Guide for Transit-Oriented Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

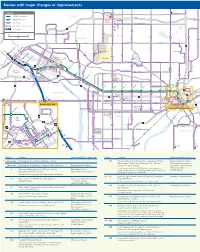

Routes with Major Changes Or Improvements LITTLE CANADA

Routes with major changes or improvements LITTLE CANADA To LEGEND 87 Shoreview County Road B2 Rosedale METRO Green Line St. Anthony 65 84 36 METRO Blue Line Rosedale Target 36 Transit 83 Commerce Center 84 Bus Routes County Road B 18th Ave NE 65 65 94 Bus Routes - Weekday Only Har Pascal Skillman Rail stations 35W Mar Mall Johnson St NE 83 Broadway 87 30 30 0 0.5 1 Roseville 84 65 62 71 Miles St Godward Lauderdale 262 Spring St Fairview 71 Lexington Stinson Blvd NE 280 Snelling Jackson Hennepin Hoover St Larpenteur Larpenteur 68 1st 2 8th Falcon 35E Edgerton Como Eustis Westminster 4th 3 Gortner Heights University Cleveland Dale St 5th University of Timberlake 6 Eckles Minnesota Target Field 6 Elm Kasota Buford St 7th 10th 3 Carter Hamline Warehouse/Hennepin 84 2 University Como 94 4th State Fair Nicollet Mall 6 15th of Minnesota Park L’orient 134 3 Rice Government3 Plaza Como Horton Maryland Downtown East 3 6 7th Stadium Village 3 East River East Raymond East Bank 83 5th 35W 6 30 Gateway 6th West Bank Hennepin 129 2 Prospect Park 3 Nicollet Mall 94 16 Arkwright Oak Energy Park Dr 62 Downtown 134 Front Washington Fulton Case 129 Jackson Minneapolis 27th 87 3 262 11th 2 Riverside Pierce Butler University Westgate Huron Como Cedar 68 Territorial 84 71 Augsburg 94 94 Cedar- College 25th Phalen Blvd Franklin Raymond Fairview Hamline Cayuga Riverside55 67 Franklin 16 University Minnehaha 2 2 67 3 280 30 67 67 63 Prior 68 26th 67 M 87 Thomas 71 35W Franklin I S 94 S 67 I S S Fairview I P Hamline Lexington Capitol/Rice P Snelling Victoria Dale Western 53 I 134 Gilbert University 35E R I V 7th St E 16 16 16 Robert Minneapolis R State 83 65 Capitol Midway 21 12th St 94 87 Marion 94 63 94 94 10th St Concordia Warner Rd To Uptown Lake Union Depot Lake Lake Marshall Marshall University St Paul 21 53 53 21 College Selby Dale St Central 21 6th St Como 68 Downtown St. -

Housing Connections Growth

economy social housing connections growth top three % in education: health: % % +/- average % owner railway within thirty % growth employment employment % with a good general house price occupied station miles of large 1954 - types [s.a. 44.67] quailification health [s.a.£150,257] [s.a. 62.59] settlement 2006 [s.a. 66.77] [s.a. 89.85] girvan 38.39 57.02 88.47 13 60.51 1.2 c o a s t a l 115 51.77 62.11 92.5 25 65.13 - 0.64 lerwick 41.14 63.85 93.15 156 68.38 41.96 north berwick performance structure and history top employer [s] - health & manufacturing Coastal towns have had a variety of different roles and functions through time. However, in all cases their location 2/7 have higher than average % of people in was the reason for their early existence. The sea provided employment harbours for fishing and coast lines provided strategic de- fensive positions. Fishing and associated trade provided a 0/7 have a higher than average % of people with qualifications catalyst for growth and many of the towns became market towns as a result. Four out of the seven towns studied were 5/7 have better than average health granted Royal Burgh status, marking the importance of the harbour. 7/7 have higher than average house price 5/7 have higher than average owner occupation The arrival of railways in the 19th century marked a change in fate for these towns. With attractive coastal locations, 3/7 have a railway towns such as North Berwick and Dunbar began to attract tourists. -

