Skirting the Law: Sudan's Post-CPA Arms Flows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War Economy in Karima, Khartoum and Juba, Sudan Bruijn, M.E.De; Brinkman, I.; Bilal, H.; Wani, P.T

The Nile connection : effects and meaning of the mobile phone in a (post)war economy in Karima, Khartoum and Juba, Sudan Bruijn, M.E.de; Brinkman, I.; Bilal, H.; Wani, P.T. Citation Bruijn, M. Ede, Brinkman, I., Bilal, H., & Wani, P. T. (2012). The Nile connection : effects and meaning of the mobile phone in a (post)war economy in Karima, Khartoum and Juba, Sudan. Afrika-Studiecentrum, Leiden. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18450 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18450 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). The Nile Connection. Effects and Meaning of the Mobile Phone in a (Post)War Economy in Karima, Khartoum and Juba, Sudan Mirjam de Bruijn & Inge Brinkman with Hisham Bilal & Peter Taban Wani ASC Working Paper 99 / 2012 African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Telephone +31-71-5273372 Fax +31-71-5273344 Website www.ascleiden.nl E-mail [email protected] © Mirjam de Bruijn & Inge Brinkman The Nile Connection Effects and Meaning of the Mobile Phone in a (Post)War Economy in Karima, Khartoum and Juba, Sudan by Mirjam de Bruijn & Inge Brinkman with Hisham Bilal & Peter Taban Wani Leiden, The Netherlands February 2012 Please do not quote without the consent of the authors Table of Contents Foreword 5 Points of departure 5 Research methodologies 8 Main findings 9 Acknowledgements 11 1. Introduction 13 A vast country 13 Politics and borders 14 History of mobility 16 Box 1. Sending remittances: Old and new 17 Conflict and warfare in Sudan 18 2. -

A Level Geography a Level Geography

Summer Work (Year 11 Induction Programme) A level Geography A Level Geography This booklet contain a range of activities to support your transition from GCSE to A Level. It will help to develop your knowledge and understand of some new geographical themes, and will begin to develop some of the vital skills needed for success at A Level. The list below outlines the tasks, which can be completed in any order. The extra-curricular activities are optional but will support your studies at A Level, and give you an opportunity to focus on your particular interests within geography. Page 1. The Geography of the Americas 3-12 2. Human Rights 13-15 3. Earthquakes and Economic Development 16-18 4. What is the The Geography of my Favourite Place? 19-20 5. Extra-Curricular Activities 21-22 At A Level we follow the OCR specification https://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/223012-specification-accredited-a- level-gce-geography-h481.pdf 1 The American continents (North, Central and South) Task One: Label the listed countries on the map below. Canada Venezuela United States of America Ecuador Guatemala Peru Honduras Chile Nicaragua Brazil Coast Rica Argentina Panama Guyana Colombia French Guiana El Salvador 2 The American continents – physical geography (mountains, rivers and coasts) Task Two: a. Add the Equator, Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn to your map. b. Label the oceans and seas around the American continents (Arctic Ocean, Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico). c. Draw and label the 2 main rivers – Mississippi and Amazon. d. -

1 Name 2 History

Sudan This article is about the country. For the geographical two civil wars and the War in the Darfur region. Sudan region, see Sudan (region). suffers from poor human rights most particularly deal- “North Sudan” redirects here. For the Kingdom of North ing with the issues of ethnic cleansing and slavery in the Sudan, see Bir Tawil. nation.[18] For other uses, see Sudan (disambiguation). i as-Sūdān /suːˈdæn/ or 1 Name السودان :Sudan (Arabic /suːˈdɑːn/;[11]), officially the Republic of the Sudan[12] Jumhūrīyat as-Sūdān), is an Arab The country’s place name Sudan is a name given to a جمهورية السودان :Arabic) republic in the Nile Valley of North Africa, bordered by geographic region to the south of the Sahara, stretching Egypt to the north, the Red Sea, Eritrea and Ethiopia to from Western to eastern Central Africa. The name de- the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African or “the ,(بلاد السودان) rives from the Arabic bilād as-sūdān Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west and Libya lands of the Blacks", an expression denoting West Africa to the northwest. It is the third largest country in Africa. and northern-Central Africa.[19] The Nile River divides the country into eastern and west- ern halves.[13] Its predominant religion is Islam.[14] Sudan was home to numerous ancient civilizations, such 2 History as the Kingdom of Kush, Kerma, Nobatia, Alodia, Makuria, Meroë and others, most of which flourished Main article: History of Sudan along the Nile River. During the predynastic period Nu- bia and Nagadan Upper Egypt were identical, simulta- neously evolved systems of pharaonic kingship by 3300 [15] BC. -

