'Safe Under Us'? the Shrinking of London's Local Countryside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HA16 Rivers and Streams London's Rivers and Streams Resource

HA16 Rivers and Streams Definition All free-flowing watercourses above the tidal limit London’s rivers and streams resource The total length of watercourses (not including those with a tidal influence) are provided in table 1a and 1b. These figures are based on catchment areas and do not include all watercourses or small watercourses such as drainage ditches. Table 1a: Catchment area and length of fresh water rivers and streams in SE London Watercourse name Length (km) Catchment area (km2) Hogsmill 9.9 73 Surbiton stream 6.0 Bonesgate stream 5.0 Horton stream 5.3 Greens lane stream 1.8 Ewel court stream 2.7 Hogsmill stream 0.5 Beverley Brook 14.3 64 Kingsmere stream 3.1 Penponds overflow 1.3 Queensmere stream 2.4 Keswick avenue ditch 1.2 Cannizaro park stream 1.7 Coombe Brook 1 Pyl Brook 5.3 East Pyl Brook 3.9 old pyl ditch 0.7 Merton ditch culvert 4.3 Grand drive ditch 0.5 Wandle 26.7 202 Wimbledon park stream 1.6 Railway ditch 1.1 Summerstown ditch 2.2 Graveney/ Norbury brook 9.5 Figgs marsh ditch 3.6 Bunces ditch 1.2 Pickle ditch 0.9 Morden Hall loop 2.5 Beddington corner branch 0.7 Beddington effluent ditch 1.6 Oily ditch 3.9 Cemetery ditch 2.8 Therapia ditch 0.9 Micham road new culvert 2.1 Station farm ditch 0.7 Ravenbourne 17.4 180 Quaggy (kyd Brook) 5.6 Quaggy hither green 1 Grove park ditch 0.5 Milk street ditch 0.3 Ravensbourne honor oak 1.9 Pool river 5.1 Chaffinch Brook 4.4 Spring Brook 1.6 The Beck 7.8 St James stream 2.8 Nursery stream 3.3 Konstamm ditch 0.4 River Cray 12.6 45 River Shuttle 6.4 Wincham Stream 5.6 Marsh Dykes -

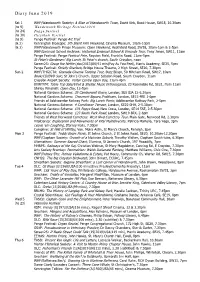

Diary June 2019.Rtf

Diary June 2019 Sat 1 WHF/Wandsworth Society: A Slice of Wandsworth Town, David Kirk, Book House, SW18, 10.30am (to 9) Wandsworth Heritage Festival 2019 (to 24) Penge Festival (to 30) Caterham Festival (to 9) Penge Festival: Penge Art Trail (& 2) Kennington Bioscope: 5th Silent Film Weekend, Cinema Museum, 10am-10pm (& 2) WHF/Wandsworth Prison Museum: Open Weekend, Heathfield Road, SW18, 10am-1pm & 2-5pm WHF/Emanuel School Archives: Historical Emanuel School & Grounds Tour, Tony Jones, SW11, 11am Penge Festival: Penge Festival Fete, Royston Field, Franklin Road, 11am-5pm St Peter's Gardeners' Big Lunch, St Peter's church, South Croydon, noon Screen25: Grasp the Nettle (doc|2013|UK|91 min|Pay As You Feel), Harris Academy, SE25, 5pm Penge Festival: Strictly Sherlock, Bridge House Theatre, 2 High Street, SE20, 7.30pm Sun 2 WHF/THG/CTA: Granada Cinema Tooting Tour, Buzz Bingo, 50 Mitcham Road, SW17, 10am Book/CD/DVD Sale, St John’s Church, Upper Selsdon Road, South Croydon, 11am Croydon Airport Society: Visitor Centre Open Day, 11am-4pm BVWTVM: Table Top Sale/Vinyl & Shellac Music Extravaganza, 23 Rosendale Rd, SE21, from 11am Shirley Windmill: Open Day, 12-5pm National Gardens Scheme: 35 Camberwell Grove, London, SE5 8JA 12-6.30pm National Gardens Scheme: Choumert Square, Peckham, London, SE15 4RE 1-6pm Friends of Addiscombe Railway Park: Big Lunch Picnic, Addiscombe Railway Park, 2-5pm National Gardens Scheme: 4 Cornflower Terrace, London, SE22 0HH, 2-5.30pm National Gardens Scheme: 101 Pepys Road, New Cross, London, SE14 5SE, 2-5.30pm National Gardens Scheme: 123 South Park Road, London, SW19 8RX, 2-6pm Friends of West Norwood Cemetery: West Nwd Cemetery Tour, Main Gate, Norwood Rd, 2.30pm VitalDanza: Exploration and Movements of Vital Multidiversity, Patricia Martello, Tara Yoga, 3pm Leave 'em Laughing, Stanley Halls, 7.30pm Compline: St Hild of Whitby, Ven. -

