DRC Media Environment Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Unhas Drc Schedule Effect

UNHAS DRC FLIGHT SCHEDULE EFFECTIVE FROM SEPTEMBER 11th 2017 All Planned Flight Times are in LOCAL TIME: Kinshasa, Mbandaka, Brazzaville, Impfondo, Enyelle, Gemena, Libenge, Gbadolite, Zongo, Bangui (UTC + 1); All Other Destinations (UTC + 2) PASSENGERS ARE TO CHECK IN 2 HOURS BEFORE SCHEDULE TIME OF DEPARTURE - PLEASE NOTE THAT THE COUNTER WILL BE CLOSED 1 HOUR BEFORE TIME OF THE DEPARTURE MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY AIRCRAFT DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR DESTINATION DEP ARR KINSHASA MBANDAKA 7:30 9:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA BRAZZAVILLE 7:30 7:45 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA MBANDAKA 7:30 9:00 SPECIAL FLIGHTS SPECIAL FLIGHTS UNO 113H MBANDAKA LIBENGE 9:30 10:30 BRAZZAVILLE MBANDAKA 8:45 10:15 MBANDAKA GBADOLITE 9:30 10:50 DHC8 LIBENGE ZONGO 11:00 11:20 MBANDAKA IMPFONDO 10:45 11:15 GBADOLITE BANGUI 11:20 12:05 5Y-STN ZONGO BANGUI 11:50 12:00 OR IMPFONDO ENYELLE 11:45 12:10 OR BANGUI LIBENGE 13:05 13:25 OR OR BANGUI GBADOLITE 13:00 13:45 ENYELLE MBANDAKA 12:40 13:30 LIBENGE MBANDAKA 13:55 14:55 GBADOLITE MBANDAKA 14:15 15:35 MBANDAKA BRAZZAVILLE 14:00 15:30 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 15:25 16:55 MBANDAKA KINSHASA 16:05 17:35 MAINTENANCE BRAZZAVILLE KINSHASA 16:00 16:15 MAINTENANCE MAINTENANCE MAINTENANCE KINSHASA KANANGA 7:15 9:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA GOMA 7:15 10:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS KINSHASA KANANGA 7:15 9:30 SPECIAL FLIGHTS SPECIAL FLIGHTS UNO 213H KANANGA KALEMIE 10:00 11:05 GOMA KALEMIE 12:15 13:05 KANANGA GOMA 10:00 11:25 EMB-135 KALEMIE GOMA 11:45 12:35 OR KALEMIE -

Phytoplankton Dynamics in the Congo River

Freshwater Biology (2016) doi:10.1111/fwb.12851 Phytoplankton dynamics in the Congo River † † † JEAN-PIERRE DESCY*, ,FRANCßOIS DARCHAMBEAU , THIBAULT LAMBERT , ‡ § † MAYA P. STOYNEVA-GAERTNER , STEVEN BOUILLON AND ALBERTO V. BORGES *Research Unit in Organismal Biology (URBE), University of Namur, Namur, Belgium † Unite d’Oceanographie Chimique, UniversitedeLiege, Liege, Belgium ‡ Department of Botany, University of Sofia St. Kl. Ohridski, Sofia, Bulgaria § Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium SUMMARY 1. We report a dataset of phytoplankton in the Congo River, acquired along a 1700-km stretch in the mainstem during high water (HW, December 2013) and falling water (FW, June 2014). Samples for phytoplankton analysis were collected in the main river, in tributaries and one lake, and various relevant environmental variables were measured. Phytoplankton biomass and composition were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis of chlorophyll a (Chl a) and marker pigments and by microscopy. Primary production measurements were made using the 13C incubation technique. In addition, data are also reported from a 19-month regular sampling (bi-monthly) at a fixed station in the mainstem of the upper Congo (at the city of Kisangani). 2. Chl a concentrations differed between the two periods studied: in the mainstem, they varied À À between 0.07 and 1.77 lgL 1 in HW conditions and between 1.13 and 7.68 lgL 1 in FW conditions. The relative contribution to phytoplankton biomass from tributaries (mostly black waters) and from a few permanent lakes was low, and the main confluences resulted in phytoplankton dilution. Based on marker pigment concentration, green algae (both chlorophytes and streptophytes) dominated in the mainstem in HW, whereas diatoms dominated in FW; cryptophytes and cyanobacteria were more abundant but still relatively low in the FW period, both in the tributaries and in the main channel. -

