Itâ•Žs Not About the Clothes: Branding Strategies of American Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brooks Brothers Canada Ltd

1 Court File No. ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF BROOKS BROTHERS GROUP, INC., BROOKS BROTHERS FAR EAST LIMITED, BBD HOLDING 1, LLC, BBD HOLDING 2, LLC, BBDI, LLC, BROOKS BROTHERS INTERNATIONAL, LLC, BROOKS BROTHERS RESTAURANT, LLC, DECONIC GROUP LLC, GOLDEN FLEECE MANUFACTURING GROUP, LLC, RBA WHOLESALE, LLC, RETAIL BRAND ALLIANCE GIFT CARD SERVICES, LLC, RETAIL BRAND ALLIANCE OF PUERTO RICO, INC., 696 WHITE PLAINS ROAD, LLC, AND BROOKS BROTHERS CANADA LTD. APPLICATION OF BROOKS BROTHERS GROUP, INC. UNDER SECTION 46 OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, AS AMENDED APPLICANT APPLICATION RECORD September 13, 2020 OSLER, HOSKIN & HARCOURT LLP Box 50, 1 First Canadian Place Toronto ON M5X 1B8 Tracy Sandler (LSO# 32443N) Tel: 416.862.5890 Email: [email protected] Shawn T. Irving (LSO# 500035U) Tel: 416.862.4733 Email: [email protected] Martino Calvaruso (LSO# 57359Q) Tel: 416.862.6665 [email protected] Fax: 416.862.6666 Lawyers for the Applicant 2 ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF BROOKS BROTHERS GROUP, INC., BROOKS BROTHERS FAR EAST LIMITED, BBD HOLDING 1, LLC, BBD HOLDING 2, LLC, BBDI, LLC, BROOKS BROTHERS INTERNATIONAL, LLC, BROOKS BROTHERS RESTAURANT, LLC, DECONIC GROUP LLC, GOLDEN FLEECE MANUFACTURING GROUP, LLC, RBA WHOLESALE, LLC, RETAIL BRAND ALLIANCE GIFT CARD SERVICES, LLC, RETAIL BRAND ALLIANCE OF PUERTO RICO, INC., 696 WHITE PLAINS ROAD, LLC, AND BROOKS BROTHERS CANADA LTD. -

Spotlight Supima

AMERICAN GROWN | SUPERIOR | RARE | AUTHENTIC JUNE 2021 In This Edition Spotlight Supima PAGE 1 Joseph DeAcetis Spotlight Supima Forbes Contributing Editor ---------------------------- Marc Lewkowitz PAGE 2 Supima, President & CEO Weekly Export Summary “SUPIMA is 100% extra-long staple cotton in contrast to other well-known cotton labels such Supima and Albini Challenge as Egyptian or Pima. ® the Next Generation Today, Supima focuses on partnering with of Fashion Designers leading brands across fashion and home markets Gettees to ensure that consumers have access to and Get Cropped receive top quality products.” ---------------------------- PAGE 3 Daddy Dearest hat better way to tell the Father’s Day Guide story of Supima than through ---------------------------- the journalism of Forbes mag- PAGE 4 azine. Supima President and May Licensing Update CEO, Marc Lewkowitz recently sat down for an interview with ForbesW Contributing Editor Joseph DeAcetis. Covering a wide 100% of Supima cotton is mechanically harvested. range of topics from the history of Supima cotton to its unique traceability program, DeAcetis dives into why Supima cotton STAY CONNECTED is considered to be the top 1% of cotton grown around the world and the many relevant issues and challenges in today’s textile industry. America Has One Of The Best Luxury Cotton Grown In Every bale of Supima cotton has its length, The World strength and fineness classed by the USDA. Quite often, I like to highlight the great significance that the United States has on the world of fashion. When you think of all the developments created in our great nation such as the tuxedo, preppy, sportswear and even denim. -

Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines

Chair of Urban Studies and Social Research Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism Bauhaus-University Weimar Fashion in the City and The City in Fashion: Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines Doctoral dissertation presented in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) Maria Skivko 10.03.1986 Supervising committee: First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Frank Eckardt, Bauhaus-University, Weimar Second Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Stephan Sonnenburg, Karlshochschule International University, Karlsruhe Thesis Defence: 22.01.2018 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part I. Conceptual Approach for Studying Fashion and City: Theoretical Framework ........................ 16 Chapter 1. Fashion in the city ................................................................................................................ 16 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Fashion concepts in the perspective ........................................................................................... 18 1.1.1. Imitation and differentiation ................................................................................................ 18 1.1.2. Identity -

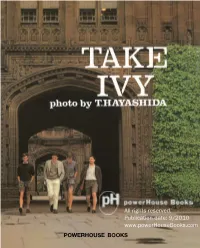

Take Ivy Was Originally Published Shosuke Ishizu Is the Representative Director in Japan in 1965, Setting Off an Explosion of of Ishizu Office

Teruyoshi Hayashida was born in the fashionable Aoyama District of Tokyo, where he also grew up. He began shooting cover images for Men’s Club magazine after the title’s launch. A sophisticated Photographs by Teruyoshi Hayashida dresser and a connoisseur of gourmet food, Text by Shosuke Ishizu, Toshiyuki Kurosu, he is known for his homemade, soy-sauce- and Hajime (Paul) Hasegawa marinated Japanese pepper (sansho), and his love of gunnel tempura and Riesling wine. Described by The New York Times as, “a treasure of fashion insiders,” Take Ivy was originally published Shosuke Ishizu is the representative director in Japan in 1965, setting off an explosion of of Ishizu Office. Originally born in Okayama American-influenced “Ivy Style” fashion among Prefecture, after graduating from Kuwasawa Design students in the trendy Ginza shopping district School he worked in the editorial division at Men’s of Tokyo. The product of four collegiate style Club until 1960 when he joined VAN Jacket Inc. enthusiasts, Take Ivy is a collection of candid He established Ishizu Office in 1983, and now photographs shot on the campuses of America’s produces several brands including Niblick. elite, Ivy League universities. The series focuses on men and their clothes, perfectly encapsulating Toshiyuki Kurosu was raised in Tokyo. He joined the unique student fashion of the era. Whether VAN Jacket Inc. in 1961, where he was responsible lounging in the quad, studying in the library, riding for the development of merchandise and sales bikes, in class, or at the boathouse, the subjects of promotion. He left the company in 1970 and Take Ivy are impeccably and distinctively dressed in started his own business, Cross and Simon. -

David Lynch Is Not Just One of the Most Important Filmmakers Working Today, He’S a Complete Artist

DAVID LYNCH is not just one of the most important filmmakers working today, he’s a complete artist. He writes songs, paints, makes sculptures, and even designs lamps, in the consistently odd, weirdly dreamy, but resilient style for which the adjective Lynchian has become a catchword. We met at Griffin Contemporary Art Gallery in Santa Monica, where an exhibition of Lynch’s recent paintings and sculptures filled the large, pristine white spaces, and asked him to talk about his enigmatic and ever-expanding personal universe. interview by ALEX ISRAEL portrait by ANNABEL MEHRAN All artworks photographed by Robert Wedemeyer, courtesy of William Griffin Gallery, Los Angeles alex israel — Tell me about your clothes. very inspiring for them. I think men would alex israel — Has David Lynch become Do wear the same thing every day? like it too. She talks about how important a character? david lynch — What I’m wearing now? grandmothers are. Everybody knows how david lynch — Everyone’s a character, No, no, I’m dressed up today. important grandmothers are, if they’re lucky in a way. enough to have one around. alex israel — I ask this because I read somewhere alex israel — Are you a character of your own that you wear the same thing every day. alex israel — If you do wear a suit, is it generally making — one from a David Lynch film? david lynch — I’m in a suit as I’m speaking a black suit? david lynch — In a way, yes. But I don’t to you, but I don’t wear one every day. -

