Phylogenetic Relationships Among West Indian Xenodontine Snakes (Serpentes; Colubridae) with Comments on the Phylogeny of Some Mainland Xenodontines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uromacer Catesbyi (Schlegel) 1. Uromacer Catesbyi Catesbyi Schlegel 2. Uromacer Catesbyi Cereolineatus Schwartz 3. Uromacer Cate

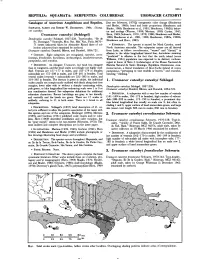

T 356.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE UROMACER CATESBYI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. [but see Schwartz,' 1970]); ontogenetic color change (Henderson and Binder, 1980); head and body proportions (Henderson and SCHWARTZ,ALBERTANDROBERTW. HENDERSON.1984. Uroma• Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981; Henderson, 1982b); behav• cer catesbyi. ior and ecology (Werner, 1909; Mertens, 1939; Curtiss, 1947; Uromacer catesbyi (Schlegel) Horn, 1969; Schwartz, 1970, 1979, 1980; Henderson and Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981, 1982; Henderson, 1982a, 1982b; Dendrophis catesbyi Schlegel, 1837:226. Type-locality, "lie de Henderson and Horn, 1983). St.- Domingue." Syntypes, Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat., Paris, 8670• 71 (sexes unknown) taken by Alexandre Ricord (date of col• • ETYMOLOGY.The species is named for Mark Catesby, noted lection unknown) (not examined by authors). North American naturalist. The subspecies names are all derived Uromacer catesbyi: Dumeril, Bibron, and Dumeril, 1854:72l. from Latin, as follow: cereolineatus, "waxen" and "thread," in allusion to the white longitudinal lateral line; hariolatus meaning • CONTENT.Eight subspecies are recognized, catesbyi, cereo• "predicted" in allusion to the fact that the north island (sensu lineatus,frondicolor, hariolatus, inchausteguii, insulaevaccarum, Williams, 1961) population was expected to be distinct; inchaus• pampineus, and scandax. teguii in honor of Sixto J. Inchaustegui, of the Museo Nacional de • DEFINITION.An elongate Uromacer, but head less elongate Historia Natural de Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana; insu• than in congeners, and the head scales accordingly not highly mod• laevaccarum, a literal translation of lIe-a-Vache (island of cows), ified. Ventrals are 157-177 in males, and 155-179 in females; pampineus, "pertaining to vine tendrils or leaves;" and scandax, subcaudals are 172-208 in males, and 159-201 in females. -

Other Contributions

Other Contributions NATURE NOTES Amphibia: Caudata Ambystoma ordinarium. Predation by a Black-necked Gartersnake (Thamnophis cyrtopsis). The Michoacán Stream Salamander (Ambystoma ordinarium) is a facultatively paedomorphic ambystomatid species. Paedomorphic adults and larvae are found in montane streams, while metamorphic adults are terrestrial, remaining near natal streams (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). Streams inhabited by this species are immersed in pine, pine-oak, and fir for- ests in the central part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Luna-Vega et al., 2007). All known localities where A. ordinarium has been recorded are situated between the vicinity of Lake Patzcuaro in the north-central portion of the state of Michoacan and Tianguistenco in the western part of the state of México (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). This species is considered Endangered by the IUCN (IUCN, 2015), is protected by the government of Mexico, under the category Pr (special protection) (AmphibiaWeb; accessed 1April 2016), and Wilson et al. (2013) scored it at the upper end of the medium vulnerability level. Data available on the life history and biology of A. ordinarium is restricted to the species description (Taylor, 1940), distribution (Shaffer, 1984; Anderson and Worthington, 1971), diet composition (Alvarado-Díaz et al., 2002), phylogeny (Weisrock et al., 2006) and the effect of habitat quality on diet diversity (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). We did not find predation records on this species in the literature, and in this note we present information on a predation attack on an adult neotenic A. ordinarium by a Thamnophis cyrtopsis. On 13 July 2010 at 1300 h, while conducting an ecological study of A. -

Herpetological Information Service No

Type Descriptions and Type Publications OF HoBART M. Smith, 1933 through June 1999 Ernest A. Liner Houma, Louisiana smithsonian herpetological information service no. 127 2000 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. Introduction Hobart M. Smith is one of herpetology's most prolific autiiors. As of 30 June 1999, he authored or co-authored 1367 publications covering a range of scholarly and popular papers dealing with such diverse subjects as taxonomy, life history, geographical distribution, checklists, nomenclatural problems, bibliographies, herpetological coins, anatomy, comparative anatomy textbooks, pet books, book reviews, abstracts, encyclopedia entries, prefaces and forwords as well as updating volumes being repnnted. The checklists of the herpetofauna of Mexico authored with Dr. Edward H. Taylor are legendary as is the Synopsis of the Herpetofalhva of Mexico coauthored with his late wife, Rozella B. -

