Literary Criticism of Shakespeare's King Lear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JBC Book Clubs Discussion Guide Created in Partnership with Picador Jewishbookcouncil.Org

JBC Book Clubs Discussion Guide Created in partnership with Picador Jewishbookcouncil.org Jewish Book Council Contents: 20th Century Russia: In Brief 3 A Glossary of Cultural References 7 JBC Book Clubs Discussion Questions 16 Recipes Inspired by The Yid 20 Articles of Interest and Related Media 25 Paul Goldberg’s JBC Visiting Scribe Blog Posts 26 20th Century Russia: In Brief After the Russian Revolution of 1917 ended the Czar- Stalin and the Jews ist autocracy, Russia’s future was uncertain, with At the start of the Russian Revolution, though reli- many political groups vying for power and ideolog- gion and religiosity was considered outdated and su- ical dominance. This led to the Russian Civil War perstitious, anti-Semitism was officially renounced (1917-1922), which was primarily a war between the by Lenin’s soviet (council) and the Bolsheviks. Bolsheviks (the Red Army) and those who opposed During this time, the State sanctioned institutions of them. The opposing White Army was a loose collec- Yiddish culture, like GOSET, as a way of connecting tion of Russian political groups and foreign nations. with the people and bringing them into the Commu- Lenin’s Bolsheviks eventually defeated the Whites nist ideology. and established Soviet rule through all of Russia un- der the Russian Communist Party. Following Lenin’s Though Stalin was personally an anti-Semite who death in 1924, Joseph Stalin, the Secretary General of hated “yids” and considered the enemy Menshevik the RCP, assumed leadership of the Soviet Union. Party an organization of Jews (as opposed to the Bolsheviks which he considered to be Russian), as Under Stalin, the country underwent a period of late as 1931, he continued to condemn anti-Semitism. -

Cordelia''s Portrait in the Context of King Lear''s

Paula M. Rodríguez Gómez Cordelias Portrait in the Context of King Lears... 181 CORDELIAS PORTRAIT IN THE CONTEXT OF KING LEARS INDIVIDUATION* Paula M. Rodríguez Gómez** Abstract: This analysis attempts to show the relations between the individual psyche and the contents of the collective unconscious. Following Von Franzs analytical technique, the tragic action in King Lear will be read as an individuation process that will rescue archetypal contents and solve existential paradoxes that cause an imbalance between the ego and the self, leading to self-destruction. Once communication is eased and balance is restored, the transformation-seeking process that engaged the design of the play itself becomes resolved, and events can be led to a conventional tragic resolution. Jungian analysis will therefore provide a critical framework to unveil the subconscious contents that tear the character of the king between annihilation and survival, the anima complex that affects the king, responding thus for the action of the play and its centuries-old success. Keywords: collective unconscious, myth, individuation, archetype, tragedy, anima. Resumen: Este análisis pretende sacar a la luz las relaciones entre la psyche individual y los contenidos del inconsciente colectivo. Siguiendo la técnica analítica de Von Franz, la acción trágica de King Lear será entendida a través del proceso de individuación que revierte sobre los contenidos arquetípicos y resuelve las paradojas existenciales que cau- san el desequilibrio entre ego y self. Una vez que la comunicación es facilitada y el equilibrio psíquico recuperado, el proceso transformativo que afecta la génesis de la trama se resuelve y el argumento alcanza una resolución convencional. -

Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas. Lise Brandt Pedersen Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pedersen, Lise Brandt, "Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2159. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2159 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I 72- 17,797 PEDERSEN, Lise Brandt, 1926- SHAVIAN .SHAKESPEARE:' SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, XEROXA Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan tT,TITn ^TnoT.r.a.A'TTAItf U4C PPPM MT PROPTT.MF'n FVAOTT.V AR RECEI VE D SHAVIAN SHAKESPEARE: SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Lise Brandt Pedersen B.A., Tulane University, 1952 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1963 December, 1971 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to thank Dr. -

