Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:511 Jinja District for FY 2018/19. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Accounting Officer, Jinja District Date: 30/10/2018 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 5,039,582 2,983,815 59% Discretionary Government Transfers 4,063,070 1,063,611 26% Conditional Government Transfers 35,757,925 9,198,562 26% Other Government Transfers 2,554,377 432,806 17% Donor Funding 564,000 0 0% Total Revenues shares 47,978,954 13,678,794 29% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Planning 183,102 22,472 21,722 12% 12% 97% Internal Audit 132,830 32,942 27,502 25% 21% 83% Administration 6,994,221 1,589,106 1,385,807 23% 20% 87% Finance 1,399,200 320,632 310,572 23% 22% 97% Statutory Bodies 995,388 234,790 160,795 24% 16% 68% Production and Marketing 1,435,191 -

Assessment Form

Local Government Performance Assessment Jinja District (Vote Code: 511) Assessment Scores Accountability Requirements % Crosscutting Performance Measures 81% Educational Performance Measures 82% Health Performance Measures 79% Water & Environment Performance Measures 89% 511 Accountability Requirements 2019 Jinja District No. Summary of requirements Definition of compliance Compliance justification Compliant? Annual performance contract 1 Yes LG has submitted an annual performance contract of the • From MoFPED’s The Annual Performance forthcoming year by June 30 on the basis of the PFMAA inventory/schedule of LG Contract of the forth coming year and LG Budget guidelines for the coming financial year. submissions of performance was submitted on 8th July 2019 contracts, check dates of within the adjusted submission submission and issuance of date of 31st August, 2019 receipts and: o If LG submitted before or by due date, then state ‘compliant’ o If LG had not submitted or submitted later than the due date, state ‘non- compliant’ • From the Uganda budget website: www.budget.go.ug, check and compare recorded date therein with date of LG submission to confirm. Supporting Documents for the Budget required as per the PFMA are submitted and available 2 Yes LG has submitted a Budget that includes a Procurement • From MoFPED’s inventory of The LG submitted the approved Plan for the forthcoming FY by 30th June (LG PPDA LG budget submissions, check Budget Estimates that included a Regulations, 2006). whether: Procurement Plan for the FY 2019/20 on 8 thJuly, 2019 thus o The LG budget is accompanied being within the adjusted time by a Procurement Plan or not. -

Micro- MIS Project

IITA CMIS Micro- MIS Project Funded by CTA Second Progress Report January - March 2001 Compiled by: G. Okoboi and S. Ferris Micro market Information Service-Uganda Quarterly report 2 Jan – Mar 2001 Table of contents Page Table of contents........................................................................................................................ 1 List of tables...............................................................................................................................2 Summary and introduction.........................................................................................................3 Project implementation ..............................................................................................................4 Data collection ...........................................................................................................................4 Data input and transfer ...............................................................................................................4 Data processing and dissemination............................................................................................ 4 Radio coverage ...........................................................................................................................5 Financing of radio airtime..........................................................................................................6 Assisting farmers link with other markets .................................................................................6 -

Kakira Outgrowers: Their Success Stories Royal Visit to Paraa Safari

Madhvani Group Magazine Volume 21 No. 1 January 2013 Madhvani Foundation receives prestigious award from H.E. President Museveni Royal visit to Paraa Safari Lodge Kakira Outgrowers: Their success stories When it comes to protecting AGRO INDUSTRY + 254 020214415/17, 722205407 Kakira Sugar Ltd. Excel Construction Ltd. Email:[email protected] your product and image both P.O Box 121, Jinja, Uganda P O Box 1202, Jinja Uganda Website: www.marasa.net Tel. 041 444000 Tel: 041 4221996/ 4505959 Fax: 041 444333/6 Fax: 043 4123150/ 041 4220482 Mara Leisure Camp E-mail: [email protected] E-mail:[email protected] P. O. Box 48995-00100 Inside and outside... Web site: www.kakirasugar.com [email protected] Nairobi, Kenya Website: www.excelconstruction.org + 254 020214415/17, 722205407 Kakira Sweets and Confectioneries Email:[email protected] P O Box 121, Jinja Uganda TOURISM Website: www.marasa.net Tel. 041 4444000 Mweya Safari Lodge Fax: 041 4444110 P O Box 22827, Kampala Uganda GROUP SERVICES E-mail: kakirasweets@kakirasweets. Tel: 031 2260260/1 Muljibhai Madhvani & Co. Ltd. com Fax: 041 4340056 P O Box 54, Jinja Uganda Lodge Tel. No. 041 4340054 Tel. 042 4121218/4120511 Mwera/ Nakigalala Tea Estates Lodge Fax No. 041 4340056 Fax: 043 4123174 P O Box 6361, Kampala, Uganda E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Tel. 075 2799888 Website: www.marasa.net Fax 041 4269399 Madhvani Group Projects Division E-mail: [email protected] Paraa Safari Lodge P O Box 6361 Kampala Uganda [email protected] P O Box 22827, Kampala Uganda Tel: 041 4259390/4/5 [email protected] Tel: 031 2260260/1 Fax: 041 4259399 Fax: 041 4340056 E-mail: [email protected] Kajjansi Roses Ltd. -

