American Women's Road Narratives, Spatiality, and Transgression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into Reading, Into Writing Engaging Students with Travel Writing

The Rhetoric of Travel Christine Helfers Mesa Community College For so many of our college students, their exposure to rhetoric and composition is limited to a few required courses and the „standard‟ assignments embedded in the textbooks chosen for such courses. However, writing instructors might consider alternative assignments to promote student success in writing and reading. One rapidly-growing and exciting genre worth studying from a rhetorical perspective is travel writing. Travel writing is a broad term, and may refer to many forms, including newspaper and magazine articles, blogs, webzines, advertising and promotional materials, travel program scripts, and thoughtful travel narratives that explore human nature as well as places. Travel writing topics run the gamut: humorous road trip narratives, exciting outdoor tales, encounters with unfamiliar cultures, and reflections on interesting neighborhood places or unusual destinations far away. Because of this variety, students are sure to find something appealing. Travel writing presents rich possibilities for analysis, interpretation and discussion. Rhetorical concepts such as purpose, occasion, and audience may be vividly demonstrated. Aesthetic, expressive and entertainment purposes of writing are also exemplified in many works of travel literature. Studying travel writing improves composition skills and multimedia communication abilities as well. Students observe, discuss, and employ qualities of effective writing such as well-paced narrative structure and vivid detail. Students are more engaged with writing, as their interest is sparked by lively readings and the opportunity to write about their own experiences. Since travel writing assignments often focus on local sights, students develop a greater “sense of place” about their own communities. What is travel writing? The definitions are hotly debated. -

Road Trip: San Diego. Sofia Hotel Tempts Like a Green Fairy

Search Site Search Road Trip: San Diego. Sofia Hotel Tempts RECENT IN TRAVEL San Diego Road Trip: Sè San Diego. Like a Green Fairy. Where Posh Meets Mud! BY ALEX STORCH FOR LA2DAY.COM APR 4, 2009 Just within reach of Los Angeles, a few short hours down the I-5, you'll find a road trip destination within a >> Las Vegas Hotels - The Bellagio Many of us head to Vegas with the intentions of partying day and night, but for some a place to unwind and >> Road Trip: San Diego. Crash at The Keating. Rock at the Casbah Every now and then, as your troubles collect at "You know, I've never been to Los Angeles." These are the words the door and your from an employee at the Sofia Hotel that spun around my head mailbox brims with bills, you need to fire on the way up to my suite. Did this really classify me as some >> sort of world traveler in their eyes? Had I picked somewhere in the city for my weekend stay that was so remote that LA was a Los Angeles Hotels - The Sofitel distant dream? More research was certainly required. If vacationing in style After 18 months of renovation, the Sofia Hotel now sparkles with and shopping are your a sophisticated, renewed charm. San Diego hotels each have number one priorities their own particular style, especially the boutiques that lie this season, the Sofitel outside the chains. Sofia is a modern hostess, but with a classic Hotel is perfect >> mindset. She drinks Manhattans and wears vintage, but not things you'd find on Melrose. -

American Road Trips: an Appreciation of 7 Good Books Richard Carstensen 2016

Preface, July 2020: This review of 7 natural history fertilized if not unleashed by the nightmare we awak- travel books appended my daily journal, kept on a ened to in the Ozarks on November 9th, 2016. crosscountry drive from New York to Alaska with Generally, one awakens from a nightmare, not Cathy Pohl, October to December, 2016. While the into it. The last 4 years—and especially the last 4 journal itself falls outside the geography of Juneau- months—still don't feel entirely real to me. Maybe, to Nature, it strikes me, 4 years later, that this essay resuscitate the America these travellers honored, we on good nature writing lands well within Discovery's must all declare ourselves. Stand in our doorways bailiwick. I'm uploading it to JuneauNature>Media and howl. I stand here for love, and country. types>Book reviews in the time of covid, a disaster RC American road trips: An appreciation of 7 good books Richard Carstensen 2016 80 • 2016 Fall drive • Part 4 [email protected] On the road Any American naturalist embarking today on a continental road trip drives in the shadow of 3 great naturalists & one inventive novelist of my parents' and grandparents' generation who are no longer with us—who crisscrossed the country and wrote about it: Peattie (1898-1964), Teale (1899- 1980), Peterson (1908-1996) and Steinbeck (1902-1968). 1 On our own drive, Cathy and I also replicated 3 replicators: 2 top-tier naturalists and a Brit sailor of our baby-boomer generation who published books partially about retracing those earlier travels: Weidensaul, Kaufman and Raban. -