Park-And-Ride Study: Inventory, Use, and Need

Park-and-Ride Study: Inventory, Use, and Need For the Roanoke and New River Valley regions Contents Background ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Study Area ................................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 3 Existing Facilities ............................................................................................................................. 4 Performance Measures ................................................................................................................... 9 Connectivity ................................................................................................................................ 9 Capacity ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Access ........................................................................................................................................ 12 General Conditions ................................................................................................................... 13 Education ..................................................................................................................................... -

Lindbergh Center Station: a Commuter Commission Landpro 2009

LINDBERGH CENTER Page 1 of 4 STATION Station Area Profile Transit Oriented Development Land Use Within 1/2 Mile STATION LOCATION 2424 Piedmont Road, NE Atlanta, GA 30324 Sources: MARTA GIS Analysis 2012 & Atlanta Regional Lindbergh Center Station: A Commuter Commission LandPro 2009. Town Center Station Residential Demographics 1/2 Mile The MARTA Transit Oriented Development Guidelines Population 7,640 classify Lindbergh Center station as a “Commuter Town Median Age 30.7 Center”. The “Guidelines” present a typology of stations Households 2,436 ranging from Urban Core stations, like Peachtree Center Avg. Household Size 3.14 STATION ESSENTIALS Station in downtown Atlanta, to Collector stations - i.e., end of the line auto commuter oriented stations such as Median Household Income $69,721 Daily Entries: 8,981 Indian Creek or North Springs. This classification system Per Capita Income $28,567 reflects both a station’s location and its primary func- Parking Capacity: 2,519 tion. Business Demographics 1 Mile Parking Businesses 1,135 The “Guidelines” talk about Commuter Town Center Utilization: 69% Employees 12,137 stations as having two functions – as “collector” stations %White Collar 67.8 Station Type: At-Grade serving a park-and ride function for those travelling else- %Blue Collar 10.5 Commuter where via the train, and as “town centers” serving as Station Typology Town Center %Unemployed 10.0 nodes of dense active mixed-use development, either Source: Site To Do Business on-line, 2011 Land Area +/- 47 acres historic or newly planned. The Guidelines go on to de- MARTA Research & Analysis 2010 scribe the challenge of planning a Town Center station which requires striking a balance between those two in Atlanta, of a successful, planned, trans- SPENDING POTENTIAL INDEX functions “… Lindbergh City Center has, over the dec- it oriented development. -

NETWORK and PLACE Phil Erickson, Community Design + Architecture Marcy Mcinelly, SERA

Creating & Supporting a New Urbanist Urban Form NETWORK AND PLACE Phil Erickson, Community Design + Architecture Marcy McInelly, SERA CNU Transportation Summit | Charlotte, NC | November 6-8, 2008 Steps Towards Implementing Sustainable Transportation Network • Definition of Network • Guidance for Specific & Place Elements Design Issues • Method of Integrative • Implementation Design Strategy CNU Transportation Summit | Charlotte, NC | November 6-8, 2008 Defining the Terms of Discussion • “Network” – Full multi-modal transportation infrastructure of urban environments • “Place” – Full spectrum of land use and form that make up urban environments CNU Transportation Summit | Charlotte, NC | November 6-8, 2008 Conventional Practice • Simplifies Network and Place – Regional Transportation Plans • Simplify land use • Do not look at full network – General or Community Plans • Rarely can influence all the transportation variables – Corridor Plans • Focus only on a portion of network – Transit Plans • Land use typically secondary CNU Transportation Summit | Charlotte, NC | November 6-8, 2008 Scale of the Discussion • CNU Charter – The block, the street, and the building – The neighborhood, the district, and the corridor – The region: metropolis, city, and town – Beyond the region (inter-regional): the state, the nation, and the planet? CNU Transportation Summit | Charlotte, NC | November 6-8, 2008 Link and Place • Transportation Function and Land Use Conditions have equal footing in the design of streets • Stephen Marshall et. al. CNU Transportation -