Sources of Lear

Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Lynne Bradley, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) Abstract The temptation to meddle with Shakespeare has proven irresistible to playwrights since the Restoration and has inspired some of the most reviled and most respected works of theatre. Nahum Tate’s tragic-comic King Lear (1681) was described as an execrable piece of dementation, but played on London stages for one hundred and fifty years. David Garrick was equally tempted to adapt King Lear in the eighteenth century, as were the burlesque playwrights of the nineteenth. In the twentieth century, the meddling continued with works like King Lear’s Wife (1913) by Gordon Bottomley and Dead Letters (1910) by Maurice Baring. -

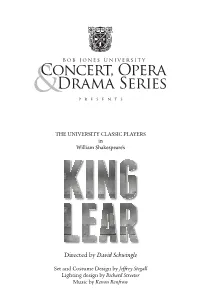

Directed by David Schwingle

THE UNIVERSITY CLASSIC PLAYERS in William Shakespeare’s Directed by David Schwingle Set and Costume Design by Jeffrey Stegall Lighting design by Richard Streeter Music by Kenon Renfrow CAST OF CHARACTERS DIRECTOR’S NOTES Lear, King of Britain ......................................................................... Ron Pyle It is a fearful thing to write about Shakespeare (brief let me be!). The fear increases when one approaches the Goneril, Lear’s eldest daughter ............................................................... Erin Naler towering achievement that is King Lear. The wheel turns a bit more toward a paralyzed state if one considers Duke of Albany, Goneril’s husband ................................................... Harrison Miller the laden, ceremonial barge of relevant scholarship on the subjects. (Imagine entering a room and seeing Oswald, Goneril’s steward ............................................................. Nathan Pittack the eminent Shakespeare scholar, Emma Smith, or our local Spenser and Shakespeare scholar, Ron Horton, Regan, Lear’s second daughter ............................................................ Emily Arcuri comfortably seated, smiling at you!) And yet, though surrounded by giants on every side, some of Lear’s own Duke of Cornwall, Regan’s husband ..................................................... Alex Viscioni making, King Lear pushes on, so I’ll push on and pen a few words about Lear, language, and love. Cordelia, Lear’s youngest daughter .................................................... -

Akira Kurosawa's Lear: Ran and the Failure of the Samurai Ethic

1 Akira Kurosawa’s Lear: Ran and the Failure of the Samurai Ethic “Cineaste: You mentioned in an interview in a Japanese magazine that in Ran you wanted to depict a man’s karma from a “heavenly” viewpoint. Will you elaborate? Akira Kurosawa: I did not exactly say that. Japanese reporters always misunderstand or conveniently summarize what I really say. What I meant was that some of the essential scenes of this film are based on my wondering how God and Buddha, if they actually exist, perceive this human life, this mankind stuck in the same absurd behavior patterns. Kagemusha is made from the viewpoint of one of Kagemusha [shadow warrior—ed.] who sees the specific battles which he is involved in, and moreover the civil war period in general, from a very circumscribed point of view. This time, in Ran, I wanted to suggest a larger viewpoint . more objectively. I did not mean that I wanted to see through the eyes of a heavenly being. I believe that the world would not change even if I made a direct statement: do this and do that. Moreover, the world will not change unless we steadily change human nature itself and our very way of thinking. We have to exorcise the essential evil in human nature, rather than presenting concrete solutions to problems or directly depicting social problems. Therefore, my films might have become more philosophical.” + + + Just as Kurosawa reworked Shakespeare’s Macbeth in his Throne of Blood and reworked the main themes and characters of Hamlet in The Bad Sleep Well, Kurosawa in the last phase of his career chose to rework King Lear in his film Ran (or “Chaos”). -

Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff | the American Conservative

