Phil Nusbaum MM: Marv Menzel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Monsters of Indie Retail

1. MONSTERS OF INDIE RETAIL ALL KILLER, r NO FILLER ' THE ST I POWE:. i THE G.' EST HITS UM NOVEMBER 27, 2010 www.bii°Iboard.com wwv billboard iz US $6.99 cAN $8 ; $' çs 699000 ZOV£-L0806 VJ H3V38 9N01 3AV N13 OPLE V # V100 A1N3309 AINOW 1111111111111'1111111111111'lllllllllll Z00/000 Z-V1-V 100 ZLaVW#6/83/88N£6IOZi # L06 1I9I0-£ HJS************************* 3313F003# c 71 `/ V Y I L V J Y u Or i Bi' OR 7(ìl0 LATIN G RAMMY "WINNERS ,, nl, ,1'4 r:figrat";vJUAN LUIS GUERRA a\ ALBUM OF THE YEAR I 1 ;I ,BEST CONTEMPORARY TROPICAL ALBUM -417,V 41.i BEST TROPICAL SONG 4.1 11Nf; GILBERTO GIL BEST MPB ALBUM BEST NATIVE BRAZILIAN ROOTS ALEX `CHINO Y NACHO CUBA BEST URBAN MUSIC ALBUM ,SOCAN; BEST NEW ARTIST Pitt e f t 4, ELIDA REYNA Y AVANTE BEST TEJANO ALBUM BANDA EL RECODO FERNANDO OTERO BEST BANDA ALBUM BEST CLASSICAL ALBUM RAFAELLL'AZZiARO ALBUM OF THE YEAR SEBASTIAN PACO LUGO KRYS BEST REGIONAL aj BEST ENGINEERED MEXICAN SONG ALBUM LALOrSCHIFRIN BEST CLASSICAL \ CONTEMPORARY COMPOSITION GRUPO PESADO BEST NORTEÑO ALBUM JULIETA\VENEGÄS BEST SHORT FORM MUSIC JOAO`DONATORTRIO BEST LATIN JAZZ ALBUM S 4 I bmi.com j VOZ VEIS 1 1100.1",. BEST LONGFORM MUSIC VIDEO a ` 1 .%. .4 Billboard 1 ON THE CHARTS ALBUMS PAGE ARTIST /TITLE THE S YLE, BILLBOARD 200 32 THE GIFTIFT JASON A / TOP INDEPENDENT 34 MV KINDA PARTY KIDCUDI/ TOP DIGITAL 34 MAN ON THE MOON It THE LEGEND OF MR. RAGER 34 SUSAN BOYLE / TOP INTERNET TnE GIFT OCEAN WAY / HEATSEEKERS ALBUMS 35 OCEAN WAY SESSIONS (EP) TAYLOR WIFT / TOP COUNTRY 39 SPEAK NOW DIERKS BENTLEY / TOP BLUEGRASS 39 UPON THE RIDGE KID / TOP R &B /HIP -HOP 40 MAN ON THE MOON II'. -

TRAMPLED by TURTLES Life Is Good on the Open Road

TRAMPLED BY TURTLES Life Is Good On The Open Road In the immortal words of Tom Petty, “You belong somewhere you feel free.” For the Duluth, Minnesota sextet Trampled by Turtles, finding that freedom meant taking a risky approach; rather than continuing full speed ahead with a band that had been successfully touring, writing, and recording music together for the past 15 years, they pumped the breaks and brought the tour bus screeching to a halt. By the time Trampled by Turtles announced their hiatus in the fall of 2016, the success they’d experienced as a band could only be described as a phenomenon. They’d had multiple albums climb the Billboard charts, with two reaching the No. 1 spot on the Bluegrass charts and one topping the Folk chart; they’d appeared on The Late Show with David Letterman twice; and they’d performed at nearly every major festival in the U.S. and Canada, from Coachella to Bonnarroo, Lollapalooza, and the Newport Folk Festival, pulling in huge and adoring crowds with their breakneck string performances and heartfelt, sometimes gut- wrenching lyrics. After all that time traveling together in close quarters and commanding festival and club stages around the country, the six musicians who make up Trampled by Turtles — Dave Simonett, Tim Saxhaug, Dave Carroll, Erik Berry, Ryan Young, and Eamonn McLain — went nearly a year without all being in the same room. Simonett, the band’s lead singer and songwriter, released a critically acclaimed and highly personal album, Furnace, with his band Dead Man Winter. Other members kept busy with their own side projects in the Twin Cities and their hometown of Duluth, Minnesota, allowing new musical ideas to grow. -

