Naaman's Healing and Gehazi's Affliction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

179-Naaman, Elisha, and Gehazi

EPISODE NO. 179 2 Kings 5:1-27 Naaman Was Cured of Leprosy 1 Naaman was the general over the army of the king of Syria. To his master, Naaman was a great man. He had much honor because Yahweh had used him to give victory to Syria. Naaman was a strong warrior. However, Naaman had leprosy. 2 The Syrians used to go out to raid the Israelites. In so doing, they captured a little girl from the land of Israel. She became a servant girl to Naaman’s wife. 3 She said to her owner, “I wish that my master would meet the prophet who lives in Samaria! Then he would heal the skin disease of Naaman!” 4 So, Naaman went to the king of Syria, and Naaman told him what the Israelite girl had said. 5 The king of Syria said, “Go on; enter the land of Israel. I will send a letter to the king of Israel.” So, Naaman left on the trip. And, for gifts, he took with him about 750 pounds of silver. He also took along with him about 150 pounds of gold as a gift, and 10 sets of clothes. 6 Naaman brought the official letter to the king of Israel. It read: “Listen, I am hereby sending my servant Naaman to you with this letter, so that YOU can heal him of his skin disease!” 7 After the king of Israel read the letter, he ripped his clothes. He said, “I am NOT the one true God! I cannot give life or take it away! Why does this man send someone with such a bad skin disease for ME to heal!? You can see that the king of Syria is trying to pick a fight with me!” 8 Elisha, the man of the one true God, heard that the king of Israel had ripped his clothes. -

February 3, 2021

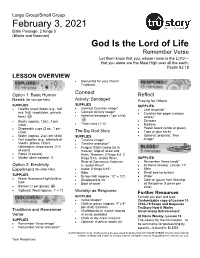

Large Group/Small Group February 3, 2021 Bible Passage: 2 Kings 5 (Elisha and Naaman) God Is the Lord of Life Remember Verse Let them know that you, whose name is the LORD— that you alone are the Most High over all the earth. Psalm 83:18 LESSON OVERVIEW Mementos for your church Traditions Connect Option 1: Basic Human Reflect (for younger kids) Activity: Bandaged Needs Praying for Others SUPPLIES SUPPLIES SUPPLIES Connect Question image* Healthy snack foods (e.g., trail Leaf template* Connect Activity image* mix, fruit, vegetables, granola Construction paper (various bars) Adhesive bandages (1 per child) colors) Bowls (approx. 12oz.; 1 per Scissors child) Trash cans (1–3) Markers Disposable cups (2 oz.; 1 per Poster board (white or green) child) The Big God Story Tape or glue sticks Water (approx. 2 oz. per child) SUPPLIES Optional: projector, Tree Fort supplies (e.g., blankets or Timeline image* image* sheets, pillows, chairs, Timeline animation* clothespins, large boxes; 2–3 Images: Elijah Going Up to of each) Heaven, Map of Israel and Paper (3 sheets) Aram, Naaman, 2 Kings 5:8, 2 Marker (dark-colored, 1) Kings 5:10, Jordan River, SUPPLIES River of Damascus, Naaman Remember Verse cards* Option 2: Electricity in Jordan River* At Home Weekly: Lesson 11* Experiment (for older kids) Audio: 2 Kings 5:15* Bible Bible Small bowl or bucket SUPPLIES Scrap cloth (approx. 12'' x 12'') Water Warm fluorescent light bulb or Disappearing ink Cloth or gauze from Worship tube Bowl of water as Response (1 piece per Balloon (1 per group) child) Optional: Wool (approx. -