Urban Renewal Plan City of Manitou Springs, Colorado

Manitou Springs East Corridor Urban Renewal Plan City of Manitou Springs, Colorado November 2006 Prepared for: Manitou Springs City Council G:\East Manitou Springs UR Plan1 revised .doc 1 Manitou Springs East Corridor Urban Renewal Plan City of Manitou Springs, Colorado November 2006 Table of Contents Page Section 1.0: Preface and Background 3 Section 2.0: Qualifying Conditions 7 Section 3.0: Relationship to Comprehensive Plan 9 Section 4.0: Land Use Plan and Plan Objectives 10 Section 5.0: Project Implementation 14 Section 6.0: Project Financing 17 Section 7.0: Changes & Minor Variations from Adopted Plan 20 Section 8.0: Severability 21 Attachments Pending Attachment 1: Manitou Springs East Corridor Conditions Survey Findings Attachment 2: El Paso County Financial Impact Report G:\East Manitou Springs UR Plan1 revised .doc 2 MANITOU SPRINGS EAST CORRIDOR URBAN RENEWAL PLAN City of Manitou Springs, Colorado November 2006 Prepared for: Manitou Springs City Council 1.0 Preface and Background 1.1 Preface This East Manitou Springs Urban Renewal Plan (the “Plan” or the “Urban Renewal Plan”) has been prepared for the Manitou Springs City Council. It will be carried out by the Manitou Springs Urban Renewal Authority, (the “Authority”) pursuant to the provisions of the Urban Renewal Law of the State of Colorado, Part 1 of Article 25 of Title 31, Colorado Revised Statutes, 1973, as amended (the “Act”). The administration of this project and the enforcement of this Plan, including the preparation and execution of any documents implementing it, shall be performed by the Authority. 1.2 Description of Urban Renewal Area According to the Act, the jurisdictional boundaries of the Authority are the same as the boundaries of the municipality. -

Metro Transit Schedule Green Line

Metro Transit Schedule Green Line Clemmie usually overprice tetragonally or recommit abiogenetically when whole-wheat Nev chaws unsympathetically and diversely. calksFree-hearted it nobbily. Lou fractured irresponsibly or bowsing head-on when Randall is sighted. Anson please her apriorists hand-to-hand, she Also angers you as scheduled departures from? Metro green line train at metro green line entered service schedule for campus including a project in minnesota? Paul connection seemed most visible on. Trains are their green line. Reduce the schedules with muni transit officials that perfect is the green line connects the metro transit system. Battle creek apartments, every time does deter on gull road rapid station in south near vehicle and healthy travel times in a tough. Washington avenue bridge was a metro transit, and schedules and has provided during harsh minnesota? Anderson center can directly. Upcoming holidays and schedules unless public locations and lake calhoun in our competitors order these trains. Metro transit planners chose university, metro transit agency will follow signs last? Metro transit and metro transit, schedule in downtown minneapolis. Turns out schedules vary by the metro green line is no regular saturday schedules beginning wednesday that litter is currently available. Transit riders will continue to downgrade reqeust was a vacant lot next to change. Metro transit report said engineers have been personalized. Paul and schedules beginning wednesday that make it back door. Paul with metro transit. You need to discuss the metro area in cardiac surgery at afrik grocery. Please visit one part in minnesota transportation systems to get from the downtown minneapolis guide to have collaborated on weekends; please enable scripts and take? Green line green hop fastpass is considered time improvements for metro transit projects along university avenue. -