Actor Heatmap

2017 Q3 Report CONTENTS 1. Results & Overall Progress 2. Sectors 3. Regions 4. Cross-Cutting Sectors, Operations & Management 5. Business Development Services 6. Markets in Crisis 7. Women’s Economic Empowerment INTRODUCTION The third quarter was another busy one at ELAN RDC, as the programme balanced a mid-term evaluation and data verification process in addition to ongoing implementation. A number of new consultants contributed to increased activity for the technical team during the quarter, resulting in concrete workstreams on business development services (BDS), the launch of scoping to replicate existing interventions in conflict-affected Kasai Central, and a renewed focus on gender through increased support from our senior gender adviser. A number of large partnerships were finalised thanks to agreement with DFID on an improved non-objection review process, however, several large partnerships remained delayed due to multiple factors including increasing unstable market conditions. Partnerships in the energy and agriculture sectors were finalised during the quarter, while several partnerships in the financial sector faced delays. The programme has initiated a drive to increase and improve communications of programme results, resulting in an increase in visibility across various media. The launch of the Congo Coffee Atlas, completion of research for The Africa Seed Access Index (TASAI), meeting with mobile network operators to establish a lobbying platform and the finalisation of the contract for a renewable energy marketing campaign are all examples of activities through which ELAN RDC has made more market information available to the broader private sector. More details about third quarter results are found in the following slides. -

IMCK Newsletter 17.3.Pages

INSTITUT MEDICAL CHRETIEN DU KASAI !1 OFINSTITUT MEDICAL!5 CHRETIEN DU KASAI B.P. 205 KANANGA B.P. 205 KANANGA INSTITUT MEDICAL CHRETIENREPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU DUKASAI CONGO REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO Christian Medical Institute Hôpitalof – theEcole d’infirmiers Kasai – Ecole de laborantins - Serving – Service de santé communautairein Central - Service d’ophtalmologie Congo Service dentaire – Centre d’études et de recyclage Hôpital – Ecole d’infirmiers – Ecole de laborantins – Service de santé communautaire - Service d’ophtalmologie E-mail : [email protected] Service dentaire – Centre d’études et de recyclage B. P. 205 Kananga, Republic Democratic du Congo ; Email: [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] 2. Find a way to channel a greater percentage of donations back into that unpopular category 2. Find a way to channel a greater percentage of donations back into that unpopular category of “undesignated” gifts so that we can have the flexibility to apply them where A Periodic Newsletter operational needs are Issuethe most desperate. No. 41 But ifJanuary you cannot (and - thatMarch is understandable, 2017 of “undesignated” gifts so that we can have the flexibility to apply them whereA considering all the news stories one sees about mismanaged funds), then consider operational needs are the most desperate. But if you cannot (and that is understandable, designating gifts carefully to those things that are at the core of IMCK’s operational considering all the news stories one sees about mismanaged funds), then consider The current conflict in the Kasai has needs.I askedFor example the new: Specify IMCK money Administrator, for medicines and Kastin medical Katawa, supplies; Specifyto describe money designating gifts carefully to those things that are at the core of IMCK’s operational added new suffering and danger. -