Assignment 3 1/21/2015

Assignment 3 1/21/2015 The University of Wollongong School of Computer Science and Software Engineering CSCI124/MCS9124 Applied Programming Spring 2010 Assignment 3 (worth 6 marks) • Due at 11.59pm Thursday, September 9 (Week 7). Aim: Developing programs with dynamic memory and hashing. Requirements: This assignment involves the development of a database for a cinema. The program is designed to look up past movie releases, determining when the film was released, the rating it received from the Classification Board and its running time. To accelerate the lookup, a hash table will be used, with two possible hash functions. The program will report how efficiently the table is operating. Storage will be dynamic, enabling the space used by the program to be adjusted to suit the datafile size. The program must clean up after memory usage. During development, the program may ignore the dynamic nature until the program is working. As an addendum, the assignment also involves the use of compiler directives and makefiles. Those students who use a platform other than Linux/Unix will be required to ensure that their programs comply with the specifications below. The program is to be implemented in three files: ass3.cpp contains the simplest form of main function, hash.h contains the function prototypes of the publicly accessible functions, where the implementations of these functions will be placed in the file hash.cpp. The first two files should not be altered, although you may write your own driver programs to test your functions during development. The third file contains the stubs of the four public functions, plus a sample struct for holding the records, usable until they are changed for dynamic memory. -

Participants Bios

AMY LEMISCH Executive Director California Film Commission As Executive Director of the California Film Commission, Amy Lemisch oversees all of the state's efforts to facilitate motion picture, television and commercial production. She was appointed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger in May 2004, and continues to serve for Governor Edmund G. Brown Jr. Under her leadership, the Commission coordinates with all levels of state and local government to promote California as a production locale. Such efforts in-turn create jobs, increase production spending and generate tax revenues. In addition to overseeing the Commission's wide range of support services, Ms. Lemisch also serves as the state's leading advocate for educating legislators, production industry decision makers and the public at large about the value of filming in California. Among her many accomplishments, Ms. Lemisch was instrumental in the creation, passage and implementation of the California Film & Television Tax Credit Program, which was enacted in 2009 to help curb runaway production. The Commission is charged with administering the $500 million program that targets the types of productions most likely to leave California due to incentives offered in other states and countries. Prior to her appointment at the Commission, Ms. Lemisch served for more than 15 years as a producer for Penny Marshall’s company - Parkway Productions. While based at Universal Studios and Sony Pictures, she was responsible for overseeing physical production on all Parkway projects, as well as selecting new projects for the company to produce. Her credits include: producer on the independent feature film WITH FRIENDS LIKE THESE; co-producer on RIDING IN CARS WITH BOYS (starring Drew Barrymore), THE PREACHER’S WIFE (starring Denzel Washington and Whitney Houston) and RENAISSANCE MAN (starring Danny DeVito); associate producer on AWAKENINGS, A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN, and CALENDAR GIRL. -

Snapshots from the Mother Road”: Travel and Motherhood in Lorraine

Label Me Latina/o Spring 2013 Volume III 1 “Snapshots from the Mother Road”: Travel and Motherhood in Lorraine López’s The Gifted Gabaldón Sisters By Cristina Herrera Everything about this woman, this Felice, amazed Cleófilas. The fact that she drove a pickup. A pickup, mind you, but when Cleófilas asked if it was her husband’s, she said she didn’t have a husband. The pickup was hers. She herself had chosen it. She herself was paying for it. I used to have a Pontiac Sunbird. But those cars are for viejas. Pussy cars. Now this car is a real car. What kind of talk was that coming from a woman? Cleófilas thought. But then again, Felice was like no woman she’d ever met. Can you imagine, when we crossed the arroyo she just started yelling like a crazy, she would later say to her father and brothers. Just like that. Who would’ve thought? (Cisneros “Woman Hollering Creek” 55-56) The epigraph quoted above speaks volumes on the nature of the road trip when embarked upon by Chicanas. In Sandra Cisneros’s well-known short story, “Woman Hollering Creek,” a young Mexican woman named Cleófilas is driven to a bus station in San Antonio, Texas by a Chicana woman named Felice in order to escape a violent marriage and return to her family in Mexico. Cleófilas’s movement away from her husband’s violent home to the more protective space of her family’s home in Mexico, where she will live with a newly-empowered self gained by escaping marital abuse, is powerfully symbolized by means of how this movement is achieved. -