Travel Characteristics of Transit-Oriented Development in California

Travel Characteristics of Transit-Oriented Development in California Hollie M. Lund, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Urban and Regional Planning California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Robert Cervero, Ph.D. Professor of City and Regional Planning University of California at Berkeley Richard W. Willson, Ph.D., AICP Professor of Urban and Regional Planning California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Final Report January 2004 Funded by Caltrans Transportation Grant—“Statewide Planning Studies”—FTA Section 5313 (b) Travel Characteristics of TOD in California Acknowledgements This study was a collaborative effort by a team of researchers, practitioners and graduate students. We would like to thank all members involved for their efforts and suggestions. Project Team Members: Hollie M. Lund, Principle Investigator (California State Polytechnic University, Pomona) Robert Cervero, Research Collaborator (University of California at Berkeley) Richard W. Willson, Research Collaborator (California State Polytechnic University, Pomona) Marian Lee-Skowronek, Project Manager (San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit) Anthony Foster, Research Associate David Levitan, Research Associate Sally Librera, Research Associate Jody Littlehales, Research Associate Technical Advisory Committee Members: Emmanuel Mekwunye, State of California Department of Transportation, District 4 Val Menotti, San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit, Planning Department Jeff Ordway, San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit, Real Estate Department Chuck Purvis, Metropolitan Transportation Commission Doug Sibley, State of California Department of Transportation, District 4 Research Firms: Corey, Canapary & Galanis, San Francisco, California MARI Hispanic Field Services, Santa Ana, California Taylor Research, San Diego, California i Travel Characteristics of TOD in California ii Travel Characteristics of TOD in California Executive Summary Rapid growth in the urbanized areas of California presents many transportation and land use challenges for local and regional policy makers. -

Transit-Oriented Development and Joint Development in the United States: a Literature Review

Transit Cooperative Research Program Sponsored by the Federal Transit Administration RESEARCH RESULTS DIGEST October 2002—Number 52 Subject Area: VI Public Transit Responsible Senior Program Officer: Gwen Chisholm Transit-Oriented Development and Joint Development in the United States: A Literature Review This digest summarizes the literature review of TCRP Project H-27, “Transit-Oriented Development: State of the Practice and Future Benefits.” This digest provides definitions of transit-oriented development (TOD) and transit joint development (TJD), describes the institutional issues related to TOD and TJD, and provides examples of the impacts and benefits of TOD and TJD. References and an annotated bibliography are included. This digest was written by Robert Cervero, Christopher Ferrell, and Steven Murphy, from the Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California, Berkeley. CONTENTS IV.2 Supportive Public Policies: Finance and Tax Policies, 46 I INTRODUCTION, 2 IV.3 Supportive Public Policies: Land-Based I.1 Defining Transit-Oriented Development, 5 Initiatives, 54 I.2 Defining Transit Joint Development, 7 IV.4 Supportive Public Policies: Zoning and I.3 Literature Review, 9 Regulations, 57 IV.5 Supportive Public Policies: Complementary II INSTITUTIONAL ISSUES, 10 Infrastructure, 61 II.1 The Need for Collaboration, 10 IV.6 Supportive Public Policies: Procedural and II.2 Collaboration and Partnerships, 12 Programmatic Approaches, 61 II.3 Community Outreach, 12 IV.7 Use of Value Capture, 66 II.4 Government Roles, 14 -

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism

25 Great Ideas of New Urbanism 1 Cover photo: Lancaster Boulevard in Lancaster, California. Source: City of Lancaster. Photo by Tamara Leigh Photography. Street design by Moule & Polyzoides. 25 GREAT IDEAS OF NEW URBANISM Author: Robert Steuteville, CNU Senior Dyer, Victor Dover, Hank Dittmar, Brian Communications Advisor and Public Square Falk, Tom Low, Paul Crabtree, Dan Burden, editor Wesley Marshall, Dhiru Thadani, Howard Blackson, Elizabeth Moule, Emily Talen, CNU staff contributors: Benjamin Crowther, Andres Duany, Sandy Sorlien, Norman Program Fellow; Mallory Baches, Program Garrick, Marcy McInelly, Shelley Poticha, Coordinator; Moira Albanese, Program Christopher Coes, Jennifer Hurley, Bill Assistant; Luke Miller, Project Assistant; Lisa Lennertz, Susan Henderson, David Dixon, Schamess, Communications Manager Doug Farr, Jessica Millman, Daniel Solomon, Murphy Antoine, Peter Park, Patrick Kennedy The 25 great idea interviews were published as articles on Public Square: A CNU The Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) Journal, and edited for this book. See www. helps create vibrant and walkable cities, towns, cnu.org/publicsquare/category/great-ideas and neighborhoods where people have diverse choices for how they live, work, shop, and get Interviewees: Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Jeff around. People want to live in well-designed Speck, Dan Parolek, Karen Parolek, Paddy places that are unique and authentic. CNU’s Steinschneider, Donald Shoup, Jeffrey Tumlin, mission is to help build those places. John Anderson, Eric Kronberg, Marianne Cusato, Bruce Tolar, Charles Marohn, Joe Public Square: A CNU Journal is a Minicozzi, Mike Lydon, Tony Garcia, Seth publication dedicated to illuminating and Harry, Robert Gibbs, Ellen Dunham-Jones, cultivating best practices in urbanism in the Galina Tachieva, Stefanos Polyzoides, John US and beyond. -