Kyambogo University National Merit Admission 2019-2020

KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE COURSE CODE AFD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U1223/539 BALABYE Alice Esther 2018 F U 16 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.9 2 U1223/589 NANYONJO Jovia 2018 F U 85 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.7 3 U0801/501 NAKIMBUGE Kevin 2018 F U 55 NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 45.9 4 U1688/510 TUMWESIGE Hilda Sylivia 2018 F U 34 KYADONDO SS 45.8 5 U1224/536 AKELLO Jovine 2018 F U 31 ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 45.8 6 U0083/693 TUKASHABA Catherine 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.7 7 U1609/503 OTHIENO Tophil 2018 M U 54 NAALYA SSS 45.7 8 U0046/508 ATUHAIRE Comfort 2018 F U 123 MARYHILL HIGH SCHOOL 45.6 9 U2236/598 NABULO Gorret 2018 F U 52 ST.MARY'S COLLEGE, LUGAZI 45.6 10 U0083/541 BEINOMUGISHA Izabera 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.5 KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF VOCATIONAL STUDIES IN AGRICULTURE WITH EDUCATION COURSE CODE AGD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0059/548 SSEGUJJA Emmanuel 2018 M U 97 BUSOGA COLLEGE, MWIRI 33.2 2 U1343/504 AKOLEBIRUNGI Cecilia 2018 F U 30 AVE MARIA SECONDARY SCHOOL 31.7 3 U3297/619 KIYIMBA Nasser 2018 M U 51 BULOBA ROYAL COLLEGE 31.4 4 U1476/577 KIRYA Brian 2018 M U 93 RAINBOW HIGH SCHOOL, BUDAKA 31.2 5 U0077/619 KIZITO -

Archives of the Bishop of Uganda

Yale University Library Yale Divinity School Library Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 Christine Byaruhanga 2007 Revised: 2010-02-03 New Haven, Connecticut Copyright © 2007 by the Yale University Library. Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 - Page 2 Table of Contents Overview 11 Administrative Information 11 Provenance 11 Information about Access 11 Ownership & Copyright 11 Cite As 11 Historical Note 12 Description of the Papers 12 Arrangement 13 Collection Contents 14 Series I. Administrative/Governing Bodies, 1911-1965 14 Church Missionary Society (CMS) 14 CMS Africa Secretary and General (London), 1955-1961 14 CMS East Africa Volume 1, 1953-1957 15 Dioceses 31 Uganda Diocese 31 Deanery Council Minutes 31 Diocesan Association of the Uganda Diocese 32 Diocesan Boards of the Uganda Diocese 34 Diocesan Council of the Uganda Diocese 35 Upper Nile Diocese 37 Diocesan Council of the Upper Nile Diocese (Book), 1955-1969 37 Diocesan Boards of Finance of the Upper Nile Diocese (Book), 1955-1962 37 Diocese of the Upper Nile 37 Ankole/Kigezi Diocese 39 Rural Deaneries 41 Deanery of Ankole 41 Ankole 41 Mbarara 41 Ecclesiastical Correspondences 42 Buganda 43 Deanery of Buddu 43 Deanery of Bukunja 44 Deanery of Bulemezi 45 Deanery of Busiro 46 Deanery of Bwekula 46 Deanery of Gomba 48 Deanery of Kako 49 Archives of the Bishop of Uganda UCU-RG1 - Page 3 Deanery of Kooki 49 Deanery of Kyagwe 49 Deanery of Mengo 50 Deanery of Ndeje 50 Deanery of Singo 51 Bunyoro 52 Deanery of Bunyoro 52 Busoga 54 Deanery of Busoga 54 Toro/Fort Portal 55 -