The Constitution

Public Document Pack 1 THE CONSTITUTION WOKING BOROUGH COUNCIL Contents Pages Pages 3 - 4 Part 1 - Introduction Pages 5 - 8 Part 2 - Articles of the Constitution Pages 9 - 46 Part 3 - Responsibility for Functions, Management Arrangements and Scheme of Delegations Pages 47 - 120 Part 4 - Council Procedure Rules Pages 121 - 182 Part 5 - Codes and Protocols Pages 183 - 294 Index Pages 295 – 318 2 Agenda Item 1 3 CONTENTS Part 1 – Introduction 5 Introduction 7 Part 2 – Articles of the Constitution 9 Article 1 – The Constitution 11 Article 2 – Members of the Council 13 Article 3 – Citizens and The Council 15 Article 4 – The Full Council 17 Article 5 – Chairing The Council 19 Article 6 – Overview and Scrutiny Committee 21 Article 7 – The Leader 25 Article 8 – The Executive 27 Article 9 – Regulatory and Other Committees 29 Article 10 – The Standards and Audit Committee 31 Article 11 – Officers 33 Article 12 – Decision Making 37 Article 13 – Finance and Contracts 39 Article 14 – Review and Revision of the Constitution 41 Article 15 – Suspension, Interpretation and Publication of the Constitution 43 Schedule 1 – Description of Executive Arrangements 45 Part 3 – Responsibility for Functions, Management Arrangements and Scheme of Delegations 47 Functions 49 Joint Committee for the Oversight of Delivery of Surrey Public Authority Services (“Surrey First”) 55 Woking Joint Committee 59 Joint Waste Collection Services Committee 81 Management Arrangements 89 Scheme of Delegations 91 Part 4 – Council Procedure Rules 121 Standing Orders 123 Conventions -

Date Plant Collector Locality Vc Inst 1868 5 0 Primula Polyantha Crespigny, E

natstand: last updated 14/12/2014 URL: www.natstand.org.uk/pdf/DeCrespignyEC002.pdf Person: De Crespigny, Eyre N. Champion (1821 – 1895) Description: Chronologically arranged list of specimens From various British herbaris. Source: Herbaria @ Home and University of Hull Extraction date: 2014 December 13 Annotated by: Richard Middleton Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Date Plant Collector Locality vc Inst 1868 5 0 Primula polyantha Crespigny, E. de Normandy, France HLU 1869 0 0 Teucrium scordium Crespigny, E. de Braunton Burrows 4 MANCH 1870 7 0 Oenanthe fluviatilis Crespigny, E. de River Lee, Edmonton 21 HLU 1871 0 0 Ranunculus arvensis Crespigny, E. de 21 MANCH 1871 0 0 Ranunculus arvensis Crespigny, E. de 21 MANCH 1871 0 0 Potamogeton friesii Crespigny, E. de Tottenham,Lea Canal 21 MANCH 1872 0 0 Galium tricornutum Crespigny, E. de Croydon 17 MANCH 1872 0 0 Potamogeton crispus Crespigny, E. de Tottenham 21 MANCH 1872 0 0 Potamogeton lucens Crespigny, E. de Tottenham,Lea Canal 21 MANCH 1873 0 0 Schoenoplectus x carinatus Crespigny, E. de Mortlake 17 MANCH 1873 0 0 Anemone nemorosa Crespigny, E. de Hampstead Heath 21 MANCH 1873 0 0 Anemone nemorosa Crespigny, E. de Pinner 21 MANCH 1874 0 0 Potamogeton berchtoldii Crespigny, E. de Woolwich 16 MANCH 1874 0 0 Campanula trachelium Crespigny, E. de Merstham 17 SLBI 1874 0 0 Dianthus deltoides Crespigny, E. de Thames Ditton 17 MANCH 1874 0 0 Carex pallescens Crespigny, E. de Pinner 21 MANCH 1874 0 0 Cochlearia anglica Crespigny, E. de Banks of the Thames, 16 HLU Woolwich, London 1874 6 0 Carex vesicaria Crespigny, E. -

