A Fresh Perspective on Rita Angus's Self-Portraits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Identity Portrait Unit

Cultural Identity Portrait Unit Drawing and Painting Level 4*, Year 9 This resource is offered as an example of a unit that engages with the “front end” of The New Zealand Curriculum (2007) – considering Vision, Principles, Values, and Key Competencies, as well as Achievement Objectives. *Teachers are encouraged to use or modify this work in any way they find helpful for their programmes and their students. For example, it may be inappropriate to assess all students at level 4. UNIT: Cultural Identity Portrait CURRICULUM LEVEL: 4 MEDIA: Drawing and Painting YEAR LEVEL: 9 DURATION: Approximately 16 – 18 Periods ASSESSMENT: Tchr & Peer DESCRIPTION OF UNIT Students research and paint a self-portrait that demonstrates an understanding of the Rita Angus work ‘Rutu’. CURRICULUM LINKS VISION: Confident – producing portraits of themselves that acknowledge elements of their cultural identity will help students to become confident in their own identity. Connected – working in pairs and small groups enables students to develop their ability to relate well to others. Producing a portrait which incorporates a range of symbols develops students’ abilities as effective users of communication tools. Lifelong learners – comparing traditional and contemporary approaches to painting portraits helps students to develop critical and creative thinking skills. PRINCIPLES: High Expectations – there are near endless opportunities for students to strive for personal excellence through the production of a self-portrait: students are challenged to make art works that clearly represent themselves both visually and culturally. Cultural diversity – students are introduced to portraits showing a range of cultures. They are required to bring aspects of their own cultural identity to the making of the portrait, and share these with other members of their class. -

Ascent03opt.Pdf

1.1.. :1... l...\0..!ll1¢. TJJILI. VOL 1 NO 3 THE CAXTON PRESS APRIL 1909 ONE DOLLAR FIFTY CENTS Ascent A JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND The Caxton Press CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND EDITED BY LEO BENSEM.AN.N AND BARBARA BROOKE 3 w-r‘ 1 Published and printed by the Caxton Press 113 Victoria Street Christchurch New Zealand : April 1969 Ascent. G O N T E N TS PAUL BEADLE: SCULPTOR Gil Docking LOVE PLUS ZEROINO LIMIT Mark Young 15 AFTER THE GALLERY Mark Young 21- THE GROUP SHOW, 1968 THE PERFORMING ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND: AN EXPLOSIVE KIND OF FASHION Mervyn Cull GOVERNMENT AND THE ARTS: THE NEXT TEN YEARS AND BEYOND Fred Turnovsky 34 MUSIC AND THE FUTURE P. Plat: 42 OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER 47 JOHN PANTING 56 MULTIPLE PRINTS RITA ANGUS 61 REVIEWS THE AUCKLAND SCENE Gordon H. Brown THE WELLINGTON SCENE Robyn Ormerod THE CHRISTCHURCH SCENE Peter Young G. T. Mofi'itt THE DUNEDIN SCENE M. G. Hire-hinge NEW ZEALAND ART Charles Breech AUGUSTUS EARLE IN NEW ZEALAND Don and Judith Binney REESE-“£32 REPRODUCTIONS Paul Beadle, 5-14: Ralph Hotere, 15-21: Ian Hutson, 22, 29: W. A. Sutton, 23: G. T. Mofiifi. 23, 29: John Coley, 24: Patrick Hanly, 25, 60: R. Gopas, 26: Richard Killeen, 26: Tom Taylor, 27: Ria Bancroft, 27: Quentin MacFarlane, 28: Olivia Spencer Bower, 29, 46-55: John Panting, 56: Robert Ellis, 57: Don Binney, 58: Gordon Walters, 59: Rita Angus, 61-63: Leo Narby, 65: Graham Brett, 66: John Ritchie, 68: David Armitage. 69: Michael Smither, 70: Robert Ellis, 71: Colin MoCahon, 72: Bronwyn Taylor, 77.: Derek Mitchell, 78: Rodney Newton-Broad, ‘78: Colin Loose, ‘79: Juliet Peter, 81: Ann Verdoourt, 81: James Greig, 82: Martin Beck, 82. -

Bulletin Autumn Christchurch Art Gallery March — May B.156 Te Puna O Waiwhetu 2009