Chris Scurfield Avid/ Premiere Offline

Chris Scurfield Avid/ Premiere Offline Profile Chris is a passionate storyteller who enjoys working across all forms of documentary and drama. With a keen sense of narrative and a good eye for detail, his creative talents are matched by his hardworking ethos, making him a real pleasure to work with! Drama-Doc “American Monster” Season 7. 2 x 60min. Viewers get closer than ever to some of America's most shocking and surprising crimes. Filled with never-before-seen footage of these devils in disguise, American Monster interweaves twisting-turning stories of astonishing crimes, with 'behind-the- scenes' footage of killers at their seemingly most innocent. Arrow Media for Discovery ID “Locked up Abroad” Series 14. 1 x 44min. The film-maker sheds light on the life situations of people who have been arrested while travelling abroad, usually for trying to smuggle illegal drugs out of a particular country. Raw for Channel 5/ National Geographic “Rowell: The Final Verdict” Episode 3 – Silencing Witnesses. 1 x 60min. For the 74th Anniversary of the ‘Roswell Incident’, this 6-part mini-series goes back over the events and eyewitness accounts of the most notorious extra-terrestrial incident in U.S. history. In each episode, harrowing accounts drive an explosive and cinematic minute-by-minute exploration using cutting-edge technology and artificial intelligence to separate fact from fiction. October Films for Discovery+ and Travel “Web of Lies: The Model Predator” Series 7. 1 x 42min. Male teenage athletes, lured into sending nude selfies, find themselves blackmailed and at the mercy of a relentless paedophile. -

Soil and Oil

COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE COALITION FOR I NTERNATIONAL JUSTICE SOIL AND OIL: DIRTY BUSINESS IN SUDAN February 2006 Coalition for International Justice 529 14th Street, N.W. Suite 1187 Washington, D.C., 20045 www.cij.org February 2006 i COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE COALITION FOR I NTERNATIONAL JUSTICE SOIL AND OIL: DIRTY BUSINESS IN SUDAN February 2006 Coalition for International Justice 529 14th Street, N.W. Suite 1187 Washington, D.C., 20045 www.cij.org February 2006 ii COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE © 2006 by the Coalition for International Justice. All rights reserved. February 2006 iii COALITION FOR INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CIJ wishes to thank the individuals, Sudanese and not, who graciously contributed assistance and wisdom to the authors of this research. In particular, the authors would like to express special thanks to Evan Raymer and David Baines. February 2006 iv 25E 30E 35E SAUDI ARABIA ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT LIBYA Red Lake To To Nasser Hurghada Aswan Sea Wadi Halfa N u b i a n S aS D e s e r t ha ah raar a D De se es re tr t 20N N O R T H E R N R E D S E A 20N Kerma Port Sudan Dongola Nile Tokar Merowe Haiya El‘Atrun CHAD Atbara KaroraKarora RIVER ar Ed Damer ow i H NILE A d tb a a W Nile ra KHARTOUM KASSALA ERITREA NORTHERN Omdurman Kassala To Dese 15N KHARTOUM DARFUR NORTHERN 15N W W W GEZIRA h h KORDOFAN h i Wad Medani t e N i To le Gedaref Abéche Geneina GEDAREF Al Fasher Sinnar El Obeid Kosti Blu WESTERN Rabak e N i En Nahud le WHITE DARFUR SINNAR WESTERN NILE To Nyala Dese KORDOFAN SOUTHERN Ed Damazin Ed Da‘ein Al Fula KORDOFAN BLUE SOUTHERN Muglad Kadugli DARFUR NILE B a Paloich h 10N r e 10N l 'Arab UPPER NILE Abyei UNIT Y Malakal NORTHERN ETHIOPIA To B.A.G. -

Fisheries: the Implications of Current Wto Negotiations for Economic Transformation in Developing Countries

FISHERIES: THE IMPLICATIONS OF CURRENT WTO NEGOTIATIONS FOR ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Leah Worrall and Max Mendez-Parra December 2017 FISHERIES: THE IMPLICATIONS OF CURRENT WTO NEGOTIATIONS FOR ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Acknowledgements This paper was written for the discussion in advance of the upcoming 11th WTO Ministerial Conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in December 2017. We are grateful for comments received from Sheila Page from ODI and Vanessa Head and Avi Bram from DFID. The views presented are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of DFID or ODI. Errors are the authors’ own. © SUPPORTING ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION. The views presented in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of DFID or ODI. ii FISHERIES: THE IMPLICATIONS OF CURRENT WTO NEGOTIATIONS FOR ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES CONTENTS List of acronyms __________________________________________________ iv Executive summary _______________________________________________ v 1. Introduction ____________________________________________________ 1 2. Background ___________________________________________________ 3 2.1. Data considerations _____________________________________________________ 3 2.2. Fisheries trade _________________________________________________________ 3 2.2.1. Global capture production ____________________________________________________ 3 2.2.2. Fisheries trade _____________________________________________________________ -