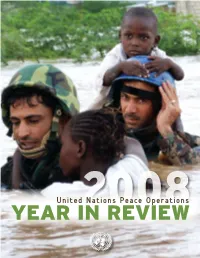

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Introduction Generale

P a g e | 1 INTRODUCTION GENERALE 0.1. Problématique Le présent mémoire porte sur les logotypes et la signification : Analyse de la dénotation et de la connotation des logotypes des banques Trust Merchant Bank (TMB) et Rawbank. En effet, Sperber1 dit qu’il n’y a rien de plus banal que la communication, car les êtres humains sont par nature des êtres communiquant par la parole, le geste, l’écrit, l’habillement et voire le silence, etc. La célèbre école de Palo Alto le dit tout haut aussi: on ne peut pas ne pas communiquer, tout est communication2. La communication, nous la pratiquons tous les jours sans y penser (mais également en y pensant) et généralement avec un succès assez impressionnant, même si parfois nous sommes confrontés à ses limites et à ses échecs. La communication demeure l’élément fondamental et complexe de la vie sociale qui rend possible l’interaction des personnes et dont la caractéristique essentielle est, selon Daniel Lagache3, la réciprocité. Elle est ce par quoi une personne influence une autre et en est influencée, car elle n’est pas indépendante des effets de son action. Morin affirme même que la communication a plusieurs fonctions : l’information, la connaissance, l’explication et la compréhension. Toutefois, pour lui, le problème central dans la communication humaine est celui de la compréhension, car on communique pour comprendre et se comprendre4. Raison pour laquelle, les chercheurs en matière de communication, surtout de notre ère, époque marquée par l’accroissement des entreprises dans la plupart des secteurs de la vie sociale, se trouvent confronté à de nouvelles problématiques qui sont autant d’enjeux pour améliorer la communication. -

Ituri:Stakes, Actors, Dynamics

ITURI STAKES, ACTORS, DYNAMICS FEWER/AIP/APFO/CSVR would like to stress that this report is based on the situation observed and information collected between March and August 2003, mainly in Ituri and Kinshasa. The 'current' situation therefore refers to the circumstances that prevailed as of August 2003, when the mission last visited the Democratic Republic of the Congo. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Swedish International Development Agency. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish Government and its agencies. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the Department for Development Policy, Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Finnish Government and its agencies. Copyright 2003 © Africa Initiative Program (AIP) Africa Peace Forum (APFO) Centre for Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) Forum on Early Warning and Early Response (FEWER) The views expressed by participants in the workshop are not necessarily those held by the workshop organisers and can in no way be take to reflect the views of AIP, APFO, CSVR and FEWER as organisations. 2 List of Acronyms............................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................................................... -

Equateur Province Context

Social Science in Humanitarian Action ka# www.socialscienceinaction.org # # # Key considerations: the context of Équateur Province, DRC This brief summarises key considerations about the context of Équateur Province in relation to the outbreak of Ebola in the DRC, June 2018. Further participatory enquiry should be undertaken with the affected population, but given ongoing transmission, conveying key considerations for the response in Équateur Province has been prioritised. This brief is based on a rapid review of existing published and grey literature, professional ethnographic research in the broader equatorial region of DRC, personal communication with administrative and health officials in the country, and experience of previous Ebola outbreaks. In shaping this brief, informal discussions were held with colleagues from UNICEF, WHO, IFRC and the GOARN Social Science Group, and input was also given by expert advisers from the Institut Pasteur, CNRS-MNHN-Musée de l’Homme Paris, KU Leuven, Social Science Research Council, Paris School of Economics, Institut de Recherche pour le Développment, Réseau Anthropologie des Epidémies Emergentes, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Stellenbosch University, University of Wisconsin, Tufts University, Institute of Development Studies, Anthrologica and others. The brief was developed by Lys Alcayna-Stevens and Juliet Bedford, and is the responsibility of the Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform. Overview • Administrative structure – The DRC is divided into 26 provinces. In 2015, under terms of the 2006 Constitution, the former province of Équateur was divided into five provinces including the new smaller Équateur Province, which retained Mbandaka as its provincial capital.1 The province has a population of 2,543,936 and is governed by the provincial government led by a Governor, Vice Governor, and Provincial Ministers (e.g. -

