Toccata Classics TOCC 0025 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking the Dynamics of Music and Nationalism

Rethinking the Dynamics of Music and Nationalism University of Amsterdam, 26-29 September 2017 Conference Booklet Organizational committee: Prof. dr. Joep Leerssen, Professor of Modern European Literature, University of Amsterdam dr. Kasper van Kooten, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Amsterdam 1 Table of Contents: Schedule p. 3 Abstracts p. 10 Practical Information p. 44 2 Schedule: Tuesday 26 September Opening of Conference Location: Vlaams Cultuurhuis De Brakke Grond, Nes 45, 1012 KD Amsterdam (close to Dam Square) 18.30 Registration, coffee and tea 19.00 Kasper van Kooten, Postdoctoral research fellow, Modern European Literature, University of Amsterdam – Welcome and introduction 19.05 Katharine Ellis, Professor of Music, University of Cambridge – Nationalism, Ethnic Nationalism, and the Third Republic’s Folk Music Problem 19.50 Joep Leerssen, Professor of Modern European Literature, University of Amsterdam – The Persistence of Voice: Instrumental Music and Romantic Orality of the Late John Neubauer (1933-2015) 20.10 Krisztina Lajosi-Moore, Assistant Professor in Modern European Literature and Culture, University of Amsterdam, and Kasper van Kooten – Opera and National Identity-Articulation in Germany and Hungary 20.30 – 21.15 Audience questions and panel discussion – The Outer Edges of National-Classical Music: Territory, Society, Tradition 21.15 - 22.00 Drinks 3 Wednesday 27 September Location: De Rode Hoed, Cultureel Centrum, Keizersgracht 102, 1015 CV Amsterdam Room: Vrijburgzaal Banningzaal 09.00-10.00 Keynote: Graeme -

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Summer Quarter 2019 (July - September) A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

Antonín Dvořák and the Concept of Czechness

11 /1 hen the Czechoslovak Republic was born in 1918, fairly fresh on the market were the first books devoted entirely to Antonín Dvořák—all ofW which gave prominent attention to his ‘Czechness’. First came a compendium of essays by various authors published by the Umělecká beseda (Artists’ Society) in Prague in 1912.1 Here we find e.g. Emanuel Chvála writ- ing about the symphonic works: In contemporary worldwide symphonic literatu- re the symphonies of Dvořák are distinguished Con tempo diverso / Vzdálená blízkost společného (Praha, 30.-31 mainly by their national coloring, there explicit David R. BEvEridge Czechness. [...] (Prague) [...] Dvořák’s merit and his success in sympho- nies is that he filled the existing and established form, which he took as he found it, with new content, with his own music, permeated with Antonín Dvořák and Czechness—music healthy, original, and natural.2 the Concept of Czechness And in an essay on the piano music Karel Hoffmeister tells us: 1 Antonín Dvořák: Sborník statí o jeho díle a životě [ed. Bole- slav K ALENSKÝ] (Prague: Umělecká beseda, 1912). 2 Ibid., pp. 130, 133: V soudobé světové tvorbě symfonické vyznačují se symfonie Dvořákovy hlavně svojí národní barvou, svojí vyslovenou čes- kostí. [...] [...] Dvořákovou zásluhou a jeho úspěchem v symfonii jest, že stávající a ustálenou formu, již vzal tak, jak ji nalezl, naplnil obsahem novým, svojí vlastní, českostí proniknutou, zdravou, původní a přirozenou hudbou. ABSTRACT When the Czechoslovak Republic was born in 1918, fairly As concerns Czech patriotism, Dvořák was not nearly so fresh on the market were the first books devoted entirely fanatical as many of his countrymen were at the time. -