Sudan Attacks on Schools

EDUCATION UNDER ATTACK 2014 COUNTRY PROFILES SUDAN ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS There were different accounts of how many schools More than 1,000 university students were arrested, were attacked during 2009-2012. According to Arry more than 15 killed and more than 450 injured in Organization for Human Rights and Development, 48 2009-2012, mostly in demonstrations on campus or schools were destroyed in attacks by government in education-related protests. Many of the injuries forces in South Kordofan between April 2011 and resulted from security forces using excessive force. February 2012, but it was not specified if these were There were dozens of incidents of attacks on, and targeted attacks.1467 Other UN, human rights and military use of, schools.1457 media reports documented 12 cases of schools or education buildings being destroyed, damaged or CONTEXT looted, including primary and secondary schools and a teacher training institute, in the areas of Darfur, In Sudan’s western region of Darfur, fighting Abyei, Blue Nile and South Kordofan during 2009- between government forces and pro-government 2012, but again it was not specified how many were militia and rebels over the past decade has left targeted.1468 300,000 people dead and more than two million displaced,1458 with schools set on fire and looted and According to the UN, three instances of burning, students and teachers targeted by armed groups.1459 looting and destruction of schools occurred between January 2009 and February 2011.1469 For example, Sudan’s protracted civil war between the -

IN the MATTER of an AD HOC ARBITRATION PCA No. GOS-SPLM 53,391 PURSUANT to the ARBITRATION AGREEMENT in the HAGUE, the NETHERLANDS

IN THE MATTER OF AN AD HOC ARBITRATION PCA No. GOS-SPLM 53,391 PURSUANT TO THE ARBITRATION AGREEMENT IN THE HAGUE, THE NETHERLANDS BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF SUDAN AND THE SUDAN PEOPLE’S LIBERATION MOVEMENT/ARMY THE SUDAN PEOPLE’S LIBERATION MOVEMENT/ARMY REJOINDER 28 February 2009 Table of Contents I. SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...........................................................................................1 A. The Government Has Failed Entirely to Establish that the ABC Experts Exceeded Their Mandate .........................................................................................1 1. The Government’s Reply Memorial Attempts Improperly to Expand the Grounds on which the ABC Experts’ Report May Be Challenged........2 2. Even if they Were Admissible, the Government’s Purported Excess of Mandate Claims Are Frivolous....................................................................4 3. The Government Excluded or Waived Any Rights to Claim that the ABC Experts Exceeded Their Mandate.......................................................6 B. The Government’s Fundamentally Revised Factual Case Confirms the ABC Experts’ Decision and Supports the SPLM/A’s Definition of the Abyei Area .......7 1. The Government’s New Factual Case Confirms that the Area of the Nine Ngok Dinka Chiefdoms Transferred to Kordofan in 1905 Comprises All of the Territory North of the Current Bahr el Ghazal/Kordofan Boundary to Latitude 10º35’N ........................................7 2. The Boundary Between Kordofan and Bahr el Ghazal Was Indefinite and -

RAUL SACRISTAN Editor

For all bookings, please call 020 3143 5769 or email Nasreen RAUL SACRISTAN Editor Skills Off-Line Editing, Visual Narrative & Story-Telling Avid / Premiere / FCP, Current Affairs & Documentaries Credits Discovery + – What Killed Maradona: 1 x 50min The untold story of Diego Maradona's extraordinary life. Interviews with those close to the talented footballer reveal the different factors which may have contributed to his untimely death at 60. ITN Productions NETFLIX – Lost Pirate Kingdom – 2 x 45min The end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713 and around 1720, as many unemployed seafarers took to piracy to make ends meet, when a surplus of sailors after the war led to a decline in wages and working conditions. This revived Caribbean trade provided rich new pickings for a wave of piracy. World Media Rights Discovery Channel (US) & Channel 4 (UK) – Lost Beast Of The Ice Age – 1 x 90min A team of international scientists seek out well-preserved remains of woolly mammoths, woolly rhino, wolves, and cave lions that once roamed Siberia. Working in tunnels dug by locals on the hunt for valuable giant mammoth tusks, their findings may reveal extraordinary new evidence that could lead us closer to answering one of the biggest mysteries of the ice age – what caused the woolly mammoth to go extinct? Renegade Pictures BBC Panorama – Aleppo: Life Under Siege – 1 x 30min Ob-Doc documentary. The battle for Aleppo, Syria's largest city and once home to over two million people, is in its fourth year of civil war. Divided between opposition-held east and government- controlled west, ordinary civilians are suffering on both sides. -