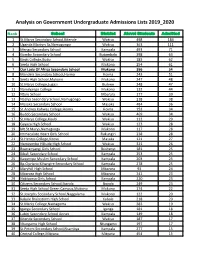

Analysis on Government Undergraduate Admissions Lists 2019 2020

Analysis on Government Undergraduate Admissions Lists 2019_2020 Rank School District Alevel Students Admitted 1 St.Marys Secondary School,Kitende Wakiso 498 184 2 Uganda Martyrs Ss,Namugongo Wakiso 363 111 3 Mengo Secondary School Kampala 493 71 4 Gombe Secondary School Butambala 398 63 5 Kings College,Budo Wakiso 183 62 6 Seeta High School Mukono 254 61 7 Our Lady Of Africa Secondary School Mukono 396 54 8 Mandela Secondary School,Hoima Hoima 243 51 9 Seeta High School,Mukono Mukono 247 48 10 St.Marys College,Lugazi Buikwe 248 47 11 Namilyango College Mukono 132 44 12 Ntare School Mbarara 177 39 13 Naalya Secondary School,Namugongo Wakiso 218 38 14 Masaka Secondary School Masaka 484 36 15 St.Andrea Kahwas College,Hoima Hoima 153 34 16 Buddo Secondary School Wakiso 469 34 17 St.Marys College,Kisubi Wakiso 112 29 18 Gayaza High School Wakiso 123 28 19 Mt.St.Marys,Namagunga Mukono 117 28 20 Immaculate Heart Girls School Rukungiri 238 28 21 St.Henrys College,Kitovu Masaka 121 27 22 Namirembe Hillside High School Wakiso 321 26 23 Bweranyangi Girls School Bushenyi 181 25 24 Kibuli Secondary School Kampala 253 25 25 Kawempe Muslim Secondary School Kampala 203 25 26 Bp.Cipriano Kihangire Secondary School Kampala 278 25 27 Maryhill High School Mbarara 93 24 28 Mbarara High School Mbarara 241 23 29 Nabisunsa Girls School Kampala 220 23 30 Citizens Secondary School,Ibanda Ibanda 249 23 31 Seeta High School Green Campus,Mukono Mukono 174 22 32 St.Josephs Secondary School,Naggalama Mukono 122 20 33 Kabale Brainstorm High School Kabale 218 20 34 St.Marks -

Uganda at Work Newsletter 1St Semester 2019 – Issue #3

Uganda at work Newsletter 1st semester 2019 – Issue #3 ©FAO/A.Ayebazibwe FAO launches new projects to improve climate change adaptation, food security and livelihoods in Uganda Together with the Government of Uganda, through the Ministries of Gender, Labour and Social Development, Water and Environment, Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries, a new five-year programme for Karamoja and West Nile, was launched. The project, “Climate Resilient Livelihood Opportunities for Women Economic Empowerment” (CRWEE) is funded by the Government of Sweden and will strengthen gender-responsive and climate change resilience of rural women, who depend on agricultural production systems. ©FAO In this issue, read about highlights of the launch of the Message from FAO Representative second phase of the Global Climate Change Alliance (GCCA+): Scaling up agriculture adaptation to climate Dear Reader, change in Uganda project, with generous funding from the European Union. Also read about FAO’s transformational Greetings from FAO Representation in Uganda! work through provision of water for production and promoting climate change adaptation among farmers. I welcome you to this issue of our newsletter in which we share updates on some of our work in Uganda. This year, I thank the Government of Uganda and partners for We marked 40 years of partnership with the Government the good relations with FAO and we commit to working of Uganda and continue the commitment to support together for a #ZeroHunger Uganda. Uganda achieve food security for all citizens. Happy Reading Over the last couple of months, we have launched new initiatives and projects aimed at improving livelihoods, Antonio Querido building resilience to shocks and impacts of climate change, improving food and nutrition security and supporting basic social services in different parts of the country. -

Stratplanfinal31st Aug.Pdf

Uganda Peoples Congress Uganda House, Plot 8-10 Kampala Road P.O. Box 37047, Kamapala Tel. +256 312 108551 Website: www.upcparty.net © Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC), 2011 All rights reserved Uganda Peoples Congress Strategic Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................................ iii 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Brief History of the Party ............................................................................... 1 1.2 Achievements and Challenges: ...................................................................... 2 2.0 UPC Party Ideology ........................................................................................ 6 3.0 VISION AND MISSION .................................................................................... 7 4.0 FROM CHALLENGE TO HOPE. ........................................................................ 7 4.1. A Comparative Analysis of UPC Performance in the 2011 National Elections vis-a-vis 2006 ................................................................................................. 8 5.1. STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 1: IMPROVE INTERNAL PARTY ORGANIZATION AND STRUCTURES .................................................................................................. 16 5.2. STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 2: IMPROVE INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL COMMUNICATION SYSTEMS. ...................................................................................................... -