10/26/2017 Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff | The American Conservative BLOGS POLITICS WORLD CULTURE EVENTS NEW URBANISM ABOUT DONATE The Right’s Redeeming the Happy Birthday, I Fought a War How Saddam Ezra Pound, Shutting Up The Strangene Biggest Wedge Debauched Hillary Against Iran— Hussein Locked Away Richard Spencer of ‘Stranger Issue: Donald Falstaff and It Ended Predicted Things’ Trump Badly America’s Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff Do not moralize---there is a little of Shakespeare's 'Fat Knight' in all of us. By ALLEN MENDENHALL • October 26, 2017 Like 3 Share Tweet Falstaff und sein Page, by Adolf Schrödter, 1866 (Public Domain). Falstaff: Give Me Life (Shakespeare’s Personalities) Harold Bloom, Scribner, 176 pages. In The Daemon Knows, published in 2015, the heroic, boundless Harold Bloom claimed to have one more book left in him. If his contract with Simon & Schuster is any indication, he has more work than that to complete. The effusive 86-year-old has agreed to produce a sequence of five books on Shakespearean personalities, presumably those with whom he’s most enamored. The first, recently released, is Falstaff: Give Me Life, which has been called an “extended essay” but reads more like 21 ponderous essay-fragments, as though Bloom has compiled his notes and reflections over the years. The result is a solemn, exhilarating meditation on Sir John Falstaff, the cheerful, slovenly, degenerate knight whose unwavering and ultimately self- destructive loyalty to Henry of Monmouth, or Prince Hal, his companion in William Shakespeare’s Henry trilogy (“the Henriad”), redeems his otherwise debauched character. http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/redeeming-the-debauched-falstaff/ 1/4 10/26/2017 Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff | The American Conservative Except Bloom doesn’t see the punning, name-calling Falstaff that way. -

Descendants of Llyr King Lear

Descendants of Llyr King Lear Generation 1 1. LLYR KING1 LEAR was born in 10 AD in Abt,,British Columbia,Canada. He died in 10 AD in AD,,,. He married PENARDIM CELTIC. She was born in Judea, , British Columbia, Canada. Llyr King Lear and Penardim Celtic had the following child: 2. i. BRAN THE2 BLESSED (son of Llyr King Lear and Penardim Celtic) was born in 21 AD in Monmothshire, , , England. He died in 1936 in Monmothshire, , , England. He married ENYGEUS BEN JOSEPH. She was born in Ad, Maluku, Indonesia. She died in Ely, Cambridgeshire, , England. Generation 2 2. BRAN THE2 BLESSED (Llyr King1 Lear) was born in 21 AD in Monmothshire, , , England. He died in 1936 in Monmothshire, , , England. He married ENYGEUS BEN JOSEPH. She was born in Ad, Maluku, Indonesia. She died in Ely, Cambridgeshire, , England. Bran The Blessed and Enygeus Ben Joseph had the following children: 3. i. CARADOC THE3 SILURES (son of Bran The Blessed and Enygeus Ben Joseph) was born in Trevan, Llanilid, Glamorganshire, England. He died in Avalon, Cape May, New Jersey, United States. He married LIVING VENISSA. ii. CARADOC CARACTACUS OF SILURIA (son of Bran The Blessed and Enygeus Ben Joseph) was born in 1980 in Siluria, , , England. He died in 1954 in Rome, Roma, Lazio, Italy. iii. KING OF THE SILURES CARADOC (son of Bran The Blessed and Enygeus Ben Joseph) was born in 65 AD in Trevan,Llanilid,Glamorganshire,. He died in Rome,,,. Generation 3 3. CARADOC THE3 SILURES (Bran The2 Blessed, Llyr King1 Lear) was born in Trevan, Llanilid, Glamorganshire, England. -

King Lear and the Catholic Drama of Three Households and Four Loves

Ken Colston King Lear and the Catholic Drama of Three Households and Four Loves “That word love, which greybeards call divine.” henry vi, part iii Hardly anyone now reads the world’s greatest work of literature for its dramatization of Catholic wisdom. By the 1960s, according to R. A. Foakes, critical opinion had crowned King Lear as Shake- speare’s greatest play, and it is still indeed common to hear it main- tained that Lear is the greatest work of literature ever written in any language. Foakes attributes this rise mainly to the apocalyptic and nihilistic mood of the Cold War. And yet during the same period, he points out, the accepted reading of Lear changed from that of a play concerned with a “pilgrimage to redemption” to one offering “Shake- speare’s bleakest and most despairing vision of suffering, all hints of consolation undermined or denied.”1 It is not surprising that a nihilistic, skeptical age would see only nihilism and skepticism in King Lear. To be sure, the play has some of the ugliest, darkest minutes in all of literature: two ungrateful daugh- ters strip their aged father of his property and drive him outdoors unprotected into a raging storm as he declines into raving madness; a betrayed spy of the state has both eyes gouged out on stage, one logos 16:4 fall 2013 16 logos in cruel jest; a father reconciled to his only loving daughter finds her hanged right after their reconciliation, and another father suffers from a broken heart when he learns that he has wronged his loving son; throughout it all, the cosmic order seems indifferent and even hostile. -