The Nutcracker's Ballerina 5 Must Love Dogs 5 the Perfect Potluck 7 Readbuzz.Com VOL10 NO50 Decb Em Er 6, 2012

Champaign-Urbana’s community magazine FREE WEEK OF DECEMBER 6 , 2012 more on THE NUTCRACKER'S BALLERINA 5 MUST LOVE DOGS 5 THE PERFECT POTLUCK 7 READBUZZ.COM VOL10 NO50 DECB EM ER 6, 2012 IN THIS ISSUE EDITOR’S NOTE S AMANTHA BAKALL Every year around this time, my mom asks me for a Christ- mas list so she can send it to Santa. Yes, A GUIDE TO SPIRITS 06 I am 22 years old and still believe in Santa. What are you going to do about it? There’s absolutely nothing wrong with having whimsical visions of Santa coming down my chimney, taking a bite out of a cookie that I left out on the requisite “Santa plate,” (my house has a plate specifically for Santa. I don’t really know what it’s from, but it just became a tradition) leaving boxes of unwrapped gifts from Amazon and climbing back up to deliver presents to the other good little boys and girls. My brother is 15 and I am 22. I’m sure we still LO-CAL MUSIC EGGNOGGED fall within that demographic. 10 06 As I’ve gotten older, coming up with things to put on my list has become increasingly difficult. After a certain point, I’ve stopped needing things. Or maybe I finally matured enough to realize that YOUR FAVORITE MOVIE SUCKS the things I need I really don’t need. So this year RESTURANT FOR VEGET04 when my mom asked for Santa’s list in her Face- Is Donnie Darko all cult and nothing more? book inbox, I didn’t have anything to put on it. -

North Carolina Museum of Art Announces Summer Concert and Movie Schedule

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 30, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT Kat Harding | (919) 664-6795 | [email protected] North Carolina Museum of Art Announces Summer Concert and Movie Schedule Lineup features Americana, pop, and indie rock performers, the return of The Big Lebowski movie party, and more Raleigh, N.C.—The North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) is back with its summer season of outdoor concerts and movies. The 22nd annual outdoor performing arts series includes concerts presented with Carrboro-based Cat’s Cradle featuring Old Crow Medicine Show; Triangle-based performers Mipso, Tift Merritt, and Chatham Rabbits; Courtney Barnett, the legendary Chaka Khan, and more. The summer movie lineup includes First Man, The Hate U Give, Roma, and celebrations of the 40th anniversary of Alien and 55th anniversary of Dr. Strangelove. Special movie parties, which feature additional activities, food, and art making before the movie screenings, include Isle of Dogs, Academy Award-winning Bohemian Rhapsody, The Lego Movie 2, and the return of visitor favorite The Dude Abides The Big Lebowski party. This year, one of the movies is a crowdsourced pick from a list of romantic comedy favorites. The winner of the “Battle of the Rom- Coms,” a bracket-style competition pitting romantic comedies from the 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s against each other, screens on Friday, June 7. Visitors can help pick the winner beginning Monday, May 13, on the NCMA’s Instagram account at instagram.com/ncartmuseum. See the full schedule of summer concerts, movies, and movie parties below. Outdoor Concert Series An Evening with Dawes Friday, May 17 (continued) North Carolina Museum of Art Announces Summer Concert and Movie Schedule West Coast stars Dawes playfully experiment with roots-rock and the southern California sound while embracing soul hooks, R&B grooves, and swampy blues. -

