Exploring Design Professionalism in Visual Information Structure of News Websites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Experience Design to Drive Institutional Change, by Matt Glendinning

The Monthly Recharge - November 2014, Experience Design Designing Learning for School Leaders, by Carla Silver Using Experience Design to Drive Institutional Change, by Matt Glendinning Designing the Future, by Brett Jacobsen About L+D Designing Learning for School Leadership+Design is a nonprofit Leaders organization and educational Carla Robbins Silver, Executive Director collaborative dedicated to creating a new culture of school leaders - empathetic, creative, collaborative Dear Friends AND Designers: and adaptable solution-makers who can make a positive difference in a The design industry is vast and wonderful. In his book, Design: rapidly changing world. Creation of Artifacts in Society, Karl Ulrich, professor at Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, includes an We support creative and ever-growing list of careers and opportunities in design. They innovative school leadership at range form the more traditional and known careers - architecture the individual and design, product design, fashion design, interior design - to organizational level. possibilities that might surprise you - game design, food design, We serve school leaders at all news design, lighting and sound design, information design and points in their careers - from experience design. Whenever I read this list, I get excited - like teacher leaders to heads of jump-out-of-my-seat excited. I think about the children in all of our school as well as student schools solving complex problems, and I think about my own leaders. children, and imagine them pursuing these careers as designers. We help schools design strategies for change, growth, Design is, according to Ulrich, "conceiving and giving form to and innovation. -

June 2015 Broadside

T H E A T L A N T A E A R L Y M U S I C ALLIANCE B R O A D S I D E Volume XV # 4 June, 2015 President’s Message Are we living in the Renaissance? Well, according to the British journalist, Stephen Masty, we are still witnessing new inventions in musical instruments that link us back to the Renaissance figuratively and literally. His article “The 21st Century Renaissance Inventor” [of musical instruments], in the journal “The Imaginative Conservative” received worldwide attention recently regard- ing George Kelischek’s invention of the “KELHORN”. a reinvention of Renaissance capped double-reed instruments, such as Cornamuse, Crumhorn, Rauschpfeiff. To read the article, please visit: AEMA MISSION http://www.theimaginativeconservative.org/2015/05/the-21st-centurys-great-renaissance-inventor.html. It is the mission of the Atlanta Early Music Alli- Some early music lovers play new replicas of the ance to foster enjoyment and awareness of the histor- Renaissance instruments and are also interested in playing ically informed perfor- the KELHORNs. The latter have a sinuous bore which mance of music, with spe- cial emphasis on music makes even bass instruments “handy” to play, since they written before 1800. Its have finger hole arrangements similar to Recorders. mission will be accom- plished through dissemina- tion and coordination of Yet the sound of all these instruments is quite unlike that information, education and financial support. of the Recorder: The double-reed presents a haunting raspy other-worldly tone. (Renaissance? or Jurassic?) In this issue: George Kelischek just told me that he has initiated The Capped Reed Society Forum for Players and Makers of the Crumhorn, President ’ s Message page 1 Cornamuse, Kelhorn & Rauschpfeiff. -

Hauntology, the Penumbra, and the Narratives of Play Experience

Hauntology, the Penumbra, and the Narratives of Play Experience Lindsay D. Grace University of Miami, School of Communication Florida, United States of America [email protected] Abstract later in the writing of authors like Kurt Vonnegut. In This paper collects a series of heuristics in game level design to Slaughterhouse Five for example, Vonnegut uses the de- articulate the relationship between designed experience, per- vice of a science fiction – becoming unstuck in time – to ceived experience, and the mechanics of play. This work aims play with the notions of simultaneity [6]. Simultaneity is a simply to illuminate core concepts as a guide for framing the concept, futurist artists employed to provide a sense that relationship between designer/author and player/participant. It is logical spatial relations had been superseded [6]. Like offered simply as a philosophical lens for perceiving and design- Vonnegut’s characters, who see a person’s entire life like a ing the dynamic between created works and their perception by stretch of mountains, from baby legs to geriatric legs, the players. It does so by offering the concept of nested narratives - work of visual simultaneity is a collage of moments in time recursively experienced between the played narrative and the viewed at once. Today, the core computational method for designed narrative. It is an adaptation of Derrida’s Hauntology, such work is iteration and self-reference, the simplest ele- applied to the context of narratives in game design, at the scale ments of the programming convention of recursion. st Recursion, the repeated application of a self-referential and pace of 21 century game design. -

Information Graphics Design Challenges and Workflow Management Marco Giardina, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, Pablo Medi

