Mwiri in a Time of Change, 1963-7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:511 Jinja District for FY 2018/19. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Accounting Officer, Jinja District Date: 30/10/2018 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 5,039,582 2,983,815 59% Discretionary Government Transfers 4,063,070 1,063,611 26% Conditional Government Transfers 35,757,925 9,198,562 26% Other Government Transfers 2,554,377 432,806 17% Donor Funding 564,000 0 0% Total Revenues shares 47,978,954 13,678,794 29% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Planning 183,102 22,472 21,722 12% 12% 97% Internal Audit 132,830 32,942 27,502 25% 21% 83% Administration 6,994,221 1,589,106 1,385,807 23% 20% 87% Finance 1,399,200 320,632 310,572 23% 22% 97% Statutory Bodies 995,388 234,790 160,795 24% 16% 68% Production and Marketing 1,435,191 -

Ministry of Health

UGANDA PROTECTORATE Annual Report of the MINISTRY OF HEALTH For the Year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 Published by Command of His Excellency the Governor CONTENTS Page I. ... ... General ... Review ... 1 Staff ... ... ... ... ... 3 ... ... Visitors ... ... ... 4 ... ... Finance ... ... ... 4 II. Vital ... ... Statistics ... ... 5 III. Public Health— A. General ... ... ... ... 7 B. Food and nutrition ... ... ... 7 C. Communicable diseases ... ... ... 8 (1) Arthropod-borne diseases ... ... 8 (2) Helminthic diseases ... ... ... 10 (3) Direct infections ... ... ... 11 D. Health education ... ... ... 16 E. ... Maternal and child welfare ... 17 F. School hygiene ... ... ... ... 18 G. Environmental hygiene ... ... ... 18 H. Health and welfare of employed persons ... 21 I. International and port hygiene ... ... 21 J. Health of prisoners ... ... ... 22 K. African local governments and municipalities 23 L. Relations with the Buganda Government ... 23 M. Statutory boards and committees ... ... 23 N. Registration of professional persons ... 24 IV. Curative Services— A. Hospitals ... ... ... ... 24 B. Rural medical and health services ... ... 31 C. Ambulances and transport ... ... 33 á UGANDA PROTECTORATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Annual Report For the year from 1st July, 1960 to 30th June, 1961 I.—GENERAL REVIEW The last report for the Ministry of Health was for an 18-month period. This report, for the first time, coincides with the Government financial year. 2. From the financial point of view the year has again been one of considerable difficulty since, as a result of the Economy Commission Report, it was necessary to restrict the money available for recurrent expenditure to the same level as the previous year. Although an additional sum was available to cover normal increases in salaries, the general effect was that many economies had to in all be made grades of staff; some important vacancies could not be filled, and expansion was out of the question. -

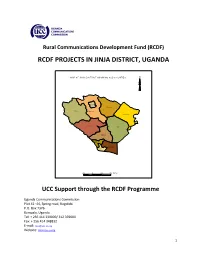

Rcdf Projects in Jinja District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN JINJA DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F JINJA DIS TR ICT S HO W ING S UB CO U NTIES N B uw enge T C B uy engo B uta gaya B uw enge Bus ed de B udon do K ak ira Mafubira Mpum udd e/ K im ak a Masese/ Ce ntral wa lukub a Div ision 20 0 20 40 Kms UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....………3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..………4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….……….…...4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……....5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Jinja district………………l….…….….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Jinja district………..………………….………………....…….14 10- Map of Jinja district showing sub counties………..…………………………………..15 11- Table showing the population of Jinja district by sub counties……………….15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Jinja District…………………………………….………..…..…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. -

Assessment Form

Local Government Performance Assessment Jinja District (Vote Code: 511) Assessment Scores Accountability Requirements % Crosscutting Performance Measures 81% Educational Performance Measures 82% Health Performance Measures 79% Water & Environment Performance Measures 89% 511 Accountability Requirements 2019 Jinja District No. Summary of requirements Definition of compliance Compliance justification Compliant? Annual performance contract 1 Yes LG has submitted an annual performance contract of the • From MoFPED’s The Annual Performance forthcoming year by June 30 on the basis of the PFMAA inventory/schedule of LG Contract of the forth coming year and LG Budget guidelines for the coming financial year. submissions of performance was submitted on 8th July 2019 contracts, check dates of within the adjusted submission submission and issuance of date of 31st August, 2019 receipts and: o If LG submitted before or by due date, then state ‘compliant’ o If LG had not submitted or submitted later than the due date, state ‘non- compliant’ • From the Uganda budget website: www.budget.go.ug, check and compare recorded date therein with date of LG submission to confirm. Supporting Documents for the Budget required as per the PFMA are submitted and available 2 Yes LG has submitted a Budget that includes a Procurement • From MoFPED’s inventory of The LG submitted the approved Plan for the forthcoming FY by 30th June (LG PPDA LG budget submissions, check Budget Estimates that included a Regulations, 2006). whether: Procurement Plan for the FY 2019/20 on 8 thJuly, 2019 thus o The LG budget is accompanied being within the adjusted time by a Procurement Plan or not. -