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1957 A Rhetorical Study of the Gubernatorial Speaking of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Paul Jordan Pennington Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pennington, Paul Jordan, "A Rhetorical Study of the Gubernatorial Speaking of Franklin D. Roosevelt." (1957). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/222 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RHETORICAL STUD* OP THE GUBERNATORIAL SPEAKING OP FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Meohanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Speech by Paul Jordan Pennington B. A., Henderson State Teachers College, 19U8 M. A., Oklahoma University, 1950 August, 1957 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to acknowledge the inspiration, guidance, and continuous supervision of Dr. Waldo W. Braden, Professor of Speech at Louisiana State University. As the writer1s major advisor, he has given generously of his time, his efforts, and his sound advice. Dr. Braden is in no way responsible for any errors or short-comings of this study, but his suggestions are largely responsible for any merits it may possess. Dr. C. M. Wise, Head of the Department of Speech, and Dr. -

M a L L D I R E C T O

MALL DIRECTORY Coming to Eastview in 2013: www.eastviewmall.com 7979 Pittsford-Victor Road (Rte 96) Victor, NY 14564 MALL HOURS: ...more announcements coming soon! Monday - Saturday: 10:00 a.m. - 9:30 p.m. Sunday: 11:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. Holiday season hours vary. Stay up-to-date on what’s happening at Eastview! SECURITY: Find us on Follow us on (585) 223-2930 Lockouts • Escorts • Lost & Found CUSTOMER SERVICE CENTER: Located near Arby’s in the Food Court Scan to download the Eastview app to your (585) 223-4420 Droid or iPhone for the latest sales and deals, plus an interactive map of the mall. Or, Gift Cards • Rent a Stroller search Eastview Mall in your app store! Borrow a Wheelchair Gift Wrapping • Information Fees may apply . See back. G M W Style Card Mall gift card redeemable only LY Mall, Pittsford Plaza, at The Mall At Greece Ridge and Park Po , FOR ELECTRONICin USEt. ON Eastview, The Mar ketplace back. See Fees may apply rdD re CaGIFT CAR G ywhe WMAn 5555 8888LID 2200 1199 4 VA 527 THRU om rite.c .wilmo www The WMG Style Card is valid at participating stores at Eastview, The Mall at Greece Ridge, The Marketplace Mall, Pittsford Plaza and Park Point. The WMG Anywhere Card is valid anywhere LoveSac in the U.S that Mastercard is accepted. F ABERCROMBIE 223-6190 I CLAIRE’S ACCESSORIES 425-4050 J LEGO 223-9686 S SOLSTICE SUNGLASS P TOM WAHL’S 425-4860 I YOGEN FRÜZ 223-0220 I ABERCROMBIE & FITCH 223-4520 I CLARKS 223-6730 S LENSCRAFTERS 425-7400 BOUTIQUE 425-2180 K TOYS ‘R’ US EXPRESS 421-9874 K ZUMIEZ 425-8720 K AERIE 425-0394 E COACH 425-7720 P LIBERTY TRAVEL 425-2640 E SOMA INTIMATES 425-0752 A TUXEDO JUNCTION 223-3270 EASTVIEW SERVICES J AEROPOSTALE 425-4170 D COLDWATER CREEK 223-4750 L LIDS 223-4734 A SPENCER GIFTS 223-0330 E VERA BRADLEY 425-1829 P CUSTOMER SERVICE 223-4420 K ALDO 223-1577 A COLLECTOR’S PARADISE 223-3580 A LIMITED 223-5430 X STAPLES 425-8130 I VERIZON WIRELESS 223-9910 P MALL OFFICE 223-3693 N ALTIER’S SHOE DEPT. -