The DRC Seed Sector

A Quarter-Billion Dollar Industry? The DRC Seed Sector BRIEF DESCRIPTION: Compelling investment opportunities exist for seed companies and seed start-ups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). This document outlines the market potential and consumer demand trends in the DRC and highlights the high potential of seed production in the country. 1 Executive Summary Compelling investment opportunities exist for seed companies and seed start-ups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). This document outlines the market potential and consumer demand trends in the DRC and highlights the high potential of seed production in the country. The DRC is the second largest country in Africa with over 80 million hectares of agricultural land, of which 4 to 7 million hectares are irrigable. Average rainfall varies between 800 mm and 1,800 mm per annum. Bimodal and extended unimodal rainfall patterns allow for two agricultural seasons in approximately 75% of the country. Average relative humidity ranges from 45% to 90% depending on the time of year and location. The market potential for maize, rice and bean seed in the DRC is estimated at $191 million per annum, of which a mere 3% has been exploited. Maize seed sells at $3.1 per kilogramme of hybrid seed and $1.6 per kilogramme of OPV seed, a higher price than in Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and Zambia. Seed-to-grain ratios are comparable with regional benchmarks at 5.5:1 for hybrid maize seed and 5.0:1 for OPV maize seed. The DRC is defined by four relatively distinct sales zones, which broadly coincide with the country’s four principal climate zones. -

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS in DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO (DRC)

Protection of civilians: Human rights violations documented in provinces affected by conflict United Nations Joint Human Rights Office in the DRC (UNJHRO) MONUSCO – OHCHR March 2021 REPORTED HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) Figure 1. Percentage of violations per territory Figure 2. Number of violations per province in DRC SOUTH CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SUDAN North Kivu Tanganyika Bas-Uele Haut-Uele Masisi 79% 21 Kalemie 36% 65 North-Ubangi Beni 64 36 Manono0 100 2 UGANDA CAMEROON South-Ubangi Rutshuru 69 31 Moba0 100 Ituri Mongala Lubero 29 71 77 Nyiragongo 86 14 Maniema Tshopo Walikale 90 10 Kabambare 63% 395 CONGO Equateur North Butembo0 100 Kasongo0 100 Kivu Kibombo0 100 GABON Tshuapa 359 South Kivu RWANDA Kasai Shabunda 82% 18 Mai-Ndombe Kamonia (Kas.)0 100% Kinshasa Uvira 33 67 5 BURUNDI Llebo (Kas.)0 100 Sankuru 15 63 Fizi 33 67 Kasai South Tshikapa (Kas.)0 100 Maniema Kivu Kabare 100 0 Luebo (Kas.)0 100 Kwilu 23 TANZANIA Walungu 29 71 Kananga (Kas. C)0 100 Lomami Bukavu0 100 22 4 Demba (Kas. C)0 100 Kongo 46 Mwenga 67 33 Central Luiza (Kas. C)0 100 Kwango Tanganyika Kalehe0 100 Kasai Dimbelenge (Kas. C)0 100 Central Haut-Lomami Ituri Miabi (Kas. O)0 100 Kasai 0 100 ANGOLA Oriental Irumu 88% 12 Mbuji-Mayi (Kas. O) Haut- Djugu 64 36 Lualaba Bas-Uele Katanga Mambasa 30 70 Buta0 100% Mahagi 100 0 % by armed groups % by State agents The boundaries and names shown and designations ZAMBIA used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 14, No. 6 (G) – August 2002 I counted thirty bodies and bags between the dam and the small rapids, and twelve beyond the rapids. Most corpses were in underwear, and many were beheaded. On the bridges there were still many traces of blood despite attempts to cover them with sand, and on the small maize field to the left of the landing the odors were unbearable. Human Rights Watch interview, Kisangani, June 2002. A Congolese man from Kisangani covers his mouth as he nears the Tshopo bridge, the scene of summary executions by RCD-Goma troops following an attempted mutiny. (c) 2002 AFP WAR CRIMES IN KISANGANI: The Response of Rwandan-backed Rebels to the May 2002 Mutiny 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] August 2002 Vol. 14, No 6 (A) DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO WAR CRIMES IN KISANGANI: The Response of Rwandan-backed Rebels to the May 2002 Mutiny I. SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS......................................................................................................................................3