Factors Affecting the Utilization of Antenatal Care Services by Pregnant Mothers in Jinja Regional Referral Hospital, Jinja District

FACTORS AFFECTING THE UTILIZATION OF ANTENATAL CARE SERVICES BY PREGNANT MOTHERS IN JINJA REGIONAL REFERRAL HOSPITAL, JINJA DISTRICT BY MWINDA RICHARD BMS/0021/133/DU A RESEARCH DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLINICAL MEDICINE AND DENTISTRY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY OF KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY WESTERN CAMPUS JULY 2018 a DECLARATION I hereby declare to the best of my knowledge that this dissertation is my original work and has never been submitted to any institution of higher learning for any undergraduate of post graduate academic award. Where the works of other people has been included, acknowledgement to this has been made to the text and references. Name: Mwinda Richard Date ……………………… Signature……………… i ii DEDICATION I dedicate this research to my mother, Mrs. Nakaima Robinah, sisters, Cathy and Christine, beloved brother Shaw Dickerson and the entire Dickerson family for the love and support rendered to me to accomplish my studies. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank the Almighty God for enabling me put together this piece of work. To my supervisor, Dr. Nyolia James for his commitment and guidance during and throughout the entire research period. I appreciate the efforts of Mrs. Mirembe Josephine from the records Department, Jinja Regional Referral Hospital for the willingness and support while undertaking this study. iv TABLE OF CONTENT DECLARATION ......................................................................................................................................... -

Croc's July 1.Indd

CLASSIFIED ADVERTS NEW VISION, Monday, July 1, 2013 57 BUSINESS INFORMATION MAYUGE SUGAR INDUSTRIES LTD. SERVICE Material Testing EMERGENCY VACANCIES POLICE AND FIRE BRIGADE: Ring: 999 or 342222/3. One of the fastest developing and THE ONLY 6. BOILER ATTENDANT - 3 Posts Africa Air Rescue (AAR) 258527, MANUFACTURER OF SULPHURLESS SUGAR IN Boiler Attendant Certificate Holders with 3-5 258564, 258409. EAST AFRICA based in Uganda. The organization yrs working experience preferred (Thermo ELECTRICAL FAILURE: Ring is engaged in the manufacturing of “Nile Sugar” fluid handling) UMEME on185. and soon starting the manufacturing of Extra 7. SR. ELECTRICAL & INSTRUMENTATION ENGR. MATERIAL TESTING AND SURVEY EQUIPMENT Water: Ring National Water and Neutral Alcohol Invites applications for below - 1Post Sewerage Corporation on 256761/3, 242171, 232658. Telephone inquiry: posts; B.E.(electrical & instrumentation) or equallent Material Testing UTL-900, Celtel 112, MTN-999, 112 1. SHIFT CHEMIST FOR DISTILLATION - 3 Posts with experience of 15 years FUNERAL SERVICES Must have 3-5 years of experience in PLC/ 8. ELECTRICAL ENGR - 1 Post Aggregates impact Value Kampala Funeral Directors, SKADA system independent operation . Diploma in Electrical Engr.or equallent with Apparatus Bukoto-Ntinda Road. P.O. Box 9670, Qualification :-B.SC.Alco,Tech or Diploma in exp of 5 yrs Flakiness Gauge&Flakiness Chem Eng. 9. INSTRUMENTATION ENGR. - 1 Post Kampala. Tel: 0717 533533, 0312 Sleves 533533. 2. LABORATORY CHEMIST SHIFT - 3 Posts Diploma in Instrumentation or equallent with Los Angeles Abrasion Machine Uganda Funeral Services For Mol Analysis /Spirit Analysis /Q.C exp of 5 yrs H/Q 80A Old Kira Road, Bukoto Checking/Spent wash loss checking etc 10. -

Micro- MIS Project

IITA CMIS Micro- MIS Project Funded by CTA Second Progress Report January - March 2001 Compiled by: G. Okoboi and S. Ferris Micro market Information Service-Uganda Quarterly report 2 Jan – Mar 2001 Table of contents Page Table of contents........................................................................................................................ 1 List of tables...............................................................................................................................2 Summary and introduction.........................................................................................................3 Project implementation ..............................................................................................................4 Data collection ...........................................................................................................................4 Data input and transfer ...............................................................................................................4 Data processing and dissemination............................................................................................ 4 Radio coverage ...........................................................................................................................5 Financing of radio airtime..........................................................................................................6 Assisting farmers link with other markets .................................................................................6 -

