The History and Development of the Marimba Ensemble in the United States and Its Current Status in College and University Percussion Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents

THE CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA WHAT IS AN ORCHESTRA? Student Learning Lab for The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family ...................... 3 PART 2: Let’s Listen to Nagoya Marimbas ...................... 6 PART 3: Music Learning Lab ................................................ 8 2 PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family An orchestra consists of musicians organized by instrument “family” groups. The four instrument families are: strings, woodwinds, brass and percussion. Today we are going to explore the percussion family. Get your tapping fingers and toes ready! The percussion family includes all of the instruments that are “struck” in some way. We have no official records of when humans first used percussion instruments, but from ancient times, drums have been used for tribal dances and for communications of all kinds. Today, there are more instruments in the percussion family than in any other. They can be grouped into two types: 1. Percussion instruments that make just one pitch. These include: Snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, wood block, gong, maracas and castanets Triangle Castanets Tambourine Snare Drum Wood Block Gong Maracas Bass Drum Cymbals 3 2. Percussion instruments that play different pitches, even a melody. These include: Kettle drums (also called timpani), the xylophone (and marimba), orchestra bells, the celesta and the piano Piano Celesta Orchestra Bells Xylophone Kettle Drum How percussion instruments work There are several ways to get a percussion instrument to make a sound. You can strike some percussion instruments with a stick or mallet (snare drum, bass drum, kettle drum, triangle, xylophone); or with your hand (tambourine). -

The Meanings of Marimba Music in Rural Guatemala

The Meanings of Marimba Music in Rural Guatemala Sergio J. Navarrete Pellicer Ph D Thesis in Social Anthropology University College London University of London October 1999 ProQuest Number: U643819 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U643819 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis investigates the social and ideological process of the marimba musical tradition in rural Guatemalan society. A basic assumption of the thesis is that “making music” and “talking about music” are forms of communication whose meanings arise from the social and cultural context in which they occur. From this point of view the main aim of this investigation is the analysis of the roles played by music within society and the construction of its significance as part of the social and cultural process of adaptation, continuity and change of Achi society. For instance the thesis elucidates how the dynamic of continuity and change affects the transmission of a musical tradition. The influence of the radio and its popular music on the teaching methods, music genres and styles of marimba music is part of a changing Indian society nevertheless it remains an important symbols of locality and ethnic identity. -

Developing a Four-Mallet Marimba Technique Featuring the Alternation

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Developing a four-mallet marimba technique featuring the alternation of mallets in each hand for linear passages and the application of this technique to transcriptions of selected keyboard works by J.S. Bach Thomas Allen Zirkle Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zirkle, Thomas Allen, "Developing a four-mallet marimba technique featuring the alternation of mallets in each hand for linear passages and the application of this technique to transcriptions of selected keyboard works by J.S. Bach" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3099. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3099 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. DEVELOPING A FOUR-MALLET MARIMBA TECHNIQUE FEATURING THE ALTERNATION OF MALLETS IN EACH HAND FOR LINEAR PASSAGES AND THE APPLICATION OF THIS TECHNIQUE TO TRANSCRIPTIONS OF SELECTED KEYBOARD WORKS BY J.S. BACH A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The Department of Music by Thomas Allen Zirkle B.S., Ball State University, 1993 M.M., Southern Illinois University, 1995 December 2003 Dedication This paper is dedicated to Dr. -

Ludwig-Musser 2010 Concert Percussion Catalog AV8084 2010

Welcome to the world of Ludwig/Musser Concert Percussion. The instruments in this catalog represent the finest quality and sound in percussion instruments today from a company that has been making instruments and accessories in the USA for decades. Ludwig is “The Most famous Name in Drums” since 1909 and Musser is “First in Class” for mallet percussion since 1948. Ludwig & Musser aren’t just brand names, they are men’s names. William F. Ludwig Sr. & William F. Ludwig II were gifted percussionists and astute businessmen who were innovators in the world of percussion. Clair Omar Musser was also a visionary mallet percussionist, composer, designer, engineer and leader who founded the Musser Company to be the American leader in mallet instruments. Both companies originated in the Chicago area. They joined forces in the 1960’s and originated the concept of “Total Percussion.” With our experience as a manufacturer, we have a dedicated staff of craftsmen and marketing professionals that are sensitive to the needs of the percussionist. Several on our staff are active percussionists today and have that same passion for excellence in design, quality and performance as did our founders. We are proud to be an American company competing in a global economy. Musser Marimbas, Xylophones, Chimes, Bells, & Vibraphones are available in a wide range of sizes and models to completely satisfy the needs of beginners, schools, universities and professionals. With a choice of hammered copper, smooth copper or fiberglass bowls, Ludwig Timpani always deliver the full rich sound that generations of timpanists have come to expect from Ludwig. -

