religious aspect, historical aspect, educational aspect, ethical aspects, geographical aspect, social aspect, philosophical aspect and literary aspect are briefly discussed. Keywords: purāṇa, contemporary, Atheism, geography, national unity and integrity etc. The purāṇas has possessed an incredible position in contemporary Sanskrit literature. As a religious literature, the purāṇas are deeply connected with subjects like ancient Indian region, philosophy, ancient history, geography, sociology, politics (Rājnῑtiśāstra), medicine (Ᾱyurveda), Vāstu-śāstra, Sacrificial rituals and so on etc. Besides it deals with the subjects like arts, science, grammar, dramaturgy, music, astrology, astronomy etc. The purāṇas delivers the whole information about the whole subjects to the Sanskrit literature. Many regional literatures develop by acquiring the vital information from the purāṇas in later times. -

Modern Sanskrit Writings in Karnataka

yksdfiz;lkfgR;xzUFkekykµ5 Publisher: Registrar Modern Sanskrit Writings Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan in (Deemed University) 56-57, Institutional Area, KARNATAKA Janakpuri, New Delhi-110058 Tel. : 28520976 Tel. fax : 28524532 © Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan Author S. Ranganath First Edition : 2009 Edited by (Late) Prof. Achyutanand Dash ISBN : 978-81-86111-21-5 Price : Rs. 95/- RASHTRIYA SANSKRIT SANSTHAN Printed at : DEEMED UNIVERSITY Amar Printing Press NEW DELHI Delhi-110009 ( iv ) overloaded with panegyrics and hyperbolism. There is a shift from versification towards prose, from verbal jugglery towards sim- plicity; and the tendency to cultivate the age-old language of gods as a vehicle for expression of contemporary socio-economic con- ditions. PREFACE Karnataka has produced some of the most outstanding This work by Ranganath introduces 38 representative au- litterateurs of Sanskrit in our times. Galgali Ramachar, Jaggu thors from Karnataka belonging to Twentieth Century. They rep- Vakulabhushana and many others have composed some of the resent diverse generations of literary personalities in Sanskrit that finest specimen of creative pieces that can be a part of the golden have prominently flourished in the past century. Many of them, treasure of Sanskrit literature. Tradition and modernity go hand in like S. Jagannath and R Ganesh just carved a niche for them- hand together in these writings. We can also find a blend of clas- selves in twentieth century and now they belong to the generation sicism and modernity. C.G.Purushottam, H.V. Nagaraja Rao, R. of most promising Sanskrit authors in this century. Ganesh and some others have made new experimentations and have introduced new genres. -

The Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office, Varanasi-1 •Prirtkr : Vidya Vilas Press, Varanasi-1 Edition : Second, 1968

WublhhS : The Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office, Varanasi-1 •Prirtkr : Vidya Vilas Press, Varanasi-1 Edition : Second, 1968. Price : Rs. 45-00 This is a Second Edition of the work, revised, enlarged, and re-elaborated by the Author, the First Edition having appeared in the SOR, No. XI, published by 1SMEO ( Jstituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente ), Rome 1956. (C) The Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office PUBLISHERS AND ORIENTAL & FOREIGN BOOK-SELLERS K. 37/99, Gopal Mandir Lane P. O. CHOWKHAMBA, P. BOX 8, VARANASI-1 ( India ) 1968 PUBLISHERS' NOTE ATBËJNAVAGUPTA seems to have given the final shape to the philo- *.*.* -><- £Uty -m india. His name is familiar to all students of Sanskrit ^tî^lanîd.Indian Aesthetics. His fame is still alive and his poetical PmpMlbsöphical theories hold ground even today. It is no wonder |Aë;%esthetic thought of Abhinavagupta, one of the most profound äffest minds that India has ever known, captured the imagination j&aniero Gnoli who, besides being an erudite scholar, well- pÄö'käitor and able translator of various Sanskrit Texts, is a Saludaya l(tiu&, sense of the term. His thorough understanding and scholarly of the Rasa-theory of Abhinavagupta in particular theories of other thinkers in general, are simply wonderful, work, AESTHETIC EXPERIENCE ACCORDING , he has edited and translated the Com- y Abhinavagupta on the famous smra of Bharata, Vibhavânu- ( Nalya sastra ) which constitutes text in the whole of Indian aesthetic thought, and the light of the views of prominent rhetors and philo- ancient and modern. The theory of Abhinavagupta has eô:presented here in a garb which can very easily appeal to of this work was issued some ten years back by the in the SERIE ORIENTALE ROMA ( No. -

Sikh Religion and Hinduism

Sikh Religion and Hinduism G.S.Sidhu M.A.FIL(London) Published by:- Guru Nanak Charitable Trust 1 Contents Opinions ................................................................................................ 8 Acknowledgments ............................................................................... 15 Foreword ............................................................................................. 17 Introduction ......................................................................................... 20 Chapter 1 ............................................................................................. 25 Vedant ................................................................................................. 25 1.1 What is Vedant? ................................................................... 25 1.2 Historical developments ............................................................. 27 1.3 Sikh point of View ..................................................................... 31 Chapter 2 ............................................................................................. 36 The Vedas and Sikhism ........................................................................ 36 2.1 The Vedas .................................................................................. 36 2.2 The importance of the Vedas ...................................................... 38 2.3 The Rig Veda ............................................................................. 39 2.4 Contents of the Rig Veda ...........................................................