EXE20-001 Appendix 4A

Appendix 4a WOKING BOROUGH COUNCIL FOOD SAFETY SERVICE PLAN 2020/2021 1. Service Aims and Objectives 1.1. Aims and Objectives 1.1.1. The objectives of the food safety service are: to ensure that food and drink intended for sale for human consumption, which is produced, stored, distributed, handled or consumed within the Borough is without risk to the health or safety of the consumer; to investigate suspected and confirmed food poisoning incidents, to locate the source of contamination and to prevent it spreading to protect the health of the public; to provide information and advice on food safety matters for business and members of the public. 1.2. Links to Corporate Objectives and Plans 1.2.1. This food safety service plan is the Council’s expression of its commitment to the delivery of a continually improving food service, in line with the corporate vision and values to provide excellent services in a forward thinking and sustainable way. 1.2.2. Food safety, and specifically the improvement of compliance with food hygiene regulations by businesses in the Borough is outlined as a Corporate Objective within Woking Borough Council’s Service Plans for 2020/21. 1.2.3. The food safety service contributes to the Council’s priority of promoting health and well being, healthy diet is also one of the 6 priorities agreed by the Woking Health and Wellbeing Board. 1.2.4. This plan provides information about the food safety services, the means by which they are provided and the means for monitoring and reviewing service performance against set standards. -

North Hertfordshire Green Belt Review

99 North Hertfordshire Green Belt Review July 2016 North Hertfordshire Local Plan 2011 - 2031 Evidence Base Report North Hertfordshire Green Belt Review July 2016 2 North Hertfordshire Green Belt Review July 2016 Contents 1. Background and Approach to the Review…………………………………. 5 PART ONE: ASSESSMENT OF THE CURRENT GREEN BELT, VILLAGES IN THE GREEN BELT AND POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITES IN THE GREEN BELT 2. Strategic Review of the Green Belt…………………………………...………….. 9 2.1 Background to Review 2.2 Role and purpose of Green Belt 2.3 The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) 2.4 Methodology 2.5 Assessment - existing Green Belt 2.6 Checking the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas 2.7 Preventing neighbouring towns merging into one another 2.8 Safeguarding the countryside from encroachment 2.9 Preserving the setting and special character of Historic Towns 2.10 Overall contribution to Green Belt purposes 3. Refined Review of the Green Belt……………………………………………..…. 33 4. Analysis of Villages in the Green Belt…………………………………………... 67 4.1 Purpose and Method of Appraisal 4.2 NHDC Proposed Policy Context 4.3 Analysis of Contribution to the Green Belt 5. Analysis of Potential Development Sites in the Green Belt…………………. 99 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Methodology - potential development sites 5.3 Assessment of Potential Development Sites PART TWO: ASSESSMENT OF POTENTIAL ADDITIONS TO THE GREEN BELT 6. Assessment of Countryside beyond the Green Belt………………………….. 135 6.1 Introduction 6.2 Role and purpose of Green Belt 6.3 Methodology – potential Green Belt areas -

Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening of Woking Borough Council's Draft Core Strategy Policies with Potential for Impacts on Natura 2000 and Ramsar Sites