The PAS Educators' Companion

The PAS Educators’ Companion A Helpful Resource of the PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY EDUCATION COMMITTEE Volume VIII Fall 2020 PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY 1 EDUCATORS’ COMPANION THE PAS EDUCATORS’ COMPANION PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY EDUCATION COMMITTEE ARTICLE AUTHORS DAVE GERHART YAMAHA CORPORATION OF AMERICA ERIK FORST MESSIAH UNIVERSITY JOSHUA KNIGHT MISSOURI WESTERN STATE UNIVERSITY MATHEW BLACK CARMEL HIGH SCHOOL MATT MOORE V.R. EATON HIGH SCHOOL MICHAEL HUESTIS PROSPER HIGH SCHOOL SCOTT BROWN DICKERSON MIDDLE SCHOOL AND WALTON HIGH SCHOOL STEVE GRAVES LEXINGTON JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL JESSICA WILLIAMS ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY EMILY TANNERT PATTERSON CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS How to reach the Percussive Arts Society: VOICE 317.974.4488 FAX 317.974.4499 E-MAIL [email protected] WEB www.pas.org HOURS Monday–Friday, 9 A.M.–5 P.M. EST PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS BUILDING A STRONG FOUNDATION OF THE SNARE DRUM FULCRUM 3 by Dr. Dave Gerhart CONSISTENCY MATTERS: Developing a Shared Vernacular for Beginning 6 Percussion and Wind Students in a Heterogeneous Classroom by Dr. Erik M. Forst PERFECT PART ASSIGNMENTS - ACHIEVING THE IMPOSSIBLE 10 by Dr. Joshua J. Knight TOOLS TO KEEP STUDENTS INTRIGUED AND MOTIVATED WHILE PRACTICING 15 FUNDAMENTAL CONCEPTS by Matthew Black BEGINNER MALLET READING: DEVELOPING A CURRICULUM THAT COVERS 17 THE BASES by Matt Moore ACCESSORIES 26 by Michael Huestis ISOLATING SKILL SETS, TECHNIQUES, AND CONCEPTS WITH 30 BEGINNING PERCUSSION by Scott Brown INCORPORATING PERCUSSION FUNDAMENTALS IN FULL BAND REHEARSAL 33 by Steve Graves YOUR YOUNG PERCUSSIONISTS CRAVE ATTENTION: Advice and Tips on 39 Instructing Young Percussionists by Jessica Williams TEN TIPS FOR FABULOUS SNARE DRUM FUNDAMENTALS 46 by Emily Tannert Patterson ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 49 2 PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY EDUCATORS’ COMPANION BUILDING A STRONG FOUNDATION OF THE SNARE DRUM FULCRUM by Dr. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

Agricola Und Das Verkehrte. Zum Umgang Mit Satztechnischen Idiosynkrasien in Musik Des Späten 15

Agricola und das Verkehrte Zum Umgang mit satztechnischen Idiosynkrasien in Musik des späten 15. Jahrhunderts Markus Roth ABSTRACT: Die vorliegende, vom Kyrie I der Missa Sine Nomine ausgehende Untersuchung wid- met sich bemerkenswerten Eigenarten der Kompositionstechnik Alexander Agricolas (1446–1506), dem schon die unmittelbaren Nachfahren bescheinigten, Dinge »auf ungewohnte Weise zu wen- den« (Hulrich Brätel 1536). Tatsächlich zeigen sich bestimmte Paradoxien im Tonsatz des späten 15. Jahrhunderts bei Agricola auf besonders eigentümliche Weise. Die Studien von Fabrice Fitch (2005; 2007) vertiefend, diskutiert der Beitrag die Frage, auf welche Weise Agricola seinerzeit Regeln ›verkehrte‹ und sich über satztechnische Normen hinwegsetzte. In diesem Zusammenhang wird der Begriff der ›mi contra fa-Latenz‹ vorgeschlagen, um den grundsätzlichen Problemen der Musica ficta zu begegnen. This essay, starting with the Kyrie I of the Missa Sine Nomine, is dedicated to some remarkable compositional idiosyncracies of Alexander Agricola (1446–1506), of whom his contemporaries attested the talent of “turning things in an unexpected manner” (Hulrich Brätel 1536). Certain pa- radoxes in the formal composition of late 15th century music appear in Agricola’s work in a strange fashion. Drawing on and furthering the studies of Fabrice Fitch (2005; 2007), this paper reveals how Agricola breaks with compositional conventions. To frame this analytical discussion, I propose the term “mi contra fa-Latenz” to explain some of the fundamental problems of musica -