Dave Simonett – Red Tail Biography

Dave Simonett – Red Tail Biography Almost two decades into a prolific career, Dave Simonett still leans into a microphone like he’s counting on a stranger. Guitar slung at the ready, he’s comfortable but bemused. He’s fine with the set-up–– grateful, even. It’s just that the mics and the lights have never been the point. “I feel like I’ve gotten more comfortable with my own voice, as I’ve gotten older,” Simonett says, home in Minneapolis. “I’ve kind of settled into myself a bit. The guitar and the microphone have been tools to get my songs out, more than I think of myself as a guitar player or a singer.” Simonett has always been on a stage because of the songs he has to share. But make no mistake: Whether he’s fronting beloved acoustic roots kings Trampled By Turtles or acclaimed side project Dead Man Winter, Simonett can sing. In fact, as much as he may sidestep the compliment, he has an ideal songwriter’s voice––a beautiful but subtle workhorse that’s easy to take for granted. But ultimately, he’s right to point to his songs, because oh, what songs they are: Conversational and poetic, his lines lilt with aching cadence as they land like phrases someone would actually say. It’s art that feels real. Entitled Red Tail, Simonett’s new album is a solo outing––his first––that puts a brand new batch of his original nuggets on brilliant display. “There was a special window when I didn’t know if I was making an album––I was just going to record some songs,” Simonett says. -

Minnesota Music Collection @Perpich Library

Minnesota Music Collection @Perpich Library Classical / Opera Minnesota Opera George Antheil's Transatlantic and Music of the Early 20th Century (M1 .G46 1998) Minnesota Orchestra (Osmo Vänskä, conductor) Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony no.1 in C major, op. 21; Symphony no.6 in F major, “Pastoral,” op. 68 (M1001.B4 O86 2007) Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony no.2 in D major, op. 36; Symphony no.7 in A major, op. 92 (M1001.B4 O86 2008) Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony no. 3 in E flat major, “Eroica,” op. 55 Symphony no.8 in F major, op. 93 (M1001.B4 O86 2006) Electronic Music Cook, Trevor Human Disinterest (M1473.C66 H86 1994) Future Perfect Nature of Time (M1473.F88 N38 2001) Gospel Sounds of Blackness The Very Best of Sounds of Blackness (M2198.S68 V47 2001) Jazz Allen, James* and Vicky Mountain Sincerely Yours (M1366.M68 S56 2009) Ancestor Energy Allwhere (PS3551.L435 A53 2004) *Denotes Perpich alumnus or faculty member The Bad Plus Never Stop (M1366.B33 N48 2010) Carei Thomas Feel Free Ensemble Mining our Bid'ness (M1366 .C37 2002) Curlew Mercury (M1366.C87 M8 2003) Happy Apple Youth Oriented (M1366.H37 Y68 2002) Thomas, Carei F. Sound window(s) V pinnacles (M1473.T46 S6 2005) No Light, No Darkness: Jazz Axiom XI (M1366 .T46 2005) Instrumental / Vocal (Miscellaneous) Bayley, Jonathan and Tom Kanthak The Banff Recordings: Improvisations for Flute and Many Instruments (M242 .B39 2001) The Banff Recordings II: Improvisations for Flute and Many More Instruments (M242 .B39 2001b) College of St. Benedict Campus Singers All in the Family: Songs of Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel & Felix Mendelssohn (M1619.H46 A45 1999) Granias, Chris J. -

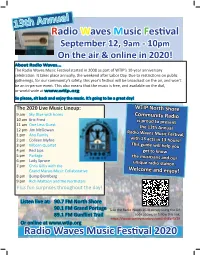

2020 Radio Waves Program Guide

13th Annual Radio Waves Music Festival September 12, 9am - 10pm On the air & online in 2020! About Radio Waves... The Radio Waves Music Festival started in 2008 as part of WTIP’s 10-year anniversary celebration. It takes place annually, the weekend after Labor Day. Due to restrictions on public gatherings, for our community’s safety, this year’s festival will be broadcast on the air, and won’t be an in-person event. This also means that the music is free, and available on the dial, or world wide at www.wtip.org So please, sit back and enjoy the music. It’s going to be a great day! The 2020 Live Music Lineup: WTIP North Shore 9 am Sky Blue with horns Community Radio 10 am Eric Frost is proud to present 11 am One Less Guest the 13th Annual 12 pm Jim McGowan Radio Waves Music Festival, 1 pm Aho Family 2 pm Colleen Myhre with 13 acts in 13 hours! 3 pm Kilborn Quartet This guide will help you 4 pm Red Lips get to know 5 pm Portage the musicians and our 6 pm Lady Spruce unique radio station. 7 pm Chris Gillis with the Grand Marais Music Collaborative Welcome and enjoy! 8 pm Bump Blomberg 9 pm Rich Mattson and the Northstars Plus fun surprises throughout the day! Listen live at: 90.7 FM North Shore 90.1 FM Grand Portage Take the Radio Waves 2020 survey using the QR 89.1 FM Gunflint Trail code above, or follow this link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/H8W5YZR Or online at www.wtip.org Radio Waves Music Festival 2020 Radio Waves Music Festival 2020 Eric Frost has been playing music all his life, and brings an appreciation for rock and roll’s roots to his performances, covering music from the old time, bluegrass, folk and blues traditions. -

Enjoy the Festival but Also Come See All That's New!