Geography Summer Induction Work

Geography Summer Induction Work At S6C we follow the AQA A Level. The structure of our course is explained in the table below. The topics are categorised as follows: PHYSICAL, HUMAN and NEA. Year 12 Year 13 Topics Water & Carbon Cycles NEA (Independent Changing Places Investigation) Coastal Systems & Global Systems & Governance Landscapes Hazards Population & the Environment In the September of Year 12 we start with Water and Carbon Cycles. We have put the following resources together for you to start doing some reading and watching for the first topic. There is also a short optional project for you to complete which should help you settle in quickly when you start studying Geography at college. You will need to purchase the year 1 textbook - AQA Geography A Level & AS Physical Geography Student Book Paperback – by Simon Ross (Author), Tim Bayliss (Author), Lawrence Collins (Author), Alice Griffiths (Author). It is currently half price on Amazon. Water and Carbon Cycles Water and carbon are fundamental to supporting life on earth and are hence regarded as Earth’s “life support” systems. Water and carbon are cycled in both open and closed systems between the land, oceans and the atmosphere. The processes in the water and carbon cycles are interrelated. In this topic you will study the natural changes in the systems and also how human activity is increasingly threatening and altering water and carbon cycles e.g. through deforestation, ocean acidification and desertification. Principal: Simon Firth (01722 597970) [email protected] www.salisbury6c.ac.uk 66-78 Tollgate Road, Salisbury, SP1 2JJ Salisbury Sixth Form College– part of Magna Learning Partnership, a company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales Number 7865850 – registered office c/o St Edmund’s School, Church Road, Laverstock, Salisbury, SP1 1RD. -

Statement of Media Content Policy 2016.Pdf

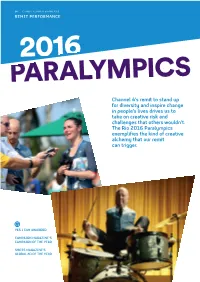

14 CHANNEL 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 REMIT PERFORMANCE 2016 PARALYMPICS Channel 4’s remit to stand up for diversity and inspire change in people’s lives drives us to take on creative risk and challenges that others wouldn’t. The Rio 2016 Paralympics exemplifies the kind of creative alchemy that our remit can trigger. YES I CAN AWARDED: CAMPAIGN MAGAZINE’S CAMPAIGN OF THE YEAR SHOTS MAGAZINE’S GLOBAL AD OF THE YEAR CHANNEL 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 15 2/3 48% OF OUR ON-AIR PRESENTING OF THE UK POPULATION TEAM WERE DISABLED. REACHED WITH OUR PARALYMPIC COVERAGE London 2012 was a watershed moment for Paralympic sport, and the Rio 2016 Paralympics went even further in raising >40m 1.8m the profile of disability sport and positively VIEWS ACROSS ALL SOCIAL APPEARING IN HALF OF THE PLATFORMS. UK’S FACEBOOK FEEDS AND improving public perceptions of disability in WITH OVER 1.8 MILLION SHARES, the UK and around the world. ‘YES I CAN’ WAS THE MOST SHARED OLYMPIC/PARALYMPIC It also established a new international AD GLOBALLY THIS YEAR. benchmark for Paralympics coverage. The UK is now considered an exemplar for its approach to the Games by the International Paralympic Committee and Channel 4 has shared this success story with broadcasters around the world since the 2012 Games. Preparing for Rio 2016 following the success of London 2012 was no small order, however we saw it as more of an opportunity than a risk – because taking creative risks pushes The result was a three-minute film featuring OUR RIO COVERAGE boundaries in the pursuit of positive change, 140 disabled people with a band specifically Taking on the ratings challenge of an away which is part of Channel 4’s DNA. -

2003 Programme Review

About 4 Review of 2003 Statement of Promises In 2003, Channel 4 took the diverse experience of living in Britain now head on. Across its current affairs, drama and satirical entertainment, it mirrored the passions of a society again waking up to political choice. In the range of its contemporary documentary, Without Channel 4’s investment, it is from the enjoyable to the searing, it displayed doubtful whether there would be a significant the uninhibited openness of the personal; in its independent production sector in the UK, and it education programmes it tested the ambiguous would certainly be far less diverse. connections between our present sensibility and the past that shapes and challenges it. Competitive Performance It also placed Britain in perspective in the This has been a challenging year for Channel way it continuously explored and sought to 4 as for other terrestrial channels. Our ratings understand the rest of the world. performance has been resilient in peak time (forecast 9.4% in 2003 versus 9.7% in 2002) Too much public service television retails a but we have lost share in daytime and later soft focus, “heritage” view of Britain, protecting at night. the old and comforting from the modern and dangerous. At its best Channel 4 refused such a Landmarks of 2003 false distinction. The Deal Second Generation Where Channel 4 invented, others followed. Operatunity Programmes pioneered on Channel 4 were The Death of Klinghoffer openly copied by the BBC, ITV and Five. The Hajj – Greatest Trip on Earth Channel 4 now, as much as it ever did, does the Channel 4 News in Iraq original thinking for the rest of British television.