The Tragedy of King Lear

The Tragedy of King Lear by William Shakespeare An Electronic Classics Series Publication 2 The Tragedy of King Lear is a publication of The Elec- tronic Classics Series. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any pur- pose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State University nor Jim Manis, Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any respon- sibility for the material contained within the docu- ment or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. The Tragedy of King Lear by William Shakespeare, The Electronic Classics Series, Jim Manis, Editor, PSU- Hazleton, Hazleton, PA 18202 is a Portable Docu- ment File produced as part of an ongoing publica- tion project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them. Jim Manis is a faculty member of the English Depart- ment of The Pennsylvania State University. This page and any preceding page(s) are restricted by copyright. The text of the following pages are not copyrighted within the United States; however, the fonts used may be. Copyright © 1997 - 2013 The Pennsylvania State University is an equal opportunity University. 3 The Tragedy of KING LEAR by William Shakespeare: His true Chronicle Historie of the life and death of King Lear and his three daughters. With the unfortunate life of Edgar, sonne and heire to the Earle of Gloster, and his sullen and assumed humor of Tom of Bedlam: 4 DRAMATIS PERSONAE LEAR, King of Britain KING OF FRANCE DUKE OF BURGUNDY DUKE OF CORNWALL DUKE OF ALBANY EARL OF KENT EARL OF GLOUCESTER EDGAR: Son to Gloucester. -

![The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear As Inscriptive Site John Rempel](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3600/the-history-of-king-lear-1681-lear-as-inscriptive-site-john-rempel-1643600.webp)

The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear As Inscriptive Site John Rempel

Document generated on 09/29/2021 12:39 a.m. Lumen Selected Proceedings from the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies Travaux choisis de la Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site John Rempel Theatre of the world Théâtre du monde Volume 17, 1998 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1012380ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1012380ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle ISSN 1209-3696 (print) 1927-8284 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Rempel, J. (1998). Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site. Lumen, 17, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.7202/1012380ar Copyright © Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle, 1998 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 3. Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site From Addison in 1711 ('as it is reformed according to the chimerical notion of poetical justice, in my humble opinion it has lost half its beauty') to Michael Dobson in 1992 (Shakespeare 'serves for Tate .. -

Bardolatry and Parody in Baz Luhrmann’S William Shakespeare’S Romeo+Juliet

Streitmann, Ágnes: Bardolatry or Parody? angolPark Popular Cinematic Reconceptualization of the seas3.elte.hu/angolpark Shakespearean Drama: © Streitmann, Ágnes, ELTE BTK: seas3.elte.hu/angolpark Ágnes Streitmann: Bardolatry or Parody? Popular Cinematic Reconceptualization of the Shakespearean Drama Shakespearean cultural history, a kind of interpretative process of reconceptualization or reinvention, has always been shaped by the cultural interests, values and developments of particular historical moments. At the end of the Millennium it was obviously the cinema, a medium of mass entertainment, which became one of the dominant factors in redefining Shakespeare’s late twentieth-century cultural image. The 1990s witnessed the greatest boom in the number of Anglo-American films based on Shakespeare’s plays in the hundred-year history of the medium, and this revitalization of the Shakespeare-film had several significant consequences. First, Shakespeare gained a new prominence in the cultural imagination of the mass audience; second, Shakespearean filmmaking became a crucial element of modern cinema culture, and established itself as big business. Hollywood mainstream film laid claim to the Bard, the emblematic figure of high culture, and produced exciting “Shakespop”1 hybrids, which, as the term Shakespop would suggest, involve a kind of strained but really productive interplay between two cultural systems, high and popular culture. This paper intends to highlight what kind of filmic language these popular appropriations of Shakespeare employ to actualize his works, and how they relate to bardic authority: whether they quote Shakespeare with the aim of parody, homage or simple imitation. Spectacle of Multiplicity – Shakespeare in Hollywood The 1990s proved to be an exciting period in the history of Shakespeare on the screen.