2 • MerleFest • Wilkes Journal-Patriot • April 2015 MerleFest brings special shows by over 120 artists MerleFest is known for four days of spe- Mitchell County with William Ritter and cial musical collaborations and themes on 13 Sarah Ogletree at 1 p.m. and by Wayne different stages and this year is no exception. Henderson and Helen White from 3:30 p.m. Ted Hagaman, festival director, said he’s also particularly pleased with the Tributes to Doc and Merle Saturday combination of artists at MerleFest for the Highlights Saturday include three spe- first time and returning festival favorites. cial tributes to Doc and Merle Watson. “Doc’s Show,” hosted by David Holt with Strong Thursday lineup Carol Rifkin and others, is at 10:30 a.m. One of the newcomers, Asheville-based at the Traditional Stage. Underhill Rose, will lead off on the Watson “Memories of Doc and Merle,” hosted by Stage at 3 p.m. Thursday with a blend of T. Michael Coleman with special guests, Americana, R&B, country and bluegrass, is at noon at the Creekside Stage. just 30 minutes after the festival gates open. “Doc Watson Guitar Tribute,” featuring It consists of Eleanor Underhill, Sally Jack Lawrence, David Holt, T. Michael 1430 Second Street 1838 Winkler Street Williamson and Molly Rose. “Joining the Coleman and others, is at 1:45 p.m. on North Wilkesboro Wilkesboro lineup for Merlefest has been a long-time the Watson Stage. goal of ours,” said Underhill in an inter- The popular Hillside Album Hour, view with the Johnson City Press. -

Startribune-DMW.Pdf

ZSW [C M Y K]E12 Sunday, Feb. 5, 2017 E12 • STAR TRIBUNE VARIETY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2017 Dave Simonett in the woods surrounding Pachyderm Studios in Cannon Falls, Minn. “Furnace,” his new album with Dead Man Winter, was recorded there. JEFF WHEELER • [email protected] Simonett takes a winter break ø SIMONETT from E1 Dead Man Winter Even though “Furnace” is With: The Pines, Erik Koskinen. loaded with the electric gui- When: 8 p.m. Fri. tars, drums and organ hardly Where: First Avenue, ever heard on a TBT record, 701 1st Av. N., Mpls. there’s no hiding behind a Tickets: $20, eTix.com. band here, and no doubting the meaning of the songs. and even “a lot of fun.” Just as “I’m lonely and tired/No surprisingly, he said he has no will left to fake it,” he sings qualms about playing these in “This House Is on Fire,” hard-fought songs live now, too. the album’s stark opening “A fter you work on songs as track. “You know it makes long and as hard as I did — and no sense/Where all the good it was longer than any album times went/This house is on I’ve ever worked on — you fire/A nd I’m not getting out.” kind of build up a tolerance Sitting near the unlit fire- to them, and the mechanics of place inside the house at the playing them kicks in more,” legendary Pachyderm Studio he said. “That’s the fun part.” in Cannon Falls two weeks He and the Dead Man Win- ago — a place that became a ter crew are ready to have more home away from home over fun. -