CAT Vertebradosgt CDC CECON USAC 2019

Catálogo de Autoridades Taxonómicas de vertebrados de Guatemala CDC-CECON-USAC 2019 Centro de Datos para la Conservación (CDC) Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala Este documento fue elaborado por el Centro de Datos para la Conservación (CDC) del Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Guatemala, 2019 Textos y edición: Manolo J. García. Zoólogo CDC Primera edición, 2019 Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (Cecon) de la Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala ISBN: 978-9929-570-19-1 Cita sugerida: Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas [Cecon]. (2019). Catálogo de autoridades taxonómicas de vertebrados de Guatemala (Documento técnico). Guatemala: Centro de Datos para la Conservación [CDC], Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas [Cecon], Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala [Usac]. Índice 1. Presentación ............................................................................................ 4 2. Directrices generales para uso del CAT .............................................. 5 2.1 El grupo objetivo ..................................................................... 5 2.2 Categorías taxonómicas ......................................................... 5 2.3 Nombre de autoridades .......................................................... 5 2.4 Estatus taxonómico -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

De Los Reptiles Del Yasuní

guía dinámica de los reptiles del yasuní omar torres coordinador editorial Lista de especies Número de especies: 113 Amphisbaenia Amphisbaenidae Amphisbaena bassleri, Culebras ciegas Squamata: Serpentes Boidae Boa constrictor, Boas matacaballo Corallus hortulanus, Boas de los jardines Epicrates cenchria, Boas arcoiris Eunectes murinus, Anacondas Colubridae: Dipsadinae Atractus major, Culebras tierreras cafés Atractus collaris, Culebras tierreras de collares Atractus elaps, Falsas corales tierreras Atractus occipitoalbus, Culebras tierreras grises Atractus snethlageae, Culebras tierreras Clelia clelia, Chontas Dipsas catesbyi, Culebras caracoleras de Catesby Dipsas indica, Culebras caracoleras neotropicales Drepanoides anomalus, Culebras hoz Erythrolamprus reginae, Culebras terrestres reales Erythrolamprus typhlus, Culebras terrestres ciegas Erythrolamprus guentheri, Falsas corales de nuca rosa Helicops angulatus, Culebras de agua anguladas Helicops pastazae, Culebras de agua de Pastaza Helicops leopardinus, Culebras de agua leopardo Helicops petersi, Culebras de agua de Peters Hydrops triangularis, Culebras de agua triángulo Hydrops martii, Culebras de agua amazónicas Imantodes lentiferus, Cordoncillos del Amazonas Imantodes cenchoa, Cordoncillos comunes Leptodeira annulata, Serpientes ojos de gato anilladas Oxyrhopus petolarius, Falsas corales amazónicas Oxyrhopus melanogenys, Falsas corales oscuras Oxyrhopus vanidicus, Falsas corales Philodryas argentea, Serpientes liana verdes de banda plateada Philodryas viridissima, Serpientes corredoras -

Zootaxa, Molecular Phylogeny, Classification, and Biogeography Of

Zootaxa 2067: 1–28 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Molecular phylogeny, classification, and biogeography of West Indian racer snakes of the Tribe Alsophiini (Squamata, Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae) S. BLAIR HEDGES1, ARNAUD COULOUX2, & NICOLAS VIDAL3,4 1Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Lab, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Genoscope. Centre National de Séquençage, 2 rue Gaston Crémieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry Cedex, France www.genoscope.fr 3UMR 7138, Département Systématique et Evolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France 4Corresponding author. E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Most West Indian snakes of the family Dipsadidae belong to the Subfamily Xenodontinae and Tribe Alsophiini. As recognized here, alsophiine snakes are exclusively West Indian and comprise 43 species distributed throughout the region. These snakes are slender and typically fast-moving (active foraging), diurnal species often called racers. For the last four decades, their classification into six genera was based on a study utilizing hemipenial and external morphology and which concluded that their biogeographic history involved multiple colonizations from the mainland. Although subsequent studies have mostly disagreed with that phylogeny and taxonomy, no major changes in the classification have been proposed until now. Here we present a DNA sequence analysis of five mitochondrial genes and one nuclear gene in 35 species and subspecies of alsophiines. Our results are more consistent with geography than previous classifications based on morphology, and support a reclassification of the species of alsophiines into seven named and three new genera: Alsophis Fitzinger (Lesser Antilles), Arrhyton Günther (Cuba), Borikenophis Hedges & Vidal gen. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