HABITATS REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT SCREENING OF WOKING BOROUGH COUNCIL'S DRAFT CORE STRATEGY POLICIES WITH POTENTIAL FOR IMPACTS ON NATURA 2000 AND RAMSAR SITES WOKING BOROUGH COUNCIL HRA SCREENING REPORT December 2011 HABITATS REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT SCREENING OF WOKING BOROUGH COUNCIL'S DRAFT CORE STRATEGY POLICIES WITH POTENTIAL FOR IMPACTS ON NATURA 2000 AND RAMSAR SITES WOKING BOROUGH COUNCIL HRA SCREENING REPORT December 2011 Project Code: WBCSAC11B.9 Prepared by: Andrea Hughes – Mayer Brown/Chris Stapleton – Environmental Planner/Derek Finnie - Bioscan Issue Date: December 2011 . Status: FINAL Rev 4 Mayer Brown Limited, Lion House, Oriental Road, Wok ing, Surrey GU22 8AP Telephone 01483 750508 Fax 01483 767113 [email protected] www.MayerBrown.co.uk HABITATS REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT SCREENING OF WOKING BOROUGH COUNCIL'S DRAFT CORE STRATEGY POLICIES WITH POTENTIAL FOR IMPACTS ON NATURA 2000 AND RAMSAR HRA SCREENING REPORT HABITATS REGULATIONS ASSESSMENT SCREENING OF WOKING BOROUGH COUNCIL'S DRAFT CORE STRATEGY POLICIES WITH POTENTIAL FOR IMPACTS ON NATURA 2000 AND RAMSAR SITES HRA SCREENING REPORT Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 2. BASELINE CONDITIONS ................................................................................................. 8 3. EVALUATION METHODOLOGY – PHASE I .................................................................. 24 4. SCREENING .................................................................................................................. -

Woking Borough Council Health and Safety Service Plan 2019/2020

Appendix 4b WOKING BOROUGH COUNCIL HEALTH AND SAFETY SERVICE PLAN 2019/2020 1. Service Aims and Objectives 1.1. Aims and Objectives 1.1.1. The objectives of the health and safety service are: to meet the Council’s statutory responsibilities to ensure that working environments are safe and without risks to health or welfare, and that work activities do not have an adverse effect on the public. to investigate all complaints about health and safety standards and notifications of accidents, occupational ill-health and dangerous occurrences, in premises for which the Council is the enforcing authority i.e. retail, leisure, service sector. 1.2. Links to Corporate Objectives and Plans 1.2.1. This service plan is the Council’s expression of its commitment to the delivery of a continually improving health and safety service, in line with the corporate vision and values to provide excellent services in a forward thinking and sustainable way. 1.2.2. The health and safety service contributes to the Council’s priority of promoting health and overall well being, the six health priorities agreed by the Woking Health & Wellbeing Board and to the Community Strategy priorities of improving access to information on improving health and preventing illness. The health and safety service also seeks to develop and promote links with the local business community, to improve standards of health and safety management, which in turn has a positive impact on business productivity. 1.2.3. This plan provides information about the health and safety services provided, the means by which they are provided and the means for monitoring and reviewing service performance against set standards. -

Hankinson Duckett Associates

WOODHAM LANE LANDSCAPE ASSESSMENT AND GREEN BELT REVIEW for Woking Borough Council by Hankinson Duckett Associates HDA ref: 719.2/v3 August 2016 hankinson duckett associates t 01491 838175 e [email protected] w www.hda-enviro.co.uk The Stables, Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, OX10 8BA Hankinson Duckett Associates Limited Registered in England & Wales 3462810 Registered Office: The Stables, Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Wallingford, OX10 8BA Contents Page 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................... 1 2 The Local Area ................................................................................................................ 1 2.1 Description of the Local Area ............................................................................................ 1 2.2 Landform and Drainage .................................................................................................... 1 2.3 Land Use and Vegetation ................................................................................................. 2 2.4 Landscape Character ........................................................................................................ 3 2.5 Designations ..................................................................................................................... 5 3 Green Belt ....................................................................................................................... -

Buses from Locksbottom

Buses from Locksbottom Catford and Catford Bridge 336 261 Lewisham Brookehowse Community Centre for Bellingham Lee Green 61 Hail & Ride Lee Chislehurst Brookehowse Road section Gordon Arms Whitefoot Lane CHISLEHURST Grove Park Hail & Ride Chislehurst R4 Downham section War Memorial Paul’s Cray Hill Health Centre Burnt Ash Lane Augustine Road Hail & Ride section Crystal Palace Parade Rangefield Road St Paul’s 358 Crystal Palace 61 Cray Road for National Sports Centre Amherst Drive St Mary Cray Plaistow Green Bromley North High Street Anerley Hail & Ride ST MARY CRAY Chislehurst section Penge Pawleyne Arms Road Shortlands BROMLEY Poverest Road Hail & Ride Beckenham Road R2 section PETTS WOOD Cockmannings Clock House Bromley Park Langley The Glades Petts Wood Poverest Road Kent Road Lower Road Road Cray Valley Road Cray Avenue Royal Albert Beckenham Chinese Garage Coppice Estate War Memorial Eden Park Bromley South Whitebeam Avenue Ramsden Estate BECKENHAM Rye Crescent Elmers End Homesdale Hail & Ride Road Bickley section 353 Green Bromley Common Southlands Grove Perry Hall Road Ramsden Estate Crown Shepperton Road Petten Grove Southborough Library Orpington Orpington Carlton Parade Walnuts Centre Turpington Lane Crofton Lane (Homefield Rise) ORPINGTON Crofton Road HAYES Bromley Common Orpington Addington Holy Trinity Church Village Coney Hall Bromley Interchange Addington Road Hayes A P A Bus Garage E V 353 E R U K N N E U Tubbenden Lane Orpington V E 358 A Route does not serve the K Orpington Walnuts Centre R HN Hail & Ride 358 A Walnuts -