The Healing of Naaman in Missiological Perspective Walter A

Volume 61: Number 3 July 1997 Table of Contents Eschatological Tension and Existential Angst: "Now" and "Not Yet" in Romans 214-25 and lQSll (Community Rule, Manual of Discipline) Lane A. Burgland ........................... 163 The Healing of Naaman in Missiological Perspective Walter A. Maier I11 .......................... 177 A Chapel Sermon on Exodus 20:l-17 JamesG. Bollhagen ......................... 197 Communicating the Gospel Without Theological Jargon Andrew Steinman .......................... 201 Book Reviews .................................... 215 Salvation in Christ: A Lutheran-Orthodox Dialogue. Edited with an Introduction by John Meyendorff and Robert Tobias .......................Ulrich Asendorf A History of the Bible as Literature. By David Norton. ................................ Cameron A. MacKenzie Ministry in the NmTestament. By David L. Bartlett .................................... Thomas M. Winger The Justificationof the Gentiles: Paul's Letters to the Galatians and Romans. By Hendrikus Boers ........Charles A. Gieschen Christianity and Christendom in the Middle Ages: The Relations Between Religion, Church, and Society. By Adriaan H. Bredero ...................Karl F. Fabrizius The Myste y and the Passion: A Homiletic Reading of the Gospel Traditions. By David G. Buttrick ...... Carl C. Fickenscher I1 Christ in Christian Tradition. By Aloys Grillrneier with Theresia Hainthaler ................. William C. Weinrich Theological Ethics of the New Testament. By Eduard Lohse ...................................H. Armin Moellering Paul's Narrative Thought World:The Tapestry of Tragedy and Triumph. By Ben Witherington .........Charles A. Gieschen Galileo, Bellarmine, and the Bible. By Richard J.Blackwell. ................................Cameron A. MacKenzie Teaching Law and Gospel. By William Fischer ... Erik J. Rottmann Books Received. .................................. 238 The Healing of Naaman in Missiological Perspective Walter A. Maier I11 This study analyzes the narrative of the healing of Naaman the Syrian, 2 Kings 53-19a. -

Resurrection Or Miraculous Cures? the Elijah and Elisha Narrative Against Its Ancient Near Eastern Background

Bar, “Resurrection or Miraculous Cures?” OTE 24/1 (2011): 9-18 9 Resurrection or Miraculous Cures? The Elijah and Elisha Narrative Against its Ancient Near Eastern Background SHAUL BAR (UNIVERSITY OF MEMPHIS) ABSTRACT The Elijah and Elisha cycles have similar stories where the prophet brings a dead child back to life. In addition, in the Elisha story, a corpse is thrown into the prophet’s grave; when it comes into con- tact with one of his bones, the man returns to life. Thus the question is do these stories allude to resurrection, or “only” miraculous cures? What was the purpose of the inclusion of these stories and what message did they convey? In this paper we will show that these are legends that were intended to lend greater credence to prophetic activity and to indicate the Lord’s power over death. A INTRODUCTION There is consensus among scholars that Dan 12:2-3, which they assign to the 1 second century B.C.E., refers to the resurrection of the dead. The question be- comes whether biblical texts earlier than this era allude to this doctrine. The phrase “resurrection of the dead” never appears in the Bible. Scholars searching for biblical allusions to resurrection have cited various idioms.2 They list verbs including “arise,”3 “wake up,”4 and “live,”5 all of which can denote a return to life. We also find “take,”6 which refers to being taken to Heaven, the noun “life,”7 and “see.”8 In the present paper however, we shall examine the stories of the Elijah and Elisha cycles which include similar tales in which the prophet brings a dead child back to life: in Elijah’s case, the son of the widow of Zare- phath (1 Kgs 17:17-24); in Elisha’s, the son of the Shunammite matron (2 Kgs 4:31-37). -

“It Doesn't Make Sense.”

“It Doesn’t Make Sense.” Presented by Rev. Kristen Lowe on 7/1/2018 At Crossroads United Methodist Church Waunakee, WI Scripture: Philippians 4:6-7 Do not be anxious about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known to God. And the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus. 2 Kings 5:13-14 But his officers tried to reason with him and said, “If the prophet had told you to do some great thing, wouldn’t you have done it? So you should certainly obey him when he says simply to go and wash and be cured!” So Naaman went down to the Jordan River and dipped himself seven times, as the prophet had told him to. And his flesh became as healthy as a little child’s, and he was healed! Jeremiah 17:7-8 “But blessed is the one who trusts in the Lord, whose confidence is in him. They will be like a tree planted by the water that sends out its roots by the stream. It does not fear when heat comes; its leaves are always green. It has no worries in a year of drought and never fails to bear fruit.” Today I want to take a very in depth look at our friend Naaman from 2 Kings as we listen to how naaman’s story impacts our story. Lurene shared a a few verses of the story where we find Naaman following Elisha the prophets advice by dunking himself 7 times in the Jordan and becoming cured. -

The Perfect Priest: an Examination of Leviticus 21:17-23 Jared Wilson George Fox University

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Seminary Masters Theses Seminary 1-1-2013 The perfect priest: an examination of Leviticus 21:17-23 Jared Wilson George Fox University This research is a product of the Master of Arts in Theological Studies (MATS) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Wilson, Jared, "The perfect priest: an examination of Leviticus 21:17-23" (2013). Seminary Masters Theses. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/seminary_masters/7 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seminary Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY THE PERFECT PRIEST- AN EXAMINATION OF LEVITICUS 21:17-23 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GEORGE FOX EVANGELICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (THEOLOGICAL STUDIES) BY JARED WILSON PORTLAND, OREGON FEBRUARY 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Jared Wilson All rights reserved To Courtney, Jeremiah, Micah, Jedidiah, and Adley Contents Preface....................................................................................................................................... iv Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... vi Chapter One ............................................................................................................................. -