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Volume: 3 – Issue: 1 – January - 2013 Information Graphics Design Challenges and Workflow Management Marco Giardina, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, Pablo Medina, Sensiel Research, Switzerland Abstract Infographics, though still in its infancy in the digital world, may offer an opportunity for media companies to enhance their business processes and value creation activities. This paper describes research about the influence of infographics production and dissemination on media companies’ workflow management. Drawing on infographics examples from New York Times print and online version, this contribution empirically explores the evolution from static to interactive multimedia infographics, the possibilities and design challenges of this journalistic emerging field and its impact on media companies’ activities in relation to technology changes and media-use patterns. Findings highlight some explorative ideas about the required workflow and journalism activities for a successful inception of infographics into online news dissemination practices of media companies. Conclusions suggest that delivering infographics represents a yet not fully tapped opportunity for media companies, but its successful inception on news production routines requires skilled professionals in audiovisual journalism and revised business models. Keywords: newspapers, visual communication, infographics, digital media technology © Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies 108 Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Volume: 3 – Issue: 1 – January - 2013 During this time of unprecedented change in journalism, media practitioners and scholars find themselves mired in a new debate on the storytelling potential of data visualization narratives. News organization including the New York Times, Washington Post and The Guardian are at the fore of innovation and experimentation and regularly incorporate dynamic graphics into their journalism products (Segel, 2011). -

Website Management

Website management: A course of study for strategic communication students Christine Clark Perry A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Lois Boynton, Ph.D. Heidi Hennink-Kaminski, Ph.D. Ron Bergquist, Ph.D. © 2010 Christine Clark Perry ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT CHRISTINE CLARK PERRY: Website management: A course of study for strategic communication students (Under the direction of Lois Boynton, Ph.D.) Strategic communicators are increasingly called upon to evaluate, maintain, and improve websites. Yet, journalism and mass communication schools are not adequately preparing students to assume the role of website manager. This thesis presents evidence of the need for a website management course and offers a solution for professional graduate and upper-level undergraduate students studying public relations, advertising, or marketing. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the patience, love, and support of my husband, Vernon, who took care of me and our home during my years in graduate school. He has been my rock, and I thank him deeply. I would also like to thank my advisor and committee chair, Lois Boynton, for her guidance and enthusiasm for my project; my other committee members, Heidi Hennink- Kaminski and Ron Bergquist, for their helpful contributions; and all of the journalism and mass communication professors who directly or indirectly influenced my work. Ramona DuBose and other leaders at the public health school also supported my studies and allowed me to flex work hours around my schoolwork. -

COLLEGE of DESIGN Newsspring 2004

NC STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF DESIGN news SPRING 2004 Angelo Abbate Karen E. DeWitt Jean Marie Livaudais Dr. Fatih Rifki PROFESSOR OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE HEAD OF HARRYE B. LYONS DESIGN LIBRARY DIRECTOR OF PROFESSIONAL RELATIONS, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE Carla Abramczyk Lope Max Díaz EXTERNAL RELATIONS ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR GRADUATE STUDIES DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ART + DESIGN Austin Lowrey Laurie Ringaert EXTERNAL RELATIONS Ed Driggers PROFESSOR EMERITUS OF GRAPHIC DESIGN DIRECTOR, CENTER FOR UNIVERSAL DESIGN Matthew Arion ACCOUNTING TECHNICIAN Meghan Lurowist Jackie Robertson COMPUTING CONSULTANT, STUDENT SERVICES ASSISTANT ADMINISTRATIVE SECRETARY INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY LABORATORY Richard Duncan COORDINATOR OF TRAINING IN UNIVERSAL DESIGN Fernando Magallanes Michael Rodrigues Delsey Avery RESEARCH, EXTENSION AND ENGAGEMENT ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF LANDSCAPE BUDGET MANAGER ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT, DEAN'S OFFICE Cheryl Eatmon ARCHITECTURE Henry Sanoff FACULTY & STAFF Kermit Bailey ADMINISTRATIVE SECRETARY, Marvin J. Malecha PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF GRAPHIC DESIGN INDUSTRIAL DESIGN AND GRAPHIC DESIGN DEAN PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE Dr. Kristen Schaffer Dr. Donald A. Barnes Jeremy Ficca ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE PROFESSOR EMERITUS OF ARCHITECTURE ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE Joe McCoy COORDINATOR OF NETWORK & HARDWARE Martha Scotford Thomas Barrie Patrick FitzGerald SERVICES, PROFESSOR OF GRAPHIC DESIGN DIRECTOR OF SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ART -