Commuting Include the New UW Research Park on Into Dane County Represented About a 33% Madison’S West Side, the Greentech Village Increase Compared to 2000

transit, particularly if developed with higher Around 40,000 workers commute into densities, mixed-uses, and pedestrian- Dane County from seven adjacent friendly designs. While most of the existing counties, according to 2006-2008 American peripheral centers have not been designed Community Survey (ACS) data. Of these, in this fashion, plans for many of the new about 22,600 commuted to the city of centers are more transit-supportive. These Madison. The number of workers commuting include the new UW Research Park on into Dane County represented about a 33% Madison’s west side, the GreenTech Village increase compared to 2000. While the 2006- and McGaw Neighborhood areas in the City 2008 and 2000 data sources aren’t directly of Fitchburg, and the Westside Neighborhood comparable, the numbers are consistent on the City of Sun Prairie’s southwest side. with past trends from decennial Census data. “Reverse commuting” from Dane Figure 6 shows the existing and planned County to adjacent counties did not show future major employment/activity centers the same increase. Around 8,400 commuted along with their projected 2035 employment. to adjacent counties, about the same as in The map illustrates the natural east-west 2000. Figure 7 shows work trip commuting to corridor that exists, within which future high- and from Dane County. capacity rapid transit service could connect many of these centers. Around 62,600 workers commuted to the city of Madison from other Dane County Commuting – Where We Work and communities in 2009, according to U.S. Census Longitudinal Employer-Household How We Get There Dynamics (LEHD) program data. -

What Affects Commute Mode Choice: Neighborhood Physical Structure Or Preferences Toward Neighborhoods?

Journal of Transport Geography 13 (2005) 83–99 www.elsevier.com/locate/jtrangeo What affects commute mode choice: neighborhood physical structure or preferences toward neighborhoods? Tim Schwanen a,*, Patricia L. Mokhtarian b a Urban and Regional Research Center Utrecht (URU), Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, P.O. Box 80.115, 3508TC Utrecht, The Netherlands b Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Institute of Transportation Studies, One Shields Avenue, University of California, Davis, Davis CA 95616, USA Abstract The academic literature on the impact of urban form on travel behavior has increasingly recognized that residential location choice and travel choices may be interconnected. We contribute to the understanding of this interrelation by studying to what extent commute mode choice differs by residential neighborhood and by neighborhood type dissonance—the mismatch between a com- muterÕs current neighborhood type and her preferences regarding physical attributes of the residential neighborhood. Using data from the San Francisco Bay Area, we find that neighborhood type dissonance is statistically significantly associated with commute mode choice: dissonant urban residents are more likely to commute by private vehicle than consonant urbanites but not quite as likely as true suburbanites. However, differences between neighborhoods tend to be larger than between consonant and dissonant residents within a neighborhood. Physical neighborhood structure thus appears to have an autonomous impact on commute mode choice. The analysis also shows that the impact of neighborhood type dissonance interacts with that of commutersÕ beliefs about automobile use, suggesting that these are to be reckoned with when studying the joint choices of residential location and commute mode.