Bereans Online Enews B"H Parashat Metzora - 'Leper' (Leviticus 14:1-15:33)

Bereans Online eNews http://www.bereansonline.org B"H Parashat Metzora - 'Leper' (Leviticus 14:1-15:33) The name 'Metzora', the second portion for this week, comes from the second verse of Leviticus 14: Vayedaber HaShem el-Moshe lemor. zot tihye torat ha-metzora b'yom tahorato v'huva el-ha-kohen Then HaShem spoke to Moses, saying, "This shall be the law of the leper for the day of his cleansing: He shall be brought to the priest." Leviticus 14:1-2 Previously, in Parashat Tazria we are given some detailed instructions regarding what our English BiBles call "a leper." Continuing in Parashat Metzora, the topic of "leprosy" continues. If you ever hope to unravel these passages, and the passages in the Gospel accounts you must learn to look Beyond this English word. The people in Scripture who are afflicted with tza'arat do not have "Hanson's Disease" or what is known as "leprosy" In fact, if one examines the use of this HeBrew word in Scripture you will find that it is not even a physical disease in the normal sense. Yes, it has physical attriButes, which make it appear that the person who is afflicted is a "dead man walking" - But it is not the disease that is Being addressed in these passages. A common misunderstanding of those reading these passages (and the Gospels) is that the person with tza'arat has a communicable disease, and hence G-d is mandating Quarantine for medical reasons. Nothing could Be further from the truth. We read in last week's parasha that a priest was to examine a person who suspected they had tza'arat, and determine if the person had tza'arat or not [were "unclean" or not]. -

Jesus, Elisha, and Moses: a Study in Typology

Running head: JESUS, ELISHA, AND MOSES 1 Jesus, Elisha, and Moses: A Study in Typology Jeremy Tetreau A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2018 JESUS, ELISHA, AND MOSES 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Donald Fowler, Th.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Harvey Hartman, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Mark Harris, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Cindy Goodrich, Ed.D., M.S.N., R.N., C.N.E. Assistant Honors Director ______________________________ Date JESUS, ELISHA, AND MOSES 3 Abstract Because the Evangelists wrote with the intention of communicating specific, theological truths to their readers, the details they include in their gospels are important. Further, one way the story of the Bible unfolds and is theologically interpreted is through the use of repetition and typology. A number of the miracle accounts of Elisha are analogous to Jesus’ own miracles as recorded in the gospels. Because of this, it is likely that the Evangelists are inviting readers to understand Jesus in light of Old Testament prophets and events, specifically as the appearance of a Prophet-like-Moses. A Jesus-Elisha typology, then, must be understood as only one strand of this more intricate prophetic typology. JESUS, ELISHA, AND MOSES 4 Jesus, Elisha, and Moses Introduction The writers of the four canonical gospels were not mere biographers; they were theologians. They were propagandists in the best possible way. They were the Evangelists, tasked with the sacred privilege of faithfully compiling eyewitness testimony and portraying Jesus “as these eyewitnesses portrayed him,” giving that testimony “a permanent literary vehicle.”1 Luke informs us that his gospel was written “so that you may know the exact truth about the things you [Theophilus] have been taught” (Lk. -

Luke 4:14 – 30

Luke 4:14 – 30 4:14 And Jesus returned to Galilee in the power of the Spirit, and news about him spread through all the surrounding district. 15 And he began teaching in their synagogues and was praised by all. 16 And he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up; and as was his custom, he entered the synagogue on the Sabbath, and stood up to read. 17 And the book of the prophet Isaiah was handed to him. And he opened the book and found the place where it was written, 18 ‘The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives, and recovery of sight to the blind, to set free those who are oppressed, 19 to proclaim the favorable year of the Lord.’ 20 And he closed the book, gave it back to the attendant and sat down; and the eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. 21 And he began to say to them, ‘Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.’ 22 And all were speaking well of him, and wondering at the gracious words which were falling from his lips; and they were saying, ‘Is this not Joseph’s son?’ 23 And he said to them, ‘No doubt you will quote this proverb to me, ‘Physician, heal yourself! Whatever we heard was done at Capernaum, do here in your hometown as well.’’ 24 And he said, ‘Truly I say to you, no prophet is welcome in his hometown. -