Bulletin Autumn Christchurch Art Gallery March — May B.156 Te Puna o Waiwhetu 2009 1 BULLETIN EDITOR Bulletin B.156 Autumn DAVID SIMPSON Christchurch Art Gallery March — May Te Puna o Waiwhetu 2009 GALLERY CONTRIBUTORS DIRECTOR: JENNY HARPER CURATORIAL TEAM: KEN HALL, JENNIFER HAY, FELICITY MILBURN, JUSTIN PATON, PETER VANGIONI PUBLIC PROGRAMMES: SARAH AMAZINNIA, LANA COLES PHOTOGRAPHERS: BRENDAN LEE, DAVID WATKINS OTHER CONTRIBUTORS ROBBIE DEANS, MARTIN EDMOND, GARTH GOULD, CHARLES JENCKS, BRIDIE LONIE, RICHARD MCGOWAN, ZINA SWANSON, DAVID TURNER TEL: (+64 3) 941 7300 FAX: (+64 3) 941 7301 EMAIL: [email protected], [email protected] PLEASE SEE THE BACK COVER FOR MORE DETAILS. WE WELCOME YOUR FEEDBACK AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE ARTICLES. CURRENT SUPPORTERS OF THE GALLERY AALTO COLOUR CHARTWELL TRUST CHRISTCHURCH ART GALLERY TRUST COFFEY PROJECTS CREATIVE NEW ZEALAND ERNST & YOUNG FRIENDS OF CHRISTCHURCH ART GALLERY GABRIELLE TASMAN HOLMES GROUP HOME NEW ZEALAND LUNEYS PHILIP CARTER PYNE GOULD CORPORATION SPECTRUM PRINT STRATEGY DESIGN & ADVERTISING THE PRESS THE WARREN TRUST UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY FOUNDATION VBASE WARREN AND MAHONEY Visitors to the Gallery in front of Fiona Hall’s The Price is Right, installed as part of the exhibition Fiona Hall: Force Field. DESIGN AND PRODUCTION ART DIRECTOR: GUY PASK Front cover image: Rita Angus EDITORIAL DESIGN: ALEC BATHGATE, A Goddess of Mercy (detail) 1945–7. Oil on canvas. Collection CLAYTON DIXON of Christchurch Art Gallery Te PRODUCTION MANAGER: -

Exhibitions & Events at Auckland Art Gallery Toi O

Below: Michael Illingworth, Man and woman fi gures with still life and fl owers, 1971, oil on canvas, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki MARITIME MUSEUM FERRY TERMINAL QUAY ST BRITOMART On Show STATION EXHIBITIONS & EVENTS CUSTOMS ST BEACH RD AT AUCKLAND ART GALLERY TOI O TĀMAKI FEBRUARY / MARCH / APRIL 2008 // FREE // www.aucklandartgallery.govt.nz ANZAC AVE SHORTLAND ST HOBSON ST HOBSON ALBERT ST ALBERT QUEEN ST HIGH ST PRINCES ST PRINCES BOWEN AVE VICTORIA ST WEST ST KITCHENER LORNE ST LORNE ALBERT PARK NEW MAIN WELLESLEY ST WEST STANLEY ST GALLERY GALLERY GRAFTON RD WELLESLEY ST AUCKLAND AOTEA R MUSEUM D SQUARE L A R O Y A M Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki Discount parking - $4 all day, weekends and PO Box 5449, Auckland 1141 public holidays, Victoria St carpark, cnr Kitchener New Gallery: Cnr Wellesley and Lorne Sts and Victoria Sts. After parking, collect a discount voucher from the gallery Open daily 10am to 5pm except Christmas Day and Easter Friday. Free guided tours 2pm daily For bus, train and ferry info phone MAXX Free entry. Admission charges apply for on (09) 366 6400 or go to www.maxx.co.nz special exhibitions The Link bus makes a central city loop Ph 09 307 7700 Infoline 09 379 1349 www.stagecoach.co.nz/thelink www.aucklandartgallery.govt.nz ARTG-0009-serial Auckland Art Gallery’s main gallery will be closing for development on Friday 29 February. Exhibitions and events will continue at the New Gallery across the road, cnr Wellesley & Lorne sts. On Show Edited by Isabel Haarhaus Designed by Inhouse ISSN 1177-4614 Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki relies on From the Chris Saines, the good will and generosity of corporate Gallery Floor Plans partners. -