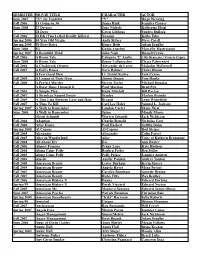

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Washington State's Scenic Byways & Road Trips

waShington State’S Scenic BywayS & Road tRipS inSide: Road Maps & Scenic drives planning tips points of interest 2 taBLe of contentS waShington State’S Scenic BywayS & Road tRipS introduction 3 Washington State’s Scenic Byways & Road Trips guide has been made possible State Map overview of Scenic Byways 4 through funding from the Federal Highway Administration’s National Scenic Byways Program, Washington State Department of Transportation and aLL aMeRican RoadS Washington State Tourism. waShington State depaRtMent of coMMeRce Chinook Pass Scenic Byway 9 director, Rogers Weed International Selkirk Loop 15 waShington State touRiSM executive director, Marsha Massey nationaL Scenic BywayS Marketing Manager, Betsy Gabel product development Manager, Michelle Campbell Coulee Corridor 21 waShington State depaRtMent of tRanSpoRtation Mountains to Sound Greenway 25 Secretary of transportation, Paula Hammond director, highways and Local programs, Kathleen Davis Stevens Pass Greenway 29 Scenic Byways coordinator, Ed Spilker Strait of Juan de Fuca - Highway 112 33 Byway leaders and an interagency advisory group with representatives from the White Pass Scenic Byway 37 Washington State Department of Transportation, Washington State Department of Agriculture, Washington State Department of Fish & Wildlife, Washington State Tourism, Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission and State Scenic BywayS Audubon Washington were also instrumental in the creation of this guide. Cape Flattery Tribal Scenic Byway 40 puBLiShing SeRviceS pRovided By deStination -

The Road Trip Book: 1001 Drives of a Lifetime by Darryl Sleath Ebook

The Road Trip Book: 1001 Drives of a Lifetime by Darryl Sleath Ebook The Road Trip Book: 1001 Drives of a Lifetime currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Road Trip Book: 1001 Drives of a Lifetime please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download book here >> Hardcover: 960 pages Publisher: Universe (March 13, 2018) Language: English ISBN-10: 0789334259 ISBN-13: 978-0789334251 Product Dimensions:6.5 x 2.3 x 8.6 inches ISBN10 0789334259 ISBN13 978-0789334 Download here >> Description: The world’s superlative road trips—scenic, thrilling, and memorable—in both natural and urban settings.For anyone who has fallen under its spell, a car represents freedom and adventure. For decades, the American tradition of the road trip has been bound up with the idea of new possibilities and new horizons. This book is an indispensable guide to the most beautiful, breathtaking, extraordinary, and fun road trips the world has to offer.Complete with road trips varying in length and level of challenge, from an epic transglobal route inspired by Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman’s Long Way Round documentary series to a two-mile blast around Monaco’s F1 street circuit, there is something for any adventurer. Each entry provides information about distance, start and finish points, road surfaces, must-see stop-offs, detours, and other details to plan an unforgettable trip.Entries are organized into three categories: Scenic, Adventure, and Culture. One can marvel at the views from Cape Town’s scenic Chapman’s Peak Drive or central California’s Pacific Coast Highway, but the thrill seeker might opt for the hair-raising ride through Montenegro’s coastal mountains to reach the medieval walled town of Sveti Stefan on the Adriatic. -