Crisantophis Villa Crisantophis Nevermanni (Dunn)

429.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: COLUBRIDAE CRISANTOPHIS, C. NEVERMANNI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. 200 400 Mi 1 J Villa, Jaime D. 1988. Crisantophis, C. nevennanni. 1 ,, 300 Km. .r'·• Crisantophis villa I ! ') Crisantophis Villa 1971: 173. Type species, Conophis nevennanni \ Dunn 1937, by monotypy. • Content. A single species, Crisantophis nevennanni, is recog• nized. • Def"mition. Medium-sized snakes (maximum total length 825mm) of generalized colubrid features (superficially resembling Coniophanes and Conophis). The head is moderately distinct from the neck, its profile is rounded in outline, with the rostral slightly overhanging the lower jaw, but not recurved as in Conophis. The eye and the pupil are round; the nasal is divided; there are 13-14 maxillary teeth, increasing in size posteriorly and followed by a short diastema and by one or two enlarged fangs, laterally compressed and grooved througout their length; the palatine bears 10-11 teeth that increase in size posteriorly, as do those of the pterygoid (33-35) and Map. Solidcircle indicates the type-locality. Open circles mark other dentary (21-22); the hemipenes are long (reaching to subcaudals 12• localities. 15), slender, subcylindrical and bilobed, with the branches of the sulcus spermaticus being of the "centripetal" type (of Myers and Aserri [SanJose Province, Canton de Aserri, Costa Rica] (a few Campbell, 1981), diverging moderately at the base of the fork and miles south of San Jose)." Holotype, Academy of Natural Sci• extending onto the lobes ofthe hemipenis in a centrolineal direction, ences of Philadelphia No. 22423, a young female obtained by but each branch curving medially and thereafter facing its fellow Manuel Valerio, date unknown (examined by author). -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

Ecological Functions of Neotropical Amphibians and Reptiles: a Review

Univ. Sci. 2015, Vol. 20 (2): 229-245 doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.SC20-2.efna Freely available on line REVIEW ARTICLE Ecological functions of neotropical amphibians and reptiles: a review Cortés-Gomez AM1, Ruiz-Agudelo CA2 , Valencia-Aguilar A3, Ladle RJ4 Abstract Amphibians and reptiles (herps) are the most abundant and diverse vertebrate taxa in tropical ecosystems. Nevertheless, little is known about their role in maintaining and regulating ecosystem functions and, by extension, their potential value for supporting ecosystem services. Here, we review research on the ecological functions of Neotropical herps, in different sources (the bibliographic databases, book chapters, etc.). A total of 167 Neotropical herpetology studies published over the last four decades (1970 to 2014) were reviewed, providing information on more than 100 species that contribute to at least five categories of ecological functions: i) nutrient cycling; ii) bioturbation; iii) pollination; iv) seed dispersal, and; v) energy flow through ecosystems. We emphasize the need to expand the knowledge about ecological functions in Neotropical ecosystems and the mechanisms behind these, through the study of functional traits and analysis of ecological processes. Many of these functions provide key ecosystem services, such as biological pest control, seed dispersal and water quality. By knowing and understanding the functions that perform the herps in ecosystems, management plans for cultural landscapes, restoration or recovery projects of landscapes that involve aquatic and terrestrial systems, development of comprehensive plans and detailed conservation of species and ecosystems may be structured in a more appropriate way. Besides information gaps identified in this review, this contribution explores these issues in terms of better understanding of key questions in the study of ecosystem services and biodiversity and, also, of how these services are generated. -

Stephen D. Busack

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH AND BIBLIOGRAPHY OF STEPHEN D. BUSACK Stephen D. Busack Rochester, New York SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 154 2018 . SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The first number of the SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE series appeared in 1968. SHIS number 1 was a list of herpetological publications arising from within or through the Smithsonian Institution and its collections entity, the United States National Museum (USNM). The latter exists now as little more than the occasional title for the registration activities of the National Museum of Natural History. No. 1 was prepared and printed by J. A. Peters, then Curator-in-Charge of the Division of Amphibians & Reptiles. The availability of a NASA translation service and assorted indices encouraged him to continue the series and distribute these items on an irregular schedule. The series continues under that tradition. Specifically, the SHIS series distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, and unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such an item, please contact George Zug [zugg @ si.edu] for its consideration for distribution through the SHIS series. Our increasingly digital world is changing the manner of our access to research literature and that is now true for SHIS publications. They are distributed now as pdf documents through two Smithsonian outlets: BIODIVERSITY HERITAGE LIBRARY. www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/15728 All numbers from 1 to 131 [1968-2001] available in BHL.