Rehearsal and Concert

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON cS^MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES .„„v j Ticket Office, 1492 ) , ^ ^^ „ TelephonesT, ^^^^ ^^^„ j Administration Offices, 3200 } THIRTIETH SEASON, 1910 AND 1911 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor Programme of % Eighteenth Rehearsal and Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON, MARCH 10 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, MARCH 11 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHJ, 1910, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A.ELLIS, MANAGER 1317 WM. L. WHITNEY International School for Vocalists BOSTON NEW YORK SYMPHONY CHAMBERS 134 CARNEQIE HALL 246 HUNTINGTON AVE. CORNER OF S7th AND 7th AVE. PORTLAND HARTFORD Y. M. C. A. BUILDING HARTFORD SCHOOL OF MUSIC CONGRESS SQUARE 8 SPRING STREET 1318 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL Thirtieth Season, 1910-1911 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor Violins. WItek. A., Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Ctmcert-maiter. Kuntz, D. Krafft, F. W. Noack, S. ^UUJXlXJX!.UJJJiXl^^ Perfection m Piano Making 5 feet long THE -€f<^imxxn Quarter Grand Style V, in figured MaKogany, price ^650 It IS Dut five reet long ana m Tonal Proportions a Masterpiece or piano builcling. It IS Cnickering & Sons most recent triumpli, tke exponent oi EIGHTY-SEVEN YEARS experience m artistic piano building, and tne neir to all the qualities tliat tke name oi its makers implies. CHICKERING ^ SONS Established 1823 791 TREMONT STREET. Comet Northampton Street, near Mass. Ave. BOSTON >n« in< mum imvx tm uwmm vm v^wv yw tn« iftiwv» iaiiai tA< >a<vwiiify g I THIRTIETH SEASON, NINETEEN HUNDRED TEN AND ELEVEN lEtglff^mtlj S^If^arsal anJn (Hcntnt FRIDAY AFTERNOON, MARCH 10, at 2.30 o'clock SATURDAY EVENING, MARCH H, at 8 o'clock PROGRAMME Brahms ..... -

The New York Chamber Music Society, 1915-1937: a Contribution to Wind Chamber Music and a Reflection of Concert Life in New York City in the Early 20Th Century

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2013 The New York Chamber Music Society, 1915-1937: A Contribution to Wind Chamber Music and a Reflection of Concert Life in New York City in the Early 20th Century Lisa Kozenko The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2557 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The New York Chamber Music Society, 1915-1937: A Contribution to Wind Chamber Music and a Reflection of Concert Life in New York City in the Early 20th Century by LISA A. KOZENKO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2013 © 2013 Lisa A. Kozenko All rights reserved. This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Professor Jeffrey Taylor ___________________ ________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor David Olan ___________________ ________________________ Date Executive Officer Professor Richard Burke Professor Sylvia Kahan Professor Catherine Coppola Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Abstract The New York Chamber Music Society, 1915-1937: A Contribution to Wind Chamber Music and a Reflection of Concert Life in New York City in the Early 20th Century by Lisa A. -

Concerts Including Music of Anton Bruckner (1900-2015)

« Wiener Symphoniker » : Concerts including music of Anton Bruckner (1900-2015) (The « repeat » concerts are included in the list.) Original source : http://www.wienersymphoniker.at/concerts/saison/archiv 1900 : 2 1901 : 2 1902 : 4 1903 : 7 1904 : 9 1905 : 3 1906 : 8 1907 : 6 1908 : 12 1909 : 11 1910 : 25 1911 : 20 1912 : 12 1913 : 15 1914 : 10 1915 : 18 1916 : 10 1917 : 12 1918 : 12 1919 : 13 1920 : 14 1921 : 18 1922 : 18 1923 : 16 1924 : 18 1925 : 15 1926 : 18 1927 : 13 1928 : 16 1929 : 17 1930 : 13 1931 : 20 1932 : 11 1933 : 14 1934 : 12 1935 : 18 1936 : 21 1937 : 13 1938 : 12 1939 : 20 1940 : 19 1941 : 11 1942 : 22 1943 : 24 1944 : 6 1945 : 0 1946 : 9 1947 : 16 1948 : 12 1949 : 14 1950 : 15 1951 : 15 1952 : 12 1953 : 23 1954 : 17 1955 : 20 1956 : 8 1957 : 14 1958 : 19 1959 : 15 1960 : 8 1961 : 20 1962 : 22 1963 : 14 1964 : 11 1965 : 22 1966 : 8 1967 : 6 1968 : 5 1969 : 20 1970 : 16 1971 : 19 1972 : 14 1973 : 18 1974 : 15 1975 : 7 1976 : 7 1977 : 13 1978 : 8 1979 : 4 1980 : 18 1981 : 22 1982 : 12 1983 : 13 1984 : 14 1985 : 4 1986 : 6 1987 : 24 1988 : 9 1989 : 4 1990 : 6 1991 : 6 1992 : 8 1993 : 15 1994 : 34 1995 : 1 1996 : 9 1997 : 7 1998 : 18 1999 : 16 2000 : 4 2001 : 14 2002 : 0 2003 : 16 2004 : 12 2005 : 3 2006 : 6 2007 : 3 2008 : 13 2009 : 5 2010 : 3 2011 : 3 2012 : 13 2013 : 11 2014 : 5 2015 : 13 Chief Conductors of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra Ferdinand Löwe (1900-1925) . -