About People

All about people RYMAN HEALTHCARE ANNUAL REPORT 2019 We see it as a privilege to look after older people. RYMAN HEALTHCARE 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 04 Chair’s report 12 Chief executive’s report 18 Our directors 20 Our senior executives 23 How we create value over time 35 Enhancing the resident experience 47 Our people are our greatest resource 55 Serving our communities 65 The long-term opportunities are significant 75 We are in a strong financial position 123 We value strong corporate governance 3 RYMAN HEALTHCARE CHAIR’S REPORT We continue to create value 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 RYMAN HEALTHCARE CHAIR Dr David Kerr Ryman has been a care company since it started 35 years ago. As we continue to grow, we continue to create value for our residents and their families, our staff, and our shareholders by putting care at the heart of everything we do. We’re a company with a purpose – to look after older people. We know that if we get our care and resident experience right, and have happy staff, the financial results take care of themselves. I believe purpose and profitability are comfortable companions. Integrating the two supports us in creating value over time. This year, we continue to use the Integrated Reporting <IR> Framework* to share the wider story of how we create that value. *For more information on the <IR> Framework, visit integratedreporting.org 5 RYMAN HEALTHCARE “I believe purpose As a company we’re very focused on growth, but we will not compromise our core value of and profitability are putting our residents first. -

Five New Zealand Watercolou Rists

FIVE NEW ZEALAND WATERCOLOU RISTS NOV-DEC, 1958 I N T R O D U C T I O N i i:x i! 11:1 i II>N ttA8 r.r.i \ M;I; \.\H.U) in ivprfsent tisK vvlii.v [niniip.il iiK'dimn • is \vatcrcol(.tur. !ou>' lias been used to ,1 onisidi i.iiik- r.vti-m in :\rv, /_-. i ! i ir.u'ilnu ft -n ihc early i , at • . h .uui IIL-LLIUSI' :: tli ••. ! be , inec and ii i-in iis ;iji|tlii.-,iiii n than in li attists in this exhitilioin — frorh (.'hristchurch, VVeU ' : 'ul and ' ' i ' ill v -'I u n and ;i !c\\ h;!\f hcxn i_'\hilii:inu |',M n;.:ii\ \LVIIS. ! in.' c\i.iNl«. n >'.iii in nu -,', I . icd u'trnsjK-ttivf Hi' cxluiustivc in selection as .ill tin- artisU iiasv hccn Jihc. 1>. A. TO MO it I' .xoTi:: All ;': fjl .. '' I '.,,,, : . '' Oft, lire in inches, height before i> Lvqiiiries concerning purcnalei should m to the artist concerned through the Auckli: THE CATALOGUE RITA ANGUS 1 \VAIKANAE 184 x 14 Signed and dated Rita Angus '51. 2 MANGOMII Mix 15| Signed and dated Rita Angus '55. 3 KA1KOURA LANDSCAPE i5Jx22J Signed and dated Rita Angus '56 4 WESTSHORE, NAPIER £»x.22| Signed and dated Rita Angus '5/ 5 IRISES 22Sxl5j{ Signed and dated Rita Angus '58 *• 6 FUNGI 10{-xl4i Signed Rita Angus 7 MOUNT CAMEL 8} x 10i Signed Rita Angus 8 SUMMER 1 ! .x 14 Signed Rita Angus OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER 9 I LOWERS 18x23 Signed O/ii-ii< Spencer Boiver 10 CAMPING PLACE 12}xl5A Signed O/IIKJ Spencer Bower 11 TOKLESSE RANGE' BixK,l Signed Oliriti Spencer Bower 12 MOUNT PLENTY Hixl61 Sixncd Olivia Spencer Bower 13 NEAR QUELNSTOWN 13 x 17£ Signed Olivia Spencer Bou'cr 14 WET DAY, QUEENSTOWN -

NCEA Level 2 Art History (90228) 2011 Assessment Schedule

NCEA Level 2 Art History (90228) 2011 — page 1 of 4 Assessment Schedule – 2011 Art History: Examine subjects and themes in art (90228) Evidence Statement Question One: Māori Art / Taonga Achievement Achievement with Merit Achievement with Excellence For EACH of the two works: As for Achievement, plus: As for Merit, plus: Describes ONE key aspect of the Explains how the subject matter is Evaluates the significance of the subject matter. used to convey these themes / themes / ideas in Māori art. AND ideas. Explains the themes or ideas presented in EACH painting. Responses could include: Responses could include: Responses could include: Arnold Manaaki Wilson, Ode to Arnold Wilson uses his sculpture to Care of the natural resources of Tane Mahuta refer to traditional Māori use of New Zealand has been a big Subject timber for carving the sculptures that concern for many people in this reflected the identity of each tribe. country, particularly for Māori. From The subject of Arnold Wilson’s Carved pou, panels on the wharenui the first arrival of Europeans the installation is clearly spelled out – and on waka were the primary face of the country has altered his concern is with the timber images of Māori sculptors, and his greatly and many Māori felt cut off industry. He writes, “Where have all pou updates this tradition. He from their traditional land and the trees gone, overseas every one” contrasts this with a pile of bark resources. As the country became on a box on top of a pile of bark chips, which is a reference to the industrialised this process has chips. -