2 Chronicles

YOU CAN UNDERSTAND THE BIBLE 2 Chronicles BOB UTLEY PROFESSOR OF HERMENEUTICS (BIBLE INTERPRETATION) STUDY GUIDE COMMENTARY SERIES OLD TESTAMENT VOL. 7B BIBLE LESSONS INTERNATIONAL MARSHALL, TEXAS 2017 INTRODUCTION TO 1 AND 2 CHRONICLES I. NAME OF THE BOOK A. The name of the book in Hebrew is “the words (events) of the days (years).” This is used in the sense of “a chronicle of the years.” These same words occur in the title of several books mentioned as written sources in 1 Kings 14:19,29; 15:7,23,31; 16:5,14,20,27; 22:46. The phrase itself is used over thirty times in 1 and 2 Kings and is usually translated “chronicles.” B. The LXX entitled it “the things omitted (concerning the Kings of Judah).” This implies that Chronicles is to Samuel and Kings what the Gospel of John is to the Synoptic Gospels. See How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, by Gordon Fee and Douglas Stuart, pp. 127-148. As the Gospel writers under inspiration (see Special Topic: Inspiration) had the right to select, adapt, and arrange the life of Jesus (not invent actions or words), so too, the inspired authors of OT narratives (see Expository Hermeneutics: An Introduction, by Elliott E. Johnson, p. 169). This selection, adaptation, and chronological/thematic arrangement of words/events was to convey theological truth. History is used as a servant of theology. Chronicles has suffered, much as the Gospel of Mark did. They were both seen as “Readers Digest” summaries and not “a full history.” This is unfortunate! Both have an inspired message. -

Teacher Bible Study Lesson Overview/Schedule

1st-3rd Grade Kids Bible Study Guide Unit 13, Session 4: Elisha and Naaman TEACHER BIBLE STUDY Everyone seems to get sick at some point in his or her lifetime … most often many, many times! Illness is probably no stranger to the kids you teach. In today’s Bible story, Naaman—a commander for the Syrian army—was really sick. He had leprosy, a skin disease that was likely disfiguring and isolating. Without a cure, Naaman would face great suffering. But help came from an unlikely source: a young slave girl. The people of Israel and Syria were often at odds with one another. The Syrians sometimes attacked the cities in Israel and plundered them. They took what they wanted, including people to work as slaves. The young slave girl who served Naaman’s wife had been taken from her home in Israel. As an Israelite, the girl knew about the one true God. She was familiar with God’s prophets, including Elisha, who had performed miracles to help and heal people. The girl told her mistress that Elisha the prophet could heal Naaman. So the king of Syria sent a letter to the king of Israel, asking him to cure Naaman of his leprosy. But the king of Israel had no power to heal Naaman. The power to heal comes only from God. Elisha called for Naaman. But what happened next was not at all what Naaman expected. Naaman expected Elisha to call upon the name of God, wave his hand over Naaman, and miraculously heal him. Instead, Elisha instructed Naaman to go wash in the river. -

River out of Eden: Water, Ecology, and the Jordan River in the Jewish

RIVER OUT OF EDEN: WATER, ECOLOGY, AND THE JORDAN RIVER IN THE JEWISH TRADITION ECOPEACE / FRIENDS OF THE EARTH MIDDLE EAST (FOEME) SECOND EDITION, JUNE 2014 I saw trees in great profusion on both banks of the stream. This water runs out to the eastern region and flows into the Arabah; and when it comes into the Dead Sea, the water will become wholesome. Every living creature that swarms will be able to live wherever this stream goes; the fish will be very abundant once these waters have reached here. It will be wholesome, and © Jos Van Wunnik everything will live wherever this stream goes. Ezekiel 47:7-9 COVENANT FOR THE JORDAN RIVER We recognize that the Jordan River Valley is a that cripples the growth of an economy landscape of outstanding ecological and cultural based on tourism, and that exacerbates the importance. It connects the eco-systems of political conflicts that divide this region. It Africa and Asia, forms a sanctuary for wild also exemplifies a wider failure to serve as plants and animals, and has witnessed some of custodians of the planet: if we cannot protect a the most significant advances in human history. place of such exceptional value, what part of the The first people ever to leave Africa walked earth will we hand on intact to our children? through this valley and drank from its springs. Farming developed on these plains, and in We have a different vision of this valley: a vision Jericho we see the origins of urban civilization in which a clean, living river flows from the Sea itself.