Riccardo Muti Conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti

Program ONe huNdred TweNTy-FirST SeASON Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez helen regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 6, 2011, at 8:00 Friday, October 7, 2011, at 1:30 Saturday, October 8, 2011, at 8:30 riccardo muti conductor gerhard oppitz piano Sinigaglia Overture to Le baruffe chiozzotte, Op. 32 mendelssohn Symphony No. 4 in A Major, Op. 90 (Italian) Allegro vivace Andante con moto Con moto moderato Saltarello: Presto IntermISSIon martucci Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Minor, Op. 66 Allegro giusto Larghetto Finale: Allegro con spirito GerhArd OPPiTz Busoni Berceuse élégiaque Bossi Intermezzi Goldoniani, Op. 127 Preludio e Minuetto Gagliarda Serenatina Burlesca Thursday evening’s concert is supported in part through the generosity of the Julius N. Frankel Foundation. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommentS By PhiLLiP huSCher mahler’s Last Concert to honor the CentenarY of guStav mahLer’S death, rICC ardo mutI and the ChIC ago SYmPhonY Perform the LaSt Program mahLer ConduCted n Tuesday, February 21, 1911, Gustav Mahler ignored his Odoctor’s advice to cancel that evening’s “Italian” program with the New York Philharmonic, wrapped himself in thick wool clothing, and set out with his wife Alma from the Savoy Hotel to nearby Carnegie Hall. He had led the previous day’s rehearsal with a sore throat and a high fever. The players later remembered only that he cut the rehearsal short, saying that they weren’t really ready, but that he didn’t want to keep them too long. -

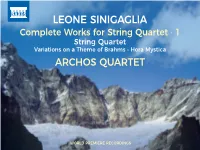

LEONE SINIGAGLIA Complete Works for String Quartet · 1 String Quartet Variations on a Theme of Brahms • Hora Mystica ARCHOS QUARTET

LEONE SINIGAGLIA Complete Works for String Quartet · 1 String Quartet Variations on a Theme of Brahms • Hora Mystica ARCHOS QUARTET WORLD PREMIERE RECORDINGS Leone ¡ Scherzo, Op. 8 (1892) ..........................................................................................................................3:32 SINIGAGLIA ™ Hora Mystica (1890) ............................................................................................................................ 2:49 (1868–1944) Complete Works for String Quartet · 1 String Quartet in D major, Op. 27 (1902) ............................................................................ 32:17 £ I. Allegro comodo .........................................................................................................................................9:04 1 Concert-Étude in D major, Op. 5 (pub. c. 1901) ....................................................... 6:21 ¢ II. Scherzo: Allegro vivo .............................................................................................................................. 7:08 ∞ III. Adagio non troppo ..................................................................................................................................8:36 § IV. Allegro con spirito .................................................................................................................................. 7:29 Zwei Characterstücke, Op. 35 (version for string quartet) (pub. 1910) ................. 9.11 2 Regenlied (‘Rain Song’) ............................................................................................................................. -

Wind Music Cds (PDF)