Ctba Newsletter 1104

1 COPYRIGHT © CENTRAL TEXAS BLUEGRASS ASSOCIATION IBMA Member Central Vol. 33 No. 4 Texas Bluegrass Apr 1, 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Central Texas Bluegrass Association Has Anybody Seen any Old Settlers ‘round Here I hope you have your rubber boots and waders...it’s time again for Old Set- tler’s Music Festival. It seems the past few years the festival has had more than its share of “April Show- ers”. Shucks, the rain doesn’t stop the pick- ing and the live music. The 2011 lineup includes The Avett Brothers, The Richard Thompson Electric Trio, Sam Bush, Sonny Landreth, Tim O’Brien, E m m i t t - Nershi Band, The Gourds, Jimmy D a l e Gilmore with the Wronglers, Jake Shimabukuro, Lang- horne Slim, Band of Hea- thens, Foster & Lloyd, Trampled by Turtles, Gaelic Storm, Sahara Smith, Greensky Bluegrass, Audie Blaylock & Redline, Jim Lauderdale, David Francey, Green Mountain Grass, Elliott Brood, beatlegras, Ruby Jane, The Bridge, Dirtfoot, Warren Hood & the Goods, Suzanna Choffel, The Hillbenders, The Wayne- Billies, MilkDrive, Rose’s Pawn Shop, Youth Competition Winners Sarah Mueller and Minnie & Ella Jordan. Central Texas Bluegrass is once again co-sponsoring this event. Look for Ben Hodges in the CTBA tent. Buy a hat! See YOU there? 2 COPYRIGHT © CENTRAL TEXAS BLUEGRASS ASSOCIATION The Listening Post The Listening Post is a forum established to monitor bluegrass musical recordings, live performances, or events in Texas. Our mailbox sometimes contains CDs for us to review. Here is where you will find reviews of the CD’s Central Texas Bluegrass Association receives as well as reviews of live performances or workshops. -

DF19 Program Forweb.Pdf

WELCOME! Who is ready for our 12th annual family reunion? When we call DelFest a musical family, we mean it. This year isn’t any different from the first eleven DelFests, we just really wanted to draw attention to the fact that so many of these musicians are family to us. I’ve known Sam Bush for almost 50 years. Railroad Earth has played nine DelFests. The boys have toured a lot with Keller and Yonder Mountain. I’ve watched Sierra grow up. I’ve recorded a Larry Keel song. I’ve known the Gibson boys for 20+ years. And on and on. These folks are our family, and we hope that DelFest feels like we are all sitting on the front porch jamming. It doesn’t stop with the musicians. All of you fans are also our family. The staff of DelFest are family. The people of Cumberland have become family. Every year we get to come together and celebrate with all of you. For us, it really is like going to a family reunion. All that’s missing is the potluck dinner, so you’ll have to settle for some amazing food from our vendors, many who have been with us from year one – making them also family. So welcome to DelFest #12. We plan to have fun and hope you do too. Let’s treat each other like family (well, family that you like) and have a big ole time. We love you, we thank you, and we appreciate you. Del (and the entire McCoury Family) May 2019 3. -

Press Calendar of Events: Summer 2019

Press Calendar of Events: Summer 2019 Tickets for Wolf Trap’s 2019 Summer Season: Online: wolftrap.org By phone: 1.877.WOLFTRAP In person: Filene Center Box Office 1551 Trap Road | Vienna, Virginia 22182 Locations All performances held at the Filene Center (unless otherwise noted) 1551 Trap Road, Vienna, VA 22182 Select performances held at The Barns at Wolf Trap (noted on listing) 1635 Trap Road, Vienna, VA 22182 Media Information Please do not publish contact information. Emily Stout, Manager, Media Relations 703.255.4096 or [email protected] May 2019 The Avett Brothers Last appeared in 2018 Thursday, May 23 at 7:30 p.m. with openers: Rodney Crowell | Paleface Friday, May 24 at 7:30 p.m. with openers: Thao & The Get Down Stay Down | Paleface Saturday, May 25 at 7:30 p.m. Tickets $45-$75 with openers: The Felice Brothers | Paleface The Avett Brothers return to Wolf Trap by popular demand for a multi-night Americana rock retreat filled “with echoes of old-timey string bands, singalong folk revivalists, boozy Americana roots rockers and big-box singer – songwriter softies” (Rolling Stone). Sammy Hagar’s Full Circle Jam Tour* Featuring Michael Anthony, Vic Johnson & Jason Bonham Night Ranger Friday, May 31 at 8 p.m. Tickets $39.50-$89.50 The acclaimed supergroup featuring Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductees Sammy Hagar and bassist Michael Anthony, drummer Jason Bonham, and guitarist Vic Johnson, quickly established themselves as one of the most exciting live acts on tour today, seamlessly ripping through career-spanning hits from Montrose, Van Halen, Sammy Hagar and The Waboritas, Led Zeppelin, and new music from their 2019 album Space Between.