EJ to Review Marina Plans

www.citizenandj g Proud he areas since 1881 www.lyndasrealestateservice.com iMkmmmiim Members of the Boyne Boyne City bands per City High School at Walt Disney World band wait in the LAKE BUENA thousands that lined the have performed at the re- Florida VISTA— The Boyne City streets of the Magic King- sort since its opening. The sunshine High School marching dom, waiting for the pa- program has expanded just prior to band members strutted rade, were surprised to since that time, and perfor- the start of their stuff down Main hear the announcement of mance opportunities are the Disney Street, U.S.A. at the Walt the band. Several guests open to bands, orchestras, Dreams Disney World Resort in had lined up for the parade choirs, drill teams, dance Come True Jan. 29. The band traveled up to an hour in advance. ensembles and other per- parade. The to take part in Disney The Boyne City High forming groups. band Magic Music Days and School Jazz Band became Groups come from performed perform for an interna- stars of their own Disney throughout the world to for an tional audience of park show when they took the perform, learn and com- interna- guests. stage at Cosmic Ray's pete at all four theme tional The group performed Starlight Cafe, located in- parks. audience of prior to the "Disney side of Magic Kingdom. For information visit guests at Dreams Come True" pa- High school and middle ww\vJ3isreytefoimingAits.OTrn the park. or call 1-800-603-0552. Blazers rade. The school marching bands Courtesy photo The Boyne City boys varsity basketba!! team out Community scored Kalkaska EJ to review iness 50-48 in a Lake enrichment Michigan Confer- ence victory at marina plans classes Boyne City on firm. -

Newspaper Design J 464/564 | WINTER TERM | STEVEN ASBURY

NEWSPAPER DESIGN J 464/564 | WINTER TERM | STEVEN ASBURY Winter 2013, Tu-Th, 4:00-5:50 p.m. • Color: Basic color theory, how to build a color palette and Steven Asbury how to get sophisticated, professional-looking results. Office hours: By appointment. E-mail: [email protected] Philosophy Website: http://jcomm.uoregon.edu/~sasbury News design is about information as much as decoration. Think of yourselves as visual journalists, not Books just decorators. You’ll be the newsroom experts on how The Newspaper Designer’s Handbook 7th ed., to combine text, graphics and photos to explain stories to Tim Harrower, (McGraw-Hill, 2007). readers. Note: If you already have the 6th edition, that should work fine. Grading Amazon.com is offering free 2-day shipping for students. Grades will be based on the following formula: Participation/Discussion * 25% Software/Labs Design projects/in-class exercises 25% The majority of the coursework will require you to create Quizzes 25% pages using Adobe InDesign and/or Quark XPress. It is very Final project ** 25% important that you take the time to learn these programs early in the course as several class exercises will require you * At the beginning of each class, you’ll be asked to show an to use this software to create pages “on deadline.” example of an outstanding page design. This can be a page from a local paper, a magazine, or found online. Course overview The class will cover ... Attendance is mandatory, and it’s important that you • News design: Learn how to manage breaking-news design. -

AMY TAN Membership Hotline: 800-898-1065 May 2021 Volume XLVIII, Number 11 WILL AM-FM-TV: 217-333-7300 Campbell Hall 300 N

Friends of WILL Membership Magazine May 2021 AMERICAN MASTERS: AMY TAN Membership Hotline: 800-898-1065 May 2021 Volume XLVIII, Number 11 WILL AM-FM-TV: 217-333-7300 Campbell Hall 300 N. Goodwin Ave., Urbana, IL 61801-2316 Mailing List Exchange Donor records are proprietary and confidential. WILL does not sell, rent or trade its donor lists. Patterns Friends of WILL Membership Magazine Editor/Art Designer: Sarah Whittington Art Director: Kurt Bielema Printed by Premier Print Group. Printed with SOY INK on RECYCLED, RECYCLABLE paper. RADIO 90.9 FM: A mix of classical music and NPR in- formation programs, including local news. (Also with live streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See pages 4-5. 101.1 FM and 90.9 FM HD2: Locally produced music programs and classical music from C24. (101.1 is available in the Champaign-Urbana Back on March 26, Illinois Public Media released area.) See page 6. a statement in support of the Asian, Asian Ameri- 580 AM: News and information, NPR, BBC, can, and Pacific Islander communities in response news, agriculture, talk shows. (Also heard to the appalling uptick in violent acts of racism on 90.9 FM HD3 with live streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See page 7. directed at them since the pandemic began. As we acknowledge in the statement, anti-Asian rhetoric and acts are nothing new and can be seen and TELEVISION felt throughout our collective history. To our Asian, WILL-HD Asian American, and Pacific Islander friends, we see All your favorite PBS and local programming, in high definition when available. -

Basic Design Faculty Member: Laura Johnston

Script: Basic Design Faculty member: Laura Johnston Slide 1: Basics of news design: Building better pages from the beginning. Slide 2: Technology, in part, helped create modern design by allowing newspapers to begin reproducing photographs. Slide 3: Adding color to news pages also changed the look of the printed page. Modern readers want a way to engage with their news and be part of an experience, not just see words on a page. Slide 4: These pages of the Columbia Missourian show how design has changed within the last century, with the introduction of color, modular layout and other elements that help attract a reader’s eyes to a page. Slide 5: Before you can begin thinking of news pages as complete packages, you need to know what you’re working with. These four elements: photos, cutlines, headlines and text are part of every design – or should be. There will be instances when designers don’t have all of these elements to work with on a page, but skill and flexibility will help you consider other options. Slide 6: While some of these terms are used only when talking about a front page, others appear on nearly every page of a newspaper. It’s important to know the correct terms so you can tell others what you need to complete your design. Slide 7: Because most newspapers are filled with columns of text, it’s important to know about typography. The way type is measured helps share important information to a designer. Staff designers should choose a typeface for their designs that allows some flexibility with weight, such as bold or italics, but typefaces should be consistent from page to page. -