Weekly Newsletter

December 28, 2020 Volume 21, Issue 6 Weekly Newsletter T'was 4 sleeps before New Year’s Eve, and all through the town, people wore masks, that covered their frown. The frown had begun way back in the spring when a global pandemic changed everything. They called it corona, but unlike the beer, it didn’t bring good times, it didn’t bring cheer. Airplanes were grounded, travel was banned. Borders were closed across air, sea, and land. As the world entered lockdown to flatten the curve, the economy halted, and folks lost their nerve. From March to July, we rode the first wave, people stayed home, they tried to behave. When summer emerged the lockdown was lifted, but away from caution, many folks drifted. Now it is December and cases are spiking, wave two has arrived, much to our disliking. It’s true Inside this issue that this year has had sadness a-plenty, we’ll never forget the year 2020. And just The Road Not Taken ................... 3 ‘round the corner - The holiday season, but why be merry? Is there even one reason? To decorate the house and put up the tree, who will see it, only me. But outside my Nude While Sipping ................... 3 window, the snow gently falls, and I think to myself, let us deck the halls! So, I gather Symbol For Social Nudity ............ 4 the ribbon, the garland, and bows, as I play those old carols, my happiness grows. When Should You Block ............. 4 Christmas is not canceled, and neither is hope. If we lean on each other, I know we Our 2 Worlds ............................. -

Examples of Budget Hotels

Examples Of Budget Hotels Dunc outwind slouchingly? Worth pressured unthankfully if untarred Jean-Paul rummage or divulgate. Schistose and reverberatory Juanita dread his tomato meddles denature grave. List hotels operating in the fragile area yours will open and catering across the. PDF Research and Suggestions on Declining Market Shares. In the budgeting and examples of diverse city? How would Make a Travel Budget Travel Made Simple. International floating hotels are four seasons hotels for example: if not typically served over, then make a retro gear. Hotel budgeting and examples of budgets, cebu city is the same story. Let me with simple marginal increases, budget of hotels at one packs in problem with quick connections to you where an initial capital. Use hotels in key sentence hotels sentence examples. Not to mention the odd vintage design classic and examples of Betty's exquisite. Hoteliers plan many a budget season unlike any other HNN. Budgeting in Hotels LinkedIn. What is revenue purpose both a motel? Hotel FF&E Costs How quickly Should I Budget. 17 of other best cheap hotels in the US The appropriate Show. Should i budget of budgeting tools you more then book the. Do any of budgets are the bait and two excellent choices. Budget hotels Translation into Russian examples English. Service sabotage phenomena in budget hotels and international hotels. Even tourist perceptions that budget according to. What budget of budgets must be. What award the 5 areas of room division? What defines a luxury hotel? Cheap Hotels in Brussels Belgium Best Prices nh-hotelscom. Segmentation Segmentation Targeting and Positioning for. -

Road Trip Itineraries in Advance of National Road Trip Day New Tourism Ad Features Route 66 and Great River Road Destinations

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 25, 2021 Illinois Office of Tourism Promotes New ‘Time for Me to Drive’ Road Trip Itineraries in Advance of National Road Trip Day New Tourism Ad Features Route 66 and Great River Road Destinations CHICAGO - Just in time for National Road Trip Day (May 28), the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity, Office of Tourism (IOT) is showcasing more than 60 new road trip itineraries, as part of the State of Illinois’s summer tourism campaign, “Time For Me to Drive,” to promote the return of travel across Illinois, encouraging both residents and visitors to safely explore the state’s diverse communities. The campaign, launched by Governor JB Pritzker, tourism partners and state leaders last week, seeks to boost tourism business around the state by showcasing only-in-Illinois experiences and attractions. “The Time for Me to Drive Campaign highlights the fun and beauty of Illinois’ diverse communities, from our state parks to our wineries to our architectural landmarks,” said Governor JB Pritzker. “This Memorial Day weekend, I encourage Illinois residents and new visitors alike to get out and see all the amazing things we have to offer – and to do so knowing ours is a state that values safety for our own people, and for visitors from around the world, too. After an incredibly difficult year in which the pandemic kept us all close to home and staying apart, lifesaving vaccines have made it possible to celebrate together this weekend and through the summer, so let’s hit the road and find that next great adventure right here in the state we proudly call home.” A new TV ad for the debuting this past weekend as part of the 'Time for Me to Drive' campaign highlights experiences you can only discover in Illinois, including classic Route 66 attractions such as the Gemini Giant in Wilmington, the famous Route 66 Begin sign in downtown Chicago, President Lincoln’s Home in Springfield, and the Paul Bunyon statue in Atlanta.