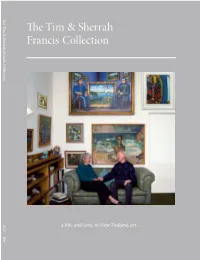

The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection

The Tim & Sherrah FrancisTimSherrah & Collection The The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection A+O 106 a life, and love, in New Zealand art… The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection Art + Object 7–8 September 2016 Tim and Sherrah Francis, Washington D.C., 1990. Contents 4 Our Friends, Tim and Sherrah Jim Barr & Mary Barr 10 The Tim and Sherrah Francis Collection: A Love Story… Ben Plumbly 14 Public Programme 15 Auction Venue, Viewing and Sale details Evening One 34 Yvonne Todd: Ben Plumbly 38 Michael Illingworth: Ben Plumbly 44 Shane Cotton: Kriselle Baker 47 Tim Francis on Shane Cotton 53 Gordon Walters: Michael Dunn 64 Tim Francis on Rita Angus 67 Rita Angus: Vicki Robson 72 Colin McCahon: Michael Dunn 75 Colin McCahon: Laurence Simmons 79 Tim Francis on The Canoe Tainui 80 Colin McCahon, The Canoe Tainui: Peter Simpson 98 Bill Hammond: Peter James Smith 105 Toss Woollaston: Peter Simpson 108 Richard Killeen: Laurence Simmons 113 Milan Mrkusich: Laurence Simmons 121 Sherrah Francis on The Naïve Collection 124 Charles Tole: Gregory O’Brien 135 Tim Francis on Toss Woollaston Evening Two 140 Art 162 Sherrah Francis on The Ceramics Collection 163 New Zealand Pottery 168 International Ceramics 170 Asian Ceramics 174 Books 188 Conditions of Sale 189 Absentee Bid Form 190 Artist Index All quotes, essays and photographs are from the Francis family archive. This includes interviews and notes generously prepared by Jim Barr and Mary Barr. Our Friends, Jim Barr and Mary Barr Tim and Sherrah Tim and Sherrah in their Wellington home with Kate Newby’s Loads of Difficult. -

Download PDF Catalogue

THE 21st CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE A+O 7 A+O THE 21st CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE 3 Abbey Street, Newton PO Box 68 345, Newton Auckland 1145, New Zealand Phone +64 9 354 4646 Freephone 0800 80 60 01 Facsimile +64 9 354 4645 [email protected] www.artandobject.co.nz Auction from 1pm Saturday 15 September 3 Abbey Street, Newton, Auckland. Note: Intending bidders are asked to turn to page 14 for viewing times and auction timing. Cover: lot 256, Dennis Knight Turner, Exhibition Thoughts on the Bev & Murray Gow Collection from John Gow and Ben Plumbly I remember vividly when I was twelve years old, hopping in the car with Dad, heading down the dusty rural Te Miro Road to Cambridge to meet the train from Auckland. There was a special package on this train, a painting that my parents had bought and I recall the ceremony of unwrapping and Mum and Dad’s obvious delight, but being completely perplexed by this ‘artwork’. Now I look at the Woollaston watercolour and think how farsighted they were. Dad’s love of art was fostered at Auckland University through meeting Diane McKegg (nee Henderson), the daughter of Louise Henderson. As a student he subsequently bought his first painting from Louise, an oil on paper, Rooftops Newmarket. After marrying Beverley South, their mutual interest in the arts ensured the collection’s growth. They visited exhibitions in the Waikato and Auckland and because Mother was a soprano soloist, and a member of the Hamilton Civic Bev and Murray Gow Choir, concert trips to Auckland, Tauranga, New Plymouth, Gisborne and other centres were in their Orakei home involved. -