CWU MUSIC LIBRARY WIND DISCOGRAPHY (ON CD) Updated November 28, 2012 First Edition: STACIE KUDAMATSU Second Edition: CHRISTINE JOLLEY Third Edition: CARYN WRZESINSKI Fourth Edition: JEFF VOGEL Fifth Edition: BIRKIN OWART Sixth Edition: KELSEY WEBER, GUS LABAYEN, HEATHER GLIKFELD Seventh Edition: GUS LABAYEN A.) MIXED WINDS G.) CORNET/ TRUMPET (p.135) B.) FLUTE (p. 56) H.) HORN (p. 148) C.) OBOE (p. 88) I.) TROMBONE (p.166) D.) CLARINET (p. 97) J.) BARITONE/ EUPHONIUM (p.179) E.) BASSOON (p.118) K.) TUBA (p. 188) F.) SAXOPHONE (p. 127) A.) MIXED WINDS CD-3878 6 SONATE A DUE HAUTBOIS ET BASSON ZELENKA: Sonata No. 1 in F major, ZELENKA: Sonata No. 2 in G minor, ZELENKA: Sonata No. 3 in B flat major ZELENKA: Sonata No. 4 in G minor, ZELENKA: Sonata No. 5 in F major, ZELENKA: Sonata No. 6 in C minor CD-1368 THE AIR FORCE BAND OF THE MIDWEST: Aiming High. BARRICK: Don't Have to Try. BERLIN: Blue Skies. CATINGUB: Battle of the Bop Brothers. FLORENCE: Only You. FUCIK: Florentiner March. GOODWIN: Those Magnificent Men. HANKINS: Bluegrass of Kentucky. Our Lives are Changing. HANKINS/ STEVENS: Burn the Bridge. HENLEY/ SILBAR: Wind Beneath My Wings. McCARTHY: Interlochen Fanfare. McHUGH/ KOEHLER: Aiming High. RODGERS: Falling In Love with You. SCHEIDT: The Battle. UNKNOWN: Everyday, I Have the Blues. I Dig Rock and Roll Music. St. James Infirmary. WILLIAMS: Air Force Time. CD-1367 THE AIR FORCE BAND OF THE MIDWEST: An Evening In ` December. ANDERSON: Sleigh Ride. BEAL/ BOOTHE MARKS: Jingle Bell Rockin'. BERLIN: White Christmas. DAVIS: Traditions of Christmas. -

Opere Per Oboe E Pianoforte Tra Ottocento E Novecento

DONIZETTI · GARIBOLDI · BOLZONI SGAMBATI · SINIGAGLIA· LONGO ZANELLA · ROTA Opere per oboe e pianoforte tra Ottocento e Novecento LUCIANO FRANCA · FILIPPO PANTIERI 850002_Booklet.indd 1 18/11/15 10:37 Tactus Termine latino con il quale, in epoca rinascimentale, si indicava quella che oggi è detta «battuta». The Renaissance Latin term for what is now called a measure. 2016 Tactus s. a. s. di℗ Gian Enzo Rossi & C. www.tactus.it In copertina / Cover: Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774-1840). Sunset (Brothers), ca. 1835. Si ringraziano: l’Amministrazione Comunale di Montefiore Conca (RN) per l’utilizzo del Teatro Malatesta; l’Associazione musicale no profit «Accademici Italiani» per la collaborazione nelle ricerche delle partiture; Flavio Liberalon per il noleggio del pianoforte; la Prof.ssa Marta Mancini per le note musicologiche allegate. 24 bit digital recording Tecnico del suono, editing: Luigi Faggi Grigioni Mastering: Davide Battistelli English Translation: Marta Innocenti L’editore è a disposizione degli aventi diritto. 850002_Booklet.indd 2 18/11/15 10:37 LUCIANO FRANCA Già Primo Oboe presso l’Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala, continua a collaborare con prestigiose Orchestre Lirico-Sinfoniche. Attivissimo in ambito solistico e cameristico ha effettuato tourneè in Germania, Francia, Spagna, Sudamerica, Paesi Arabi. Direttore Artistico dell’Associazione Accademici Italiani cura revisioni di brani inediti per Oboe, per Corno Inglese e per Ensemble di Fiati. Ha al suo attivo diverse registrazioni discografiche. Docente di Oboe presso -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Fall Quarter 2019 (October - December) A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more.