Michael Praetorius's Theology of Music in Syntagma Musicum I (1615): a Politically and Confessionally Motivated Defense of Instruments in the Lutheran Liturgy

MICHAEL PRAETORIUS'S THEOLOGY OF MUSIC IN SYNTAGMA MUSICUM I (1615): A POLITICALLY AND CONFESSIONALLY MOTIVATED DEFENSE OF INSTRUMENTS IN THE LUTHERAN LITURGY Zachary Alley A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2014 Committee: Arne Spohr, Advisor Mary Natvig ii ABSTRACT Arne Spohr, Advisor The use of instruments in the liturgy was a controversial issue in the early church and remained at the center of debate during the Reformation. Michael Praetorius (1571-1621), a Lutheran composer under the employment of Duke Heinrich Julius of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, made the most significant contribution to this perpetual debate in publishing Syntagma musicum I—more substantial than any Protestant theologian including Martin Luther. Praetorius's theological discussion is based on scripture, the discourse of early church fathers, and Lutheran theology in defending the liturgy, especially the use of instruments in Syntagma musicum I. In light of the political and religious instability throughout Europe it is clear that Syntagma musicum I was also a response—or even a potential solution—to political circumstances, both locally and in the Holy Roman Empire. In the context of the strengthening counter-reformed Catholic Church in the late sixteenth century, Lutheran territories sought support from Reformed church territories (i.e., Calvinists). This led some Lutheran princes to gradually grow more sympathetic to Calvinism or, in some cases, officially shift confessional systems. In Syntagma musicum I Praetorius called on Lutheran leaders—prince-bishops named in the dedication by territory— specifically several North German territories including Brandenburg and the home of his employer in Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, to maintain Luther's reforms and defend the church they were entrusted to protect, reminding them that their salvation was at stake. -

Ovation Deacon Manual

Ovation deacon manual Breadwinner Owner's Manual Thanks to "BruDeV" from the Ovation Fan Club for this great document!!! ('S) Cliquez ici pour charger la version PDF / Please. The tone of a guitar can be described as having three components: bass, mid- range and treble. The selector switch can be considered a bass control; toward. -Ovation. Solid Bodies. 1 2-String. Deacon. Owner's Manual Like our other electric guitars, the Deacon string Experiment with the Ovation Deacon. Ovation Solid Body Owner's Manual Many thanks to my friend Karl in Germany for that great doc!!! (70'S) Click here to download Ovation Breadwinner Guitar Manual. OWNER'S MANUAL. Ovation guitars are played by countless musicians around the world including: Joan Armatrading. Dj Ashba. Charlie Benante - Anthrax. OVATION. Breadwinner or a Deacon model. It is very well built and kind of cool. playing it is very easy and the manual 1. click to enlarge. the manual 2. click to. Online home for fans of Ovation Guitars around the World. know where I can get an owners manual or reprint of one for an Ovation Deacon? Have you compared yours to another Ovation? If I recall correctly, the If you haven't seen it, there's a Breadwinner/Deacon manual here. Ovation Deacon Electric Guitar in very good condition with light playwear and dings over the entire guitar but nothing major. Dark brown burst finish on the. Ovation Breadwinner Guitar Review Scott Grove real the manual. 's Ovation Breadwinner Limited Guitar Review By Scott Grove. Groovy Music . I was going though the. -