Kakira Outgrowers: Their Success Stories Royal Visit to Paraa Safari

Madhvani Group Magazine Volume 21 No. 1 January 2013 Madhvani Foundation receives prestigious award from H.E. President Museveni Royal visit to Paraa Safari Lodge Kakira Outgrowers: Their success stories When it comes to protecting AGRO INDUSTRY + 254 020214415/17, 722205407 Kakira Sugar Ltd. Excel Construction Ltd. Email:[email protected] your product and image both P.O Box 121, Jinja, Uganda P O Box 1202, Jinja Uganda Website: www.marasa.net Tel. 041 444000 Tel: 041 4221996/ 4505959 Fax: 041 444333/6 Fax: 043 4123150/ 041 4220482 Mara Leisure Camp E-mail: [email protected] E-mail:[email protected] P. O. Box 48995-00100 Inside and outside... Web site: www.kakirasugar.com [email protected] Nairobi, Kenya Website: www.excelconstruction.org + 254 020214415/17, 722205407 Kakira Sweets and Confectioneries Email:[email protected] P O Box 121, Jinja Uganda TOURISM Website: www.marasa.net Tel. 041 4444000 Mweya Safari Lodge Fax: 041 4444110 P O Box 22827, Kampala Uganda GROUP SERVICES E-mail: kakirasweets@kakirasweets. Tel: 031 2260260/1 Muljibhai Madhvani & Co. Ltd. com Fax: 041 4340056 P O Box 54, Jinja Uganda Lodge Tel. No. 041 4340054 Tel. 042 4121218/4120511 Mwera/ Nakigalala Tea Estates Lodge Fax No. 041 4340056 Fax: 043 4123174 P O Box 6361, Kampala, Uganda E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Tel. 075 2799888 Website: www.marasa.net Fax 041 4269399 Madhvani Group Projects Division E-mail: [email protected] Paraa Safari Lodge P O Box 6361 Kampala Uganda [email protected] P O Box 22827, Kampala Uganda Tel: 041 4259390/4/5 [email protected] Tel: 031 2260260/1 Fax: 041 4259399 Fax: 041 4340056 E-mail: [email protected] Kajjansi Roses Ltd. -

The Case of Internally Displaced Persons in Jinja, Uganda

C OPING WITH D ISPLACEMENT THE CASE OF INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN JINJA, UGANDA Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy Thesis Submitted by Sandra I. Sohne 28 April 2006 © 2006 Sandra I. Sohne http://fletcher.tufts.edu Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks to all of those who made this research possible. My thanks go to the Mellon-MIT Interuniversity Program on NGOs and Forced Migration, the Office of Career Services at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and the Alan Shaw Feinstein International Famine Center at the Friedman School of Nutrition at Tufts University for funding this research. I would like to thank Friends of Orphans for hosting the Tufts Uganda Internship Program in Uganda and providing us with access to Acholi Internally Displaced Persons in Jinja, and Kirk Lange, Arthur Serota and David Manyonga for their guidance, feedback and support. Without the help of and partnership with members of the research team - Lenore Hickey, Sarah Arkin, Diana Nimerovsky, Adrienne Van Nieuwenhuizen, and Jonathan Pourzal - designing the questionnaire and conducting the interviews would not have been possible. Their attention to detail, incredible energy and dedication was inspiring. My thanks go to Carl Jackson who designed the community assessment project, led the research team to gather information about the communities and created the diagrams attached in the appendix of this thesis. Very special thanks go to the individuals in the Jinja communities who opened their homes to the research team and shared their stories with us. I owe them a debt of gratitude for their willingness to speak to us with candor and give us some insight into their lives in Jinja. -

Kyambogo University National Merit Admission 2019-2020

KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE COURSE CODE AFD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U1223/539 BALABYE Alice Esther 2018 F U 16 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.9 2 U1223/589 NANYONJO Jovia 2018 F U 85 SEETA HIGH SCHOOL 47.7 3 U0801/501 NAKIMBUGE Kevin 2018 F U 55 NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 45.9 4 U1688/510 TUMWESIGE Hilda Sylivia 2018 F U 34 KYADONDO SS 45.8 5 U1224/536 AKELLO Jovine 2018 F U 31 ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 45.8 6 U0083/693 TUKASHABA Catherine 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.7 7 U1609/503 OTHIENO Tophil 2018 M U 54 NAALYA SSS 45.7 8 U0046/508 ATUHAIRE Comfort 2018 F U 123 MARYHILL HIGH SCHOOL 45.6 9 U2236/598 NABULO Gorret 2018 F U 52 ST.MARY'S COLLEGE, LUGAZI 45.6 10 U0083/541 BEINOMUGISHA Izabera 2018 F U 50 IMMACULATE HEART GIRLS SCHOOL 45.5 KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2019/2020 ACADEMIC YEAR The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme: BACHELOR OF VOCATIONAL STUDIES IN AGRICULTURE WITH EDUCATION COURSE CODE AGD INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0059/548 SSEGUJJA Emmanuel 2018 M U 97 BUSOGA COLLEGE, MWIRI 33.2 2 U1343/504 AKOLEBIRUNGI Cecilia 2018 F U 30 AVE MARIA SECONDARY SCHOOL 31.7 3 U3297/619 KIYIMBA Nasser 2018 M U 51 BULOBA ROYAL COLLEGE 31.4 4 U1476/577 KIRYA Brian 2018 M U 93 RAINBOW HIGH SCHOOL, BUDAKA 31.2 5 U0077/619 KIZITO -

Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations

UGANDA NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations a Uganda National Academy of Sciences A4 Lincoln House Makerere University P.O. Box 23911, Kampala, Uganda Tel: +256-414-53 30 44 Fax: +256-414-53 30 44 E-mail: [email protected] www.ugandanationalacademy.org This is a report of the Uganda National Academy of Sciences (UNAS). UNAS works to achieve improved prosperity and welfare for the people of Uganda by generating, SURPRWLQJVKDULQJDQGXVLQJVFLHQWL¿FNQRZOHGJHDQGE\JLYLQJHYLGHQFHEDVHGDGYLFH to government and civil society. UNAS was founded in 2000 and was granted a Charter E\+LV([FHOOHQF\WKH3UHVLGHQWRI8JDQGDLQ,WLVDQKRQRUL¿FDQGVHUYLFHRULHQWHG RUJDQL]DWLRQ IRXQGHG RQ SULQFLSOHV RI REMHFWLYLW\ VFLHQWL¿F ULJRU WUDQVSDUHQF\ PXWXDO respect, linkages and partnerships, independence, and the celebration of excellence. All rights reserved. Except as otherwise permitted by written agreement, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior permission of the copyright owner, the Uganda National Academy of Sciences. Suggested citation: UNAS, CDDEP, GARP-Uganda, Mpairwe, Y., & Wamala, S. (2015). Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations (pp. 107). Kampala, Uganda: Uganda National Academy of Sciences; Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy. ISBN: 978-9970-424-10-8 © Uganda National Academy of Sciences, August 2015 Antibiotic Resistance in Uganda: Situation Analysis and Recommendations i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS $QWLPLFURELDOUHVLVWDQFH $05 KDVEHHQFODVVL¿HGDVDJOREDOKHDOWKWKUHDWWKDWWKUHDWHQV the gains achieved by anti-infectives. The world is therefore coming together to mobilize efforts to combat the problem. -

Planned Shutdown March 2021

PLANNED SHUTDOWN FOR MARCH 2021 SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT AND ROUTINE MAINTENANCE REGION DAY DATE SUBSTATION FEEDER/PLANT PLANNED WORK DISTRICT AREAS & CUSTOMERS TO BE AFFECTED North Eastern Wednesday 03rd March 2021 UETCL Hoima Kinubi 33kV Creating h-p tee-off to install dropout fused isolator for direct Hoima Kibati TC, Kalyabuhire kibati t-off and line clearance Kampala West Wednesday 03rd March 2021 Kisugu 11kV and 33kV switchgear Routine Maintenance Kabalagala Kitaranga,Kiwafu,Meya Beach,Kemifa,Nabutiti,Wheeling Zone,Prayer Palace,Wonder world,Comrade bar,Galax FM,Seroma,Mutesasira zone,Internal East Africa University,Shell Kansanga,Elite supermarket,Saida Bumba, Olanya,Kadaga,Diplomatic hotel,Paradiso hotel,Internatiol Hospital Kampala,Kisugu church of Uganda,Zimwe road,Mukwano Apartment,Kabalagala Police station,Diposh bar,Kironde road,General Machinery,Bukasa, parts of Namuwongo, Seebo Green, Bukasa stone quarry,Musisi road,Water tank Hill,Muyenga Umeme mast,Benging Clinic,Muyenga High school, Muyenga chicken tonigt.Heritage International school, Kisugu ,Kibuli,Kikubamutwe,Kibuli mosque,CID Headquarters,Part of Police barracks,Namuwongo publication,Multiple Industry,Sure telecom switching station,Kakungulu Memorial,Kibuli sec sch,Green Hill Academy Kampala West Wednesday 03rd March 2021 Kisugu 11kV and 33kV Take-off MV Cable Inspection,Replacement of rotten structures & jumper Kabalagala Kitaranga,Kiwafu,Meya Beach,Kemifa,Nabutiti,Wheeling Zone,Prayer Palace,Wonder Structures, Lugogo repairs world,Comrade bar,Galax FM,Seroma,Mutesasira