Olivia Spencer Bower Retrospective 1977

759. 993 SPE FOOTNOTES (1) BlIlh CerllllCale venlled (2) The IWO sefles at Holton Ie MOOf Hall p<ilf'llangs 0lMa made on both 0CC3Sl00S 01 her return tnps 10 England are not SImply palntll'lgs at an 3rbllrary place they ale a pilgrimage of lamily identity - a lost hefllage. The cows,trees. horses, fields. poocls. msundial have an unpl'eceoellled exactness of placing Their presence IS as ~ In larnity tradilion - immovable 35 lamity gen ealogey yel1ranSIent and rnyslerlOUSas the homes must ha ....e been 10 her. intangible. Sometimes the sundial Olivia dePIcts in the Hall paintings 'opens' right out into the surrounding spaces. other limes is embraced by Banking yellows. as otller secluded and conceale<l. Halton Ie MOOr Hall made a Slgnihcant rnpression on 0lMa. The laler 1960's serIes nave a senSlllVlty unSIJ(' passed In most of O~vta's palll\JogS It seems as If the return to the place ot the hefltage thai rnlQhl have been hers fostered in her. some of her greater artistIC slreng1hs The IocKI colour and wide IOnaI Qua~ty 01 the watercoloufs suggest a deep sense of 1oca\JOfl related to symbolic content landscape here IS the diarist 01 IeeIing ow.a has preferred not 10 sell mosl 01 these pauliings (3) Amongst Olivia's coIIeclJoo of her mother's Slade Art SChool memotabilia are some analomicaJ tile draWIngs Rosa salvaged Irom a llIe drawing etass dust bm II was dOne by one ol the 'beller' students and in keeping with the criteria at the lime. works not el«:ellent in every way were deslfoyect. -

From the Collection Disadvantaged Students Hope to Inspire Others

From the collection Arts Auckland in 1991. Featuring a predominantly earthy palette, the work is characteristic of Henderson’s cubist works where she transcribes her subject through a series of angular planes. The time-honoured subject of the reclining female nude is revitalised and reinvented under Henderson’s pencil and brush as she fractures and distorts her subject by amalgamating a series of seemingly disparate viewpoints. In line with the cubist ethos, Henderson unabashedly draws attention to the two- dimensional physicality of the work by doing away with the traditionally celebrated technique of perspective in order to create a three-dimensional illusion and the use of fine mimetic brushwork to consolidate the illusory view. Instead, the viewer is Dame Louise Henderson was born in Paris in sketching trips. Louise’s work of this period was presented with thin rubbings, and smudges of 1902 and immigrated in 1925 with her husband exhibited alongside fellow leading Christchurch crayon graze the surface of the paper in places, to New Zealand, where she studied painting at artists including Leo Bensemann, Rata Lovell-Smith drawing attention to its presence and its texture the Canterbury School of Art. and Olivia Spencer Bower. Although Louise is now while any notion of receding space is negated by Louise later moved to Auckland where she recognised as being one of the pioneering figures the background planes being pushed up directly attended classes under Archibald Fisher at the of early cubism in New Zealand, her hard-edged behind the nude form. Elam School of Fine Arts. During this time she also abstractions were often met with disdain and The work of Louise Henderson features in all worked in the Auckland studio of painter John derision by the public throughout the 1930s major public collections throughout New Zealand Weeks and subsequently in Paris under the and 1940s. -

Important Paintings & Contemporary

IMPORTANT PAINTINGS & CONTEMPORARY ART 12 APRIL The Wisdom of Crowds is the title of the American writer’s James Surowiecki’s 2004 Front cover: analysis of group psychology. His central tenets relating to collective intelligence 'Colin McCahon: On came to mind when looking back on the recent weekend of March 17/18 in Going Out with the Tide', installation view, City Gallery Wellington where ART+OBJECT held its first ever auction in the capital, offering The Wellington, 2017. Photo: Collection of Frank and Lyn Corner. Speaking of crowds the A+O team was almost Shaun Waugh. Courtesy of overwhelmed by the number of Wellington art lovers (and others from around the Colin McCahon Research country who flew in for the viewing) who visited the Corner family home for the and Publication Trust. three days of the viewing. For a complete report on this landmark collection and Page 1: auction, turn to page 4 in the introduction to the current catalogue. lot 71, Charlie Tjapangati More crowds were in evidence for the opening of Te Papa Tongarewa’s 20th Tingari Painting anniversary exhibition Toi Art. For those of us who can remember the 1998 opening exhibition Dream Collectors this new show curated by Te Papa Head of Art Charlotte Davy and her team was a radical re-proposal of the contemporary art discourse of New Zealand in 2018 – proof positive of the power of art to engage the public to the tune of over 15 000 visitors on the opening weekend. If one makes a basic back of an envelope head count that adds up to over 20 000 people who enjoyed New Zealand art over a three day period in the capital.