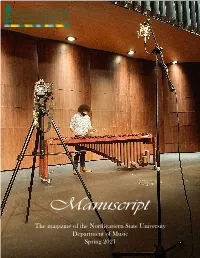

Manuscript Newsletter, Spring 2021 Edition

Manuscript The magazine of the Northeastern State University Department of Music Spring 2021 Contents 2 Welcome from the Chair Features 3 Guest Artists 5 NSU @ OkMEA 6 New Student Lounge & Opera Workshop 7 Green Country Jazz Festival 9 “Can’t stop the Music” (AKA NSU Music during a global pandemic) 11 Announcement of a new music degree 12 Student News 13 Alumni Feature 14 In Memorium 15 Faculty News 17 Endowments, Scholarships, & Donors Musicians: we are the most romantic of all artists. We believe in, and chase the illusive, intoxicating, unseen magic/beauty that exists in the universe. We are conduits for this magic/ beauty that has the ability to stir emotions that are fundamental to what it means to be human and alive. Here’s to us all....! - Dr. Ron Chioldi Welcome FROM THE CHAIR Spring 2021 marks the end of an academic year unlike any other. It was difficult. It was certainly stressful. So many modifications were made to our normal operating procedures due to the pandemic. Some of these modifications will inform how we operate in the future. Others, I hope we never have to implement ever again. Our faculty, staff, and students were resilient in the face of highly pressurized circum- stances. I want to thank them for their grace, adaptability, and understanding as things constantly changed. Early on in the pandemic, the performing arts were singled out as being particularly risky for infection. We took measures to ensure the safety of our faculty, staff, and students as best we could under state, local, and university protocols. -

HISPANIC MUSIC for BEGINNERS Terminology Hispanic Culture

HISPANIC MUSIC FOR BEGINNERS PETER KOLAR, World Library Publications Terminology Spanish vs. Hispanic; Latino, Latin-American, Spanish-speaking (El) español, (los) españoles, hispanos, latinos, latinoamericanos, habla-español, habla-hispana Hispanic culture • A melding of Spanish culture (from Spain) with that of the native Indian (maya, inca, aztec) Religion and faith • popular religiosity: día de los muertos (day of the dead), santería, being a guadalupano/a • “faith” as expession of nationalistic and cultural pride in addition to spirituality Diversity within Hispanic cultures Many regional, national, and cultural differences • Mexican (Southern, central, Northern, Eastern coastal) • Central America and South America — influence of Spanish, Portuguese • Caribbean — influence of African, Spanish, and indigenous cultures • Foods — as varied as the cultures and regions Spanish Language Basics • a, e, i, o, u — all pure vowels (pronounced ah, aey, ee, oh, oo) • single “r” vs. rolled “rr” (single r is pronouced like a d; double r = rolled) • “g” as “h” except before “u” • “v” pronounced as “b” (b like “burro” and v like “victor”) • “ll” and “y” as “j” (e.g. “yo” = “jo”) • the silent “h” • Elisions (spoken and sung) of vowels (e.g. Gloria a Dios, Padre Nuestro que estás, mi hijo) • Dipthongs pronounced as single syllables (e.g. Dios, Diego, comunión, eucaristía, tienda) • ch, ll, and rr considered one letter • Assigned gender to each noun • Stress: on first syllable in 2-syllable words (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) • Stress: on penultimate syllable in 3 or more syllables (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) Any word which doesn’t follow these stress rules carries an accent mark — é, á, í, ó, étc. -

Harmonic Analysis of Mallet Percussion by Max Candocia Goals

Harmonic Analysis of Mallet Percussion By Max Candocia Goals • Basic understanding of sound waves and mallet percussion • Understand harmonic analysis • Understand difference in sounds of different mallets and striking location Marimba Vibraphone Recording: Vermont Counterpoint, Nathaniel Bartlett Recording: La Fille Aux Cheveux de Lin, Ozone Percussion Ensemble Photo courtesy of vichitex.com Photo courtesy of woodbrass.com Xylophone Recording: Fantasy on Japanese Wood Prints Photo courtesy of onlinerock.com Sound Waves • Vibrating medium (ie. Air, water, ground) • Longitudinal • Harmonics – Sinusoidal Components Sine: Sawtooth: Images courtesy of Wikipedia Qualities of Harmonics • Frequency – Cycles per second (Hertz); determines pitch Photo courtesy of Wikipedia • Amplitude – Power of wave; determines loudness Photo courtesy of physics.cornell.edu • Phase – Location of harmonic relative to other harmonics Photo courtesy of 3phasepower.org Harmonic Analysis Harmonics of Kelon xylophone struck in center with hard rubber mallet Vibraphone HarmonicsDry: Wet: Instrument Mallet Location # Harmonics H1 dB H2 dB H3 dB H4 dB H5 dB Vibraphone Black Dry 5 6 19 0.8 13 3 Vibraphone Black Wet 2 16 1.1 Vibraphone Red Dry 3 22 3.5 1.5 Vibraphone Red Wet 1 1 Vibraphone White Dry 4 16 0.5 9 0.6 Vibraphone White Wet 2 25 1.5 Xylophone Harmonics Instrument Mallet Location # Harmonics H1 Freq H2 Freq H3 Freq H4 Freq H5 Freq Xylophone Hard Rubber Center 4 886.9 1750 2670 5100 Xylophone Hard Rubber Edge 4 886.9 1760 2670 5150 Xylophone Hard Rubber Node 3 886.85