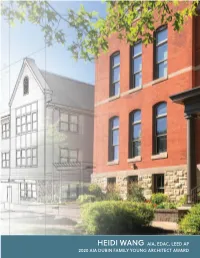

Heidi Wang, AIA Their Website for Additional Information

HEIDI WANG AIA, EDAC, LEED AP 2020 AIA DUBIN FAMILY YOUNG ARCHITECT AWARD HEIDI WANG AIA, EDAC, LEED AP Partner - Worn Jerabek Wiltse Architects, P.C. Education: 2002 Illinois State University - Bachelor of Arts Interior Design, Art History, Construction Administration 2007 University of Illinois at Chicago Master of Architecture AIA Gold Medal Recipient 2010 University of Illinois at Chicago Master of Science in Health Design Professional Experience: 2007 -> Worn Jerabek Wiltse Architects, P.C., Chicago, IL Partner - 2018 - Present Associate Partner - 2015-2018 2005-2007 FGM Architects and Planners, Oakbrook, IL Architectural Intern 2002-2004 University of Wisconsin Madison, Medical School, WI Associate Facilities Planning Specialist Licensure / Affiliations: State of Illinois Licensed Architect #001-021591 State of Indiana Licensed Architect #AR11600158 State of Michigan Licensed Architect #1301067855 State of Wisconsin Licensed Architect #12723-5 State of South Carolina Licensed Architect #10161 AIA Member NCARB Accredited LEED AP EDAC Certified Affordable Assisted Living Coalition Member Illinois Housing Council Member and Membership Committee SAGE Member Volunteerism: 2008 -> AIA Design for Aging KC - Co-Chair 2019 -> Illinois Housing Council - Membership Committee 2017 -> Hope Manor Village - Community Garden Project 2011-2013 Architecture for Humanity - Art on Sedgwick Community Art Center - Nyegina Library - Tanzania Development Support 2013 Tanzania Development Support - Library Build Trip 2012-2013 AIA / CPS “Barbie I Can Be...” - Facilitator 01 HEIDI WANG AIA, EDAC, LEED AP Partner - Worn Jerabek Wiltse Architects, P.C. PERSONAL STATEMENT Many architects would describe our profession as a passion. Architecture is for me something much more powerful — it gives me purpose and definition. In the early days of my career, I was drawn to the idea that design had immense power to improve the lives of people, from building occupants to community members. -

Orange County, Virginia Route 3 Corridor Planning Charrette Report

Orange County, Virginia Route 3 Corridor Planning Charrette Report of Findings & Recommendations Prepared by: 2220 Bryan Park Avenue Richmond, VA 23228 (804) 347-1877 Table of Contents Charrette Panel and Team Members 3 Introduction & Overview 4 The Charrette Process 4 The Study Area 6 Panel Assignment 7 Summary of Findings 9 Community Assets 9 Community Challenges 9 Service Provider Interview Summaries 10 Stakeholder Feedback 13 Summary of Recommendations 14 The Vision 16 Phase 1 17 Phase 2 18 Phase 3 20 Phase 4 21 Questions & Answers Market Potential 22 Planning & Design 23 Development Strategies 24 Implementation 26 Final Thoughts & Words of Wisdom 27 Panel Bios 28 About Spectrum Growth Solutions 32 Acknowledgements 32 Appendices 1 – Stakeholder Questionnaires 33 2 – Summary of Stakeholder Interviews 37 Spectrum Growth Solutions Route 3 Master Planning Charrette Report Page 2 Charrette Panel Members and Project Support Panel Chair Panel Director Erich Strohhacker, PE, PTOE Faith V. McClintic Transportation Leader Principal Bowman Consulting Group, Inc. Spectrum Growth Solutions LLC Richmond, Virginia Richmond, Virginia Panel Members Project Support Herman G. Diebler, Jr. Martina Arel Principal Research Manager Verity Commercial, LLC Spectrum Growth Solutions LLC Reston, Virginia Richmond, Virginia Kevin Humphrey Maria Prince President Project Manager The Patina Group Spectrum Growth Solutions LLC Richmond, Virginia Richmond, Virginia Branch P. Lawson President – Hampton Roads Division East West Communities Suffolk, Virginia Frederick