20/00984/Adj

Committee Date 14.07.2020 Former Broke Hill Golf Course Address Sevenoaks Road Halstead Sevenoaks Kent TN14 7HR Application 20/00984/ADJ Officer: Suzanne Lyon number Ward Adjacent Local Authority Proposal Outline application for residential development of up to 800 dwellings, incl. affordable housing units and self-build plots; retirement care community for up to 180 C2 units; primary school hub with associated sports facilities/outdoor space; sports hub incl. rugby and hockey pitches with separate car park and clubhouse areas; 2 ha of commercial B1 use; local centre incl. commercial, retail & community facilities and undercroft car parking for Knockholt station; country park/ open space incl. landscaping, infrastructure & groundworks; with all matters reserved except for access Applicant Agent Quinn Estates Montagu Evans LLP Reason for Previous Case went to DC Councillor call in referral to Committee No committee RECOMMENDATION Raise Objection 1 SUMMARY OF KEY REASONS FOR RECOMMENDATION The location and scale of the proposed development undermines the purposes of the Green Belt. The proposed development would have the potential to add significant pressure to existing medical practitioner facilities within Bromley. The proposal is likely to result in a number of impacts on transport services and local roads in Bromley. 2 LOCATION 2.1 The site is located on the southern side of Sevenoaks Road and comprises the Broke Hill Golf Course. The site is located within the Metropolitan Green Belt 3 PROPOSAL 3.1 Outline application for residential development of up to 800 dwellings, incl. affordable housing units and self-build plots; a retirement care community for up to 180 C2 units; primary school hub with associated sports facilities/outdoor space; sports hub incl. -

Epsom and Ewell Green Belt Study Stage Two

Epsom and Ewell Green Belt Study | May 2018 Epsom and Ewell Green Belt Study Stage Two Epsom and Ewell Borough Council May 2018 1 Epsom and Ewell Green Belt Study | May 2018 Chapter 1. Introduction 1 3. Scope and Methodology 7 1.1. Background 1 3.1. Methodology 7 1.2. Requirement for the Green Belt Study 4. Sites 9 Stage Two 1 4.1. Assessed Parcels 10 2. Policy Context 3 5. Assessment 13 2.1. National Planning Policy Framework 3 6. Conclusions 73 2.2. Draft Revised National Planning 7. Next Steps 74 Policy Framework 3 Appendix A. Workshop Invitees 77 2.3. Epsom and Ewell Local Plan 4 Appendix B. Definitions 79 2 Epsom and Ewell Green Belt Study | May 2018 1 Introduction Atkins Limited has been commissioned by Epsom and Ewell Borough Council (EEBC) to carry out a Green Belt Study Stage Two. This Stage Two Study (GBS Stage Two) assesses the promoted or lower performing Green Belt parcels, considers constraints and identifies parcels which are potentially suitable for release from the Green Belt which could potentially contribute to EEBC’s housing land supply as part of the current Core Strategy Review. This Study will be used to inform decisions relating to identified long term growth requirements for the borough and discussions with neighbouring authorities under the Duty to Co-operate relating to the accommodation of wider growth pressures from beyond the authority boundary. 1.1 Background 1.2 Requirement for In 2016, Atkins Limited was commissioned by EEBC to carry the Study Stage Two out a strategic assessment of the Metropolitan Green Belt The key driver for this GBS Stage Two is EEBC’s need to within the borough (the Green Belt Stage One Study).