Education and Sports Sector Annual Budget Monitoring Report FY2019/20

EDUCATION AND SPORTS SECTOR ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 NOVEMBER 2020 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug MOFPED #DoingMore Education and Sports Sector: Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2019/20 1 EDUCATION AND SPORTS SECTOR ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 NOVEMBER 2020 MOFPED #Doing TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..............................................................................................ii FOREWORD......................................................................................................................................... iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER ONE: BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Education and Sports Sector Objective .............................................................................................. 1 1.3 Sector Outcomes and Priorities .................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................ 2 2.1. Scope ................................................................................................................................................ -

Hybrid Etlearning for Rural Secondary Schools In

SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN UGANDA SECONDARY HYBRID E.LEARNING FOR RURAL ABSTRACT For the last two decades, a number of policies ai- months in 2007 and they were independently exa- med at increasing participation of female students mined four times. The repeated measures data HYBRID E-LEARNING FOR RURAL in higher education have been implemented by that were collected were analysed using multilevel Uganda Government. However, the participation methods to establish the effects of the hybrid e- SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN UGANDA of female students in the engineering courses in learning intervention and school contexts on the Makerere University, Uganda’s biggest University, performance of the students in external exami- CO-EVOLUTION IN TRIPLE HELIX PROCESSES has remained between 17% to 20% only. Further- nations. more, over 90% of the female engineering stu- dents are from the ‘elite’ and advantaged urban Results of the analysis showed that, 41% of the schools located in the capital city, Kampala, and its students passed and were eligible for university surrounding Districts of Mukono and Wakiso. Ru- admission. Furthermore, it was found that within- ral secondary schools perform poorly in Physics student factors were chiefly responsible for the and Mathematics; the key technology and engine- performance of students in Physics, while for Mat- ering subjects. One rural District, which has failed hematics, the school contexts were more domi- Peter Okidi Lating to send female students to Makerere University nant. However, after extrapolation of the perfor- for engineering training, is Arua- a remote, poor mance of the students over twelve months, up to and insecure District in the West Nile Region of 72% of the students would have passed and be Uganda. -

Government Secondary Schools SN School District EMIS CODE

Government Secondary Schools SN School District EMIS CODE 1 ABIM S.S ABIM 4527 2 LOTUKE SEED S.S ABIM 188003 3 MORULEM GIRLS' S.S ABIM 188000 4 BIYAYA S.S.S ADJUMANI 11990 5 ALERE S.S.S ADJUMANI 418011 6 ADJUMANI S.S.S ADJUMANI 12016 7 DZAIPI S.S ADJUMANI 12034 8 OFUA S.S ADJUMANI 418002 9 ST MARY ASSUMPTA S.S.S ADJUMANI 12058 10 ADILANG SECONDARY SCHOOL AGAGO 4145 11 PATONGO S.S AGAGO 4153 12 ST CHARLES LWANGA AGAGO 4187 13 LIRA PALWO S.S AGAGO 4221 14 OMOT SECONDARY SCHOOL AGAGO 518015 15 AKWANG S.S AGAGO 518013 16 ST THERESA GIRLS SS ALEBTONG 4958 17 OMORO SS ALEBTONG 5019 18 AKII BUA COMP.SS ALEBTONG 208004 19 FATIMA ALOI COMP.GIRLS SS ALEBTONG 208026 20 ALOI SS ALEBTONG 4980 21 APALA SS ALEBTONG 5013 22 AGWINGIRI GIRL'S SCHOOL AMOLATAR 4908 23 AMOLATAR SS AMOLATAR 4911 24 ALEMERE COMPREHENSIVE SS AMOLATAR 208023 25 APUTI SS AMOLATAR 4888 26 AWELO SS AMOLATAR 4897 27 NAMASALE SEED SS AMOLATAR 690000 28 POKOT SS AMUDAT 268000 29 ST PAUL ABARILELA SS AMURIA 660000 30 AMURIA SS AMURIA 12423 31 MORUNGATUNY SSS AMURIA 660001 32 ORUNGO HIGH SCHOOL AMURIA 12432 33 ST PETERS SS AMURIA AMURIA 12456 34 JOHN ELURU MEM SS AMURIA 448017 35 ST FRANCIS ACUMET AMURIA 12473 36 LABIRA GIRLS SS AMURIA 12488 37 LWANI MEMORIAL COLLEGE AMURU 68006 38 KEYO SS AMURU 1432 39 ST MARY'S COLLEGE LACOR AMURU 1430 40 PABBO SS AMURU 1437 41 ADUKU S.S APAC 74 42 IKWERA GIRLS S.S APAC 82 43 CHAWENTE S.S APAC 92 44 INOMO S.S APAC 101 45 NAMBIASO AGRO S.S APAC 106 46 AKOKORO S.S APAC 121 47 APAC S.S APAC 148 48 CHEGERE S.S APAC 156 49 IBUJE S.S APAC 176 50 ADUMI SS