Catherina Gioino NYC's Gilded Age: Assignment 1 Brooks Brothers

Catherina Gioino NYC’s Gilded Age: Assignment 1 Brooks Brothers’ Gloves Basic Description: These brown, machine made leather gloves are dated to have been made between 1870 and 1900. The gloves measure to be about 9.5 inches in length and 4.25 inches in length. (To be exact, one glove measures 9.5 inches by 4.38 inches, and the other measures 9.62 inches by 4.25 inches). The men’s gloves each have a vertical slit at the bottom near the wrist and has a button with the words “Brooks” and “Brothers” written across the top and bottom of the button, respectively. Next to the button on the other side of the slit of the glove, there is a loop that will allow the wearer to notch the button through the glove and thus tighten the glove. Despite being over a century old, use or wear is very minimal, with a light fade on one of the gloves and a torn corner on the other. The gloves are very stiff as a result of its age and therefore there are rips in the gloves that otherwise would not be there save for the leather composition. There is a large chunk of broken leather on the faded stain glove, in the shape of a triangle, with each side about ¼- ½ an inch. The stitching of the glove with the corner falling off is wearing off, particularly around the thumb, as is the same with the fore and middle fingers of the other glove. Production: Although not much is known about the Brooks Brothers or the gloves in particular, it can be said that the gloves were most likely made in the Brooks Brothers’ store on Catherine and Cherry Streets in New York City, which was the first Brooks Brothers1 store after Henry Sands Brooks opens the store on the Northeast corner of those streets. -

First Report of the Information Officer

Court File No. CV-20-00647463-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C 36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF BROOKS BROTHERS GROUP, INC., BROOKS BROTHERS FAR EAST LIMITED, BBD HOLDING 1, LLC, BBD HOLDING 2, LLC, BBDI, LLC, BROOKS BROTHERS INTERNATIONAL, LLC, BROOKS BROTHERS RESTAURANT, LLC, DECONIC GROUP LLC, GOLDEN FLEECE MANUFACTURING GROUP, LLC, RBA WHOLESALE, LLC, RETAIL BRAND ALLIANCE GIFT CARD SERVICES, LLC, RETAIL BRAND ALLIANCE OF PUERTO RICO, INC., 696 WHITE PLAINS ROAD, LLC, AND BROOKS BROTHERS CANADA LTD. APPLICATION OF BROOKS BROTHERS GROUP, INC. UNDER SECTION 46 OF THE COMPANIES' CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 19850 c. C-36, AS AMENDED FIRST REPORT OF THE INFORMATION OFFICER ALVAREZ & MARSAL CANADA INC. September 23, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND DISCLAIMER ....................................................................... 4 3.0 PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT ................................................................................................... 6 4.0 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ 7 5.0 ALL ORDERS ORDER .............................................................................................................. 15 6.0 THE SALE TRANSACTION .................................................................................................... -

101 CC1 Concepts of Fashion

CONCEPT OF FASHION BFA(F)- 101 CC1 Directorate of Distance Education SWAMI VIVEKANAND SUBHARTI UNIVERSITY MEERUT 250005 UTTAR PRADESH SIM MOUDLE DEVELOPED BY: Reviewed by the study Material Assessment Committed Comprising: 1. Dr. N.K.Ahuja, Vice Chancellor Copyright © Publishers Grid No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduce or transmitted or utilized or store in any form or by any means now know or here in after invented, electronic, digital or mechanical. Including, photocopying, scanning, recording or by any informa- tion storage or retrieval system, without prior permission from the publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by Publishers Grid and Publishers. and has been obtained by its author from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the publisher and author shall in no event be liable for any errors, omission or damages arising out of this information and specially disclaim and implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Published by: Publishers Grid 4857/24, Ansari Road, Darya ganj, New Delhi-110002. Tel: 9899459633, 7982859204 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Printed by: A3 Digital Press Edition : 2021 CONTENTS 1. Introduction to Fashion 5-47 2. Fashion Forecasting 48-69 3. Theories of Fashion, Factors Affecting Fashion 70-96 4. Components of Fashion 97-112 5. Principle of Fashion and Fashion Cycle 113-128 6. Fashion Centres in the World 129-154 7. Study of the Renowned Fashion Designers 155-191 8. Careers in Fashion and Apparel Industry 192-217 9. -

Brooks Brothers' Ap Team

WEBINAR Presenters Sarah Fane Peter Gerardi Joe Hanousek Operational Accounting Head of Research Customer Experience sharedserviceslink Manager Brooks Brothers Manager Esker Questions • Send me your question early • Use this opportunity to get the answers/info you seek • The sooner you send me the question, the more likely it will be asked • Remember to stay on for Q&A in the last 10 minutes of the session Your copy of the slides The slides will be available after the webinar at www.sharespace.digital AgendaAgenda • Intro and Context • Poll question • Drivers for change at Brooks Brothers • Insight into the implementation • Results and lessons learned • About Esker AgendaContext Before automating, Brooks Brothers’ Accounts Payable process was about as manual as you can get. To improve their processes, Brooks Brothers implemented Esker’s automation software and SAP at the same time. Today we will explore how they • Dramatically improved visibility at the supplier service levels • Reduced manual data entry which was costly and inefficient • Eased month-end and year-end closing challenges • Improved invoice receipt to posting cycle time Learn how they modernized and digitized AP and how they have achieved FTE savings and how they have been able to expand with the business without adding headcount. Poll questions Where are you on your AP automation journey? • Looking to further automate AP in the next 12 months • Looking to further automate AP in the next 24 months • Looking to expand or improve our e-invoicing program • We are happy with our current levels of automation HOW BROOKS BROTHERS AUTOMATED AP TODAY’S SPEAKER PETE GERARDI Manager, Operational Accounting Brooks Brothers BROOKS BROTHERS COMPANY OVERVIEW AMERICA’S OLDEST CLOTHING RETAILER 1818 400 20 FOUNDED STORES IN COUNTRIES OPERATION WORLDWIDE EMEA • Owned (Europe; UK); Distributor (Greece) • $49M Est. -

Tommy Hilfiger, Renowned Designer Known for Preppy American

Contact: Debbie Goldberg Director of Media Relations 215.951.2718 News [email protected] Tommy Hilfiger, renowned designer known for preppy American sportswear style, will receive the 2011 Spirit of Design Award at the Philadelphia University Fashion Show Philadelphia University’s Fashion Show will take place Saturday, April 30, 2011 at the Academy of Music as part of an Evening of Innovation PHILADELPHIA, Jan. 18, 2011— Tommy Hilfiger, who for 25 years has been at the forefront of the classic but trendy all-American preppy look, will receive the prestigious 2011 Spirit of Design Award at Philadelphia University’s Fashion Show on Saturday, April 30, at the Academy of Music. Hilfiger, a self-taught designer known for casual styles and his classic red, white and blue flag logo, is an American fashion icon who oversees a brand that includes men’s, women’s and children’s apparel, sportswear, denim, and a range of licensed products such as accessories, fragrances and home furnishings. There are more than 1,000 Tommy Hilfiger stores worldwide and in 2008 the company announced an exclusive partnership with Macy’s to sell its sportswear in the U.S. “I am very honored to receive the Philadelphia University Spirit of Design Award,” Tommy Hilfiger said. “I think it is incredibly important to give back and to support new designers interested in working in the fashion industry.” “We are thrilled that Tommy Hilfiger is the 2011 recipient of the Philadelphia University Spirit of Design Award,” said Clara Henry, director of Philadelphia University’s fashion design program. “He is an international fashion icon who is an advocate for design education and nurturing young talent.” --more— Philadelphia University/ page 2 The Tommy Hilfiger brand is centered around a hip and colorful button-down, casual lifestyle.